Holy Places

by Dr. Cora Angier Sowa

This essay was originally published in New York Affairs 4:3 (Summer/Fall 1977). It was thus being written at the same time as the construction of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center. The focus of my writing was Pennsylvania Station, a monumental landmark trashed, sadly, by our own civilization. The WTC was--and is--another mythic landmark of many interlocking meanings, but it was born too late for inclusion in this article. Some of its meanings could not have been forseen, for they were added to its other significance by the tragic destruction of its spectacular structures. An epilogue on the Towers, "alas, too young taken from us," has now been added. (Click on "Epilogue" to go directly to this page.)

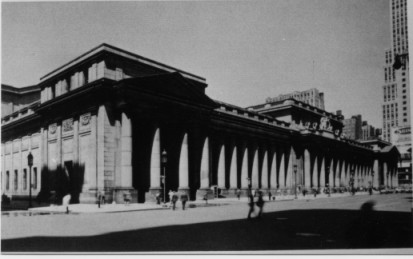

Pennsylvania Station: a monument of splendid grandeur and the location of many pilgrimages

A landmark is not just a pretty building or an old one. Important buildings orient us psychologically as well as physically and are intimately bound up with the spirit of the city.

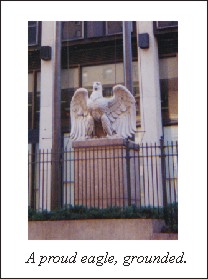

The eagles are all that's left of Pennsylvania Station. They

stand in

front of Madison Square Garden, which replaced it, together with

the statue of

a long-gone president of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the wrong

president at that--it

was Alexander Cassatt, not Samuel Rea, whom architect

Charles McKim talked into creating New York's magnificent evocation of

ancient Rome.

Now there are only the two eagles, proud birds unceremoniously

grounded, in

landscaped planters amid the crowds. To the preservationist, who

can never look

at those blocks along Seventh Avenue without seeing another,

solider, lovelier

building superimposed on the tacky shopping-center architecture

of the present

structure, the humbled survival of the eagles is an empty

gesture, for Penn

Station should never have been destroyed. To a developer, who

thinks all old

buildings should be torn down in the name of progress, they are a

sop to sentimentality. But to the mythologist, searching for signs of

meaning

among the agonies of reality, it is something else--the continuity of a

Holy Place. A gathering

place for people once, it is still a public gathering place; with

the move from

old building to new building, the protectors of the place have,

as in ancient days,

been brought along--the Lares and Penates.

Mythic guardians in an American city? Modern people in general, and Americans in particular, aren't usually credited with having a sense of the sacred. We pollute our rivers because we no longer see them as kindly gods with human faces; we bulldoze acres of noble trees because they are seen not as habitations of wood nymphs, but as commercially developable property. Our only concession to the continuity of a historic building may be a bronze plaque on the wall of the high-rise that now occupies the site. "Manhattan" and "Brooklyn" are goddesses only in the statues from the Manhattan Bridge that now flank the entrance to the Brooklyn Museum. But that word "only" may be a mistake. We do have a sense of the sacred, however vestigial, and the nourishment of this sense may hold an important key to our survival. We could never mistreat our environment if we saw it as holy; we could never destroy our cities if we saw them as holy places, sacred objects, gracious goddesses to be loved and glorified. Today, the goddesses are tattered; but we must take reverence where we find it, and listen to the voices that speak to us even from our mistreated stones.

What, then, is holy in our secular culture? In the well-defined world of codified religion, a church or synagogue is sacred, because it is the House of God; objects like Bibles, holy vessels, rosaries and the like, are holy, because they are used in worship or bear the word of God. Yet the things labeled holy by that body of practices called religion do not exhaust the category of holy. "Spiritual values," the psychologist Abraham Maslow has written, "have naturalistic meaning . . . they are not the exclusive possession of organized churches . . . they do not need supernatural concepts to validate them." Feelings of reverence, of the desire to worship, of exaltation and of dread before a power greater than the merely human are infinitely older and more fundamental than any organized religion, and, in fact, underlie organized religion. In a secular culture, holy objects and holy places are often disguised as "historic monuments," "sentimental landmarks" and "tourist attractions," such as the Liberty Bell, the Alamo and the Empire State Building. Like the more certified shrines of institutional religion, these objects and places fill our need for physical, psychological, and cosmic orientation and mediate our contact with the larger universe; they provide a center for our identity and offer us a place in which, momentarily transcending our usual selves, we merge with past, with future and with eternal being.

Landmarks of Space and Time

A holy place orients us to our position in the physical world, in time, and in the cosmos. The ancient Greeks thought the navel of the world was at Delphi. It was represented by an actual stone, and myth connected it with the victory of the god Zeus over his father Kronos. Intending to devour Zeus, Kronos swallowed the stone instead; Zeus vanquished Kronos to become king of the gods, and installed the stone at the center of the earth. The spot was thus intimately connected with the divine order of things and to the stability of the universe. The temple of the Ka'aba in Mecca, which contains the Black Stone, toward which all Moslems face in prayer, has its corners oriented toward the points of the compass. It, too, is a point from which all lines of force proceed, a point of reference by which the individual worshipper's own position is defined. These landmarks tell us which way is north, which way is south and from which direction the power in the universe is flowing.

All peoples have such points of reference; nomadic peoples, like the Arabs, not only have their holy shrines at Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem, but direct their movements by the location of oases, and the unchanging stars. Our own great secular landmarks, too, provide both physical orientation and a sense of place without which we wander without compass or point of reference. The Empire State Building (from whose top, lines of force flow, in the form of radio and television waves) tells us what city we are in; and, visible from many points in the city, orients us in the undifferentiated grid of Manhattan. Grand Central Terminal, too, provides a visual focus of unique beauty and crowns, with its magnificence, a major point in its city's communication and transportation system. It is at once a landmark of space and of time. If most people are asked, when and where would you meet a person in New York if you knew the day but not the time or place?" Most people answered, "at noon, under the clock at Grand Central."

A sacred place, whether man-made or natural, often looks different from its surroundings. The visual separateness of the object not only orients us physically, but increases our sense of its specialness, whether it is the blackdraped cube of the Ka'aba or the distinctive silhouette of Mount Fuji. The Empire State Building, Grand Central, and the Brooklyn Bridge focus our attention by their distinctive personalities, even while they symbolize New York, just as the Golden Gate is San Francisco, the Eiffel Tower is Paris and Fuji, the sacred mountain, is Japan. When a sacred place does not look different, it must be made so. The intersection of Hollywood and Vine in Los Angeles is a sacred place (symbolic center of the movie industry); but unlike Times Square ("the crossroads of the world"), whose triangular shape and bright lights define its appearance, it had no extraordinary buildings or other objects to distinguish it from any other street corner. The problem was partially solved by erecting new giant street signs.

The Permanence of Stone

Stones and crystals often have symbolic meaning. They are symbols of the Self and of immortality; as the Jungian psychologist M.-L. von Franz has written, "... while the human being is as different as possible from a stone, yet man's innermost center is in a strange and special way akin to it (perhaps because the stone symbolizes mere existence at the farthest remove from the emotions, feelings, fantasies, and discursive thinking of ego-consciousness)." The Delphic stone, the Black Stone of Mecca, the "philosopher's stone" of the alchemists, tombstones, birthstones, and cornerstones all testify to the symbolic meaning of stone, especially in those stones that call attention to themselves by their unusual appearance. Buildings are man-made stones, whether built of native rock or shining like crystals of glass and steel. By their relative permanence, they symbolize something permanent in the universe and in the human psyche. This should be remembered both by those who build them and by those who tear them down. The best buildings express what is best in ourselves, and, although their demolition is sometimes necessary, they can never be demolished without a massive psychic protest, a change of position in the balance of eternity.

Cities--Symbols of Wholeness

Cities, too, are man-made stones and landmarks which orient the viewer. Fabled cities like New York, San Francisco, Las Vegas or even Disneyland are distinguished from the surrounding countryside by their greater concentration of buildings, by their height or by their bright lights. The more a city (or its central portion) achieves a symmetrical or compact shape, the more it approaches the shape of the mandala, the circular image that is an object of meditation in Buddhist and other Far Eastern religions; this shape is, to borrow again from Jungian terminology, a symbol of psychic wholeness. Many cities, past and present, have been built with circular plans, from primitive Rome to Washington, D.C. As another Jungian, Aniela Jaffe, writes, "Every building, sacred or secular, that has a mandala ground plan is the projection of an archetypal image from within the human unconscious onto the outer world. The city, the fortress and the temple become symbols of psychic wholeness, and in this way exercise a specific influence on the human being who enters or lives in the place." Mandala-shaped cities often have a sacred stone or temple at their center, an object that connects them with forces from the other world. The position of the Empire State Building at the center of Manhattan adds to its impact as a symbol of New York.

Evolved in response to practical needs for greater density, today's cities owe their shapes to many accidents of history and geography. Yet, based in archetypes that are part of our unconscious heritage, the shape of the self-contained city answers to a need that is no less real because we are unaware of it. Cities, like San Francisco or Manhattan, that are surrounded by water, are in less danger of losing their satisfying compactness than those with no natural boundaries; but urban sprawl, undermining the city's separateness, weakens its ability to orient us spatially and its capacity to serve as a unifying symbol.

In ancient times, cities were holy because they were the homes of particular gods or goddesses. Or they might be holy because they had been built by gods, or because the cities were themselves divinities. But for a more modern example, we need look only as far as Brooklyn Heights, where an inscription over a doorway next to Plymouth Church proclaims the church house "Erected to the Glory of God and the Adornment of My Beloved City." Linking City with Deity, these words describe Brooklyn as a person to he loved, cherished, and revered, to be adorned, like a favorite mistress. Pericles, too, in his Funeral Oration for Athenian soldiers fallen in the war with Sparta, exhorted the men of Athens to "become her lovers."

Cities with Mythic Personalities

Personification and allegorization ascribe human characteristics to things, and are a way of identifying and getting in touch with the spirits that dwell within them. Out of love or fear, we give a name to the spirit of the rock, the tree, the bear, the river, the building, or the city. Names like Carnegie Hall, Brooklyn Bridge, Wrigley Building or Faneuil Hall are more than labels to help us find an address; they are names of individuals to be saluted as we pass, or to invoke, as Hart Crane invoked, in his poem, the divinity of the Brooklyn Bridge: "Unto us lowliest sometime sweep, descend / And of the curveship lend a myth to God."

Today, the statues of "Brooklyn" and "Manhattan" embarrass us with their sentimentality, and are relegated to a museum; the cult of the city has gone underground, surfacing occasionally, like primeval spirits who refuse to leave a place, after official science has declared them dead. But passionate city-lovers find their pleasure (as O. Henry did, seventy years ago) in comparing the mythic personalities of various cities--New York's dazzling aloofness, Chicago's earthy strength, the gaiety of San Francisco or New Orleans; O. Henry saw Pittsburgh as "a royal and generous lady ... homely, hearty, with a flushed face, washing the dishes in a silk dress and white kid slippers." To some, Boston is The Little Old Lady, Philadelphia the elderly gentleman. San Francisco is a comfortable friend to come home to in "I Left My Heart in San Francisco"; New York is a friend in deep trouble in Cashman and West's "City Suite" ("They tell me that a friend is dying"); Chicago is a woman of whom another woman can be jealous in "Lucky Chicago" (where Jody Miller sings, "Lucky Chicago gets to spend the night with you, but Chicago doesn't need you half as bad as I do").

The nicknames of cities define their personalities and the character of their myth. Some are descriptive and utilitarian (Detroit: "Motor City," "Motown"); others chamber-of-commerce complimentary (Boston: "The Athens of America"); some diminutive or affectionate ("Big D" for Dallas; for Los Angeles "L.A."; for Philadelphia "Philly," evoking images of a tall, aristocratic racehorse). San Francisco (like a certain aunt of mine) considers it beneath her dignity to be called by any nickname, though many, with no malice, call her "Frisco." Boston's other nickname, "The Hub (of the Universe)," places that city at the center of the cosmos, around which all else revolves. Los Angeles (like New York, a city of wonder and outrageousness beyond definitive characterization) approaches the mythic with a paraphrase of her name, "The City of the Angels." New York herself, indescribable except by irony or metaphor, is "Gotham" or "The Big Apple"--the latter with a hint of evil and success, at once the apple from Eve's garden and the prize of attainment, the big brass ring. New York and San Francisco are to many of their residents just "The City"--just as the Romans, too, said Urbs--and meant only one city, Rome.

A holy place is a place of pilgrimage. As the pious Moslem visits Mecca or Medina and the ancient devotees of Demeter's Mysteries made their way to her shrine at Eleusis, the modern pilgrim goes to Washington to see the Capitol and the White House, and to Philadelphia to see the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall. Just as every Japanese wants to climb Mount Fuji, the East coast tourist visiting California wants to stand at Hollywood and Vine, and the Californian grows up yearning to visit the fabled Empire State Building and Statue of Liberty, Harvard Yard and Times Square. There are places that one must visit (or be greeted with "What, you haven't been to ...?"). When the tourist says, "It's a nice place to visit, but I wouldn't want to live there," he is really saying, "Though I wouldn't choose it for a home, it is obligatory to have been there." Not every Japanese would want to live on top of Fuji, either.

Settings for Modern Rituals

The stones and streets of holy places are stages for great myths. Mankind's universal myths revolve around the great life crises, focal points of our lives, like birth and death, puberty, marriage, sickness and the communal meal. Civilizations from deepest antiquity to the present have built their myths around these points, chronicling the conflict of the generations in the Succession Myth. the individual's attainment of maturity in the Hero's Birth, the Combat With the Monster, the Journey and the Encounter With the Goddess Across the Water. Important religious rituals mark these same life stages. Baptism, confirmation, bar mitzvah, communion, weddings, last rites and funerals are all designed to celebrate these stages and smooth the individual's way through these mystic and dangerous moments in his life. Many people stop going regularly to church or synagogue but still want a religious wedding, want their children baptized, or want a religious funeral. In secular soeiety, the young person's induction into adult society is marked by getting his driver's learner's permit, and the cocktail party or pot party is today's secular communion.

Holy places, too, are often linked with the life crises and the great myths, the mythic act conferring significance upon the place and the place ennobling the event. Birth and resurrection are celebrated at New Year's in Times Square; the Empire State Building, a sacred mountain rising in exquisite grandeur from the valleys of Manhattan, is fenced at the top to prevent would-be suicides from duplicating King Kong's heroic death; but the Gothic bulk of the Brooklyn Bridge, like San Francisco's Golden Gate, is a favorite for this particular life crisis. Philadelphia's Liberty Bell is a monument to the Creation Myth (celebrating the creation of America), like Texas' Alamo (where Texas was born). The Staten Island Ferry is a much-beloved Journey, as are San Francisco's cable cars. And the great railroad terminals like Penn Station and Grand Central provided--and Grand Central still provides--a splendid stage for many great journeys into farthest America.

Just to have been to a holy place is not enough. One wants to do something that will celebrate one's visit appropriately, something that will put one in touch with its mana, the force or spirit emanating from it and will let the visitor participate in its nature and in that of the divine presence inhabiting it. The ritual is different for each place. A visit to the Empire State Building should be celebrated with a ride to its top. To be paged in Grand Central is always a thrill--a ritual of public recognition for the importance of one private journey. The ancient solstice festival is celebrated in Times Square by lowering a shining ball; the spring fertility rites by the Easter Parade on Fifth Avenue. Myths are acted out every night on that other fabled street, Broadway; and the Hero of Light vanquishes the Monster of Darkness several times a week at Madison Square Garden and Yankee Stadium.

Holy places are often bound up with history. A holy place is a landmark in space; a historical event is a landmark in time. Where the two coincide, their force is twice as great. Places acquire mythic importance by the events that have taken place there or are supposed to have taken place: the Liberty Bell, Paul Revere's Old North Church, the Alamo, the spot where Babe Ruth hit home runs, and the building King Kong climbed--all have been touched by some power, and we receive some of their magic when we stand there.

Holy Places and Real Life

Cities, buildings, and other sacred places fulfil their nature best when they have a real function in real life, not pulled brutally from the fabric of their surrounding world. In those societies where life revolves around organized religion, as it did around Christianity in the Middle Ages, an actual church or temple is the most natural point of orientation. It is located in the center of the town and is housed in its most distinctive building. Our sacred places, too, cities, streets, or single buildings, should be used, inhabited, made part of our lives. No amount of "Williamsburging" or artificial preservation in cultural ghettos can take the place of daily use and intimate relationship. Mythologically as well as commercially, it was more appropriate to replace Penn Station with Madison Square Garden than to embalm it as a museum or a greenhouse, as some suggested. The tragedy is that both Penn Station and Madison Square Garden were mythic places (once housed, both of them, in McKim, Mead and White masterpieces), and both served useful purposes. New York could have used both buildings, but one cannibalized the other, and both were reduced to the status of barest utility.

But the nature of a holy place is most fully realized by its truly numinous functions, which connect it with the eternal, with the force pervading the universe. For holy objects do more than point to the direction from which the cosmic force flows; they contain some of that force themselves--like the stone, with its eternal, enigmatic act of existing. Some buildings and other places, too, arrest our attention by their size, their beauty or by a spookiness or "presence" that transforms and exalts the visitor. Thomas Wolfe said of Pennsylvania Station, through whose vast room so many passed on the journeys of their destiny, that it "held the sound of time." The Empire State Building, whose presence dominates the chasms of midtown Manhattan, has a force that resides in its tallness and isolation, accentuated by the strength of its masonry, its graceful shape, and fine proportions. From its top, the visitor sees the city with omniscient eves, to embrace with the pity of a god. Those who perceive beauty as divine will understand the connection; but the phenomenon of numinosity is not identical to the aesthetic response. Gertrude Stein once said that the trouble with Oakland, California, was that there was "no there there." The "there there" is that presence, that sense of some power within, that stirs us. The "excitement" of a big city, that feeling that this is where something wonderful is about to happen, bespeaks such a presence, such a fusion with something greater than oneself. To look upon, to enter such a place, is to experience the union of the individual with the universal and eternal, which is at the core of every mystical, ecstatic experience, and is, perhaps, the most truly moving of all life crises.

The Destruction of Rival Cults

From the impressive experience of the transcendent, we turn to its destruction. Archaeological exhibits from the sites of Athens and Rome, Babylon and Egypt, are a familiar sight to the museum-goer, with their dusty artifacts of remote civilizations, crumbled and fallen far from us in place and time. But in New York there is an archaeological display that must rank among the saddest of all. It is the Sculpture Garden of the Brooklyn Museum; in it are the usual marble fragments, statues, and painted pottery. Its exhibits are carefully labeled and maintained, but it is deadly in its appearance of normality. For these are no ancient monuments, brought from the rocks of the Acropolis or the sands of the Nile. They are all from buildings demolished in New York, and they date from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries A.D. A few battered railings and terracotta ornaments, lions still threatening in stout bronze; a broken statue and a bit of column from Penn Station--their numinous presence reduced to the dimensions of these poor relics. They are the pitiful shards of our own civilization, needlessly destroyed by ourselves.

The ancient peoples believed that to destroy a holy place incurred the wrath of the gods. If this were so, the gods would surely be against us. The physical demolition of our buildings is only one aspect of a more subtle and widespread destruction of our cities, which we ravage by pollution, by abandonment, by discriminatory taxation and by our lowered expectations of what urban life can be. Social, political, and economic problems of massive proportions must be solved if order is to be restored to our urban institutions. Yet before any practical action can be taken, there must be the will to action, a rationale for why the cities should be saved. Once an urban ideal is established and accepted. we can begin to solve the practical problems. In addition to the various reasons that have been advanced for saving the cities, their functional value as sacred places should furnish us with one more. A sense of reverence and a recognition of the practical necessity of holy places to define our psychological and cosmic space are the beginnings of a desire to build and to conserve, rather than to destroy. One does not defile what one reveres. In our sophistication, we have forgotten the anger of the gods. But perhaps in the destruction of our cities, we destroy something more important, our souls.

Our lack of reverence for our buildings and other holy places of our secular world has been attributed to the practicality of Americans, who do not keep a thing when it is no longer "useful" in some narrowly defined sense, and to our puritanism, which distrusts the sensual and delightful. But it is truer to say that there are rival cults. America herself, whom we associate with the Deity in such phrases as "In God We Trust" and "One Nation Under God," is personified as a lady of seductive yet maternally pure attractiveness--"Lady America." Her symbol is the Flag, for whose display elaborate ritual is prescribed. Anti-urban from the beginning, despite the evocation in "America the Beautiful" of "thine alabaster cities," America was founded on the pastoral myth of regaining lost Eden, far from the mephitic cities of the Old World, a fantasy still followed in the flight to the suburbs.

Technology is America's other myth. Conceived at first as the means of achieving this new Eden, it soon took on meanings of its own as a mythology, providing a cosmology, a source of psychic orientation and an object of worship. Idols of the new religion were the machines themselves--yesterday the thundering locomotive, today the electronic computer, a device that seems, in its mimicking of rationality, to be an oracle of divine infallibility, a god to be worshipped and propitiated, like the dynamo to which Henry Adams, in 1900, felt the impulse to pray. Our worship of technology should have made us careful of our machines, our buildings and our cities. And we do love them, for a while. We wax and shine our cars, we provide our buildings with the finest glass and elevators and airconditioning. But in a few years they are destroyed, discarded for something newer. For Science, in America, is the handmaiden of Progress, a stern Moloch who demands the destruction of everything that is not Up-To-Date.

Exempt on occasion from destruction is the architecture called "Colonial." Considered suitable for historic shrines and hamburger stands alike, "Colonial" buildings are an attribute of America almost as sacred as her Flag. Particularly during the Bicentennial, we honor the heroes of the Revolution (deified ancestors and eponymous heroes of America) by erecting motels and snack bars sheathed in red brick and white pseudo-shutters--curiously, we honor the patriots by erecting the architecture of their oppressors; for "colonial" was precisely the style of a period of English colonial administration so oppressive that it moved the colonists to revolt. As soon as the revolution was over, American architects turned to the Greek revival style, a being more symbolic of democracy. It is this Classical architecture that is now endangered and forgotten. Much of today's "Colonial" construction is new, for Americans are uncomfortable with genuine old buildings. Real old is torn down for fake old, or old buildings are restored to false youth with copper counter-tops and self-conscious gaslights. "Colonial" is designed to honor America, but the newness is in the name of Progress.

Reverence for the Man-Made

Environmentalists of the wilderness are far ahead of urbanists in awakening a sense of reverence for our physical environment. The persistent cult of Nature (that divinity of the nineteenth-century Romantic) has made us more attuned to the numinous and salutary force of rocks and trees than of our manmade rocks and chasms. "Go to the woods and hills--" wrote Longfellow, "no tears / Dim the sweet look that Nature wears." Today's environmental movement, inspired less by Longfellow than by the American Indian in its respect for nature's balance, has gained new followers because of the energy crisis and our new awareness of our depleted resources. We are only now awakening to how the destruction of the built environment also drains the resources at our disposal. Yet the urbanist can also learn from the environmentalist that sense of reverence for places and things around us, without which we will continue to destroy our physical world, and ultimately ourselves.

We cannot keep everything, for all things must change in order to survive. Nor can we return, with nostalgic longing, to a static world of an imagined past. Nostalgia is a substitute for history for those who have lost hope. Where the optimist believes that the past is a living part of the present and that it will teach him something of value for the future, the pessimist, having given up on both present and future, moons over the past and trivializes it. Change tempered with reverence is a better goal. While the pulverization of Penn Station, and its use as landfill in New Jersey, where no future archaeologist can reassemble it, ranks in barbarity with Rome's sowing of salt on the site of Carthage to prevent its resettlement, the eagles, the president of the Pennsy, the broken statue and one column are better than nothing; reminders of our destructiveness, they are also a fingertip's touch with the numinous. Perhaps, like the American Indians who pray to the soul of the animal they kill, we should offer a prayer to the spirit of the building we are about to destroy. This practice might result in fewer killings of buildings.

Holy places are our link with past and future, pointers to the forces in the universe and to the direction in which our well-being lies. In our new construction, as in our preservation, we must remember that we are constantly creating holy places, and they should be worthy of their function. Upon graduation from the City College of New York, students take an Ephebic Oath, modeled on that of ancient Athens, "We will fight for the ideals and sacred things of the City, both alone and with many." Meaning should be restored to those brave words, The city is whatever its people beleve it to be; if we see it as sacred, it will be worthy of our reverence. "Brooklyn" and "Manhattan"--yes, and Boston, and Detroit, and the other cities--cry out for our belief.

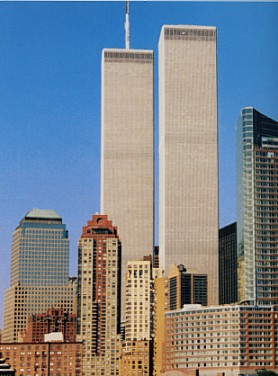

Epilogue on the World Trade Center

The World Trade Center, double obelisk in the center of the holy

mandala that is lower Manhattan, site of the foundation myth of New York

and first capital of the fledgling United States, was built too late for

inclusion in the original version of this article. A section on the

Trade Center and its place in our mythology has now been added. Click on

the title to read "Epilogue to 'Holy Places': the

World Trade Center as a Mythic Place".

The World Trade Center: an image imprinted in our minds

Copyright © 2001, Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Number:

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.