Epilogue to "Holy Places": the World Trade Center as a Mythic Place

by Dr. Cora Angier Sowa

The World Trade Center: an image imprinted in our minds

A summary of the essay:

In "Holy Places", first published in New York Affairs in 1977, I discussed the role of landmarks like Pennsylvania Station, the Empire State Building, the Brooklyn Bridge, and cities such as New York as sacred places, landmarks that orient us physically and spiritually. About them powerful myths of origins and life crises like birth, death, marriage, and transcendent intersections with the divine collect and swirl. They are centers of mana or spiritual force. The World Trade Center, tragic landmark of beginnings and endings, of hopes and aspirations, and of sudden disappearance, was only then being completed and was not described. This epilogue places the Twin Towers, cut down, alas too young, by terrorists flying highjacked airplanes into them in 2001, in their mythic context. It has been said that since the disaster, with its great loss of life, the area is now a "sacred place." But the site has always been sacred, since long before the Trade Center was built, going back to the earliest days of New York, and before that, to the Lenape Indians. The unique architecture of the towers, beloved by many, criticized by others, was iconic, adding to their mystique. Rebuilding the site in some form as a vital urban center will carry on the mythic significance and spiritual symbolism of the place, perpetuating its function, both real and legendary, as a psychic center, a source of dynamic energy and a place of trade.

The World Trade Center as a Mythic Place

The shape haunts us

The shape haunts us, an image imprinted in our minds. The two shining pylons, anchored in the middle of downtown Manhattan like the stone in the mandala, marked a holy place in our mythology.

Even before the disaster, this area was numinous, a center of spiritual force. Founding place of New York, it has its foundation myths, just as Rome has her Romulus and Remus and Mexico City her snake-devouring eagle. The seat of Dutch traders (for whom Washington Irving created the myth of Father Knickerbocker) and of English merchants, it became the capital of the newborn United States. There Washington took the oath of office and Hamilton is buried. In the neighborhood are located Federal Hall (not the original, but impressive), Fraunces Tavern (the original, rebuilt), the Battery, with its view of the goddess-like Statue of Liberty, and the antique wharves, preserved in amber as the South Street Seaport. The stories of the place include other disasters. Lower Manhattan was burned down under British occupation during the Revolution and was rebuilt. Wall Street was bombed in 1920 by terrorists (or anarchists, as they were then called); gouges are still visible in the massive walls of the Morgan Bank building at the corner of Broad Street, across from the New York Stock Exchange. African freemen and slaves are buried in the recently discovered Black cemetery near the new Federal Building. Artifacts of earliest settlements are still being found; many were discovered during excavation for the foundations of the Trade Center. Go back in time before any of these, when Manhattan's tip hosted a Lenape Indian settlement, where the inhabitants lived, worked, died, and celebrated rites on their sacred island.

New York City is a place where fortunes are made (and lost), where the individual can strive for a better life, look for love, seek to become a new person. The Twin Towers expressed, in their visual symbolism of reaching for the sky, that yearning for something higher, something transformative, perhaps unattainable. In their function, they were office buildings whose ambitious, hard-working inhabitants carried on the business of trade, giving physical expression to that exuberant quest.

Now that the Towers and the people in them are gone, we seek to recapture the dream by obsessively recreating the image of their unique shape. As Richard Dreyfuss compulsively made models of the cone-shaped mountain of his dreams from mashed potatoes, garden dirt, and other things in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, we recreate the Towers out of anything that comes to hand. Twin Towers of white roses went on display in a store window in Soho after the disaster. Murals depicting the towers have appeared, including one imaginatively showing the towers in heaven with angel wings (illustrated later in this essay, under "Sacred Relics and Holy Pictures"). The shape is represented calligraphically (four elegant brushstrokes) on sheets of paper posted on various memorials (pictured below under "As a Work of Architecture and Abstract Art").

Like the protagonist of Close Encounters, we see the shape in

everything. We see the image in the "11" of "September 11" and

"Channel 11;" I see it in the gray rectangular speakers of the CD player

on my desk. We collect pictures of the skyline that show the

fondly remembered towers, advertising throwaways like the Gristede's

yellow plastic shopping bag and the Chock Full O' Nuts coffee can.

Even before September 11, the shape was catchy. In Eric Darton's

Divided We Stand, a "biography" of the Trade Center, the type is

set in twin columns on the first page of every chapter. The World Trade

Center, the Empire State Building, and the Chrysler Building were

portrayed whimsically as sand castles on the cover of the August 6, 2001

New Yorker. The Downtown Alliance makes twin towers of the

two l's in its name, whose other letters "spell out" various buildings on

the skyline. The shape has a mesmerizing influence, like the

black slab in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Wishing to possess what we

have lost, we collect pictures and models of the Trade Center, in pewter

and crystal in tourist shops, in Christmas ornaments and lapel pins.

In March, 2002, the Municipal Art Society erected a temporary memorial of

two shafts of light in Battery Park, ghosts of the buildings.

There is mourning not just for the people who died but for the two

extraordinary buildings, landmarks that anchored our view, dependable,

reassuring friends. We collect their icons and holy pictures.

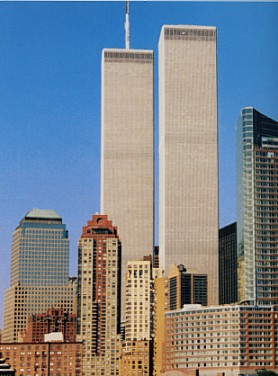

The World Trade Center as a keepsake to recapture the dream

(photo by C.A. Sowa)

A landmark orients us physically and psychically

Landmarks, as I wrote in "Holy Places," orient us not only to our place in the physical world but to our place in time and in the cosmos. The Greeks believed that the omphalos or navel of the world was at Delphi, where it was represented by an actual stone, supposed to be the one that the god Kronos swallowed, thinking it was Zeus, then spewed up again. The Black Stone of the Muslims is in the holy city of Mecca. Our sacred places may be associated with a particular religion, but in our secularized Western world, holy places are often disguised as "historic monuments" or "tourist attractions." Their significance lies at a deeper, more fundamental level. What the psychologist Abraham Maslow called "core-religious experience" or "transcendent experience" needs no supernatural concept to validate it, and, in fact, underlies organized religion. Our landmarks, as I wrote in "Holy Places," while they may sometimes of necessity be torn down, can never be demolished without a massive psychic protest, a change of position in the balance of eternity.

The World Trade Center towers could be seen from virtually everywhere in New York City and its vicinity. They were a point of reference; you knew where you were by looking at them. Their destruction, and now their absence, was widely seen. Sixth Avenue, once anchored at its southern end by the Trade Center, now seems to go on dismally forever; Route 22 in New Jersey, with a view whose focus was provided by the towers, has been described as now looking like "just one more shopping strip." Streets like Macdougal and Sullivan in Greenwich Village, formerly bracketed at their ends by the Empire State Building and the Trade Center, assault our eyes with a hole in the sky at one terminus, making us cherish Empire State more than ever. The city itself seems to have been mangled. There is a sense of disorientation and psychic shock at seeing its lack of wholeness.

Worldwide, the Towers were a symbol that identified a place, saying "This is New York." Souvenir shops still show more postcards of the World Trade Center than of any other New York landmark. It is said that illegal immigrants often arrived with no official papers, but clutching postcards of the World Trade Center.

Landmarks are centers of mana or spiritual force and energy. Not only was the World Trade Center located among shrines of the historic foundation of New York, but "lines of force" in the form of radio and TV signals flowed from the Trade Center's antenna (as they still do from atop the Empire State Building). A tangle of subways, trains, roads, and tunnels still meet at the site, inviting people's paths to cross, people who live there, work there, or are passing through. In folklore, the crossroads, where strangers meet, are always haunted by spirits, marked by magic rites.

An icon of many meanings

The towers were an icon of many meanings. Some saw them as two prongs of a magnet drawing immigrants to our shores. Others saw them as a mighty tuning fork, sounding the harmony of the living city. A letter to the New York Times called them "New York's punctuation: two exclamation points." Many saw them as the pylons of a mighty gate, the portal into a promised land, complementing the Statue of Liberty, which was often photographed against them. Newsweek desribed them as "The Ellis Island for international businesses." They could be seen as two parallel lines or lanes of a highway, meeting only in infinity. Looking at the towers on a brilliant day, I often saw them as two shafts of sunlight reaching for the heavens.

They were fascinating in their two-ness. Were they friendly twin guardians or terrifying clones? We start to notice other twin buildings: two towers on churches like St. Patrick's, on the Central Park West apartment buildings and the new AOL Time Warner Building, on bridges like Brooklyn Bridge, even the double structures of the Hudson and Manhattan Terminal Buildings that formerly stood on the site of the WTC. One building that is starkly different from its neighbors looks lonely, out of place, but a plantation of identical slabs, like a housing project, is banal; two together make an abstract sculpture. We are fascinated with duality--binary numbers, good and evil, love and death, North and South, East and West, yin and yang, complementary opposites. Interestingly, a previous destructive act of the Taliban protectors of terrorist Osama bin Laden was to blow up the gigantic twin statues of Buddha in Afghanistan.

The Twin Towers, though adjacent, were not actually side by side on the same axis, and the off-center positioning made a more interesting composition, which changed as you moved around them. In fact, they were often portrayed in such a way that one was closer, appearing taller, the antenna on the north tower enhancing the asymmetrical effect.

The sacred stone in the mandala

The mandala, the circular object of meditation in Eastern religions, is a symbol of the universe. The Jungian Aniela Jaffe wrote that "Every building, sacred or secular, that has a mandala ground plan is the projection of an archetypal image...The city, the fortress and the temple become symbols of psychic wholeness, and in this way exercise a specific influence on the human being who enters or lives in the place." Mandala-shaped cities often have a sacred stone or temple at their center, an object that connects them with forces from the other world. Many a great city (or even small city or village) is a mandala, whose center (which may be only the village green or a war memorial) is often connected with its own mythic history. New York and San Francisco (New York with its skyscrapers, San Francisco on hills even before it had skyscrapers), both surrounded by water, naturally have the shape of a mandala or sacred crystal. Even Los Angeles (admittedly influenced, as are all cities, by real estate and commercial interests) felt obliged to create an upward-thrusting downtown.

New York had two sacred stones, the Empire State Building and the World Trade Center. The Empire State Building, proud and isolated, its aspect unblocked by other structures, was for many years, and is now again, sadly, the one true center stone in the mandala of Manhattan. King Kong validated its stature with his mythic climb. The World Trade Center, during its tenure, was the psychic center of a renewed and reconfigured lower Manhattan, and became the new center of the mandala. The shift was confirmed in the remake of King Kong, in which Kong's mana is transferred to the new towers. The Twin Towers were not originally at the center; before the old wharves were destroyed, before the infilling of the land, they seemed to visually overweight the island at one side. But a mandala grew up around them in the form of the World Financial Center and Battery Park City.

After the bombing of the Twin Towers in 1993, Buddhists from the Dalai Lama's Namgayal Monastery created an actual mandala of sand in the lobby of Tower 1. For a month, they invited visitors to participate in its construction, as a symbol of nature's unending wheel of creation and destruction. At the end, they returned the sand to its source, by offering it to the Hudson River.

Stones and crystals are symbols of permanence and immortality;

hence there is an added shock at their destruction. It is appropriate

that the World Trade Center, a sacred crystal, now is found sculpted in

crystal in gift shops. The Trade Center itself had the shape of

a mandala, consisting of buildings around a central plaza, and it had its

own sacred omphalos, or navel, like the sacred stone of Delphi.

This was the (originally revolving) bronze spherical sculpture in the

middle of the plaza. The sphere survived the destruction, battered but

whole, and is on display, at this moment, in Battery Park, perhaps

eventually to be restored to a more central location.

The sacred omphalos: the sphere from the World Trade Center plaza (photo by C.A. Sowa)

"There's a hole in my city and in my heart"

The tearing out of the sacred stone from the mandala causes both a physical and a psychic gash. A sign affixed among the memorials at the esplanade on Staten Island, next to the ferry terminal, which commands a view of the harbor and lower Manhattan, expressed grief for the ravaged skyline:

"There's a hole in my city and in my heart"

One feels physically sick at the sight of the great hideous hole in the sky, struck with a sense of desecration, violation. The self-deception that the buildings ought still to be there has been compared to the amputee's illusion of the "phantom limb." In "Holy Places," I spoke of looking at Madison Square Garden and seeing, instead, the imagined contours of Pennsylvania Station. In the place of the World Trade Center, one's eyes squint and strain to see its towers again, shining and tall; one tries to remember exactly where they were, how tall they were, what they would look like at this time of day.

Nostalgia is a misunderstood word, denoting to some a trivial or flippant whim of fashionable taste. Those who long for the Trade Center to be rebuilt are accused of nostalgia. But it is a serious emotion. The word nostalgia comes from the Greek words nostos "the journey homewards" and algos "pain;" it is a longing for a return to home, or "homesickness."

As a work of architecture and abstract art

The beauty of the "two shimmering towers" caught our imagination. Were they good architecture? What is great architecture? According to Vitruvius and Palladio, a building should have utility, durability, and beauty. Great architecture, in addition to providing us with shelter and infrastructure, has the power to move us emotionally, to comfort, to disquiet, to make us think, to surprise us, to hold our attention, to allow us to inhabit it, and to inhabit us ("Forever in our hearts" say many of the posters and T-shirts commemorating the WTC.) Sometimes it is enough just to make us feel at home in it. A building can also tell us something, narrate a story (a monument), or express a philosophy. Some architecture makes us laugh, like a Long Island diner shaped like a duck. Some structures, by their delicacy or ornateness, implore us to protect them. Others lift us with a sense of awe and sacred ecstasy, like the immense stone piers and cables of the Brooklyn Bridge, plunging at their base, mysteriously, into the East River, then ascending to flag-tipped heights. Hart Crane wrote of it

And of the curveship lend a myth to God.

To the people who worked in them, the Towers were a home, a village.

Visually, with their tall, rectangular smokestack silhouette, they

perhaps most resembled the mediaeval Italian towers of San Gimignano.

They were, especially from afar, a work of abstract sculpture.

Not symmetrically placed on the same axis, but slightly offset, they

changed their form as you moved around them. The color of the aluminum

sheathing changed with the light, at times gray, peach pink or gold.

Sometimes you saw the vertical ribs; at other times, you saw the gleam

of their beveled corners or the effect of shining ribbons tied around

them one third and two thirds up their height. Only at night could you

see individual windows, lighted up as in ordinary, but huge, office

buildings. You could see them at a distance, as two great, enigmatic

cliffs, or close up, where one's eyes were lifted by their soaring height.

As an abstraction, their shape is easily reduced to an ideogram, as seen

below:

The World Trade Center etherealized: an ideogram rendered in calligraphy (drawing by C.A. Sowa)

Stylistically, the World Trade Center was difficult to categorize. More highly decorated than the glass boxes of the International Style, with its striped aluminum skin covering the steel exoskeleton, whose columns widened into more broadly spaced "Gothic trees" at their base, it lacked the visual vocabulary of the older styles, with their acanthus leaves and caryatids, their classical arches and cornices. Built too soon to be postmodern, it did not share, either, in the new vocabulary of post-post-modern architects like Frank Gehry. The elite architectural critical establishment, harpies pursuing the latest art theory du jour, say that the World Trade Center was bad architecture. The public liked it; the disjunction between elite and popular opinion fascinated Angus Gillespie, who wrote of it in his book Twin Towers. The visual simplicity that made the WTC a powerful icon bored the critics.

Was the Trade Center kitsch? The label is applied by the elite art world to what it considers vulgar, banal, or simplistic. True art is supposed to challenge us; kitsch validates the way we already feel. The term "kitsch" is often applied to creations that ordinary people like and feel an emotional connection to. To the question "What is art?" the answer is usually something like "A chair by Breuer is art, a painting of Elvis on velvet is not." It is a question of high culture vs. low culture, but also of following arbitrary rules vs. respecting the viewer's real feelings. Artist Odd Nerdrum (rejecting the label "artist" to describe himself) defends kitsch by saying, in On Kitsch, "Art exists for its own sake and appeals to the official room. Kitsch serves life itself and appeals to the individual person." Kitsch, unlike high art, is without irony. In their simplicity and straightforwardness, the Twin Towers were perhaps the ultimate (and proudly) kitsch; no wonder they are memorialized as kitsch, to hold fondly in our hands as a little statue in a snow globe.

A question is commonly asked of jazz lovers, the answer to which supposedly tells something about the answerer: "Do you prefer the singing of Ella Fitzgerald or Billie Holliday?" Limpid clarity and flawless technique are contrasted with soul-searing emotional realism. Aficionados of architecture are often presended with a similar question: "Do you prefer the Empire State Building or the Chrysler Building?" Calm, classical repose is opposed to wild deco flights of fantasy. What did the World Trade Center tell us about its admirers? I believe that to love the Twin Towers was to be ambitious, to be a risk taker, to enjoy the rush of being lifted off your feet by the experience of something great and cosmic. It was to rejoice in the hugeness and chaos of New York City itself. And it was to cherish the buildings as survivors, whose strength and sturdiness enabled them to withstand the attempt on their life in 1993. The appeal to the emotions, it seems to me, should be part of the definition of good architecture.

The Sublime and the Beautiful

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, aesthetic critics like Burke and Ruskin called "sublime" those wild, overwhelming things that did not fit into what they, following the artistic theory of the day, conceived as standards of classical, well-proportioned "beauty." "Beauty," they thought, applied to calm, reposeful objects like ancient Greek marble statues. "Sublimity" was a word applied to such things as mountains, great chasms and waterfalls. Kant also distinguished between "beauty" and "sublimity." Seeking a terminology, the critics adopted language from the late ancient treatise on rhetoric, Longinus (or more likely pseudo-Longinus) On the Sublime.

If the sublime possessed the grandeur and inevitability of a force of nature, there was also in the sublime an aspect of terror (but mostly a pleasurable kind of terror, not real fright). As Longinus said, sublimity strikes one "like a thunderbolt." The sublime is not merely the pleasant or comely. We are reminded of the Dies Irae, where God is invoked as Rex tremendae maiestatis "King of terrifying majesty." "Sublime" is perhaps the word we should apply to the World Trade Center; not fitting our pre-conceived notions of "beautiful" or "good" architecture, it nonetheless affected us powerfully, both emotionally and physically. It is significant in this context that Eric Darton in Divided We Stand speaks of a feeling of terror inspired by looking at the sheer, superhuman, "cloned" towers of the World Trade Center.

Visible from near and far, the towers drew us to them,

like the huge, mysterious mountain that "followed" Wordsworth

in The Prelude:

|

...lustily |

A feeling of ecstasy at the experience of the sublime, lifting you out of yourself to a transcendent state, and the endeavor to maintain that ecstasy, keeping its vital force in focus, by contemplation of a work or art or an experience, was described by Walter Pater in his much-quoted phrase in the Conclusion to his book on The Renaissance, "To burn always with this hard gemlike flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life." To psychologist Maslow, the ecstasy of exaltation beyond one's own ego was a pre-religious experience, lying, in fact behind the formalism of organized religion, a peak-experience leading to self-actualization, a glimpse of the sacred in the momentary and worldly.

To the criticism that the Towers were not built to the scale of the human body, we can answer that they were built to the scale of the human spirit. They have been aptly described as two parallel lines, meeting only in infinity. The greatest landmarks invite us to go beyond ourselves, offering us an image of the transcendent. In the end, of course, whether the World Trade Center was "good architecture" is beside the point--it was already a Holy Place. The terrorists of 1993 and 2001 knew this even before we did.

The human connection

A neighborhood grew up around the towers, and more and more they found their place as a human part of the city. They were great totemic protectors, but they were the monument in the town green for residents of Battery Park City and of other buildings renovated as condos and apartments. The community of workers in the Trade Center spoke of their "village in the sky." Residents of Brooklyn or Hoboken who had offices in the Towers could see where they worked from their own neighborhoods.

King Kong and some daredevils humanized the Towers. Kong symbolically relocated the center of New York from the Empire State Building by scaling the Trade Center, and brought them within the physical scale of an ape's reach. Philippe Petit, cavorting on a tightrope between the Towers, Owen Quinn, parachuting from the North tower, and George Willig, the "human fly" who climbed up the outside, turned the mighty structures into toys. A greenmarket took root on the broad, unfinished-looking street in front of the Trade Center, and summer concerts were held in the Center's plaza, almost achieving the romantic vision held early in its planning by the Port Authority in the 1960's, of recreating a mediaeval town square and trade fair, a modern Leipzig or Piazza San Marco.

Landmarks, as I described in "Holy Places," are often settings for the great life crises--births, deaths, marriages, and journeys. The World Trade Center, at its Windows on the World restaurant, became famous for its Valentine's Day weddings. Management used this as a publicity gimmick, holding contests and providing free weddings to the winners.

For many, it was the 1993 terrorist bombing and attempted destruction of the Trade Center that awakened an affection for the buildings. For the first time, what had been, to many, an oversized white elephant, a laughing stock, was suddenly vulnerable, and therefore human. At last, it seemed truly part of the neighborhood and the city. The feeling of shared experience was poignantly illustrated by a winning entry in a Valentine's Day wedding contest: Identifying their struggle to overcome family opposition with the attack on the Towers, one couple wrote "They tried to destroy you, but you survived; they tried to destroy our love, but it, too, survived."

Love and lust for buildings and cities

Buildings and cities can be seen as people. In "Holy

Places," I spoke of the mythic figures of "Manhattan" and "Brooklyn,"

once guardians of the entrance to the Manhattan Bridge, now protectors

of the Brooklyn Museum, even in their exile "gracious goddesses to be

loved and glorified." We give our cities personalities.

O. Henry saw Pittsburgh as "a royal and generous lady ... homely, hearty,

with a flushed face, washing the dishes in a silk dress and white kid

slippers;" Boston is The Little Old Lady, Philadelphia the elderly

gentleman. Pericles, in his Funeral Oration for the Athenian soldiers

falled in battle, exhorted the men of Athens to "become her lovers."

A civic goddess at the Brooklyn Museum, in her temporary home awaiting museum renovation (photo by C.A. Sowa)

Buildings are personified, too. The Empire State Building, now that the Twin Towers are gone, is described by one New York resident as "a lonely lady, now that her two gentlemen friends are gone." An artist who loved to draw the skyline, speaks of losing "a friend that is a building." The sexual symbolism of buildings is part of their fascination. In the case of the Twin Towers it was obvious but ambiguous, in their upthrusting forms and sexy, shining aluminum "skin." Although they have been described as "phallic," the idea for the world's tallest building came from a woman PR person at the Port Authority. In their dual shape, they could as easily be seen as breasts or buttocks. Mohammed Atta's penetration of the Towers, as he piloted his highjacked airplane, was an obscene violation. Now New York the brash, high-flying, hard-shelled metropolis with the generous spirit, is, with her buildings, "wounded," and we rush to her aid.

Larry Silverstein, leaseholder of the World Trade Center from the Port Authority, is notoriously said to have told the Post that he "lusted" after the Trade Center; the media had a field day with this, but he need feel no embarrassment.

Futurists fear that computers, which partake of human reason, will take over the world, as if rationality were the only way in which the things we build can be like us. Actually, we endow everything we make with human characteristics. These include beauty, sexiness, comfort, menace, and strength. We celebrate the grace and speed and maternal shelter (and from a male point of view, capriciousness!) of ships by calling them "she." Even our computers seem to need qualities other than reason. Movies such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and A.I. Artificial Intelligence explore the theme of whether our computerized products will also feel human emotions. In Karel Capek's R.U.R. of 1920 (which gave us the word "robot"), automata are able to replicate themselves only after they rediscover emotion and physical passion, in other words, when they become more human.

Just as we write off our desire to preserve our landmarks and our environment as "mere" "sentimentality" or "nostalgia," we dismiss the human or lifelike in our creations as "personification," "metaphor," or "pathetic fallacy." Rather, we should recognize the personal and the sacred not only in ourselves but in everything we create.

The manner of its disappearance

The strange, eccentric monumentality of the World Trade Center was matched by the uncanny nature of its end. After their brush with death in the 1993 bombing, the towers seemed immortal, indestructable. But struck by a synchronized pair of highjacked airplanes (the crime itself seemed impossible, a Hollywood fantasy), they collapsed, incredibly, horribly, before our eyes. The first emotion felt by onlookers, across the city or watching on television, was disbelief. One glorious moment they were there, then they weren't. Black smoke and falling debris, then white smoke, then empty sky. The buildings were gone, the inhabitants vaporized. The World Trade Center did not seem to be destroyed; it simply vanished.

Like Brigadoon (or its German literary forebear in Friedrich Gerstäcker's Germelshausen ), the World Trade Center's village in the sky, together with its villagers, disappeared into the mists. Brigadoon and Germelshausen reappeared periodically, like the heroes Amphiaraus and Oedipus of Greek legend, who were swallowed up by the earth, but were still alive, and could be called on as immortal seers. Like Elvis and Marilyn, the World Trade Center died young. We keep seeing them, as we squint at a reflection, or their images, or their ghosts. We look out of the corner of our eye, catching some echo of the familiar shape, and think, can the World Trade Center, too, reappear?

The sacking of the Trade Center was the death of a symbol of our identity. So much was it associated with our sense of who we are, as New Yorkers and as Americans, in all our gaudy, carefree, overreaching, ambitious, yet community-loving nature, that its destruction seemed, even to those who did not actually know those who died there, to have taken away some part of ourselves. In that feeling of devastation, ordinary pursuits seemed trivial. New Yorkers, it has been much remarked, became uncharacteristically polite following the disaster, eschewing the usual honking horns and impatient insults. Small slights no longer mattered, as if any unnecessary disturbance might upset the delicate balance with the cosmos that was reached. Landmarks are always centers of community life; the destruction of the Trade Center was a communal event. The same fog of smoke and eye-stinging ash infested the entire city, and the same fighter jet patrolled monotonously over everyone's sky.

The World Trade Center, like the Titanic, was the flagship of a gilded age. Both took with them the flower of society, the young, the rich, and the ambitious, as well as those of more modest means who worked for them. The Trade Center, like the Titanic, represented narcissism, hubris, instant millionaires, and mad ambition. Their guardians ignored sober warnings of danger ahead, icebergs for the Titanic, terrorist threats for the Trade Center. The sinking of the unsinkable and the destruction of the indestructable shook the faith of each gilded age, especially for a younger generation who did not remember previous depressions, wars, or other disasters. For both the Trade Center and Titanic, the end was sudden. Like Pompeii, they were overwhelmed in an instant. Watching from a hill as the Trade Center burned, Stewart Manville, a resident of White Plains, tells how he imagined the reactions of the people of Naples as they watched the extinction of Pompeii and its inhabitants by Vesuvius in 79 A.D. The sudden altering of the familiar skyline, and the attendant feelings of disorientation reminded others of a more recent volcanic event, the eruption of Mt. St. Helens. In our misplaced confidence in technological achievement, we can compare the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, also resulting in the loss of bright young lives. As a sneak attack, for which America should have been prepared, the assault seemed to many a replay of the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

Apocalyptic in its sudden, fiery destructiveness, the ruin of the Twin Towers opened enormous black holes in the sides of the giant buildings, chasms into visions of Hell. Photographs of the burning towers, many posted on the World Wide Web, showed what seemed to be devil faces in the smoke. The fires burned for weeks; combined with search lights of rescue workers, they cast a hellish illumination by night on the Manhattan sky. To some, the comparison to the Apocalypse was more than a metaphor. Many bodies of those who died were never found, vaporized by the intense heat of the burning jet fuel. Their disappearance was eerily reminiscent of the belief of some in the Rapture, in which the elect, at the end of the world, are taken bodily up to God, leaving others to endure the reign of the Antichrist. One Web newsletter, addressed to believers in the literalness of Revelation, cautioned that "This is NOT the rapture. If you are still here that doesn't mean that you have been left behind... Jesus hasn't come yet. Also this is NOT the tribulation. It might sound like it, but it is not. Don't expect the Antichrist to address the world..."

Some 2800 people died at the World Trade Center. Yet there have been other disasters where the loss of life approached or exceeded that number, but they have not held our attention, because they were not centrally located or were not important to the myth of who we are and what we think we are about as a people. The burning and sinking of the General Slocum in 1904 is seldom mentioned now, although 1,021 died, mostly German Lutheran women and children from Brooklyn. Neither the disaster (in the East River) nor the memorial is centrally located. We remember the Titanic, but we forget the Empress of Ireland, which sank in the St. Lawrence River in 1914 with 1,012 dead. The Johnstown Flood devastated that Pennsylvania city the day after Memorial Day, 1889, killing 2209. In New York, 11,500 patriots died of starvation and torture under British occupation during the American Revolution. Ninety-three died in the Malbone Street wreck in Brooklyn of 1918, the worst rapid transit disaster in U.S. history. Forty died in 1920 in the anarchist bombing of the Morgan Bank. Six were killed and 1042 injured in the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center. We are devastated by the September 11, 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, but quickly forget the attack on the Pentagon which took place the same day; to be sure, there was less loss of life, but it was also less central to the myth. Some six months after the attacks of September 11, in March, 2002, almost 2000 were killed in an earthquake in Afghanistan, the unlucky country which terrorist leader Osama bin Laden exploited as his base of operations. It is a sad fact of American narcissism that public emotions remain largely unmoved by casualties from earthquakes, monsoons, massacres, and other catastrophes in less industrialized parts of the world.

Killing a landmark

The Twin Towers were a symbol of American power, as Osama bin Laden, in his twisted act of hommage and perverted lust, well recognized. Bin Laden wanted to destroy holy places even more than he wanted to kill people, as his choice of other targets demonstrates. With his background in the construction business, the terrorist Svengali made symbolic structures his targets, wanting to destroy the Eiffel Tower, symbol of France, though it contains few people, and Big Ben in London. He understood better than we what is sacred in our culture; not the "religion of real estate" or "greed," as some critics say, but our spirit and vigor, our reaching for transcendence, our exuberant optimism, our sometimes naive reverence for untrammeled individual freedom. His anger at the U.S. was sparked by fury at infidels being in Saudi Arabia, where the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina are. The Taliban, bin Laden's Islamic fundamentalist protectors in Afghanistan, in a similar act, destroyed the lofty twin Buddha statues in Bamiyan.

The Woolworth Building was called the "Cathedral of Commerce," partly because of its Gothic-inspired architecture, but the World Trade Center could have been described by that term.

Sacred relics and holy pictures

We search for holy relics of the martyred buildings, even as workers

search for remains and artifacts of the people who inhabited them.

"Saints' pictures" of the Towers are bought from vendors on the street,

like the holy pictures and medals for sale at the great religious

shrines. Unfortunately, civil authorities and "victims' rights

representatives" have loudly characterized these artifacts as "trivial

souvenirs" and their earnest buyers, seeking to connect with a profound

event, as somehow dishonorable. The desire of many to attain an even

greater nearness by possessing an actual piece of the buildings

themselves, even the smallest relic of their steel bones or aluminum

skin, has for the most part been thwarted by the same official guardians

of the site.

The World Trade Center as a sacred crystal, in a shop window on

42nd Street; click on picture to see entire window (photo by

C.A.Sowa)

Roadside shrines immediately sprang up, dedicated both to the people

and to the buildings, on walls, fences, and doorsteps decorated with

pictures, poems, candles and flowers. Memorials were

created, like the storefront mural shown below, on the wall of a

Chinese restaurant on Houston Street, depicting the Twin Towers

with angel wings and halo, surrounded by floating peace symbols. The

globe of the Earth in the sky marks the location as Heaven, where the

Trade Center has other heavenly buildings as companions.

The World Trade Center apotheosized: mural on a storefront, showing the Towers in Heaven with wings, halo, and peace symbols; click on picture to see entire storefront (photo by C.A.Sowa)

Organized religion has played a role, too. After September 11, there was a temporary gain in church attendance. A "cross" formed by steel beams was seen in the rubble, and, not surprisingly, was deemed miraculous, since at that point to find anything intact seemed improbable. On Good Friday 2002, a procession carrying a cross made its way from a church in Brooklyn across the Brooklyn Bridge to the World Trade Center site, led by a fireman, in recognition of the heroic role of the Fire Department, which lost many members in the disaster.

Rival cults: Ultra-patriotism, Grief, and Progress

As usual, there are competing cults. A large impediment to our recognition of the psychic value of the sacred city and the urban landmark, as I wrote in "Holy Places," is the rival national cult of America and her icon the Flag, a worthy cult but nurtured in a pastoral myth of creating a new Eden. In the days after the attack, the emphasis quickly shifted in official government propaganda from an "attack on New York and Washington" into an "attack on America." Of course, Osama bin Laden did mean his attack on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon (and possibly an aborted attack on the Capitol or the White House) as an affront to terrorize America. We note, however, that he attacked her cities and her skyscrapers, not her cornfields. Perhaps it was necessary to emphasize the aspect of the "attack on America" to persuade the rest of the country, including its traditionally anti-urban (and specifically anti-New York) population, to join in the military campaign against Osama and his latter-day pirates. Oddly congruent, however, with this shift in emphasis was what seemed to be a campaign--almost a conspiracy--to erase the image of the Towers from memory; pictures of the pre-disaster Towers were made to practically disappear, erased from skylines in soon-to-be-released movies and from the backgrounds of advertisements. Mayor Giuliani attempted (fortunately without success) to prevent street vendors from selling photographs or souvenirs of the Towers. There was a misguided effort to keep people from viewing the site at all; ridiculously, the mayor even ordered the police to arrest anyone taking a picture of the fallen towers. The display of American flags, flag pins, and red-white-and-blue memorial ribbons, however, became de rigeur. (A compromise, though harder to find, was the combination pin, T-shirt, or poster showing both the flag and the towers.)

The cult of Grief has blossomed, represented by images of the towers' destruction, of the empty skyline, or by a lugubrious succession of plans for a giant memorial. The smoking towers, with black holes of hell on their sides, are obsessed over and made the subject of TV specials, with the excuse that they celebrate the (undeniable) bravery of fire, police, and other rescue workers who died. There is a desire by some of the families of those killed to make the entire site a memorial, despite opposition from residents of the neighborhood and merchants who desperately want to return the place to its rightful function as a thriving trade district. Grief is fetishized, and appeals are made to create a mawkish grief garden modeled on the one erected in Oklahoma City after its Federal Building was bombed. "Victims" and their families have been elevated to celebrity sainthood, like JFK, Diana, and JFK Jr. Legitimate claims for sympathy by survivors, by kin of those who died, and by those who lost jobs, places of work, and customers in the attack are overwhelmed by what Mark Twain, in Huckleberry Finn, called Tears and Flapdoodle. The public face of an event that began as Aeschylean high tragedy has ended as Euripidean melodrama, like The Trojan Women or Hecuba, complete with a chorus of weeping widows and children.

Another rival cult to our reverence for our buildings, as I pointed out in "Holy Places," is Progress, a stern Moloch who demands that everything we make or build must be new, different, and Up-To-Date. Unlike the Japanese, who are unembarrassed at reerecting the Temple of the Golden Pavilion when it was burned down by a fanatic, Americans feel that there is something morally wrong at rebuilding an exact copy (or even a modified copy, with stronger structure) of Penn Station or the World Trade Center. Anything built must express "the new spirit of the age," or some architect's new private vision, or some newly fashionable art theory. Perhaps one reason for what seemed to be an officially sanctioned attempt to erase the image of the towers from depictions of the skyline and for discouraging ordinary people from visiting the site may have been to erase their memory so that real estate and government planners would not encounter as much opposition to putting up something different.

Since at this writing, the current leaseholder, Larry Silverstein, and the Lower Manhattan Redevelopment Authority seem unwilling to put up another tall building (partly out of legimate fear of another terrorist attack) we are in danger of losing the Towers twice, once to terrorists, a second time to the same real estate interests who destroyed the small stores of Radio Row to build the Trade Center and who earlier destroyed Pennsylvania Station, or to the "grief lobby" who want to turn the entire site into a memorial.

It is an irony that many landmarks built by robber barons (like Grand Central Terminal), are now loved by the public. What they put up is beyond our control, but we grow to love it, and it matters to us when it is destroyed. As of this writing, the local Community Board of lower Manhattan is struggling to have some say in what happens in the rebuilding of the Trade Center.

Rebuilding the World Trade Center: still a Holy Place

Life renews itself. Like the ailanthus, forcing its way strongly between the sidewalk cracks of every New York street, the striving spirit returns to the sacred site. Following the destruction of the World Trade Center in 2001, the site is said to be "hallowed" because it is a "mass grave," presumably an exaggerated reference to the fact that many of the dead were never found, although in point of fact, the site is being excavated down to bedrock. As we have seen, the site was already a holy place, and this horrific event only enhances its meaning as a sacred place. With so many elements contributing to the mana of the place, it is, in the language of the social sciences, an "overdetermined" symbol. The "victims," unlike the nameless unremembered casualties of many other disasters, are saints because they died in a sacred place, not vice versa. Yet because so many were never found, we can indeed, if we believe in ghosts, think that their spirits haunt the place, along with the ghosts of many others that have lived and died there, the Dutch patroons and the English merchants, American patriots and African freemen and slaves, and before them, the Lenape Indians, living on their sacred island.

We must rebuild the stone in the mandala. A rebuilt World Trade Center, or whatever occupies the place, residential, cultural, or commercial, whether one tower or two, or something else, must express the centrality, the sense of place, the purposefulness, and the aspiration of the original, or it will not be satisfying. The Trade Center area must remain a hub of transportation, commerce, and communication, and now a growing residential neighborhood.

The happy vulgarity of the street vendors selling souvenirs at the site unconsciously recreates the original purpose of the original Port Authority planners of the Trade Center in the 1960's, who envisioned an image of a mediaeval street fair. Mercury, the god of commerce and communication, depicted over the façade of Grand Central Terminal, presides. According to the Times, the New York tourist industry is now using grief as a "marketing device," saying, in effect, "Come see our wounded city." I see this as healthy; they are making lemonade, as the saying goes, when life gives them lemons. New York exuberance and mercantile optimism cannot be kept down forever. Combined with traditional religion, prosperity and the ambition to prosper have been linked with godliness since early days of Puritan America. We should remember the World Trade Center as we loved it, in its beauty and youth, not in its death. As Dido sings in Purcell's Dido and Aeneas, "Remember me, but ah, forget my fate." Another scene comes to mind, from Ingmar Bergman's film The Seventh Seal: In a plague-ridden world, Death cuts down a tree in which a man is sitting; although the man pleads for his life, the tree falls and the man dies; a little squirrel jumps up on the stump, cheerily investigating it. Life regenerates. The people who died in the World Trade Center were happily in business to make money. The best memorial is to build a place to do more business. Its middle name was "Trade," after all.

The World Trade Center site is valuable, not just as real estate, but

mythically. New York is a place where one can reinvent oneself, and the

city itself is constantly reinvented.

The World Trade Center revived: Mercury rules as street vendors

pursue the business of trade on a corner of lower Broadway

(photo by C.A. Sowa)

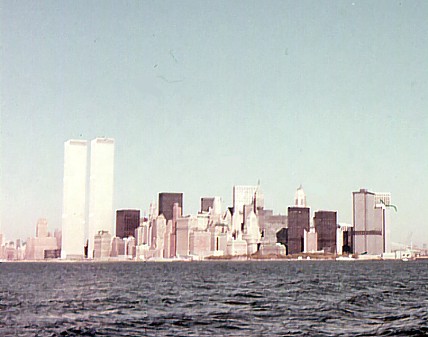

New York, the mythic gateway (photo by C.A.Sowa)

Copyright © 2002, Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Number:

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.