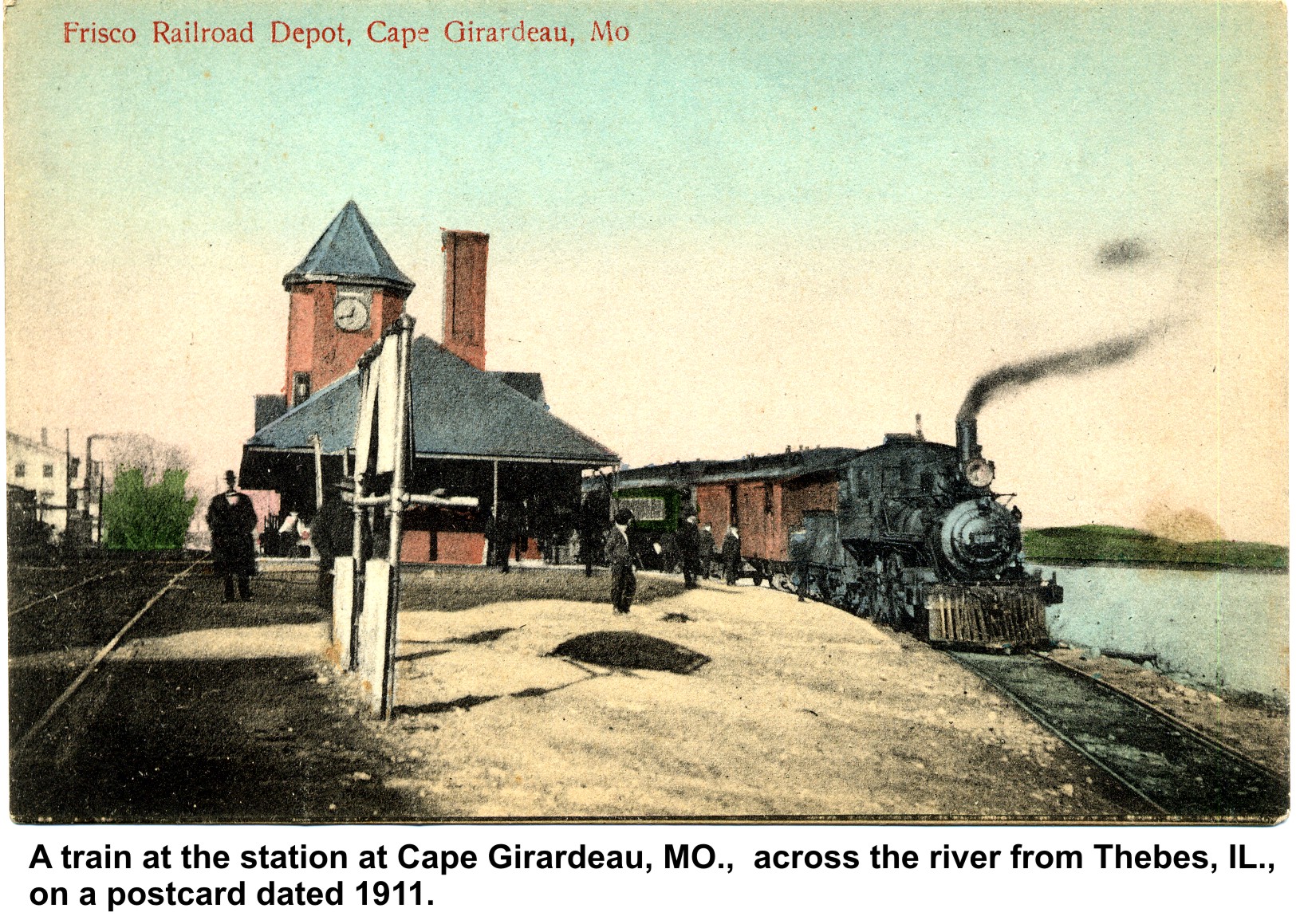

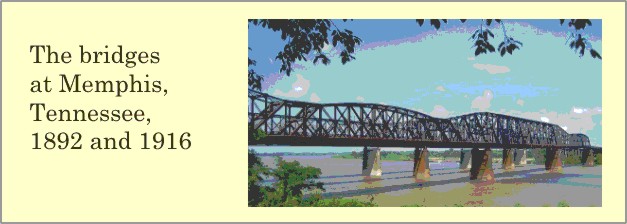

The bridges over the Mississippi at Memphis, Tennessee

Of the four bridges over the Mississippi at Memphis, the two oldest, the

"Frisco" bridge (1892) and the Harahan (1916) carry railroad traffic, the

two youngest carry automobiles (on Interstates 40 and 55).

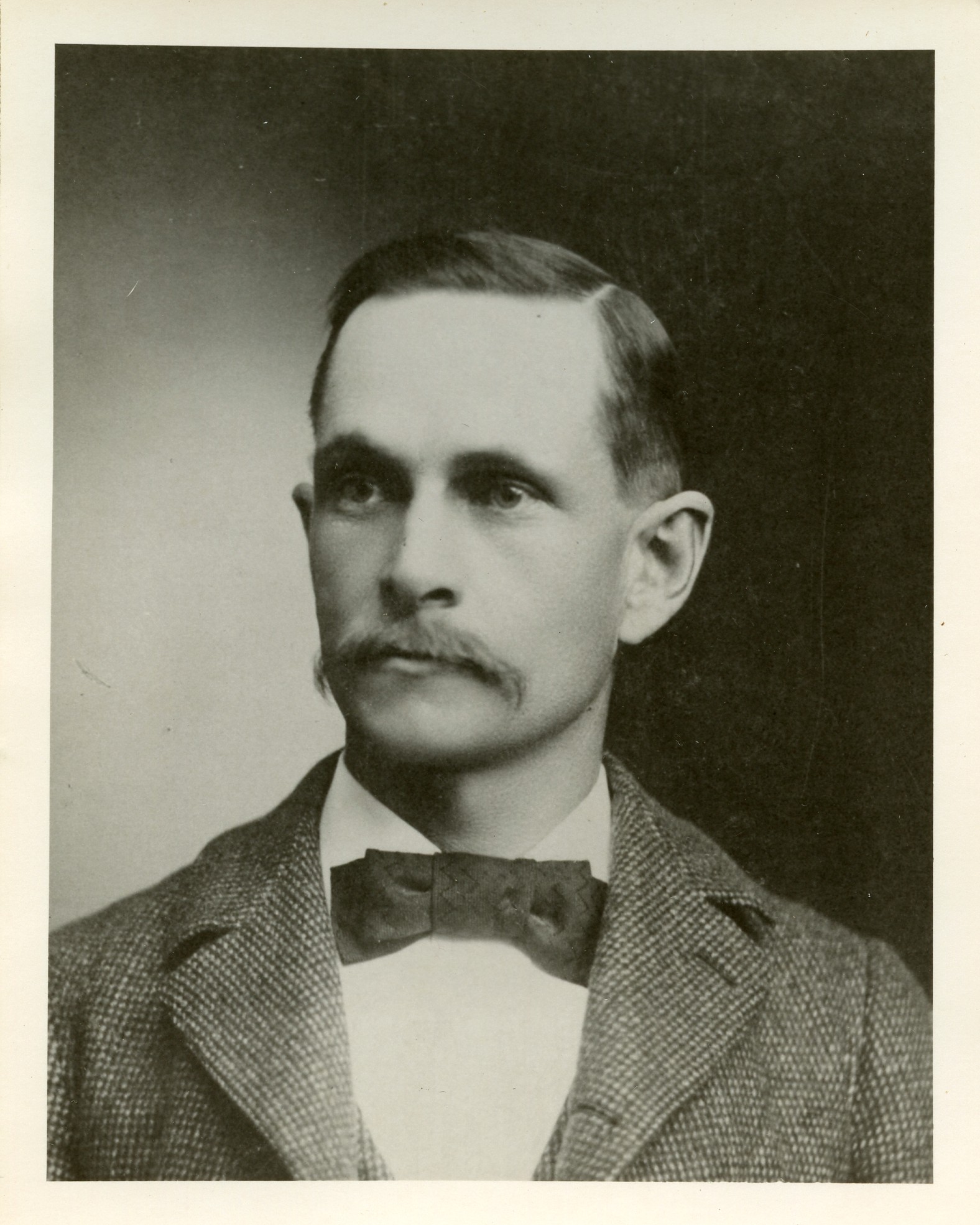

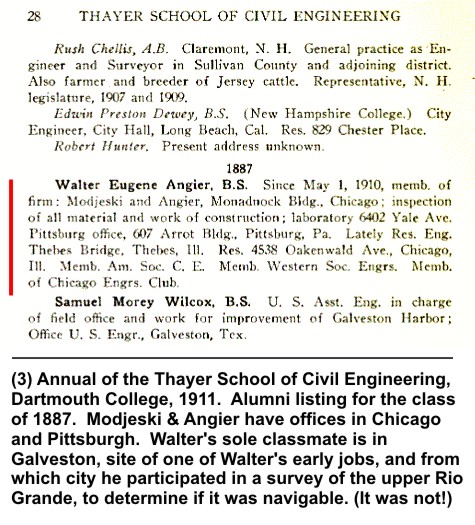

Walter Angier, working first for George Morison and Alfred Noble on behalf of the

Kansas City and Memphis Railway and Bridge Company, then with Ralph Modjeski,

was an engineer on both of the railroad bridges.

The I-55, Frisco, and Harahan bridges, while having quite different truss

shapes, are so close together, with the Frisco sandwiched between the other

two, that they can almost look like a single bridge, as can be seen in the

photos at the bottom of this section. The effect is enhanced by

the fact that the piers of the later bridges are exactly aligned with the

older structure, to facilitate navigation, Recently there

was word that a new bridge, for both trains and automobiles, may be built.

The pictures of both bridges that appear below were taken by me in 2011.

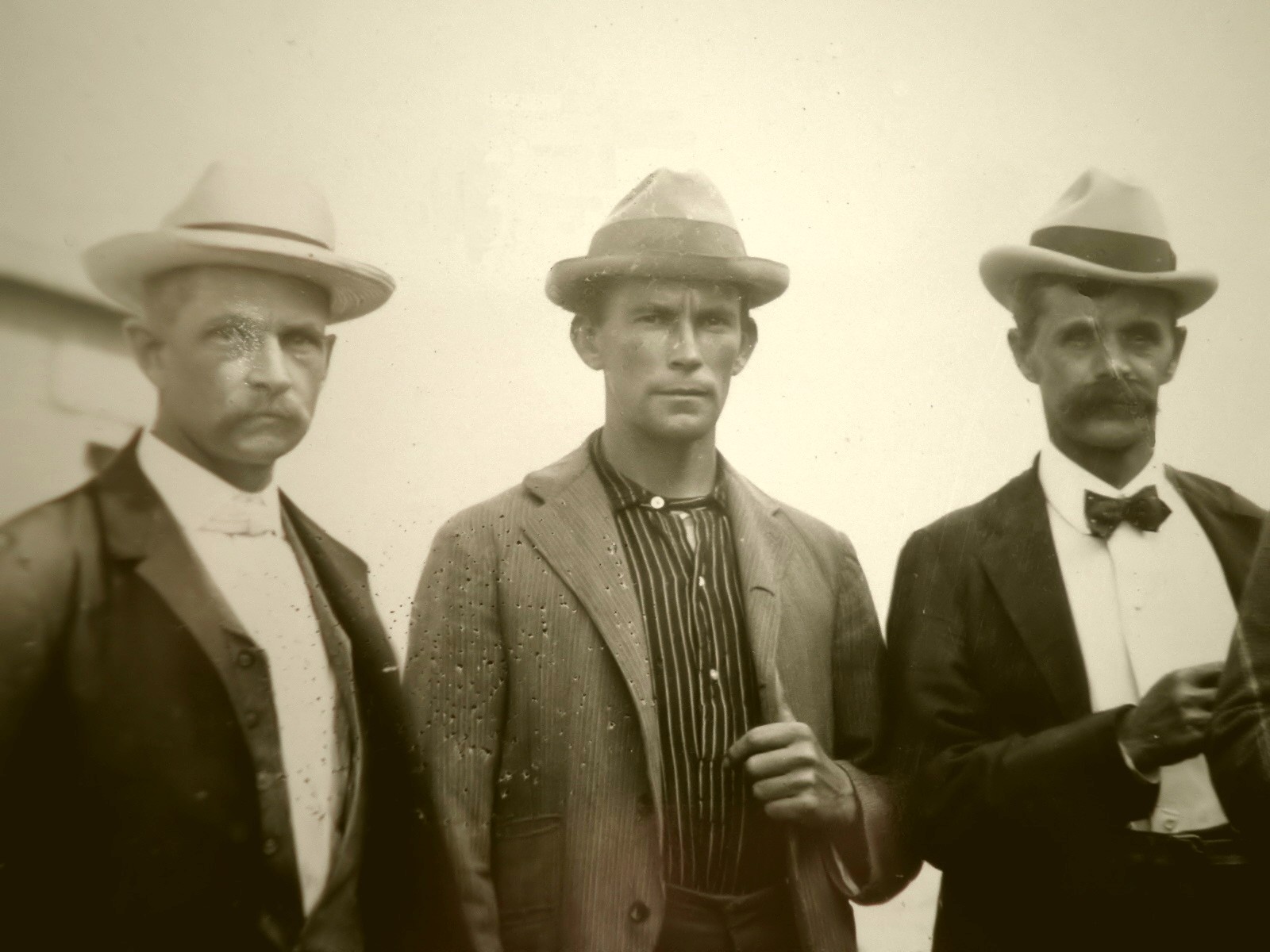

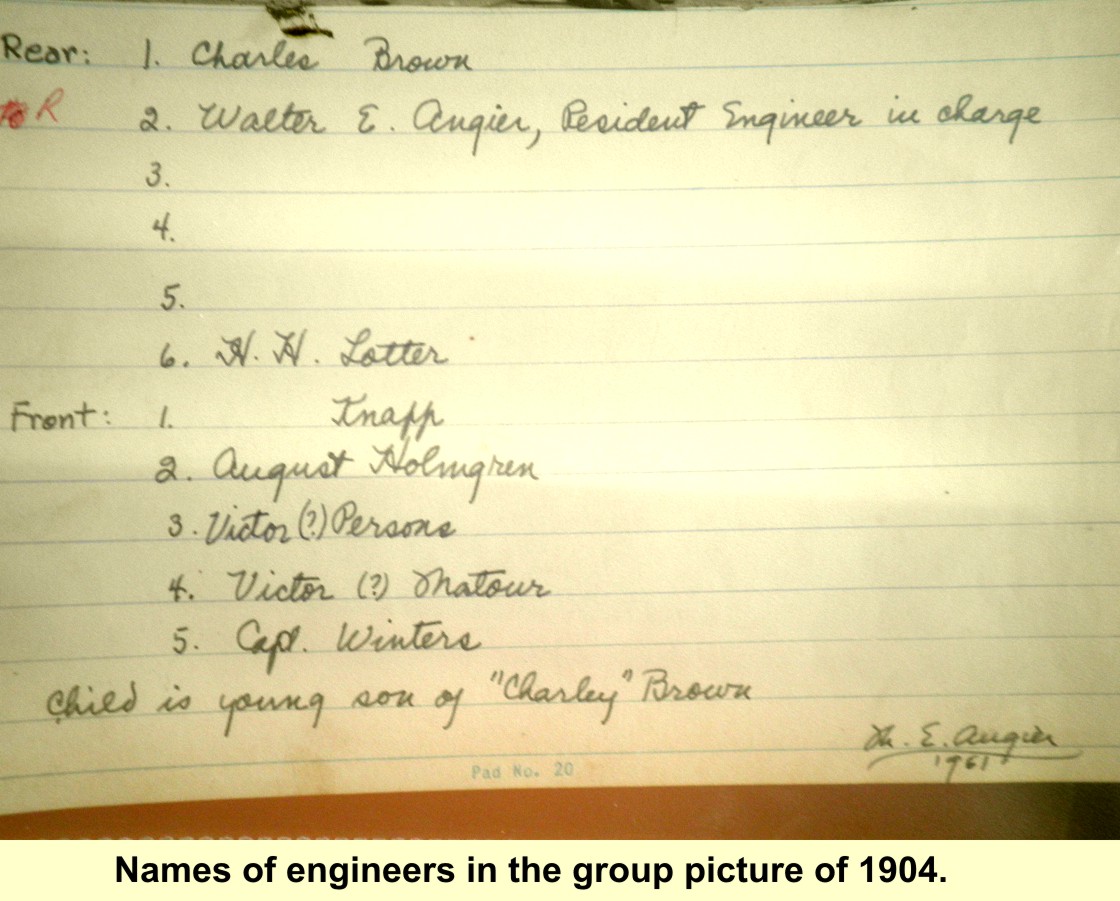

Photographs of the original construction, including group shots of Walter

Angier and the other engineers, donated by Estelle Angier, reside in the

archives of the Memphis Public Library and Information Center, They can be

seen online at their

Dig Memphis Web site.

The "Frisco" Bridge, 1892

The first bridge at Memphis, opened on May 12, 1892, was the occasion of

great civic pride and enormous public celebration, being the first bridge

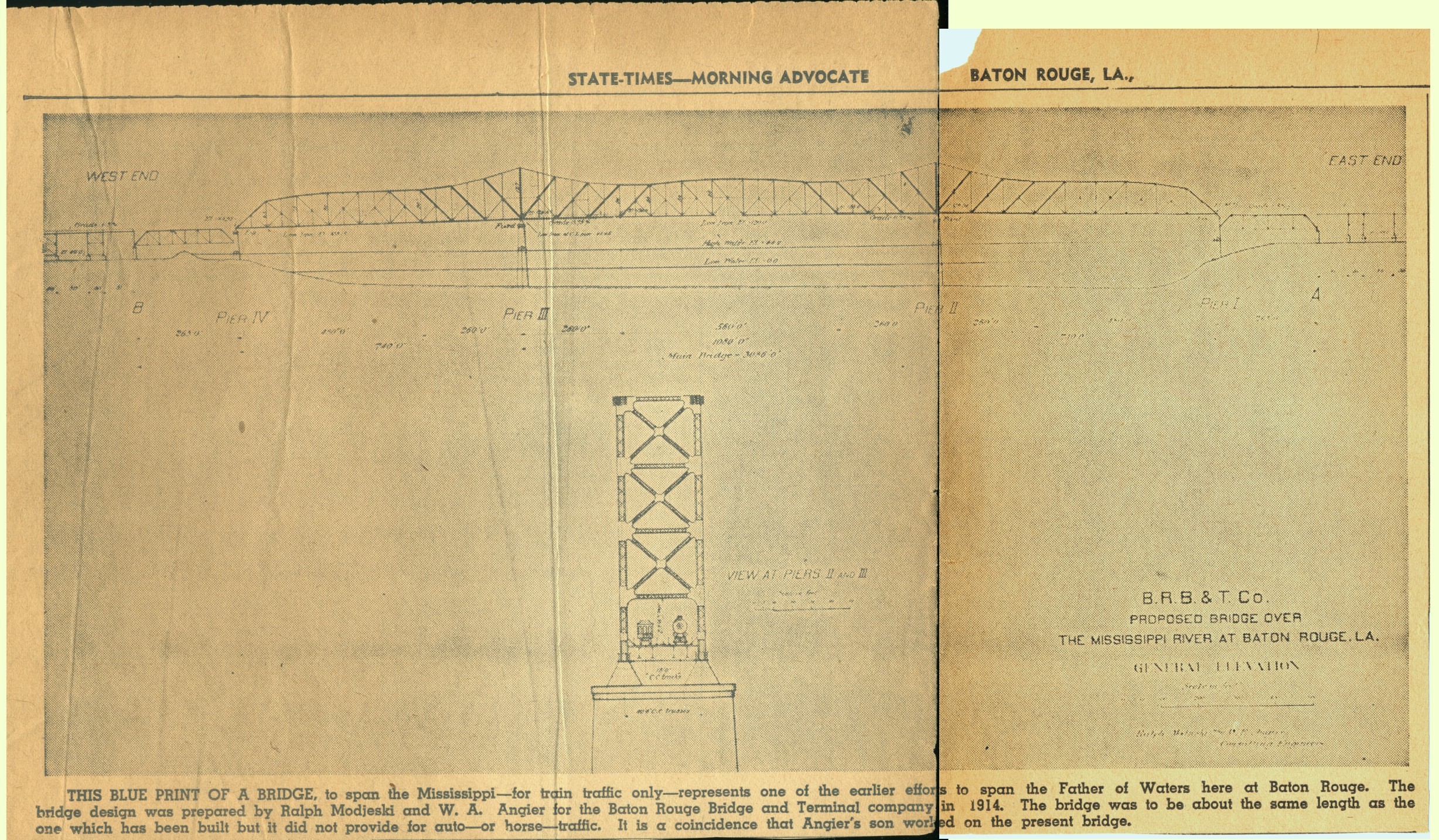

across the Mississippi so far down river (of course, many years later,

bridges were to be built much farther south, in

Baton Rouge and New Orleans).

The Kansas City, Fort Scott, and Memphis Railroad, of which the Kansas City

and Memphis Railway and Bridge Company was a subsidiary, later was bought by

the Saint Louis and San Francisco Railroad or "Frisco" (which a few

mergers later became part of BNSF, which still uses the bridge), hence the

name by which it is now known. It was built to carry trains, but had a wide

enough deck to accommodate buggies and, later, automobiles, if no train was on

the span. It now carries only rail traffic (single track).

Walter Angier and Ralph Modjeski were both employed on the

"Great Bridge at Memphis," as it was originally known, before they

went into partnership with each other. The bridge was principally

the work of George S. Morison, a celebrated

bridge designer of his day, a pioneer in the building of bridges of

open-hearth steel, which was replacing stone and wrought iron as a

structural material at the time. Morison served on the

Isthmus Canal Commission, where he was influential in changing the minds

of decision makers (including Theodore Roosevelt) to locate the canal in

Panama instead of Nicaragua. Walter Angier was invited, as his daughter,

my Aunt Estelle, told me in a letter in 1973,

to work on the Panama Canal, but "Mama wouldn't let him go"!

The New York Times reported the festivities attending the

opening of the bridge, under the title

"Memphis's Great Bridge" (available from the Times web site).

In addition to descriptions of the decorations and parades, the article

describes how, at a signal from engineer Morison, "a procession of

eighteen locomotives moved upon the bridge."

Senator Voorhees of Indiana delivered a lengthy and florid oration,

of which the Times provides excerpts. The article also

describes some of the structural details of the bridge, and tells

how, during excavation for the bridge piers some Spanish halberds from

the time of de Soto were unearthed. Voorhees predicted the building of

the Isthmus Canal, in which, as we know, Morison played an important part.

Later in the month, Railway World (May 21, 1892, vol.36, p. 485,

available from Google Books) published an almost identical article, with

only a few changes in expression, with the title

"The Memphis Bridge". It omits the excerpts from Senator Voorhees'

speech, and includes the interesting detail that the parade of "ponderous"

locomotives was performed "as the supreme test." In both articles, the

lengths of the individual spans don't add up to the total as given.

Parts of the Times's breathless coverage are reproduced below.

The Harahan Bridge, 1916

The Harahan Bridge, built for a consortium including the

Rock Island Railroad, was named for the former president of the

Illinois Central, who had died when his private railroad car was

rear-ended by another train (as reported in detail by the

NewYork Times.)

It was the design of Modjeski and Angier, now working together.

It was fitted in 1917 with rickety roadways suspended from both sides.

These were in use until the first real automobile bridge was built

in 1949. One of these roadways may be rebuilt as a pedestrian walkway.

It now carries trains of the Union Pacific (double track).

Walter Angier's work on both bridges at Memphis

made its way into the popular writing of its time. Julian Leonard Street,

journalist, playwright, and travel writer, published his American

Adventures: A Second Trip "Abroad at Home' in 1917. In Chapter L,

"Modern Memphis," he describes a visit to the second, or Harahan bridge,

then under construction (and his queasiness at walking out on the

half-finished structure). Paragraphs are excerpted below (quoted from the

Project Gutenberg eBook of American Adventures by Julian Street).

In these selections, "W.E. Angier, assistant chief engineer" on the

new bridge, is described as having found, during excavations for

the old, or "Frisco" bridge, "a Spanish halbert...thought [to] date from the

time of De Soto."

Street's queasiness upon the bridge was justified: a number of steelworkers

(some say as many as twenty-three) were in fact killed during its construction.

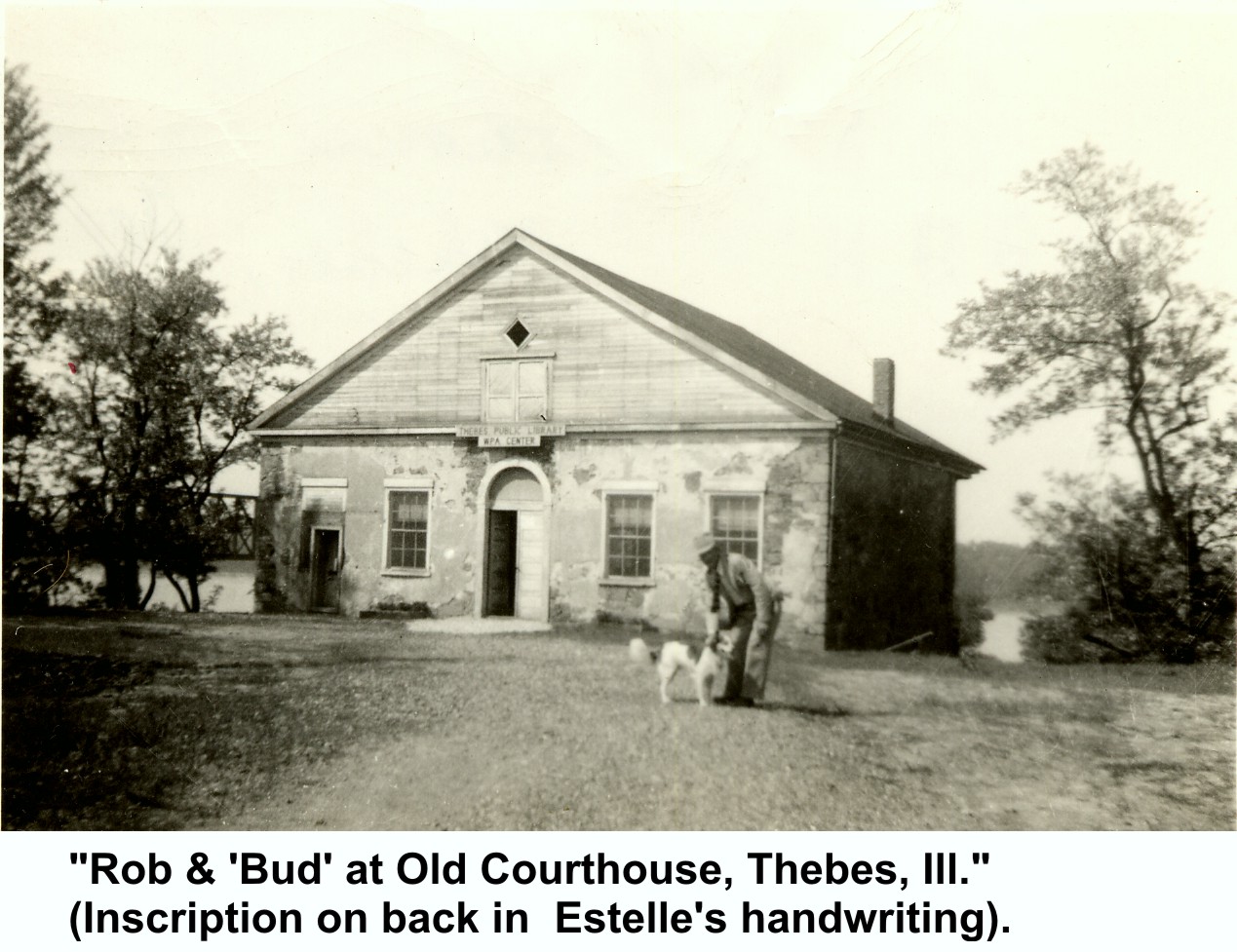

Dr. Robert Wood Mitchell of Memphis, for whom my father was named

Memphis was the home of Dr. Robert Wood Mitchell, physician, army

surgeon (in the Confederate Army), founder of the Memphis City Hospital,

a leader in the fight against yellow fever, advocate for the education of

female professional nurses, and pillar of the community. He was a

family friend of Mary Angier, and Aunt Estelle reported that she believed

that Walter and Mary lived with the Mitchells when they were in Memphis.

This would have been during the building of the first bridge.

They named their younger son, who grew up to be my father, after him,

Robert Mitchell Angier.

|