Minerva SystemsDr. Cora Angier Sowa |

CORA SOWA'S RIGHT-OF-WAY:RAILROAD (AND ENGINEERING) HISTORY OF CORA ANGIER SOWAPage 8Engineers in the Family, Part IIIRussian and American Life of Alexander Lodyguine, Russian Inventor and Engineer |

Minerva Systems

Dr. Cora Angier Sowa

CORA SOWA'S RIGHT-OF-WAY:

RAILROAD (AND ENGINEERING) HISTORY OF CORA ANGIER SOWA

Page 8

Engineers in the Family, Part III

Russian and American Life of Alexander Lodyguine, Russian Inventor and Engineer

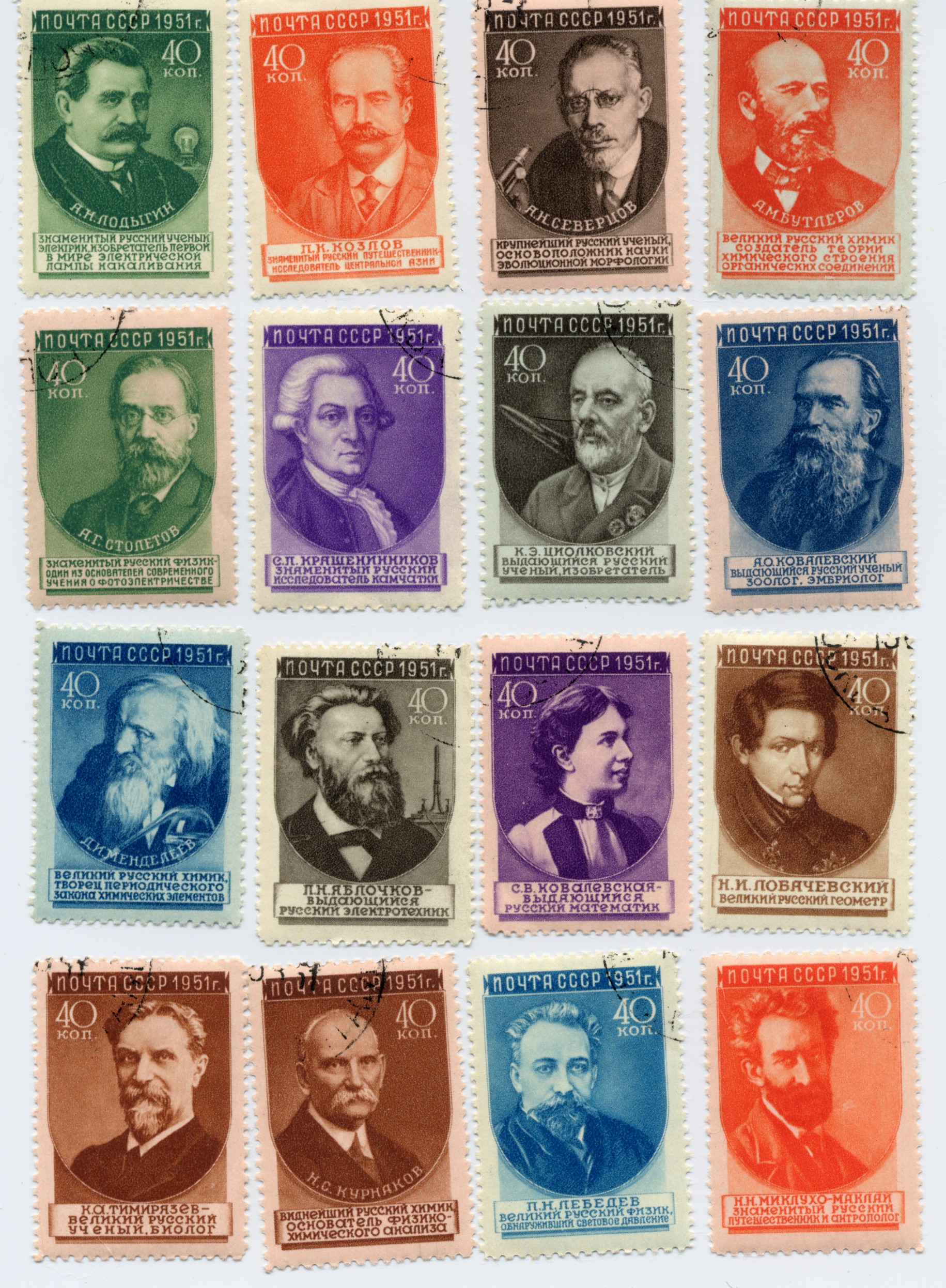

Alexander Lodyguine depicted on a 40 kopeck postage stamp of the USSR in 1951, honoring him as inventor of the electric light bulb. This was one of a set of sixteen Soviet stamps honoring Russian scientists, inventors, and mathematicians. (Note the picture of the light bulb he invented, on the right.)The title on the stamp says: "A.N. Lodygin, Famous Russian Electrical Engineer, Inventor of the World's First Incandescent Electric Lamp."

On previous pages of Cora Sowa's Right-of-Way, which is part of my Minerva Systems enterprise, I illustrated some of my connections to railroading, including travels with my father, Robert Mitchell Angier, Head Cost Analyst for the Los Angeles Division of the Southern Pacific, and my growing up in a house above the old Subway Tunnel in Los Angeles. On this page and the preceding pages, I chronicle other family members' connections to civil and electrical engineering, with more material from my personal archives. On the preceding pages, there are entries for my grandfather Walter Angier and my uncle Philip Angier, both civil engineers. On this page, I have put more material from the family archives concerning Alexander Lodyguine, Russian inventor and engineer, who was my mother's uncle by marriage.

To return to the Minerva Systems home page, click here.

To return to the first page of Cora Sowa's Right-of-Way (Railroad History), click here.

To return to Page 5, "Engineers in the Family I," click here.You can also contact me at casowa@aol.com.

Dr. Cora Angier Sowa

CONTENTS OF THIS PAGE:

- The Making of an Inventor (introduction to archival material about Alexander Lodyguine, my great-uncle by marriage)

- Alma Schmid de Lodyguine's memoir of Alexander Lodyguine, Part I, Chapter 1 (boyhood in feudal Russia, sympathy with serfs, early experiment with homemade airplane)

- Alma's memoir, Part I, Chapter 2 (Cadet school, interest in aviation, scientific research)

- Alma's memoir, Part I, Chapter 3 (University, quixotic attempt to help French Republic with his airplane plans)

- Alma's memoir, Part II (unfinished), (would have covered his early career, his move to America, his marriage to Alma, his return to Russia)

- Memoirs of Dr. Charles Cooper Vol. I, excerpts describe "Uncle Alexander" Lodyguine, his uncle by marriage, (how he met the Schmid family in Pittsburgh, recapitulation of Lodyguine's early life, his inventions, his career in America, birth of his and Alma's daughters)

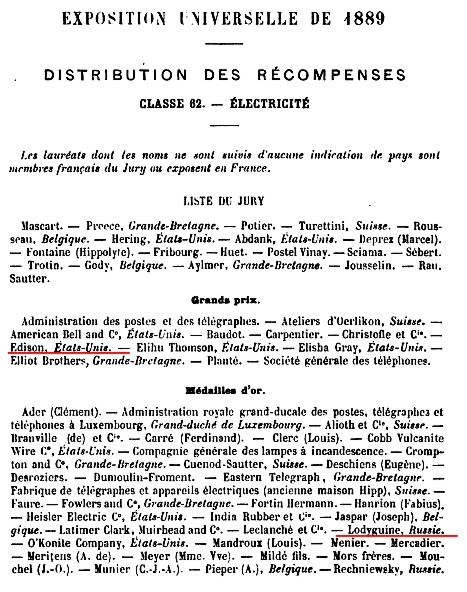

- Lodyguine's incandescent light exhibit at the Paris Exposition of 1889, for which he won a Gold Medal (note to Charles Cooper's memoirs, official descriptions of the exhibit, lists of prize winners)

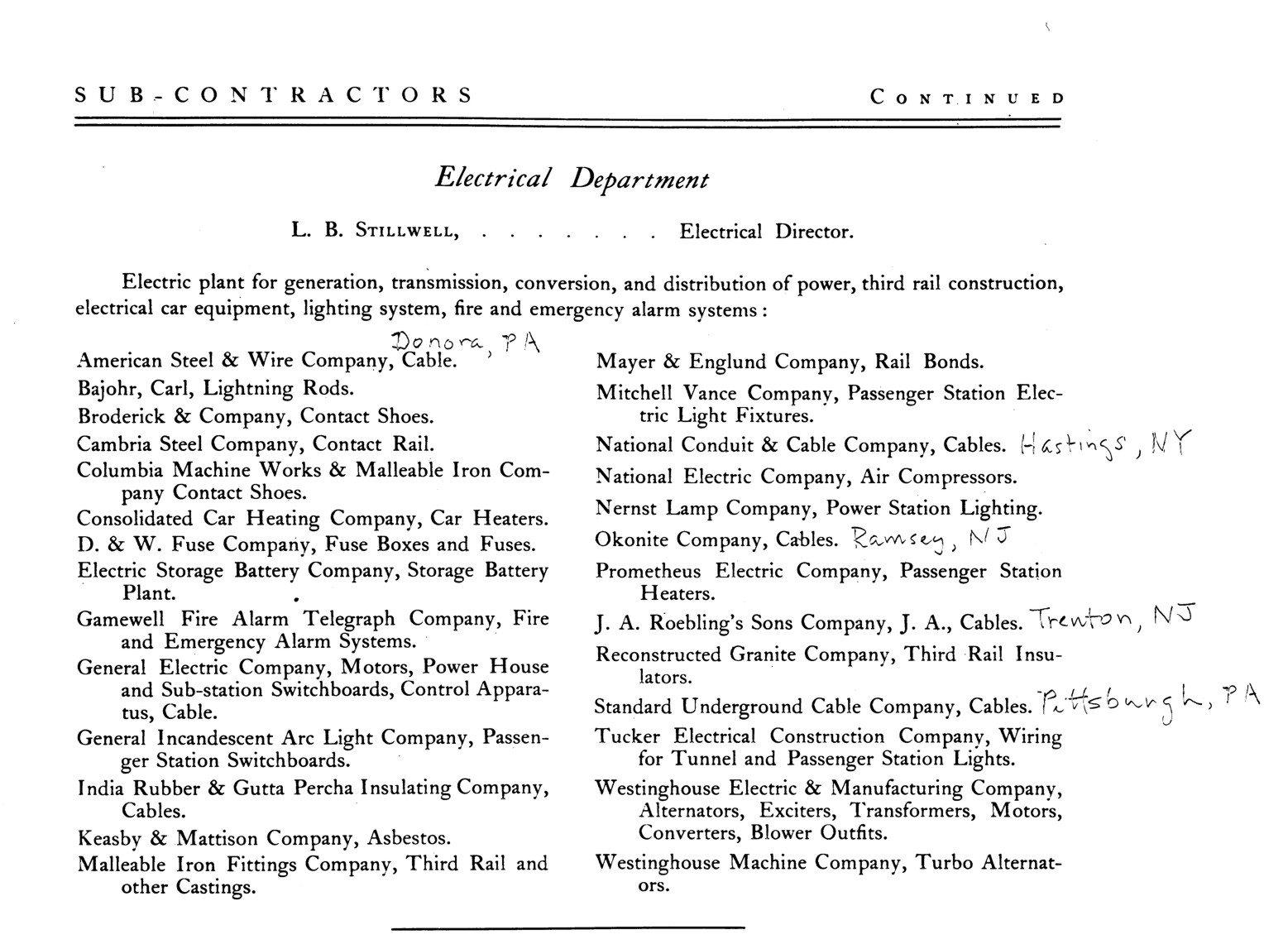

- Lodyguine's role in electrifying the New York Subway (note to Charles Cooper's memoirs, list of subway subcontractors)

- Memoirs of Charles Cooper Vol. II (excerpts describe Lodyguine's various jobs in the U.S., his return to Russia at end of czarist period, his role in developing the streetcar system for St. Petersburg)

- Alma's memoir, Part III (incomplete) (Lodyguine back in Russia in 1914, he refuses to deal with Rasputin; unwritten parts would have described downfall of Russia, his eventual return to America)

- Memoirs of Charles Cooper Vol. II, continued (excerpts describe World War I, Lodyguine's daughters play a role in the February Revolution, the Lodyguines escape to America ahead of the Bolsheviks)

- Interview in the New York Times (Alma Lodyguine and daughters give an interview upon their escape)

- Lodyguine's American family reconnects (family members (including myself) become better acquainted with Lodyguine's daughters)

- Memoirs of Charles Cooper Vol. III (excerpts describe Charles and Edris Cooper's visit to the Lodygin exhibit in Moscow)

- The next generation connects (my cousin Chuck and I make friends with Lodyguine's daughter Rita Faust)

- Who Invented the Electric Light Bulb?

- Grave of Alexander Lodyguine and his younger daughter Vera in The Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn

- Series of Soviet stamps honoring Russian scientists and inventors (including Lodyguine)

- Family tree (abbreviated, shows important relationships)

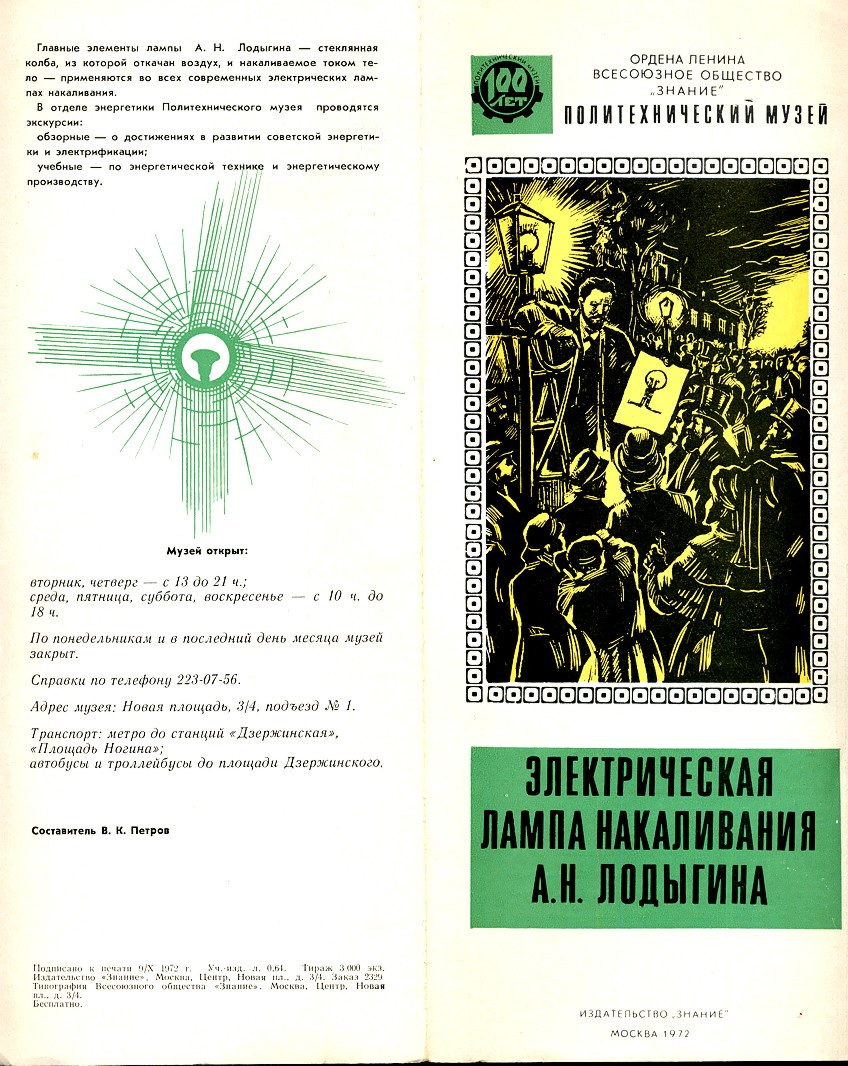

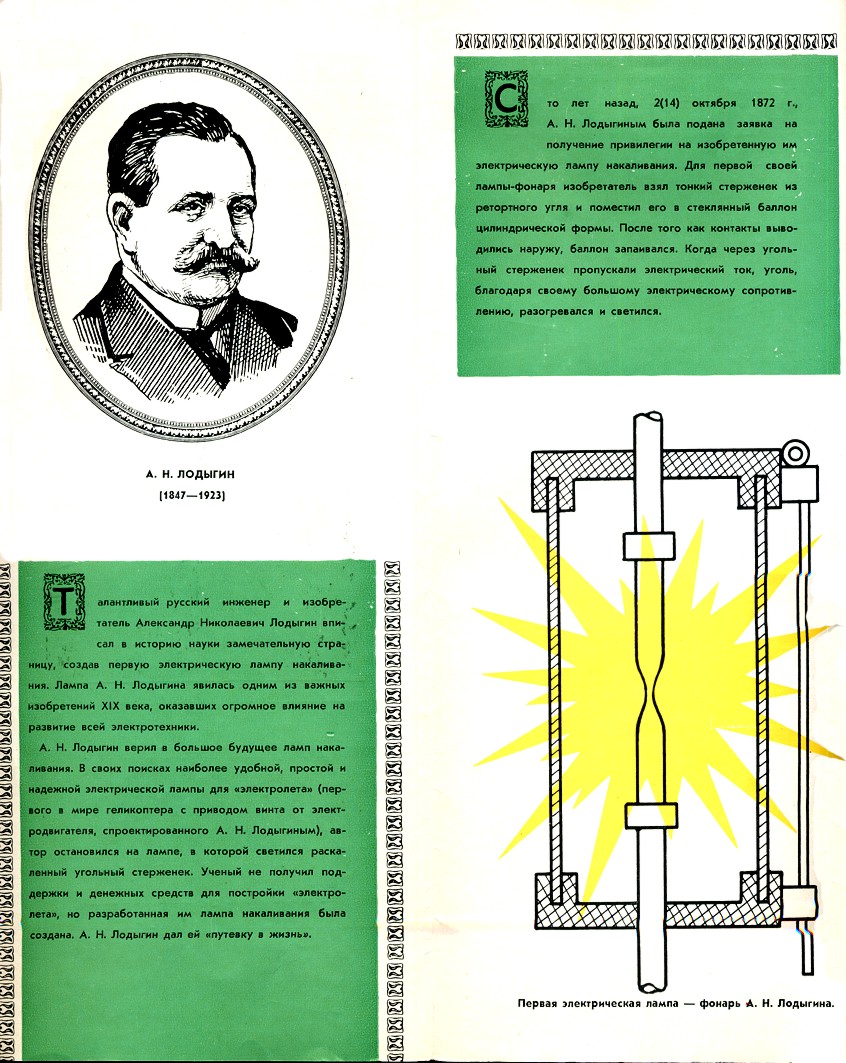

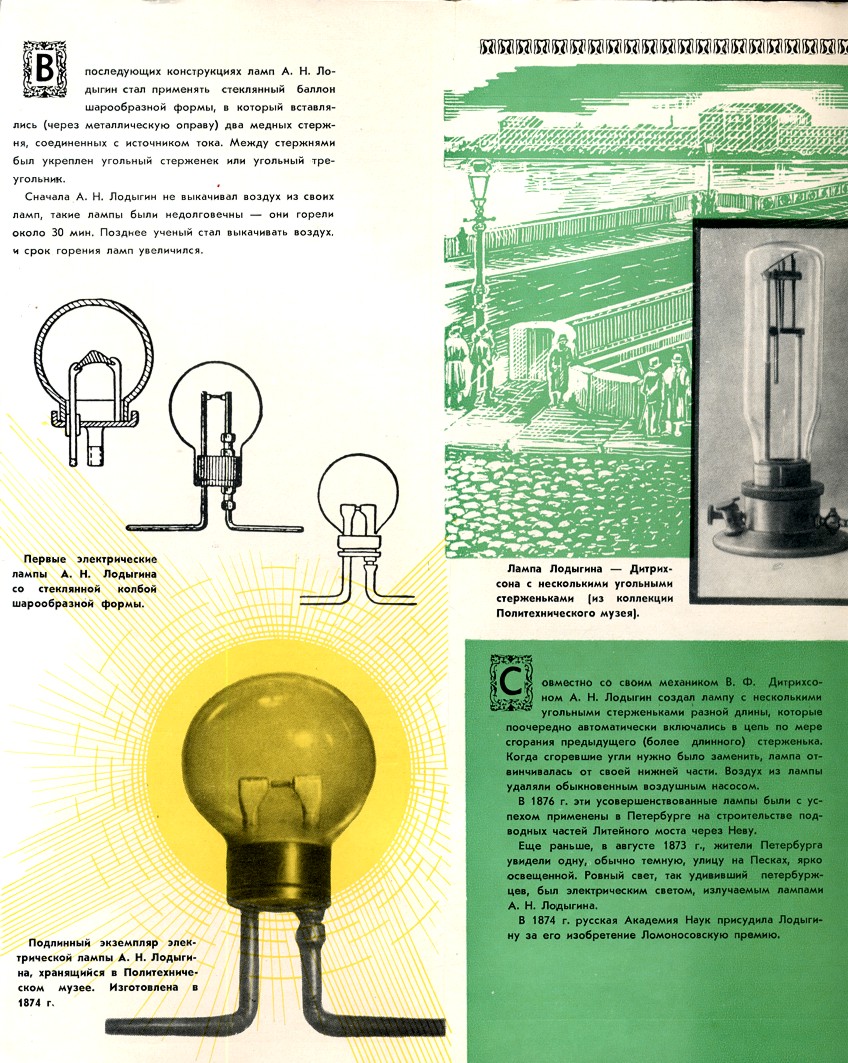

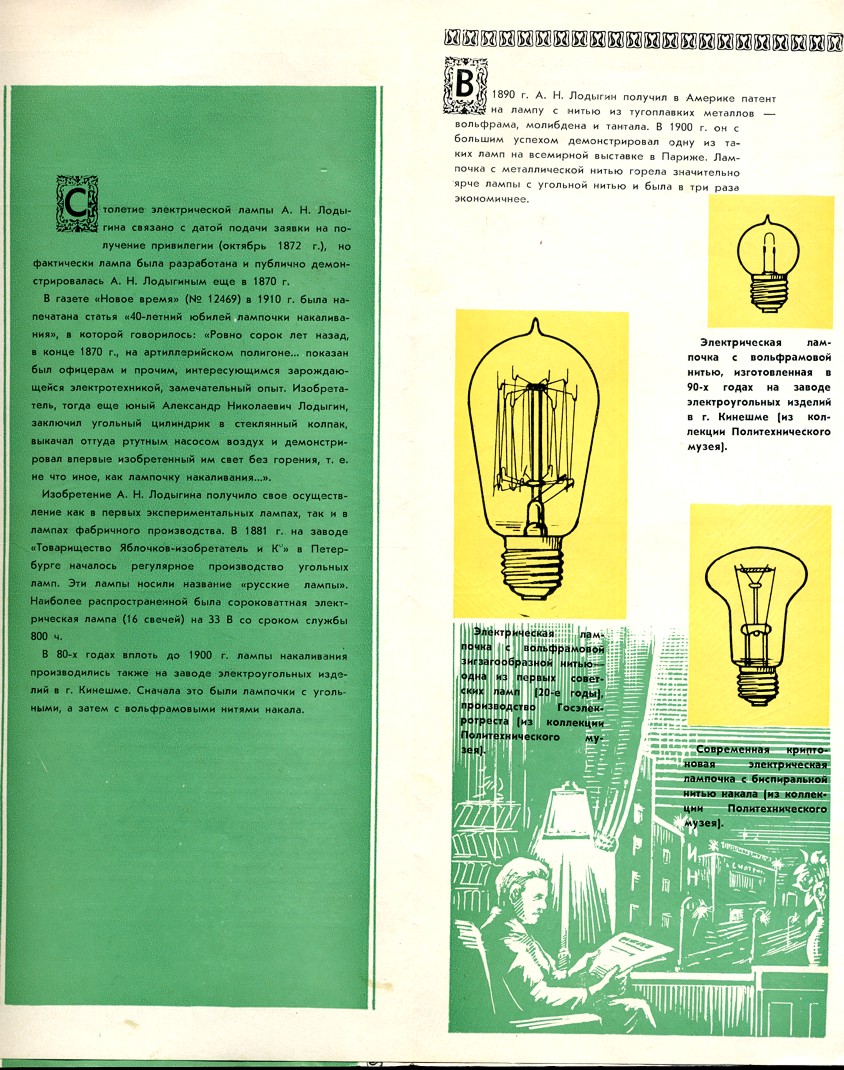

- Souvenir pamphlet from the Moscow Polytechnic Museum (honoring the hundredth anniversary of Lodygin's lamp, 1972)

The making of an inventor

An intercontinental life

Alexander Lodyguine (Russian: Lodygin), Russian inventor and electrical engineer, was married to Alma Schmid, my mother's Aunt Alma, sister of my grandmother Virginia Schmid Cooper, the California landscape painter. While he is little known in the United States, he is famous in Russia as the inventor of the light bulb, an invention that made him a rival of Edison. He experimented with various types of incandescent lamps, using tungsten and other materials. A bulb of his invention was exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1889. He was also obsessed with developing an early airplane. Born and raised in an aristocratic family in czarist Russia (but with plebeian sympathies), he spent many years in America. In Pittsburgh, he worked for Westinghouse and other employers. It was in Pittsburgh that Alma, a teacher, lived with her family, in whose home Lodyguine rented a room. Alma's father (my great-grandfather) was a schoolmaster who had emigrated to the U.S. from Bavaria in 1867.

Alexander first flirted with Alma's sister Virginia ("Jeannie," who would marry someone else and become my grandmother — there were four Schmid girls in all). But later, in Paris, Alexander and Alma fell in love.

In the U.S. again, by now married to Alma, Lodyguine held a number of jobs. In New York, he supervised manufacture and installation of electrical wiring for the then-new subway system (1904). Back in Russia at the end of the czarist regime and during the ill-fated revolution that overthrew it (which in turn was overthrown by the Bolshevik revolution), he was in charge of the substations for the then-new St. Petersburg streetcars. Barely escaping with his family after the Bolshevik takeover, he returned to America. He died in Brooklyn. He is buried in The Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn.

Alexander and Alma had two daughters, Margarita and Vera (named for revolutionary Vera Zasulich). Neither daughter had children.

In present-day Russia, there is a display of his work in the Polytechnical Museum in Moscow, and a museum in his honor in his hometown in the district of Tambov, Russia. In the U.S., one of Lodyguine's lamps is in the William J. Hammer Historical Collection of Incandescent Electric Lamps. (William J. Hammer was a colleague of Thomas Edison.) This collection, when last heard from, was in storage at the Henry Ford Museum (The Edison Institute) in Dearborn, Michigan.

Lodyguine was depicted on a 40 kopeck postage stamp of the USSR (shown above) in 1951, honoring him as inventor of the electric light bulb. This was one of a set of sixteen Soviet stamps honoring Russian scientists, inventors, and mathematicians. (Note the picture of the light bulb he invented, on the right of the stamp.) The title on the stamp says: "A.N. Lodygin, Famous Russian Electrical Engineer, Inventor of the World's First Incandescent Electric Lamp." His daughter Margarita (my mother's cousin Rita) complained that the Soviets made him look like Stalin!

American memoirs, by members of Lodyguine's American family

Alma left an unfinished biography of her husband, written in 1923. It is reproduced below, supplemented by excerpts from the memoirs of my mother's brother, Dr. Charles William Cooper, my Uncle Charlie, who was Aunt Alma's nephew, and by an outline of an article by Lodyguine's daughter, Rita, which provides more information about the Soviet stamp.

Alma's story begins with little Sasha's boyhood in czarist Russia during the Crimean War (1854). The Lodyguines were of the old landed aristocracy (hence the family use of the name "de Lodyguine"). As a Classicist, I am struck by how the descriptions of feudal society, with the rich landlords making war and going on hunting parties (and trading vodka for land to increase their holdings!) and women serfs in the back room spinning and weaving, could have stepped out of Homer's Odyssey, with its descriptions of Nestor's or Odysseus' or Alcinuous' court.

Russian memoirs, by present-day members of Lodyguine's Russian family

Lodyguine's two daughters, Margarita and Vera had no children. However, descendants of his sister Yulia, many of whom also have become scientists and inventors, still live in Russia. Yulia's great-grandson Cyril M. Petrov, Professor of Geography and Geoecology at St. Petersburg State University, published a memoir of his family in the Journal of the University in 2006. This memoir is online at http://journal.spbu.ru/2006/06/13.shtml in Russian. A rough translation in English is available in Google. It supplies more details of Lodyguine's life and family heritage, as well as the further adventures and careers of Yulia's descendants, including a great-great-grandson, Oleg I. Korablev, deputy director of the Russian Space Research Institute.

One of Alexander's early forays into aviation, as recounted by Alma, consisted of fitting home-made wings on his sister Yulia and pushing her off the roof so that she would fly. Yulia didn't take off as planned, and survived with only a turned ankle. It appears that the incident was handed down as a family yarn by Yulia's descendants, who were always skeptical of its veracity. I was glad to be able to provide evidence of the truth of the story.

Who invented the incandescent light bulb?

The question of who first invented the incandescent light bulb continues to interest historians of science. Lodyguine and Edison were far from the only inventors addressing the problem, which was the subject of experimentation by many inventors from many countries over many decades. A discussion of this topic can be found farther down on this page. Today, the debate itself begins to seem quaint, as the incandescent bulb itself recedes into history, replaced by other technologies, such as the light-emitting diode. Who knows what will come next!

Alma Schmid, wife of Alexander Lodyguine (my mother's Aunt Alma), as a young woman. The Schmids were a German-American family living in Pittsburgh. Her father, Francis Xavier Schmid, was a schoolmaster and private tutor. Alma herself was by profession a teacher.

ALMA DE LODYGUINE'S STORY OF HER HUSBAND ALEXANDER NIKOLAEVITCH DE LODYGUINE BEGINS WITH HIS BOYHOOD IN FEUDAL RUSSIA. IT IS 1854, AND THE CRIMEAN WAR IS GOING ON. THE STORY OF A BRILLIANT RUSSIAN

by

AN AMERICAN WOMAN[The (early) life of inventor Alexander Nikolaevitch de Lodyguine

by Alma Theodora Schmid de Lodyguine.

Only the first chapters were written; the rest exist as titles only.

All of Alma's original footnotes are provided as endnotes following Part I of her narrative.]Part I

Chapter 1

It is 1854 and there is great excitement in Russia. The talk is only of war [the Crimean War].

Little Sasha lives in the heart of Russia, in Tamboff Province. He is seven and the oldest child of the Lodyguine family, in other words — the autocrat of the nursery.

Nania is the old, peasant nurse wholly in charge of the children. The pretty, young barynia (lady) is too busy managing her many serfs, ministering to the sick of the Lodyguines' peasant village, and entertaining endless visitors, to worry about the children. After giving birth to the youngsters she relegates them to the nursery, where they are kept until old enough to be sent to the cadet school, if they are sons, and the institute for noble girls, if they are daughters.

The nursery is a large, bare room, with the children's cribs arranged along the walls. At night Nania brings her "voilok" (a piece of felt) from a closet and spreads it out in the middle of the floor. It is her bed. A tall white, tile stove, reaching almost to the ceiling, looks like a stately monument. Little Sasha's apparent aim is to climb to the top of the stove. Whenever Nania is busy, he drags an old ladder from the closet. And the tiny, brown-curly-haired lad starts nimbly climbing. Nania, however, is sure to catch him, haul him down in disgrace, shake him and stand him in a corner. She scolds for half an hour. Little Sasha does not grieve. He has observed that Nania barks but does not bite. When she is again absorbed in her work, he makes a bee line for the ladder.

At last poor, tired Nania gets to bed. Not for long though. The clock strikes five, and she begins to adjust her felt. The little imps are at once alert.

"Nania, tell us a story!" they plead.

"If you promise to be good all day long, I shall," bargains Nania.

"Yes, yes, Nania, we promise," the children yell eagerly.

And Nania tells a hundreth time about Baba Yaga, the wicked witch, or Koshei Bezsmertny, the deathless skeleton, or Ivan Durak, foolish John, or Ptitza, the fire-bird, or the Bogotyry, the braves of the beautiful ballads.

The children get excited at every telling over the fate of each favorite. And they love Nania better than all other people. In fact she is giving them a priceless treasure — a love for all the poetical folklore of Russia.

Through this gift Sasha and his sisters and brothers became more truly, more deeply Russian, more attached to the native soil than the later generations of Russians, who were brought up on foreign languages by foreign governesses.

A little live wire like Sasha could not be kept in the nursery long at a time. His grandfathers, Ivan Lodyguine and Alexander Willieminov-Zernov, used to look at him and say, "We shall yet hear of Sasha!" He was precocious and yet not the sickly-bodied child a prodigy is likely to be. This roused the pride of the two old retired, military men. The warriors in Russia are the strong men, as they are apt to be in European countries.

Sasha throughout his life retained this double advantage of an extraordinary mentality and a highly sensitive nervous organism coupled with a vigorous, athletic body.

Both grandfathers were in their youth guard officers at the court of the Emperor Paul. They retired to barter with the native Kalmuks with vodka for vast stretches of land which they developed into great estates. On these lands they built manors for themselves, houses for their domestic serfs and villages for their peasant serfs, who tilled their thousands of acres of farm land. Tambov Province was at that remote period known as the Ukraina, meaning the borderland.1

Sasha's maternal grandfather, Alexander Willieminov-Zernov, was for years Marshal of the Nobility of Tambov Province, which meant that he held a position at least equal to that of the governor of the province. It was he and the governor who received the Tsar, or any high official who happened to visit the province. And it also meant that he and his charming wife, Pelagea, entertained very brilliantly.

Varvara, their lovely daughter, who was Sasha's mother, was trained to preside over a large estate. There was a certain jam pantry which mamma kept locked, and from which she portioned out preserves and sugar and other sweet dainties such as candied rose leaves, to her serfs. Sasha loved this spot better than any other place on earth. He would run up to mamma's room in the morning while she was still at her prayers. There she would kneel in front of a cabinet of images, devoutly crossing herself to the images, before which tiny candles were kept perpetually burning in holy oil. While she was at her prayers the serf women too would come in and ask about their orders for the day. Mamma would say a prayer, then turn to the women and give orders for dinner, then go back to her prayers, and so alternate until the chef had his orders for dinner and the women knew just what the day's program was to be, yet the prayers got said too.

From a dark corner the bead-bright, brown eyes of little Sasha were sure to peer. The burning question in his active mind was: would mamma go to the jam pantry when she finished praying? If so he would manage to bury his hand in some jam pot or other. No, they did not always go in the right direction. Sometimes mamma wanted to see, first of all, what progress the young girl serfs were making in the tapestry room, where they were weaving pretty table covers and towels with designs and fine muslines for sheets and dresses.

One day the mother was much wrought up and went straight to this room. A pretty young girl with a wealth of golden hair was in tears over her towel. Varvara Alexandrovna, as the serfs called mamma, burst into angry reproach. Yelena had misbehaved, she scolded, and must take the consequences. She would at once have her hair cut off for punishment.

Sasha understood Yelena's wickedness had something to do with the cook's son. It broke his heart to see poor Yelena sob. She was always very gentle with the children and now their good friend was in dreadful trouble. Her beautiful hair, that the children loved to stroke, was to fall by the cruel scissors! And Sasha knew having her hair cut off was the greatest disgrace that could befall a girl.

He ran back to the nursery as quickly as his little legs could carry him. At once he had his little troupe of subjects — the younger children — united in a solemn caucus. What was to be done? The beloved Yelena must be helped. And the sad, little band started out in search of mamma. At last they came upon her.

They all at once got hold of her skirts and burst into wild sobbing just as Sasha had seen Yelena do in the morning. At last, the mother succeeded in getting some sense out of them.

"Don't have poor Yelena's hair cut, please, please don't!" they pleaded.

But the mother was too horrified at Yelena's conduct to listen to what she considered the children's foolishness.

In later years, when Sasha knew more of the ways of the landlords of those days, he believed there was more than the conduct of the cook's son that offended his mother in Yelena's beauty.

______________________

A 5-kopeck coin of 1809. It is over an inch and a half in diameter and weighs two ounces. Sasha was paid one kopeck for each saint's life he read to his grandmother.______________________ "Nania, I know why the sole is flat." It was Sasha, dashing into the nursery and fairly bursting with exciting infornation.

Nania looked up from her darning, "well tell us," she ordered.

"Some pilgrims2 were here. They told Grandma the Mother of God stood on the seashore hungry one day. She took a fish from the waves and ate off a half of it, then threw the other half back into the sea. That is why the sole is only half a fish."

"The pilgrims always tell the truth," Nania said devoutly, Sasha did not wait to listen to Nania. It was a very busy day for him.

A young man was surveying land for his father. In his leisure hours this youth painted Varvara Alexandrovna' s portrait.

Now, whenever Grandma was visiting — which was the case at present — one had, as a rule, to read her from the Chetiminei (lives of the saints)3 every afternoon. True she paid a copeck for each life read, but one could not watch Dmitry Nikolaevitch paint mamma's picture at the same time.

"O, Mamma! I have earned the right to watch all afternoon," Sasha cheerfully announced, as he ran into his mother's sitting room, where she suffered herself to be painted.

Varvara Alexandrovna sat at the piano and wore a pink dress with a brown shawl gracefully draped about it. With her friend, another young woman, whom she called Evgenia Petrovna, she spoke a mixture of French and Russian.

"I went to Mlle. Veron's room and said my fable, and then I found grandma and read her the chetiminei, now I am free and can watch all the rest of the day."

The young painter flushed and bit his very red lips. The pretty young women glanced slyly at each other. "I1 est drôle," Evgenia Petrovna said to her friend in a low voice. "Kolia (Sasha's father) et moi, nous nous amusons," whispered Varvara Alexandrovna.

"Mamma!" shouted Sasha from his corner, "I didn't know men blushed. I thought only girls did."

"Will you shut up, you little chatterbox," scolded his mother, trying to cover the youth's confusion.

"I1 est agaçant ce petit bonhomme, she sighed at her friend.

"Tu est trop sévère avec lui. C' est un enfant extrêmement intelligent. Je 1'aime bien."

"Yes, but you cannot let a baby burn down the house just because he is intelligent," and Varvara Alexandrovna had lapsed into a Russian whisper. "Imagine how I found him, near midnight the other night, when I was attracted to the nursery by Nadia's coughing. Sasha was under his little bed reading Fenimore Cooperl"

"Mamma!" It was again the irrespressible Sasha. "Cleopatra is really too small for the nursery. She cries all the time. Couldn't you take her back to your rooms?"

"Nonsense, Sasha! his mother replied irritated. "Cleopatra is three and quite old enough to play. We have our share of trouble with little Kolia, but he is still in the cradle."

"Cleopatra is so foolish, Mamma," persisted Sasha. "The other day she tried to fasten a string to her little breast and then cried because she could not pull it out to look big like Nania's!"

"Veux-tu to taire! enfant terrible!" And Varvara Alexandrovna had the young genius packed off to the nursery in all haste.

______________________ At dinner that evening the village priest was one of the guests. Sasha observed him closely. Would his hand shake as usual, when he poured vodka? The father graciously offered him the decanter.

"Another glass, Otetz," he urged.

"Just one more drop exactly, Nikolai Ivanovitch, just a single drop." It was the conversation that occurred each time. He took the decanter and the usual catastrophe happened. Otetz' hand shook and his glass filled itself to overflowing.

An hour later it was tea time. the linen had been changed and the shining, brass samovar, the jams, candies etc. had been served. Varvara Alexandrovna presided at the samovar. A linen towel with Russian scenes embroidered at the ends in cross stitch, hung over her shoulder. She was washing some cups in her brass rinsing bowl and drying them on the pretty towel.

The first cups of tea were poured and served. Everyone began to drink. Then everybody put his cup down and looked at everybody else.

"Holy oil!" someone shouted.

The grandmother blushed and fidgeted. "I did not think it would be noticed," she began in a high, quivering voice. "I wanted to bring God's blessing down on our tea drinking. It really was only a drop."

The company respected the grandmother's gray hair and controlled their tempers. The samovar was, however, promptly sent to the kitchen for renewal.

______________________ Something important is going to happen, little Sasha knows and he assures the other children of it. Everybody is busy packing up. And Sasha is always in somebody's way — a shadow sure to be cast by some coming event.

At last Sasha has scented the truth. They are getting the coaches and horses out. He is positive the family is going to make a long trip. Quite consistently that very evening the children were all bathed and clean clothes were laid out for each one of them. All sorts of household articles and food, endless supplies were packed into the coaches.

Next morning, Sasha was finally informed, the family caravan would be ready to start. A large retinue of servants went along, so the barynia would not have to exert herself preparing food and looking after the youngsters.

The caravan went about visiting the neighborhood landlords for days. Entertaining such large family groups was part of a Russian country gentleman's life, in those days when railroads were yet to come. In their turn the rovers expected other caravans to visit them.

In passing by a manor, known to the children as Uncle Constantine's, Sasha's mamma turned her head quite away quickly. Sasha took this motion for a kind of religious ceremony, and also turned away his tiny brown head, but when his mother spoke he was not sure what was meant.

"To think my Kola goes to see that creature!" and Varvara Alexandrovna wept bitterly. The father had gone to shoot some birds for dinner, and Mlle. Veron sat beside the mother in the carriage. The old French governess' black eyes flashed, as she drew herself up proudly and said, "Du dédain, Varia, et surtout pas de pleurs! Du reste, cette femme aime peut-être son homme et Kola visite alors tout simplement son cousin."

Sasha heard French continually, and he understood there was something else other than a religious ceremony, and he decided not to turn his head away when they were passing Uncle Constantine's.

Another great occasion for Sasha was when his grandmother, Pelagea Ivanovna, took him to see Aunt Antonia, her daughter, the abess of a convent in their province. On one memorable visit (he was then seven), Sasha was obliged to sleep in the coach, with the coachman. By the laws of the convent, "men" were not permitted on the premises at night.

On the family's returning home, it was Varvara Alexandrovna's turn to make preparations for the great fall hunt, to which Nikolai Ivanovitch, her husband, always invited as many as three hundred landlords. The food that had to be on hand to feed the three hundred guests, their servants, horses and dogs, was something appalling. So thought Varvara Alexandrovna, and she bustled about busily, giving orders from morning to night.

So many calves and sheep would have to be slaughtered, so many geese, turkeys, chickens, ducks would have to be fattened, so many preserves cooked, so much linen woven for sheets.

Little Sasha was everywhere — especially where he was not wanted.

Only too soon the landlords arrived. Heaps of straw were thrown on the floors of several rows of rooms. On these the men slept. Beds could not possibly be provided for so many.

Sasha's father raised a fine breed of horses on his estate. And consequently stable room was not lacking for the visitors' horses.

The family zala (living room) was next to the nursery. Little Sasha liked to stand in the doorway and listen to what the landlords were saying. The war, to which some of them would go, was forever the thrilling topic. Then how the voting should turn out at the landlords' next district meeting, was something that could not possibly be left to chance. Sasha had heard his father say one had to own two hundred serfs to have the right to one vote in the district meeting. One landlord boasted that he was the father of his two hundred serfs. Whatever that meant, thought little Sasha. Another landlord replied scornfully that he was the father of his entire village!

Sasha had to become many years older before he could puzzle out the queer things these funny, old men said. In any case grown-ups are so odd, he concluded, and do not feel like little people.

Who, for instance, that had any sense, would ever have suspected good Nania of anything wicked! And yet that is what Sasha's father did when one of his fine horses was missing.

The police were sent for and the serfs were given an all-around flogging, in the hope that someone would confess. The father suspected Nania's grown son particularly. Old Nania was also made to go to the stable (the slaves were always taken to the stable to be flogged; "Na konushniu!" ("to the stable!") was the terrible cry every serf understood only too well) and flogged.

Later in the day poor, old Nania came back to the children, weeping. She raised her calico dress and showed them where her legs and been lashed. The children cried with her, which was sweet to old Nania.

Of a sudden, Sasha stopped crying. His little hands tightened into fists and his brown eyes flashed.

"When I am big," he declared, "I will do like Uncle Yevgrav. I will free my serfs and go to live in an izba [a one-room hut]. Some old man and woman will want to wait on me, just out of love."

"We too" repeated all the other little ones, "will do like Uncle Yevgrav," and they made little fists.

"O Sasha," remembered little Julia, the next in size. "You do not know what happened at the table while you were at Grandma's. Papa found a beetle in his soup. He was very angry and ordered Vasili to call the cook. When the cook came he made Vasili put the plate of hot soup on the cook's head!"

"I must go and console the cook," and Sasha ran to the kitchen.

And yet the Lodyguines were known as good landlords. They were horrified to hear of some of their neigbors' cruelties. One landlady of the vicinity was enraged at finding a corsage ironed carelessly. She had the young girl that had ironed it laid on the ironing board and a red hot iron passed over her bare breast.

There were circumstances when Nicholas Lodyguine had a serf flogged with the approval of his Russian contemporaries.

He was having land surveyed and divided amongst the peasants. One peasant came with a bribe, a sheep, hoping the landlord would give him the best land. When N. Lodyguine understood what was wanted, he ordered the sheep taken from the peasant and had him flogged in the stable. Then he gave him back his sheep and said "That is what it costs to bribe a Lodyguine." Any one who knows that bribing is and has been the curse of Russia will understand that though brutal and crude, the gesture was not lacking in a certain grandeur.

Fortunately for Sasha and the other children, one always had the mill to run to and there so much fun awaited one that all sorrows were forgotten. The mill stood on a little river. And playing in and around the water on a fine day — could anything bring greater glee to children's souls? It was bliss.

Even in those early days what became the obsession of his life — aviation — began, in a simple way, to haunt little Sasha. He saw the birds fly. If he made himself a pair of cardboard wings and fastened them on himself, could he fly? was the question that recurred to him continually. He took sister Julia, the child next to him, into his confidence. She was enthusiastic: what big brother thought was always right.

Sasha went to much trouble to make the wings. When they were ready, the children were sure they would work. Sasha could fasten them better on his sister than on himself. She was perfectly agreed. They climbed on top of a shed. When the wings were fastened on Julia, Sasha was to give her a push and she would fly. He did give the push but Julia fell to the ground and hurt her ankle, instead of flying.

The father heard her cry. He ran out, and when he learned what was the matter, he gave Sasha so sound a thrashing that all thought of flying was forgotten for the time being.

Sasha's cup of joy, however, overflowed again when some Turkish prisoners were brought to the Lodyguine village from the front.

The little boy was already intensely living the War. Every morning his father read his mother the news in the zala. And little Sasha would sit in a corner and drink in what he could catch. Especially the wonderful feats of a certain Cossack, Koshka, were very exciting to him.

When the Turkish prisoners were brought, little Sasha fairly stood on his head. His father took out the gun of one of the prisoners and had two guns made for Sasha. It was treating him like a big man.

Sasha's first hunt took place when the snow was on the ground. He told his father's hunter, a serf, all about his plans.

He would stay awake all night under a tree near the house, where the rabbits were apt to come.

The hunter suggested Sasha might fall asleep.

Sleep! He! Sasha was offended.

In the evening it was so cold and lonely, under the tree, but Sasha was too brave to give in. After a long time, however, he was overcome by sleep.

The next morning, when he awoke, he spied many little foot prints on the snow, quite close around him. The rabbits had made fun of him! And nearby stood the hunter. He too was laughing at him.

When Sasha was ten, his childhood days were considered over. He was sent to a cadet school, at Varonesh. And for more than ten years he always dangled a sword at his side. His father expected him to be a military officer, as all his ancestors had been for generations.

IN THE SECOND CHAPTER OF ALMA'S BIOGRAPHY OF HER HUSBAND, HE DISTINGUISHES HIMSELF AT CADET SCHOOL IN SCIENCE AND MATHEMATICS, AND ORGANIZES HIS FELLOW STUDENTS TO PROTECT YOUNGER BOYS AGAINST BULLYING. FROM READING IN THE SCHOOL LIBRARY, HE BECOMES INTERESTED IN AVIATION. Chapter 2

THE CADET

Sasha has been at the Varonesh Cadet School several years.

He is known as a boy who does not make a quarrel, but never fails to accept one that is thrust upon him. Himself he is endowed with a sturdy little physique. His tender heart, however, causes him to champion the weaker boys against the bullies.

Together Sasha and a group of friends have formed a society for the protection of small boys. Amongst these is Sasha's cousin, Sergei Krivenko (a future literary man). The latest convert to the principles of the reformers is a young Cossack. He is one of those heretofore feared by the smaller boys.

It is a holiday and the boys are at play. A small boy annoys the Cossack. The latter raises his hand. He is red with anger. Then suddenly he remembers. He has promised to protect the small boys. His face turns deathly pale. He drops his hand and walks away. And Sasha and his friend adore him from that day on.

Sasha soon distinguishes himself in chemistry and physics and mathematics. The professor of chemistry and physics makes him his laboratory assistant, but in the languages he is so poor a scholar that his teachers send him to study his lessons in the school prison (kartzer).

Over the boys' heads hung always the threat of cruel floggings. Despite it, or rather because of it, playing tricks on the teaching officers was rather a temptation to the more daring cadets. The risk of being caught — that was the great thrill.

Only a few years before, the death of Nicholas I had occurred. The reforms that brightened the early years of Alexander II's reign had not yet been applied throughout the vast Empire. And much of the harsh discipline of Nicholas I still obtained.

Flogging in the cadet schools was an instance of this iron discipline,

When a boy was sentenced to be flogged, his back was bared, he was strapped to a bench and two strong soldiers stood on either side the bench with whips. And each in turn came down on the helpless young back with his cutting lash. A doctor stood by and from time to time felt the victim's pulse, for the boy was not actually to be killed!

Sasha is noticed by his masters as a boy who can write verses. On one occasion, when a Grand Duke comes to visit the school, the commanding officer leads him about in the classes. Noticing Sasha in one room, he remarks to the Grand Duke, "Here is a boy who can write poetry." Politely the Grand Duke answers, "He must write me some verses," and then passes on. Probably the Grand Duke never meant that the incident should have consequences. The commanding officer, however, takes the matter seriously. When the visitor has passed out of sight, he turns to Lodyguine and another boy whose handwriting is good. "Lock yourselves in that room and do not dare to reappear until Lodyguine has written some verses and I____ has copied them! "The Grand Duke wants verses."

Sasha is not at all poetically inspired. At last after racking his brains for what seems an eternity, with no other muse but hunger, he actually produces several verses, which are eagerly copied by the ravenous young penman.

When the commanding officer ceremoniously handed the verses to the Grand Duke with, "The verses you ordered, your Highness," his Highness looked blank for a moment. He did not remember he had ordered verses!

Another distinguished visitor was Alexander Humboldt. When shown the curriculum of the school, he said, "I wish I knew all that!" The remark was appreciated, especially by the boys.

The hideous wrong of the brutal flogging ever rankled in the soul of every boy in the school. Many it made madly reckless.

A tragedy brought the matter to a crisis.

A certain cadet, who has received many floggings, becomes defiant. He runs from the soldiers, that pursue him up several flights of stairs and through many halls. At last he appears on a small balcony, near the top of the house. The soldiers see and reach him. Before they can grasp him, he leaps into the air. The other cadets, who have followed the boy breathlessly, see the desperate leap. They rush below. The boy lies on the ground dead.

Flogging was at once abolished.

In the school library there were naval reviews which took up the question of aviation. Sasha spent all his spare time poring eagerly over these messages from the enchanted world of flying. Thus was laid the foundation of what became the absorbing passion of his life — the study of the principles of aviation. Often he was seen lying on the ground, trying to puzzle out how birds fly. A small meteorological station, connected with the school, also gave young Lodyguine an opportunity for various kinds of scientific research. His masters, noticing his interest in the station, eventually put him in charge of it.

THE THIRD CHAPTER OF ALMA'S NARRATIVE TELLS HOW LODYGUINE, WHOSE FATHER REFUSED TO SUPPORT HIM WHEN HE DECIDED ON A CAREER IN SCIENCE INSTEAD OF THE MILITARY, LEARNS LOCKSMITHING TO PUT HIMSELF THROUGH UNIVERSITY. FUNDED BY CONTRIBUTIONS FROM HIS FELLOW-STUDENTS, HE MAKES HIS WAY ACROSS EUROPE WITH PLANS FOR HIS AIRPLANE IN A QUIXOTIC ATTEMPT TO HELP THE FRENCH REPUBLIC, WHICH IS FIGHTING THE FRANCO-PRUSSIAN WAR. Chapter 3

Mme. Sieroff, the wife of the Russian composer, and the mother of the Russian painter of the same name, published a biography of the composer after his death, some years ago. In it she speaks of a class in locksmithing young Lodyguine4 taught at her house.

This was in 1869.

After the emancipation of the serfs in 1861, there was a time of great awakening in Russia. The young people of good families went amongst the newly freed peasants to teach them along various lines. "Enlightening the younger brother" was their cry. These boys and girls themselves felt great need of manual training. They had been accustomed to be waited upon by serfs, and were unable to do any kind of physical work.

The class at Mme. Sieroff's was made up mostly of boys and girls feeling this deficiency. There were, however, also some older persons, notably a well-kmown princess. Mme. Sieroff knew that A.N. made his living outside of the time he spent at the university, working at locksmithing. So he was one who could teach her young friends something about metal work.

This was a period of much bitter strife between the parents and the younger generation. Through Peter The Great's "window to Europe" — St. Petersburg, freedom of thought was blowing in from western Europe in a steady stream. The older people were for keeping the time-worn forms of life and the younger generation were for the new. In consequence there was much intense feeling on both sides.

A.N.'s father refused to provide for him, when he insisted on becoming a scientific instead of a military man. In Tula, at the iron works, he learned locksmithing, to have some immediate means of support, while a student at the university.

And yet to please his father A.N. had gone to Moscow to attend the Military Academy of that place for two years, when he had finished his course at the Cadet School.

A very interesting experience of this period was that he often heard Rubenstein5 play at the house of a musical aunt, whose husband was a Moscow judge.

It was also while at the Moscow Military Academy that A.N. was almost persuaded to become a writer. At least the other cadets declared he was going to be one.

The professor of Russian literature was a known writer and a regular contributor to a certain review.

When correcting the cadets' papers one day, he came upon the description of a scene occurring at a very poor boarding house in St. Petersburg. It was A.N's. The professor said it was a very lifelike setting-forth of conditions, and that he would have it published in his review. The story was published, but A.N. was too deeply interested in his flying machine dream to be tempted.

When the two years were up A.N. had promised to spend at the Moscow Military Academy, he further tried to please his father by joining the arnmy. His was the 8lst Bielefsky Infantry Regiment. A.N. was so skilful a marksman that he was put in command of a company of sharpshooters. He was also found to be an expert fencer and had to instruct the soldiers in fencing.

The lure of science, however, was too strong for A.N. He obtained his discharge from the army in 1868, while his regiment was stationed at Tula. It was in this way that A.N. had happened to be at Tula, and that he now could be useful to the group of young enthusiasts who were meeting at Mme. Sieroff's home to learn 1ocksmithing.

Mendeleeff was at that period a professor of the University of St. Petersburg. One of A. N.'s proudest memories was that he was a pupil of the inventor of the "Table of Elements."

At this time also, Kuropatkin was a cadet at the Military Academy of St Petersburg. A.N. used to go to see Kuropatkin at the Academy, for the two young men were friends. Very often, Russian friends do not agree. A.N. and Kuropatkin were very Russian in this respect. Many were the lively discussions that took place between the two promising youths.

In referring to the difficulty Russians find to be of one mind on any subject, A.N. used to say, "Where there are two Russians, there are sure to be three opinions."

In the early 70's, when Gen. Skobeleff made conquests for Russia in central Asia, Kuropatkin distinguished himself as the General's clever young aide. A.N. was bitterly dissapointed in his old friend when he did not live up to his earlier reputation in the Russo-Japanese War.

A.N. shared his poor quarters with another student, a connection, one of the Krivenko boys. Krivenko was a student at the Military Medical Academy of St. Petersburg. A peasant girl cooked for the two students.

A.N. spent every available hour drawing the plans for his great scheme — an airship heavier than air.

Nowadays we can hardly imagine a time when the airship heavier than air did not exist, and when the world believed only in machines lighter than air. A. N. did not worry about the world's opinion, and forged boldly on.

Krivenko has boasted of his extraordinary pal at the Medical School. One day he comes home wildly excited. His agitation concerns A.N. and the Franco-Prussian War, that is going all wrong for the poor, young French Republic. Something must be done to save France! So it was decided by her young sympathizers of the Military Medical Academy of St. Petersburg, assembled in a meeting called in haste to consider that very matter. But how was the problem to be approached?

Someone had a brilliant notion.

Who better could represent them than young Lodyguine, who had his plans for an airship ready, and what of all things could be more useful in warfare than an airship?

A.N. must at once go to France with his plans and propose them to the Committee of National Defense.

Krivenko reminds the young enthusiasts of the distressing fact that both A.N. and he are as poor as church mice.

The boys are not going to let so mean a consideration stand in the way of the great project. A hat is at once passed about. And the sum of 98 rubles (about $50), mostly in grivennicks (10 kopeck pieces) is realized.

Someone remembers the name of a well-known Polish general who has gone to France, and is making common cause with the French. A.N. is to apply to him for the necessary introductions in France.

Krivenko runs home with his hat full of money.

When he tells A.N. the glorious project and shows him the money, A.N. takes the whole matter very seriously. With the assurance and impetuosity of sturdy youth, he is ready to start the next day.

The peasant maid draws her own conclusions. She is perfectly aware of the extreme poverty of the friends. How can they honestly have come into posession of a whole hat full of money? she wonders. She decides they have undoubtedly murdered and robbed somebody, and she spreads this supposition about the neighborhood as a fact.

A.N., like many young noblemen of the time, affects the red peasant shirt, out at the belt, and the high boots with the trousers tucked in them.

This is to represent his rapprochement to the "younger brother" and shows the liberal trend of his political mind.

The youthful hero thrusts his precious plans, his hat of money, and some extra clothing into his valise, and starts out for the scene of The War.

At Paris he finds that the Committee of National Defense has removed to Lyons. Besides the Polish general, Monsieur Nadar, the well-known Parisian photographer, helps him. Monsieur Nadar is known to be interested in aviation. A. N. is for that reason sent to him with his plans. The youthful inventor speaks poor French, but he explains his plans to Nadar and tells him his aim in coming to France. He succeeds in impressing Nadar, who sends him to Lyons to see the Committee.

The Committee actually has a technical body examine the plans, and they are declared worth trying. A credit of 50,000 francs is voted for the construction of the machine and it is decided to have it built at the Creusot Works.

Then there ensues a lengthy correspondence between the Committee and the Works, regarding the details of construction. Meanwhile A.N. becomes fascinated be Giuseppe Garibaldi, who is operating at Dijon, and is also a foreigner come to aid France.

All through his life, A.N. remained an ardent worshiper of this indefatigable fighter for liberty.

When at length the young Russian is sent from Lyons to Creusot, his fellow travelers regard him with suspicion, Fearing his precious plans might be stolen, A. N. watches his valise anxiously. Added to this circumstance, he looks outlandish to the French. They take his red shirt for a mere disguise and decide he is a Prussian spy.

He is arrested as such, and taken from the train, despite his vehement insistence that he is a Russian inventor.

A crowd gathers and quickly becomes enraged. Cries of "a la lanterne!" grow menacing. The police has to protect A. N. Some one says there is a workingman in the next village who speaks Russian. Even in great excitement, the French are kind. The authorities decide to send for the Russian expert before making up their minds to shoot the prisoner. After some delay the workingman arrives as proud as a peacock. He has suddenly become important. On him depends the fate of a man! He advances and asks A.N. some questions in a very broken Polish. A.N. is very careful not to betray the fellow. He answers in Russian, with an air of as much appreciation as he can assume. This bit of tact wins the workingman, who turns to the gaping crowd to assure them that the prisoner is a sure enough Russian.

A.N. is saved and no one is the wiser as to the linguistic achievements of his savior.

There is now a comical revulsion of feeling in the crowd. They become as madly joyous as they were hostile before. Mothers raise their babes to show them the noble, young hero who has come to help France. At Creusot much time is spent in discussing the best methods of construction.

Meanwhile events are moving fast at Paris. The Committee of National Defense informs A.N. they need money more than an airship. The young Russian returns to Lyons to travel to Paris from there. In Lyons he witnesses the grandest sight he has ever seen: the proclamation of the French Republic. The whole city is in the streets, crowding around a well-known actress arrayed in white and standing on a raised platform. The actress leads the mighty throng in singing the Marseillaise.

A.N. reaches Parls just in time to catch the last train before the Commune. There is nothing for him to do but return to St. Petersburg.6

[THIS PART WAS NEVER WRITTEN. IT WOULD HAVE COVERED LODYGUINE'S EARLY CAREER AS AN INVENTOR (WITH A HIATUS ON A FARM ON THE BLACK SEA), HIS INVENTION OF THE LIGHT BULB, HIS FIRST STAY IN THE UNITED STATES, HIS WORK WITH WESTINGHOUSE AND OTHER COMPANIES, HIS MARRIAGE TO ALMA SCHMID, THE EXHIBITION OF HIS LIGHT BULB AT THE PARIS EXPOSITION OF 1900, HIS ROLE IN ELECTRIFYING THE NEW YORK SUBWAY, AND HIS DECISION TO RETURN TO RUSSIA DURING WORLD WAR I.] PART II

SOME CHAPTER TOPICS WERE TO BE:

- Caucusus and farm on Black Sea.

- France & the States.

- The wife of Alexander Lodyguine.

- Return to Russia. Why? Alexander Lodyguine because [he was] a nationalist.

______________________

Emma Virginia Schmid ("Jeannie," later Virginia Schmid Cooper, California artist, my grandmother), the Schmid sister Alexander Lodyguine almost married (but didn't).______________________

HERE WE PICK UP THE NARRATIVE FROM THE MEMOIRS OF ALMA DE LODYGUINE'S NEPHEW, DR. CHARLES WILLIAM COOPER (MY UNCLE CHARLIE, SON OF ALMA'S SISTER EMMA VIRGINIA, KNOWN AS "JEANNIE"). THESE MEMOIRS WERE WRITTEN IN 1977-80, WHEN DR. COOPER WAS RETIRED AS PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH AT WHITTIER COLLEGE IN CALIFORNIA. OUT OF THREE VOLUMES OF MEMOIRS, THE FOLLOWING EXCERPTS DESCRIBE THE FAMILY'S REMEMBRANCES OF "UNCLE ALEXANDER" LODYGUINE. SOME OF THE MATERIAL CONCERNING LODYGUINE'S EARLY LIFE DUPLICATES ALMA'S NARRATIVE.

THE FIRST EXCERPTS ARE FROM THE FIRST VOLUME OF DR. COOPER'S MEMOIRS, FAMILY ROOTAGE, SANTA BARBARA, CALIFORNIA, 1977.

Pp.81-84:

OUR NARRATIVE BEGINS WITH ALMA'S FATHER, FRANCIS XAVIER SCHMID (MY GREAT-GRANDFATHER, KNOWN AS "GROSSPAPA") A SCHOOLMASTER WHO HAD IMMIGRATED FROM BAVARIA SOME YEARS BEFORE. HE ESTABLISHES A SCHOOL IN PITTSBURGH AND TAKES IN BOARDERS, INCLUDING ALEXANDER LODYGUINE, WHO IS IN PITTSBURGH WORKING FOR WESTINGHOUSE. LODYGUINE PERHAPS HAS A FLIRTATION WITH VIRGINIA ("JEANNIE"), THE YOUNGEST OF THE FOUR SCHMID SISTERS (HELEN, ALMA, MARGARET ("MARGO"), VIRGINIA). LODYGUINE RETURNS TO PARIS.

During the first year of this school (1893-94), Francis Schmid engaged in a business partnership with Miss N. G. Barclay, who had taught his daughters in the Washington Seminary. She had written Mr. Schmid that she wanted to come to Pittsburgh to open a private school, and it was he who proposed that she join him in what he was already undertaking. She might also rent a room and board with the Schmid family. They came to an agreement.

With still more rooms than were needed for family and school and Miss Barclay, Mrs. Schmid (for Dena [Christina Schmid, my great-grandmother] was surely the managing head) was able to rent out two further rooms: one to M. Charles Fayès, volatile Frenchman; the other to M. Alexandre de Lodyguine, quiet Russian of middle age, an electrical engineer. They too were to be boarders.

It was therefore a large household presided over by my grandmother and her graying husband. At home were two marriageable daughters — for Alma, after two years teaching out in Denver, was to be off in Kalamazoo, and Helen, the eldest, had been married two years.

Then there were also the two mature and fascinating foreign gentlemen — and the spinster co-principal.

Monsieur Fayès, who taught French privately, was recently widowed. His Latvian wife had been a friend of Dena Schmid. He was an assertive but kind-hearted man, something of a braggart with imagined African exploits and other conversable adventures. During the evenings when Jeannie wasn't at art school, M. Fayès taught her to play chess. Whether he courted her or not — as he may well have done, for she was an attractive eighteen — he gave her a silver ring, a wide band with three fleur de lis, French royalist memento. (The ring, given to me in time by my mother, became my engagement ring to Edris — awaiting the time I could afford a diamond further to plight our troth.)

Or was it M. de Lodyguine who gave Jeannie the ring, as my sister Christine insists? [Christine Cooper, later to become Christine Cooper Angier, my mother.]

Lodyguine was in his mid-forties, a sturdy Slav in stature, whom my grandfather described as having "made himself a name and fame in the scientific world as the inventor of the first incandescent lamps." He was then "in the service of the Westinghouse company in Pittsburgh and Allegheny. . . an unassuming, sober and thoughtful gentleman. " He was not married.

Westinghouse had won over Edison in securing the contract to light the Chicago world's fair (Columbian Exposition) of 1893. The Westinghouse lamp had been inferior to Edison's, so George Westinghouse brought over Lodyguine from Paris to further his program of research and development, Lodyguine's work already recognized in Europe.

In the spring (1894), M. de Lodyguine left Pittsburgh and returned to Paris. He intended to close up his apartment there (according to a tradition in our family), then to come back to Allegheny [now part of the city of Pittsburgh], lay siege to the heart of Jeannie and marry her! — though I am here to assure you that that was not how it worked out. Rumor had it (was this the teasing M. Fayès?) that M. de Lodyguine had more in Paris than mere furniture to dispose of, and that his French mistress clawed out the eyes in the photograph of his American sweetheart!

There were tensions in the Schmid household caused by the presence of Miss Barclay, who, as it happened, was "either reticent and sulky or fault-finding, quarrelsome and insulting;." She would deliver "long tirades against foreigners — which may have been no more than evidence of their attraction for her! She would also "disclaim the friendship of my wife" (my grandfather vividly remembered) and quite irrationally "justify retaliation and approve the burning of Negroes!"

There in the Schmid household Miss Barclay and M. Fayès had been "constantly on the war-path, while M. de Lodyguine, who was always courteous, [had] found favor in her eyes, and she was said to have become hysteric[al] in school on the day when he left." M. de Lodyguine did not return to Pittsburgh as expected.

Miss Barclay conspired unsuccessfully to take the school away from Professor Schmid by telling the pupils that it would be moved the next year to a new address (which she gave them). When she left the Schmids at the end of the year, only four girls followed her in her new venture, which failed. And Professor Schmid's College Preparatory School for Girls and Young Ladies reopened in the fall blessedly without her...

______________________

______________________

IN THE NEXT EXCERPT, ALMA, WHO HAD BEEN AWAY WHEN LODYGUINE WAS IN PITTSBURGH, IS IN PARIS. LODYGUINE IS ALSO IN PARIS, AND ALMA BECOMES ACQUAINTED WITH HIM. THEY FALL IN LOVE AND ARE MARRIED. ALMA APOLOGIZES TO JEANNIE.Pp.86-89:

The year 1894-95, when Jeannie Schmid was in her second and final year as student at Bishop Bowman Institute, was to be a difficult one in the Schmid household--but not unmixed with blessings. . .

. . . . .

Alma, the second Schmid daughter, having taught three years in Denver and Kalamazoo, was now aged 23 and intent upon improving her modern languages by living for a time in Europe — and Margo, aged 20, with musical talent and ambition, wanted to study piano at the Paris Conservatory. Their father paved the way for them by correspondence, arranging with M. Charles Fayès, the family friend, to meet their train in New York City and to see them to their ship.

The September crossing of the North Atlantic in their Dutch steamer was rough, and the Schmid sisters were desperately ill — for it was before the time of ship stabilizers and dramamine. In Paris their boat train was met by Dr. Fayès, physician brother of M. Charles F. He helped to find a room for the young ladies and a position for Alma as teacher of English in a private school near Montmartre, a quartier even then of artists and intellectuals. Margo applied at once for admission to the Paris Conservatory of Music — and was refused! The set rules: no applicant accepted over 16 years of age; no applicant accepted who had not been resident in France for at least one year.

What to do? Remember that it took a good month for a transatlantic exchange of letters. So it must have been late in October when Margo followed her father's advice and went on to Stuttgart (50 miles to the east of Baden-Baden and Karlsruhe), the historic capital and cultural center of the German kingdom of Württemberg. [ED. NOTE: Baden-Baden was the site of one of Franz Schmid's early teaching positions.] There Margo's talents were at once recognized and she was admitted to the Conservatory of Music as one of the few advanced pupils of Professor Pruckner. He was an exacting taskmaster and boasted himself a pupil of Franz Liszt. Margo was to practice from 7 to 8 hours a day!...

In Paris — whether through Margo (who of course knew him) or through Dr. Fayès — Alma became acquainted with the Russian engineer who the previous year had lived in the Schmid home in Allegheny while she had been off teaching in Kalamazoo. Whatever may have been his attraction to Jeannie, upon whom he may have exerted some fascination as they played chess in the Schmid parlor, Alexandre de Lodyguine had been in no way engaged to Jeannie, whether or not it had been he rather than Mr. Fayès who gave her the silver royalist ring, and despite the eyes scratched out of her photograph!

At any rate, in Paris that fall the 47-year-old scientist/engineer fell deeply and marriageably in love with Jeannie's older sister, the beautiful Alma (for all the Schmid girls were handsome), and she with him.

A month after Margo's going off to Stuttgart, Alma and Alexandre both wrote to her father of their love and asked his consent (as one then did) to marry. The letters from Paris greeted and surprised papa Schmid on his 65th birthday.

There came another letter, too, from Alma to Jeannie, asking forgiveness of her beloved younger sister, whom Alma thought to be fond of Alexandre, and explaining that love had simply overwhelmed them.

Professor Schmid as father was reluctant to give the consent asked for, but he did feel that parents "had no right to thwart the inclinations of their children unless their affection is misplaced." And Mr. Lodyguine was certainly not "objectionable by reason of physical, mental or moral disease, either hereditary or contracted" —Franz Schmid considering him to be "a sound man" —but, after all, he was in fact several years older than Alma's mother Dena and he had "no situation" (that is, settled employment as engineer) despite his "talents and high attainments."

Papa Schmid must have stalled, perhaps thinking of his own May-and-December marriage with Dena — but upon reiterated appeals from Paris, he yielded and noted in his Reminiscences that Alma and Alexandre were "legally" married on March 28th, 1895 — he meant merely that there was a civil rather than church wedding.

We cannot share with Jeannie her thoughts and feelings upon receipt of Alma's letter — had she perhaps been just a bit in love with Alexandre? But knowing her as she later was to be, we can imagine the generosity of heart with which she responded.

______________________

AS THE NARRATIVE CONTINUES, LODYGUINE'S HEREDITY FROM THE LANDED BOYARS OF IMPERIAL RUSSIA IS RECOUNTED, AND HIS JOURNEY TO PARIS, AS A STUDENT, WITH PLANS FOR HIS AIRPLANE IN AN ATTEMPT TO HELP THE FRENCH REPUBLICANS.

Pp.89-92:

As Alexandre was to become one of my uncles — and a remarkable one — something more should be said about him.

Alexandre de Lodyguine is the French form and spelling of his name, the de added to indicate that he was of the nobility. Alexándr Nicholáevich Lodýgin comes closer to the Russian (the o pronounced as continental a and the g hard). His middle name was patronymic, "son of Nicholai." He traced his descent from the 4th century Lithuanian (Slavonic) King Weidewoot of Porussia (Prussia) through intervening dukes, princes, etc. One branch of descent was to be the Lodygins, another the Romanoffs — Michael Romanov in 1613 being elected Czar of all Russia, his descendants occupying, the imperial throne until the Revolution of 1917.

Alexandr Lodygin's grandfathers were both Guards officers at the imperial court of Czar Paul in St. Petersburg (now, of course, Leningrad [ED. NOTE: and now again St. Petersburg]) Paul reigned only from 1796 to 1801. Mad with power, he was assassinated. On retiring from the court these Guards officers bargained for vast tracts of land in Tambov province southeast of Moscow on the upper border of the rich agricultural Ukraine. [ED. NOTE: For the location, and the use of the word "Ukraine" ("frontier"), see Note 1 at the end of Part I of Alma's narrative above.] Being privileged boyars or gentry, they built manor houses and villages for their serfs, and tilled thousands of acres of farm lands.

Born in 1847, Alexandr was already aged 14 when, under liberal pressure, Czar Alexandr II more or less emancipated the serfs and undertook to provide them with land. With removal of the cheap labor of serfdom, the economic position of the boyars deteriorated. The Lodygin family must gradually have lost both wealth and lands — much as this transformation is depicted in Chekhov' s powerful drama The Cherry Orchard.

Called Sasha in the family, Alexandr was a bright, sensitive, strong boy. At an early age dreaming of flying, he constructed cardboard wings, fitted them to his sister Julia, and pushed her off the barn roof — she suffering a sprained ankle and he tanned britches. At age 12 he was sent off to Junior cadet school, then to Military Cadet School at Voronezh, a hundred miles away. There he was a good student in chemistry-physics, assisted the teacher, and was pointed out to the visiting Grand Duke.

Sasha read with passionate interest everything he could find on aviation theory. To satisfy his father, he went to Military Officers School in Moscow and served as Commander Lieutenant of Sharpshooters in the regular Army for three years (1865-68). Thereafter he took a job briefly in an iron works and became a skilled locksmith — some youth from the outmoded gentry were then learning useful trades.

In St. Petersburg, where he became a student in the Technological Institute, Alexandr lived in poor student quarters. He and a kinsman, who was studying medicine, shared rooms and a peasant girl to cook for them. He hobnobbed with Kuropatkin (later on, a distinguished if finally defeated general), and spent all his free time working on plans for a heavier-than-air flying machine — this was 30 years before the Wright brothers began their study.

The year 1870-71 saw the Franco-Prussian war in western Europe. Events moved swiftly: the defeat and capture of Napoleon III in September, collapse of his Second Empire, revolutionary struggle in France, birth of the Third Republic... Fighting continued into the spring for control of France.

In far-off Russia, Lodygin and other students were ardent supporters of the Republicans in France as opposed to the Revolutionaries. A group of Lodygin's friends pitched in, collected money, and sent him to Paris with his aircraft plans to help the Republican cause.

In red peasant shirt and pants tucked into high boots (to show his republican sympathies), Alexandr set off, carrying his valise with the money, change of clothes, precious plans, and name of a Polish general fighting with the French and known to be interested in development of military aviation. The Committee on National Defense having fled Paris for Lyon, Alexandr followed it there. His plans for an airplane were carefully studied, an appropriation of 50,000 francs authorized for building it in the machine works at Creusot, where Lodygin was sent. On the way he was almost lynched on a handy lamppost, for in his strange attire, clutching his valise suspiciously, mouthing but a foreign French, he was thought to be a German spy. Only his voluble speaking of Russian to a Polish workman convinced the crowd that he had, rather, come to help the Republican cause in France.

In Creusot he waited for the promised funds — they did not come — the hard-pressed Committee on national Defense canceled its financial support. Lodygin's experimental plane was never to be built. (But another Russian inventor did succeed in flying his own plane several years before the historic flight of the Kitty Hawk in 1903.) Back in Paris again briefly, Alexandr caught the last train out of the city before the Revolutionary Commune took over, barricades once more in the streets, burning of the Tuileries Palace.

______________________

Pp. 92-94:

BACK IN RUSSIA, LODYGUINE PERFECTS HIS LIGHT BULB AND VARIOUS INVENTIONS IN METALLURGY. AFTER A STINT ON THE BLACK SEA, FIRST HELPING TO FOUND A MODEL FARM THEN BECOMING A PILOT ON A BOAT, HE RETURNS TO ST. PETERSBURG, WHERE HE BECOMES INTERNATIONALLY FAMOUS AND MEETS WESTINGHOUSE, WHO INVITES HIM TO PITTSBURGH. ON A RETURN TRIP TO PARIS, HE MEETS AND MARRIES ALMA, WHO HAD BEEN AWAY.

But all was not lost for Alexandr Lodygin. He now turned to perfecting the electric lamp that he had invented to light his planned aeroplane.

The Grand Duke Constantine, as Grand Admiral, gave him space in the magnificent Admiralty building for his experimental work developing the incandescent lamp with carbon filament. He had already demonstrated this in 1870, secured patents for it in Russia in l871, in France in 1872, in U.S.A. 1873, and he was awarded the Lomonosov Prize of 1,000 rubles by the Academy of Science in 1874. Indeed in that year a small company of speculators undertook to manufacture the lamp, but their efforts were premature and their scheme failed when Lodygin himself withdrew — he did not yet have equipment adequate for creating the necessary vacuum satisfactorily for his lamps, though other Russian physicists were working on this, and the improved lamp was demonstrated in Paris in 1875. (it was not until 1878 that Edison's incandescent lamp was reported in the American press, and Edison never seems to have denied priority of the pioneering Lodygin lamp.) [ED. NOTE: See Rita de Lodyguine Faust's "Who Invented the Electric Light Bulb - Edison or Lodyguine?" below.]

Alexandr Lodygin worked briefly as an engineer at the Artillery Arsenal in St. Petersburg. A number of his inventions were in metallurgy: for extracting various metals from their ores, for cutting and welding and riveting, for hardening armor plate. He designed a flying torpedo — and in the Department of Standards apparently calibrated instruments. But at some point in doing all this he suffered a nervous collapse despite his bodily strength.

To recover his health he went off with friends to establish a model farm on the eastern shore of the Black Sea — a settlement that in time became the present city of Tuapse. He hiked and hunted in the rugged Caucasus mountains, sailed and fished in the sea — was licensed to pilot and command a lateen-rigged felucca used for rescue missions along the coast. He designed a diving suit and sent the drawings up to St. Petersburg. This reminded the Government of his whereabouts and the idealist settlers were recalled to safety, for it was the time of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78.

Once more in St. Petersburg, Lodygin worked as engineer-metalurgist in the making of shells for coastal artillery, then as engineer and chemist for the company manufacturing arc lamps.

The inventor-engineer now moved in the cultural circles of St. Petersburg society — Uspensky introducing him to Turgenev the novelist. In 1883 he was sent off as Russian delegate to the Electrical Exposition at Vienna, and there was presented to Emperor Franz Josef. On behalf of his government, Lodygin gave a banquet for the international group of scientists, Crown Prince Rudolph and Princess Stephanie being the imperial guests. On Lodygin's return to St. Petersburg he was awarded the Order of St. Stanislas, certainly by Czar Alexandr III himself, and at some point Lodygin was named a Counsellor of State.

Lodygin's scientific work continued. Invention of incandescent lamps using tungsten, molybdenum, osmium, iridium and rhodium were patented in 1890 — these patents sold to General Electric in 1906. Now living much of the time in Paris, Alexandre de Lodyguine had become an international figure, and his work was prominent in International Expositions, such as that in Paris in 1889.

It was in Paris that George Westinghouse met him and invited him to come to America as a consultant on electric lighting — and this brought him to Pittsburgh and into the Schmid family. [ED. NOTE: This refers to his first trip to America, when he met "Jeannie" Schmid, but not Alma, who was away teaching in Kalamazoo. It was in Paris again that he finally met Alma.]

The marriage of Alexandre de Lodyguine and Alma Schmid took place in Paris March 28, 1895. And — all in good time — he was to be my "Oncle" Alexandre...

______________________

IN 1895, MARGO SCHMID, STUDYING PIANO IN STUTTGART, SUFFERS A COMPLETE BREAKDOWN, AND MRS. SCHMID SAILS TO EUROPE TO BRING HER HOME TO THE U.S. WHILE IN PARIS, THEY STAY WITH ALMA AND ALEXANDER, AND FIND THAT ALEXANDER IS OUT OF A JOB.P. 96:

Upon exchange of letters with Margo's parents in Allegheny, it was decided that Alma should go to Frankfurt and return with her sister to Paris — and then mother Dena would go over to Paris to bring Margo home again to America.

This my grandmother did in October 1895. The Atlantic was calm for her crossing. Upon her arrival by boat train at the Gare du Nord in Paris, Alma and Alexandre somehow failed to find her, so Dena crossed Paris alone in a cabriolet to the Lodyguine address in the Latin Quarter — Margo waiting for her there. The Lodyguines were living "in narrow circumstances." Possibly without immediate engineering work and income at the time, Alexandre may have been busy organizing his own company that in 1896-98 was to manufacture his electric lamp.

______________________

BY 1900, JEANNIE (HAVING GOTTEN OVER ALEXANDER!) IS MARRIED TO CLARENCE LINCOLN COOPER ("LIN," MY GRANDFATHER), WITH WHOM SHE IS LIVING IN AN APARTMENT IN PITTSBURGH WITH THEIR FIRST CHILD, MADELEINE VIRGINIA (THEY WOULD EVENTUALLY HAVE FOUR MORE CHILDREN, INCLUDING MY UNCLE CHARLIE, WHOSE MEMOIRS WE ARE QUOTING, AND MY MOTHER, FRANCES CHRISTINE.) THE LODYGUINES' FIRST CHILD, MARGARITA ALEXANDREVNA (MY MOTHER'S COUSIN RITA) WAS BORN IN JEANNIE AND LIN'S APARTMENT.Pp. 184-186:

The flat on Baum Street was also to be the birthplace of my cousin Rita.

Jeannie's sister Alma had married the Russian inventor/engineer (as you will recall) in a civil wedding in Paris, and we left them there struggling to promote the manufacture of his electric lamp. Repeatedly frustrated, in 1900 he was working as an engineer in an automobile factory, living nearby at #30 rue Hamelin, off Avenue Kleber. Russian friends were encouraging him to return to Russia. In preparation for this possibility, Alexandre arranged in midsummer for a second marriage ceremony, this one according to the rites of the Russian Orthodox Church so that Alma's status as his wife would be recognized there in Russia and her child (for she was then pregnant) would be accorded the privileges of Russian nobility.

But things were evidently uncertain for Alexandre, and it seemed best for Alma to return to the United States with her sister Helen Wright, who had left her children with grandparents and gone off alone for a "restorative" trip to Europe.

Russian visitors to the Paris Exposition — de Lodyguine's portrait honored in the Russian pavilion as inventor of the electric light — persuaded Alexandre that he really was needed in his native land and that he would be appreciated there. He now wrote Alma, begging her to return to Europe to go with him, but by this time she was too far advanced in pregnancy to travel. Therefore, upon assurance of renewed employment as engineer by Westinghouse, Alexandre again came to the United States. But upon arrival, the promised position was not forthcoming. So with lunch pail in hand he went to work in mill or factory.

During her confinement Alma was staying with Jeannie and Lin, and it was therefore in the flat on Baum Street that Margarita Alexandrevna de Lodyguine was born, January 28, 1901 and named for Alma's grandmother, Maria Margaretha, and (in the Russian manner) with the patronymic "daughter of Alexandre" as her middle name.

By June Alexandre secured employment with the National Storage Battery company and the Lodyguines removed to Cleveland. Two days later Margo Schmid married another Alexander by the name of Gow — a W. & J. man from little Washington, he also happened to be an engineer. With this, all four the Schmid daughters were then married.

______________________

The house on Dewey Avenue in Edgewood, PA, built for Jeannie and Lin, where a birthday party for Franz Schmid was held. Alma and Alexander Lodyguine were at the party. Alexander was at the time supervising the manufacture of cables for the then-new New York City subway.

The house on Dewey Avenue in Edgewood, PA, built for Jeannie and Lin, where a birthday party for Franz Schmid was held. Alma and Alexander Lodyguine were at the party. Alexander was at the time supervising the manufacture of cables for the then-new New York City subway.______________________

BY 1903, JEANNIE AND LIN, WITH A GROWING FAMILY, HAVE BUILT A LARGE HOUSE IN THE PITTSBURGH SUBURB OF EDGEWOOD. THERE IS A BIRTHDAY PARTY FOR FRANZ SCHMID, FATHER OF HELEN, ALMA, MARGO, AND JEANNIE. ALMA AND ALEXANDER LODYGUINE ATTEND THE PARTY. THEY ARE NOW LIVING IN NEW YORK WHERE HE IS SUPERVISING ELECTRICAL WORK FOR THE NEW SUBWAY THAT IS BEING BUILT, BUT HE IS IN PITTSBURGH IN CONNECTION WITH HIS WORK. THEY HAD RETURNED TO THE U.S. IN 1901 (AS WE LEARN IN THE NEXT VOLUME OF CHARLIE'S MEMOIRS). BY NOW THE LODYGUINES HAVE TWO DAUGHTERS, MARGARITA ("RITA") AND VERA, BORN IN 1901 AND 1902.Pp. 187-188:

Then there was a full-scale family reunion of the Schmids.

The occasion: Grosspapa Schmid's 74th birthday, December 4, 1903.

By this time the College Preparatory School had been closed because of the principal's failing health and strength, and Francis and Christine Schmid (was he not still Franz in the family and Xaver to his sister?) were making their home with daughter Margo, the Alec Gows then also living in Edgewood. Daughter Helen and Bob Wright were in nearby Wilkinsburg. And now Alma and Alexandre Lodyguine, who by then had moved to New York City, were able to come to Pittsburgh in connection with his work (engineer supervising manufacture and installation of the electric cables for the New York subways, soon to be opened). [ED. NOTE: SEE BELOW AND IN THE NEXT INSTALLMENT OF CHARLIE'S MEMOIRS.] And of course Jeannie and Lin were there, proudly hosts in their new home.

Then, in addition to all four of the Smith girls (as Lin sometimes spoke of them teasingly) and their husbands, there were also Grosspapa's sister Marie, now widowed (it was 37 years since he had accompanied her across the Atlantic to marry Pastor Walz) — and his brother-in-law Theodor Däuble, widower of his sister Rosina (Däuble the first of them to leave the Old Country for the New World).

The table was therefore set for twelve adults. But of course there were the children — the little cares of wedded bliss — two for each of the four sisters. I name them here:

Catharine Jane Wright (born Aug. 8, 1894) and Robert Francis Wright (May 22, 1896) — our cousins Jane and Robert.

Margarita Alexandrevna Lodyguine (Jan. 28, 1901) and Vera Alexandrevna Lodyguine (Dec. 29, 1902) — Rita and Vera.

Alexander Murdoch Gow, Jr. (Apr. 10, 1902) and John Lauden Gow (Sept. 8, 1903) — Bill and Jack.

Madeleine Virginia Cooper (March 10, 1899) and Elizabeth Pauline Cooper (Nov. 7, 1901) — my sisters Ginnie and Listy.

The formal names and dates come (with correction) from the crumbling page of the Schmid's family Bible, there also recorded the precise hour of each birth.

______________________

LODYGUINE'S EXHIBIT OF HIS INCANDESCENT LIGHT BULB AT THE UNIVERSAL EXPOSITION OF 1889 AT PARIS

". . . Alexandre de Lodyguine had become an international figure, and his work was prominent in International Expositions, such as that in Paris in 1889."It was in Paris that George Westinghouse met him and invited him to come to America as a consultant on electric lighting — and this brought him to Pittsburgh and into the Schmid family. . . " (- Cooper, above.)

BELOW AND IN THE NEXT PANEL ARE TWO CONTEMPORARY ACCOUNTS OF LODYGUINE'S EXHIBIT AT THE PARIS EXPOSITION OF 1889, THE REPORT OF THE U.S. COMMISSIONERS TO THE EXPOSITION AND A LIST OF PRIZE WINNERS AT THE EXPOSITION IN THE FRENCH JOURNAL L'ÉLECTRICIEN.

I. The U.S. Commissioners' Report:

At the International Exposition in Paris in 1889, the exhibition of Electricity contained displays of many kinds of lamp, including arc lights and incandescent bulbs, that were then being developed by many different inventors in various countries. One of the exhibitors, in the Russian section, was Alexander Lodyguine, whose display won a gold medal. The American Thomas Edison won a Grand Prize for his exhibit not just of his light bulb but of his whole manufacturing process.