Pantes anthropoi tou eidenai oregontai phusei. semeion d' he ton aistheseon agapesis: kai gar choris tes chreias agapontai d' hautas... ("Everyone by nature desires to have knowledge. A sign of this is our love of the senses; aside from their usefulness we love them for themselves..." --Aristotle, Metaphysics I.1) (Illustration: Athens in the nineteenth century, from an old engraving)

WELCOME TO MINERVA SYSTEMS |

|

Welcome to Minerva Systems, an enterprise created by Dr. Cora Angier Sowa. It is a product of the author's longtime search for connections between the aesthetic and the technological. It is also devoted to examining the continuity of influence of Greek and Roman Classical civilization, and to exploring how ancient insights can be applied to today's world. This site presents a selection of writings and photography by the author on some interconnected topics: Classical literature, computers and humanities, railroads and engineering, architecture, music, and movies, and the aesthetic appreciation of the marvels of the built environment. |

|

Athena - the Roman Minerva - was goddess of both intellectual wisdom and technical crafts. Accompanied by her owl, she was also protector of the city of Athens. |

|

|

|

|

|

While my professional career is in Greek and Latin Classics and in computers (interests that I combine in the field of digital humanities), I am also a lifelong railfan. I grew up in a house above the old Los Angeles Subway tunnel and trainyards, my father was Head Cost Analyst for the Los Angeles Division of the Southern Pacific, and my grandfather and uncle were civil engineers specializing in railway and highway bridges. I now live in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, overlooking the Hudson River and the historic tracks of the former New York Central, now CSX, Metro North and Amtrak. On the series of Web pages called "Cora Sowa's Right-of-Way: Railroad History of Cora Angier Sowa,", I display some of my collection of rail photos, with commentary about them. Pages called "Engineers (Civil, Electrical, and Mechanical) in the Family," add more archival material about various family members' contributions to the history of railroads and engineering. |

Click HERE for "Cora Sowa's Right-of-Way." Click HERE to read "Engineers in the Family." |

|

|

The view from my window, with the Lakeshore Limited passing by.

CLASSICAL QUOTATION OF THE MONTHPreserving the past, inspiring the future |

|

Every month there will be a new classical quotation in this space, appropriate to the season or to current events. Usually the quotations are from ancient Greek or Latin, with occasional forays into other sources, such as mediaeval Latin or ancient Near Eastern literatures. Previous quotations (beginning in September, 2004) are archived in "Archived Quotations of the Month" for each separate year. An index to all quotations for all years is located in the first Archived Quotations page. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Do you have a suggestion for a future Quotation of the Month? If so, send me your suggestions at casowa@aol.com. |

Women chatting at the public fountain (Athens, 6th cent. B.C., from a hydria, or water jug) What is today's conversation about? |

Quotation for April, 2022

April, a Month of Holidays: The Roman Vinalia |

Above: Grape harvest, mosaic from Cherchell, ancient Caesarea, a Roman colony in Mauretania, present-day Algeria. Illustration via Wikipedia.

A month of holidays

In this year of 2022, holidays of the major religions in the U.S. all fell on the same week — Easter, Passover, and Ramadan, with the Orthodox Christian Easter falling one week later. The Muslim Ramadan, which moves around the year, was a happy coincidence. Add to that in April we celebrate Earth Day, a time to recommit ourselves to taking care of our Mother Earth.

Spring festivals have been celebrated throughout human history, as the earth reawakens from its long winter sleep. This year that reawakening is particular signficant, as we finally seem to be escaping a two-year period of imprisonment by the COVID pandemic. In rural societies, spring is the time when crops are planted and the animals begin to give birth.

We will turn to Ovid's Fasti to see what festivals the ancient Romans celebrated in April.

The Fasti of Ovid

The Fasti or "Calendar" of the Roman poet Ovid (43 B.C. - 17 or 18 A.D.) was published in 8 A.D. It consists of six books, each describing festivals, astronomical information, and mythological or historical events for one month of the year, all told in poetry in the elegiac meter. Only the first six months, January to June, are included. Ovid perhaps originally intended to complete the other six, but information is inconclusive.

Like the saints' days of the Christian church calendar, Roman festivals were scattered throughout the year, some large and important, some minor, some rooted in Italy's rustic past, others imported.

Among the festivals celebrated in April we find that of Cybele, the Magna Mater, a Phrygian goddess brought to Rome during the Second Punic War against Carthage on the advice of the Sibylline oracle (the goddess was brought in the form of her cult object, a black meteoric stone). Also described is the Cerealia, in honor of Ceres, the goddess of grain (giving Ovid an excuse to tell the story of the rape of Persephone). There is also the Parilia, a ceremony of cleansing of sheep and shepherds, sacred to Pales, a divinity who was their patron. The Robigalia, another agricultural festival, offered prayers to Robigo, a personification of rust or mildew, a disease of grain. A festival devoted to wine was the Vinalia, which is the subject of our Quotation of the Month.

The Vinalia Urbana and Vinalia Rustica

There were two festivals called the Vinalia. The Vinalia Rustica was held on August 19. It celebrated the grape harvest and the wine pressing. Unfortunately, we don't know how Ovid would have described this event. as the Fasti stops at June. The Vinalia Urbana was celebrated on April 23 (just two days after the Parilia, which came on April 21). Also called the Vinalia prima, or "First Vinalia," it was held to bless and sample the wine from the previous fall harvest.

The two divine patrons of the Vinalia Urbana were Venus, as patroness of the "profane" wine for ordinary drinking, and Jupiter, patron of the strongest, purest, sacrificial grade wine. On the day of the festival, "common girls" and prostitutes would go to the temple of Venus Erycina to offer mint and floral tributes, to pray for the gift of charm and witty conversation. Venus Erycina was another imported goddess, the Punic Astarte, whose idol was captured at Eryx, in Sicily. She had two temples, one on the Capitoline Hill, where she was worshipped by elite and respectable matrons, and another, outside Rome's sacred boundary, near the Colline Gate, which was frequented by lower class women.

Ovid describes the women's worship of Venus, explaining, in a tongue-in-cheek way that the goddess "prefers to be worshipped in the city of her descendants," in reference to her being the mother of Aeneas, mythic progenitor of the city of Rome. This passage forms our Quotation of the Month. In the part following our quotation, he describes Jupiter's role in the festival, telling how Aeneas and Turnus competed for the hand of Lavinia, daughter of the Latin king Latinus. Turnus called for aid from the Etruscan Mezentius, who pledged wine from the next vintage to the king. Aeneas pledged the wine instead to Jupiter, who helped Aeneas win the fight with Mezentius, and thus the hand of Lavinia.

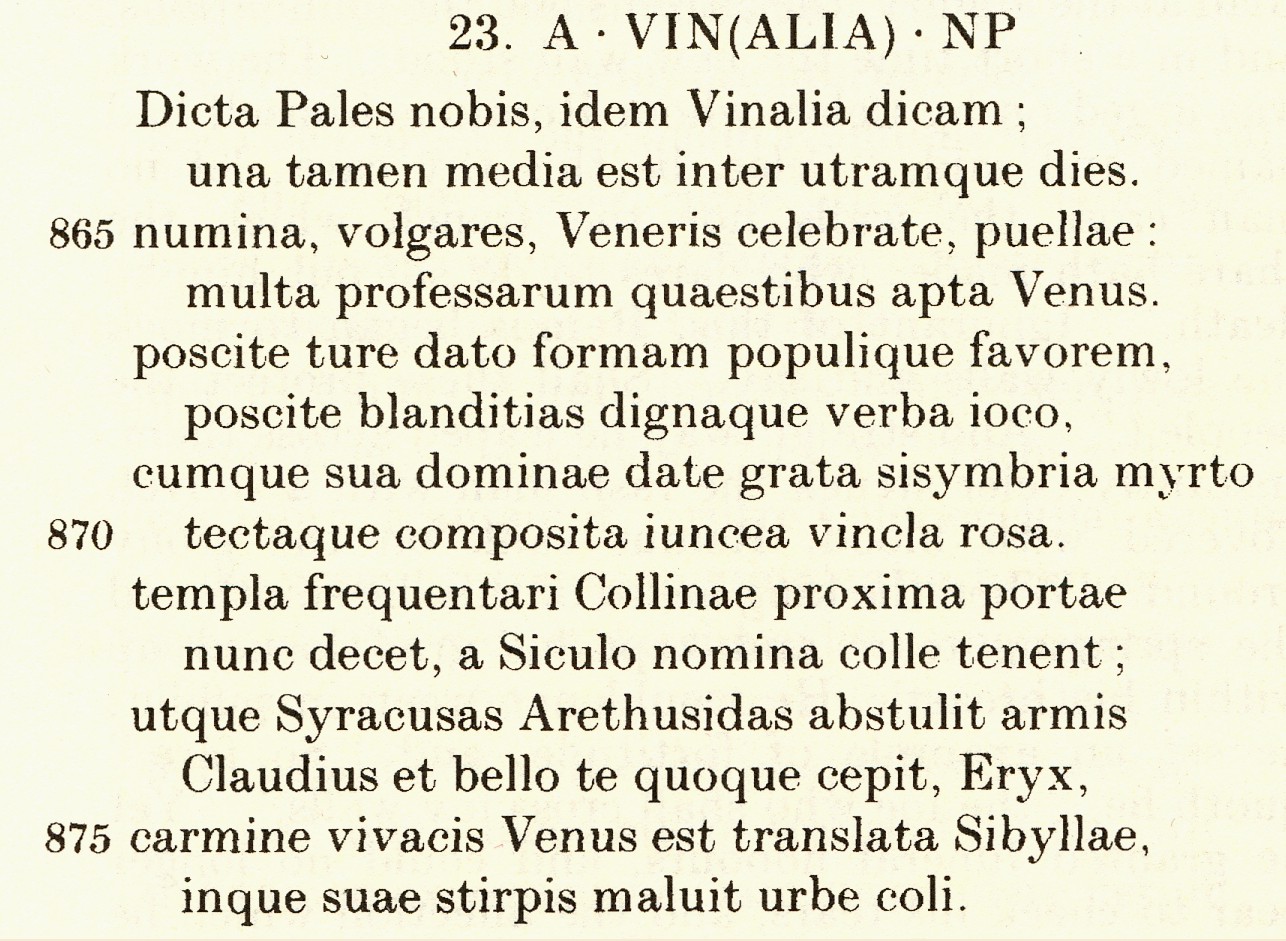

Quotation of the Month, Ovid Fasti Book 4 vv. 863-876

For our Classical Quotation of the Month, we bring you, in Latin and English, the first part of Ovid's description of the Vinalia Urbana, describing the offerings to Venus. The text is that of the Loeb edition, corrected second edition, edited by James George Frazer, revised by G.P.Goold. The translation is my own.

Ovid Fasti 4.863-876

|

At the Vinalia, common women make offerings to VenusThere is but one day between the two. Girls of the common sort, celebrate the divinity of Venus; Venus is suited to the earnings of your profession. Offer incense and ask for beauty and for popular favor, ask for the gift of flattery and joking words. Give the Mistress the wild mint that pleases her, along with her very own myrtle, and bundles of reeds covered in clustered roses. Now is the time to crowd her temple, next to the Colline gate, the one that takes its name from the Sicilian hill. When Claudius captured Arethusian Syracuse by force of arms and also took you, Eryx, in war, Venus, too came to Rome, according to the long-lived Sibyl's prophecy, preferring to be worshipped in the city of her descendants. . . . |

Treading grapes for wine. Rome, 2nd half of 1st century A.D. Ancient Roman reliefs in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow. Photo by Shakko, 2009, via Wikipedia.

Archived QuotationsEarlier quotations, appropriate to the seasons or to current situations as indicated, are available in the pages of "Archived Quotations." The index of all archived quotations, formerly in this space, having grown very large, has now been moved to the head of the main Quotations page. The quotations themselves now occupy separate pages for each year, but all can be accessed from the index on the main Quotations page. |

MINERVA participation in the Chicago Colloquia on Digital Humanities |

The Chicago River, from the Michigan Avenue Bridge, January, 2008. (Photo by C.A. Sowa.)

CHICAGO COLLOQUIA ON DIGITAL HUMANITIES AND COMPUTER SCIENCE

Since their inception in the fall of 2006, I have been attending the Chicago Colloquia on Digital Humanities and Computer Science (DHCS), held at a rotating group of universities around Chicago. These Colloquia now draw participants from all over the world, who present projects covering many fields, including such interests as visual arts, archaeological reconstruction, musical composition, literary criticism, social trends, popular culture, history, and many fields yet to be discovered. Of the projects I have submitted under the name of Minerva Systems, a couple have been presented as poster exhibits. Others I have informally circulated among the participants. But whether one is presenting a paper or simply taking part in discussions, the Colloquia offer an opportunity to exchange a wealth of ideas. Workshops and smaller discussion groups, too, are well worth while.

For information about the Colloquia, visit the DHCS Web site at "http://chicagocolloquium.org". Information about all previous Colloquia (2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011) can also be accessed from there.

Previous DHCS Colloquia and MINERVA offerings:Click on the buttons on the right to read the MINERVA presentations. 2006The theme of the first Colloquium (2006)was "What to do with a Million books," posing the problem that, now that all the world's libraries have been put in digital form, what do we do with them? MINERVA Systems presented a demonstration showing the capabilities of MINERVA as a set of tools for carrying out a project to study a work of literature, using digital methods. The first Colloqium was held at the University of Chicago at its Hyde Park Campus. 2007The emphasis of the second Colloquium (2007) was on using digital materials in a collaborative environment, and on discerning what studies are better undertaken by using digitized versions of materials such as images and text than by using the original non-digitized sources. The MINERVA demonstration for 2007 highlighted new additions to the Systems Analysis Tutorial/Project Planner, which aid the user in steps to planning and carrying out a project in an organized way. These techniques are adapted from the commercial and scientific fields, where teams of persons who may be working in distant locations must coordinate their efforts. The second Colloqium was held at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. 2008The theme of the third Colloquium (2008) was "'Making Sense'- an exploration of how meaning is created and apprehended at the transition of the digital and the analog." "Sense-making" is a field concerned with finding meaning in vaguely defined material. As usual, this third Colloquium brought together a terrific group of diverse scholars and students working in different areas of computer applications. These included not only literary and sociological studies, but such inventive applications as a study of different musical genres (country, gospel, blues, hip hop, heavy metal, etc.) to see which body parts (head, heart, hand, etc.) are mentioned most often, and three-dimensional recreations of archaeological and historic sites, including a study of pedestrian traffic patterns in an ancient Turkish town destroyed by Cyrus the Great. Minerva Systems submitted a paper to the third Colloquium, "A Bridge Across the Culture Gap: Build Your Own Project Using the Minerva System for Study of Literary Texts", which was given as a handout to all who were interested. Additions to the MINERVA System emphasized the need to serve "the great unserved middle," between the Luddites and the Rocket Scientists, of scholars and students, who would like to be introduced to elements of logical analysis and computerized methods. The third Colloqium was held at the University of Chicago. 2009The theme of the fourth Colloquium (2009) was "Critical Computing", seeking to explore how productive research collaborations between computer scientists and humanists can be most effective.

The fourth Colloquium was held at the Illinois Institute of Technology. 2010The theme of the fifth Colloquium (2010) was "Working with Digital Data: Collaborate, Curate, Analyze, Annotate." Emphasized in particular were papers or poster sessions about annotation, scholarly crowdsourcing, and challenges of human/computer interaction. How to create better texts from OCR may be a problem in which new forms of human/computer interaction hold particular promise. Minerva Systems circulated a paper titled "BUILD-A-BEAR" RESEARCH PLANNING: CLARIFICATION OF DEFINITIONS AS THE KEY TO CHOOSING OR WRITING PROGRAMS, a discussion of analytical methods designed to help the scholar/user analyze his or her own research problems sufficiently to choose or design an appropriate computer solution. The fifth Colloquium was held at Northwestern University. 2011The sixth Colloqium (2011) was held at Loyola University at its Water Tower Campus. Minerva Systems was again in attendance. 2012The seventh DHCS Colloquium was held at the University of Chicago at its Hyde Park campus. Minerva attended. 2013The eighth Colloquium, attended by Minerva, was held at De Paul University, near Lincoln Park. |

Read the MINERVA demos and handouts from the 2006, 2007, 2008, and 2010 Colloquia.Click on the buttons below to see the complete MINERVA handouts.

|

The Reliance Building, at State and Washington Streets in Chicago, January, 2008. (Photo by C.A. Sowa.) The Reliance Building, like the MINERVA System, was built on principles of modularity and extensibility.The Reliance Building, an incredible little jewel in the middle of Chicago's Loop, was not all built at once. When the developer acquired the site in 1882, it was occupied by a five-story building. The leases on the lower two floors expired in 1890, those on the top three in 1894. So, as the first leases expired, the architects Daniel H. Burnham and John Wellborn Root demolished the first two floors, and, jacking up the top three storeys, replaced the demolished floors with the first two floors of the new building. When the remaining leases expired, the top floors of the old building were demolished, and replaced with new floors, designed by Charles Atwood, Root having died. The number of floors eventually grew to fifteen, made of identical structural modules and clad in graceful terracotta, giving the building the perfect proportions that it has today, somewhat overwhelmed, unfortunately, by the gigantism of the surrounding modern buildings.

Today, the Reliance Building, after years of neglect (shabby but still showing her noble "bones"), has been reborn as a boutique hotel, called the Burnham, with an excellent restaurant, the Atwood, on its ground floor, the names being chosen as an homage to its architects.

THE MINERVA SYSTEM FOR STUDY OF LITERARY TEXTS, INTRODUCED A IN SELF-STUDY CD The Loom of Minerva: An Introduction to Computer Projects for the Literary Scholar |

|

Read about it!

My thanks to all those who have reviewed and used my self-study CD course on using computers and quantitative methods in the study of literature, The Loom of Minerva: An Introduction to Computer Projects for the Literary Scholar, and my thanks to those who continue to give me comments.

You can read Chapter 1, "A Guide to the Labyrinth: The Problem and Its Solution" on this Web site. (Note: this chapter now describes a greater variety of ways to structure a project, e.g., top-down, bottom-up, etc. It will continue to be revised.) You can also see images from two demonstrations of the MINERVA System, from 2006 (emphasizing individual applications programs), given at the First Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities at the University of Chicago and 2007 (emphasizing new project planning programs) given at the Second Chicago Colloquium on Digital Humanities at the Northwestern University.

The MINERVA System

The MINERVA System for Study of Literary Texts is a set of tools, some automated, some not automated, for planning and carrying out a project in literary study. Methods of Systems Analysis, borrowed from the scientific and commercial world, are adapted to the study of literature. This methodology emphasizes the use of diagramming techniques and modular design, offering a way to construct a project as a set of units or modules that can be worked on separately and moved around without disturbing the whole. A project is defined as an enterprise that has a goal and an organized way of achieving that goal.

The Loom of Minerva combines the methods of Systems Analysis with the insights of traditional belles-lettres literary criticism. All analysis takes as its point of departure the value of the piece of literature itself to the critic and the reader, as well as the historic, social, or aesthetic qualities attached to it. These alone confer significance on any work of scholarship. Examples grow directly from study of various works of literature, from Vergil to Coleridge to Baudelaire to Victor Hugo to Edna St. Vincent Millay and Gertrude Stein, and works of criticism from Sainte-Beuve to Swinburne to Gertrude Stein (criticizing her own work).

Emphasis is placed on analyzing the language of criticism itself, analyzing exactly what we mean by such terms as "beautiful," "ugly," "pompous," "like a spring garden," etc. By defining our terms with an exactness that can be quantified, we learn to give precision to our thoughts, whether using a computer or not.

What is in The Loom of Minerva

The CD contains both a set of narrative chapters and a set of programs, called the MINERVA System for Study of Literary Texts. The narrative chapters explain and amplify the programs, and the programs illustrate the chapters. The programs are provided in both executable form and source code, to satisfy both non-programmer scholars and programmers who want to play with the code.

- The programs.

The programs are in two groups, The Tutorial in Systems Analysis and the MINERVA Program Suite. The Tutorial in Systems Analysis takes the student through the steps to plan and design a project, beginning with the Selection of a Topic, going through the activities of drawing hierarchical and flow charts, and continuing to the final Evaluation of Results. The screens are interactive, so that the student can practice designing his or her own project.

The MINERVA Program Suite is an interactive suite of programs designed for use by scholars and critics of literature. These programs, which can be used with texts of English, Classical, or other literatures, currently contains sixteen programs: eight to perform different types of literary analysis, and eight "OwlData" programs that the scholar can use to create or adapt data for the analytical programs. Currently available are programs to make concordances, search for words and cooccurring words, do statistical studies, perform cluster analysis, and compose original paragraphs. Developed in modular fashion, MINERVA is intended to be expandable, so that in the future more modules can be added to do more things. The latest to be developed is a program to perform cluster analysis based on the program described in Sowa and Sowa "Thought Clusters in Early Greek Oral Poetry."

- The narrative chapters

The narrative chapters can be read like a book, or they can be entered directly from the programs by clicking on links on the screens.

The first four text chapters of The Loom of Minerva introduce the MINERVA System. They demonstrate the steps for planning and developing a project, and provide many literary examples for using the programs. Historical chapters of The Loom of Minerva analyze projects past and present, that have used computers and other mechanical devices in the study of literature (including the Eureka Machine for composing Latin hexameters). Also described are works of literature that were inspired by machines, like the short story "Moxon's Master" by Ambrose Bierce (1842-1914), in which a chess-playing robot murders its inventor. Four final chapters of the book are for techies only: a programming manual of Visual Basic, using literary examples, for those gung-ho readers who want to understand the arcana behind the MINERVA programs included with the book.

MINERVA stands for Model INteractive Engine for Recognizing Verbal Artifice.

Advantages of the MINERVA System

The MINERVA programs do not require the use of data that is in a proprietary format. They use plain ASCII text, such as that downloaded from the Internet. The OwlData programs can be used to put downloaded or scanned text in the correct format for the MINERVA programs. The mathematics and statistics used are fairly elementary, such as can be understood as an introduction to basic concepts of what the computer and quantified methods can do. The programs are open-source, as they are intended to be extensible.

For more information:

If you are interested in finding out more about the Loom of Minerva or the MINERVA System, contact me at casowa@aol.com.

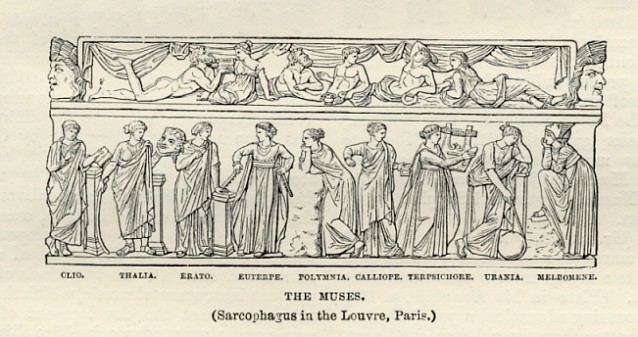

Historical chapters of The Loom of Minerva describe projects using the computer in the study of literature, including the author's Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns (see below). One of the thematic elements analyzed is "Maidens Dancing and Picking Flowers." |

A VICTORIAN COMPUTER LIVES AGAIN!WATCH A REPLICA OF CHARLES BABBAGE'S ENGINE IN ACTION |

Reconstruction of one of Babbage's engines at the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California. Click on the picture to watch it in action. (Photo by J.F. Sowa).

Charles Babbage's Difference Engine and Analytical Engine

Charles Babbage, prolific Victorian inventor, is most famous for two of his inventions, the Difference Engine (1812) and the Analytical Engine (1833), which are perhaps the truest forerunners of the modern computer. The Difference Engine, a mechanical device of rotating gears, was designed to automatically generate mathemetical tables. It was called the Difference Engine because it was based on the principle of computing the differences between successive values of an expression, then the difference between the differences. Versions of the Difference Engine were eventually built and used, but Babbage himself dropped work on it to pursue his real dream, the Analytical Engine. The Analytical Engine was, or would have been, the first "real" computer, capable of performing any kind of mathematical operation, and able to be "programmed," that is, to perform a sequence of operations without human intervention, and to choose, when necessary, between alternative paths of action. It was to be powered by steam, and programs were to be entered into the machine by means of punched cards, an idea borrowed from the then-new Jacquard power looms. Babbage, sad to say, was never able to complete the Analytical Engine.

Ada, Lady Lovelace, "the world's first programmer"

Babbage's collaborator on his Engines was one of history's most remarkable women, Ada, Lady Lovelace, daughter of the poet Lord Byron. These lines from Childe Harold's Pilgrimage are thought to be addressed to her:

Is thy face like thy mother's, my fair child, |

A gifted mathematician in her own right, Ada worked with Babbage until her untimely death in 1852 at the age of 36. In 1842, the Italian engineer Luigi F. Menabrea published a description, in French, of Babbage's Analytical Engine. Lady Lovelace translated Menabrea's article into English, expanding it with commentary so extensive that her "Notes upon the Memoir" are virtually an original work. She provides detailed directions for using the machine to calculate answers to mathematical problems, leading modern writers to call her "the world's first programmer." Her words relate computing to other artistic endeavors:

We may say most aptly that [Babbage's] Analytical Engine weaves algebraical patterns just as the Jacquard-loom weaves flowers and leaves.

A Babbage Engine in London and California

In 1985, the Science Museum in London set out to build a working Difference Engine No. 2, based on Babbage's original designs. It was completed in 2002, and is on public display at the Science Museum. An identical Engine, completed in 2008, is presently on loan to the Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California, where it is on display until May, 2009. Read more about this recreated machine at the Computer History Museum Web site.

Click here or on the picture below to watch the Babbage engine in action, in a video taken by John F. Sowa.

Reconstruction of one of Babbage's engines, detail view. Click on the picture to watch it in action. (Photo by J.F. Sowa).

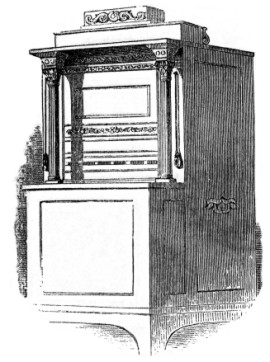

Read about the 1845 Eureka Machine for Composing Hexameter Latin Verse

Another Victorian machine which could be called an early special-purpose

computer was the Eureka machine designed by John Clark in 1845 for automatically

composing Latin hexameter poetry. It still survives, in a museum in Somerset,

England. Click here to read about it.

TRADITIONAL THEMES AND THE HOMERIC HYMNS IS AGAIN IN PRINT. SELECTIONS AVAILABLE FOR FREE READING ON THIS SITE |

One of the mythic themes analyzed in Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns is the Epiphany of a God. |

Book: Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns

Cora Angier Sowa is the author of Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns published by Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Mundelein, IL (1984).

The book, out of print for a while, is again available by "on-demand" production. Contact the publisher for information.

New selections are available on this Web site for free reading. You can read Chapters 1 ("Introduction") and 10 ("Conclusion: the Place of the Hymns in the Ancient Greek Oral Tradition"), Appendix I ("Outlines of Themes Identified in the Hymns"). You can also see diagrams of the themes as they appear in the Hymns.

Article: "Thought Clusters in Early Greek Oral Poetry"

An article, by Cora Angier Sowa and John Sowa, describes in detail

the quantitative and mathematical methods used on the computer to

identify thematic elements in Hesiod and the Homeric Hymns.

Material from this study was later integrated into into the more

comprehensive Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns. Click on

"Thought Clusters in Early Greek Oral Poetry".

A version of the CLUMP cluster analysis program used to identify thematic

repetitions is now also being integrated into the MINERVA suite of programs

in the self-study CD The Loom of Minerva.

"Verbal Patterns in Hesiod's Theogony" |

In orally composed poetry like Homer's Iliad and Odyssey, and Hesiod's Theogony and Works and Days, there was no written text (the alphabet being barely known at the time, around 750 B.C.). The bard, like a jazz musician, recomposed his story each time (to a melody now lost to us), using stock phrases or "formulas" and repeated scenes. Since the story was enjoyed not by reading but by hearing it, there were no punctuation marks or chapter headings to tell listeners where they were in the narrative or its episodes. The skilled singer used, instead, repeated words and phrases to serve as "oral punctuation" to articulate the story and provide emphasis for important themes and concepts.

Reissued here is my article Verbal Patterns in Hesiod's Theogony, which explores the use of verbal repetition in Hesiod's tale of the origins of the gods.

The Eureka Machine for Composing Hexameter Latin Verses (1845) |

We think of computers as being very modern, although calculating machines and computer-like devices have been around for a long time. In particular, we think of using such a machine to do such non-scientific tasks as composing poetry as a modern concept. But in 1845, John Clark built the Eureka Machine for Composing Hexameter Latin Verse. It still exists in a museum in England. Read about the Eureka Machine and read the original description of it from the Illustrated London News of July, 1845.

There is more about early computers and their mechanical ancestors in the self-study CD The Loom of Minerva: An Introduction to Computer Projects for the Literary Scholar, described above.

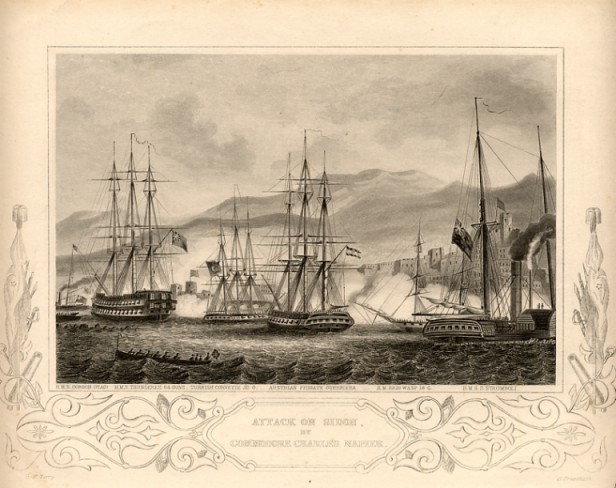

Ships named Minerva |

Classically named ships have a long tradition. Illustration: "The PHOENIX and the ROSE, engaged by the ENEMY'S FIRE SHIPS & GALLEYS, on the 16th Augt 1776. Engraved from the Original Picture by D. Serres, from a Sketch of Sir James Wallace's." Lithograph by G. Hayward for D.T. Valentine's Manual 1776. |

"Minerva" has long been a popular name for ships. There are cruise ships named "Minerva," including Greek vessels whose owners chose that name as a synonym for their own city patroness Athena. Warships named "Minerva" have graced the navies of Europe from the time of Nelson and Napoleon to the present, whether British "Minerva" or French "Minerve."

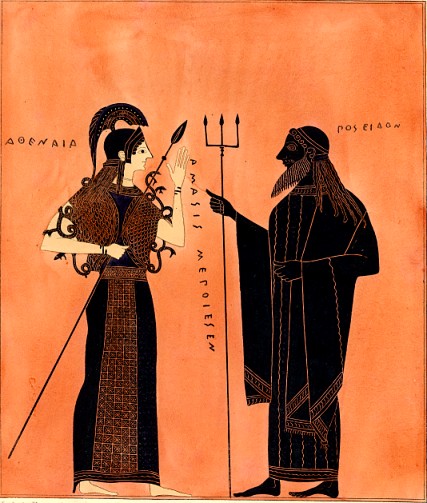

It is an interesting choice, considering that Athena, with her gift of the olive, defeated Poseidon, lord of the sea, with his gift of the horse, in the contest to be patron deity of Athens. (See the depiction of Athena and Poseidon below.)

The name "Minerva" for a British warship belongs in the splendid tradition of naming vessels after names from Classical history and mythology. Along with names like "Invincible," "Audacious," "Irresistible," "Insolent," "Victory," and "Dreadnought," we find "Gorgon," "Phoenix," "Achilles," "Apollo," "Dryad," "Endymion," "Hector," "Helicon," "Medusa," "Meleager," and, famously, "Arethusa." The most famous ship named for the Sicilian nymph Arethusa was known for her victory over the French "Belle Poulle" in 1778. Training ships for over a century inherited the name, one after the other.

A frigate "Minerva" participated in the Battle of Cape St. Vincent against the navy of Napoleon on February 14, 1797. The marine painter Thomas Buttersworth (the elder) painted a portrait of "Minerva" in 1810, and the "Minerva" Pub in Hull, England (built in 1831) uses the frigate's symbol, the owl, on its sign. Of course, some ships have been named "Athena" and "Poseidon," too; there was a movie about such a ship called The Poseidon Adventure.

There is a further connection between ships and this Minerva Systems site. In the self-study CD The Loom of Minerva (described above), an analysis of Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is used as a case study to demonstrate methods of Systems Analysis and computer techniques.

A feminist note on the gender of ships: Because of the living qualities of ships, I like to refer to a ship as "she" rather than "it." While some may compare a vessel to a woman because of the supposedly capricious nature of both (although there seems nothing wrong with an occasional playful moment), I think that this view overlooks other qualities. Ships, like women, are beautiful, swift, intelligent, and powerful. I am glad to acclaim them as my sisters!

"Attack on Sidon by Commodore Charles Napier." The battle took place in September, 1840. Sir Charles Napier was a lineal descendant of John Napier, inventor of Napierian logarithms, whose mathematical insights led to the invention of the slide rule, itself an ancestor of the modern computer. |

Signed vase painting by the Athenian potter/painter Amasis (6th cent.

B.C.), depicting Athena and Poseidon. The two figures are labeled

ATHENAIA and POSEIDON. The inscription down the middle reads

AMASIS MEPOIESEN ("Amasis made me"). Amasis may well have been

African. (Illustration from a lithograph by Kaeppelin et Cie., ca. 1840.

The actual vase is in the Cabinet des Médailles, Bibliothèque

Nationale de France, Paris.)

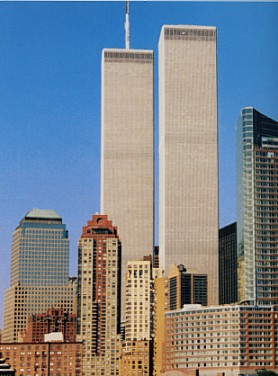

Myths of landmarks: Pennsylvania Station and Times Square as centers of the universe, the World Trade Center as a Mythic Place |

The World Trade Center was a sacred place long before it was blown up by terrorists. Lower Manhattan was the sacred land of the Lenape Indians, who made their community and buried their dead there. The modern World Trade Center, with its iconic double-towered shape (a nation's gateway, a cosmic tuning-fork?) was a symbol to the world of universal aspirations and longings. As a center of communications (with its towering antenna) and of transportation (as a hub of rail transportation) it had the mana or spiritual power of the crossroads, the traditional meeting place watched over by the gods of trade. |

Essays and reviews on building and architecture

Among the selections on this site is the previously published "Holy Places", a study of myths of landmarks. In addition, there is an epilogue to that essay, on "The World Trade Center as a Mythic Place". This piece continues the author's interest in relating ancient ideas to things that we care about in the modern world.

You can also read two of the author's previously published book reviews on architecture, on Alison Sky and Michelle Stone's Unbuilt America and Albert Mehrabian's Public Places and Private Spaces.

THE MUSIC PAGE |

The author plays the harp for an appreciative audience (handsome cat-about-town Feliz Sowa). Music has always been part of my life. I have played the harp since I was in junior high school, and have played both solo and in groups. Even before that, as a child, I invented my own instruments, a "rubber band guitar" made by stringing rubber bands of different sizes around the bottom part of a cigar box, and a "milk can marimba" (self-explanatory). People tend to think of the harp as a beautiful but gentle instrument, on which to play graceful glissandos, but I prefer to think of it as the "wild harp" of the warrior. The March of the Men of Harlech is one of my favorite pieces to play. Since 1977 I have been a member of the Percy Grainger Society, in White Plains, New York, an organization dedicated to preserving the home and archives in White Plains, New York of Percy Grainger -- composer, piano virtuoso, collector of folk songs, and inventor of an early mechanical music synthesizer. I am an emerita member of its board of trustees. In 2001 I created the original Grainger web site. I maintained this site until 2018, when it was superseded by a new, interactive site. Read the original Grainger web siteThe contents of the original Grainger web site can be read here. Published article on the influence of the ethnomusicologist Natalie Curtis Burlin on the music of Percy GraingerMy article Natalie Curtis, Busoni, and Grainger first appeared in The Grainger Journal, Vol. 17 No. 2, January 2022. It is reproduced here with the permission of the Percy Grainger Society. It is based on an earlier blog post written for the Percy Grainger web site which appeared on February 24, 2020. Blogs written for the Percy Grainger web siteI have also written several blogs for the current Grainger Society web page. They are reproduced here:

|

About the Author |

The author is an aficionado of many kinds of transportation, including railroads, ships, and airplanes. Here I am "at the wheel" of the ferryboat Eureka (rebuilt in 1923 from the 1890 freight-car ferry Ukiah) at the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park. |

Cora Angier Sowa has combined humanities and technology for many years. She has a BA in Latin and an MA in Classics from the University of California, Los Angeles, and a PhD in Classical Philology from Harvard University. She spent a year studying archaeology at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. She taught Greek and Roman literature and history at Mt. Holyoke, Vassar, and Brooklyn Colleges. For a number of years, she was a programmer/analyst at Chemical (now Chase) Bank in New York. She has taught classes in computers and humanities at the College of Staten Island and at St. John's University in Queens, New York. She served twice on the Committee on Computer Activities of the American Philological Association, once as chairperson of the committee. She was the recipient of a Fulbright Scholarship (for study in Greece) and of a grant from the American Council of Learned Societies (for work on computers and ancient Greek literature).

In addition to the book Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns (described above), Dr. Sowa has published articles and reviews on Classics and on the mythology of architecture and motion pictures.

A harp player, she is also an emerita member of the board of trustees of the Percy Grainger Society, and created its original web site, as described above, on The Music Page.

A lifelong railfan, Dr. Sowa is a member of the New York Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society and is on its Board of Directors. She is National Representative for the New York Chapter and is on the Advisory Council of the national organization. She is also a member of the New York Railroad Enthusiasts and of the Railway and Locomotive HIstorical Society.

Dr. Sowa lives in Croton-on-Hudson NY, and in New York City, with her husband, Dr. John F. Sowa, an expert in Artificial Intelligence and computer design, and several cats.

All selections on this site, unless otherwise identified, are copyright by Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

On this Web site, you are visitor number:

Last Modified: