These are quotations for the year 2005. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

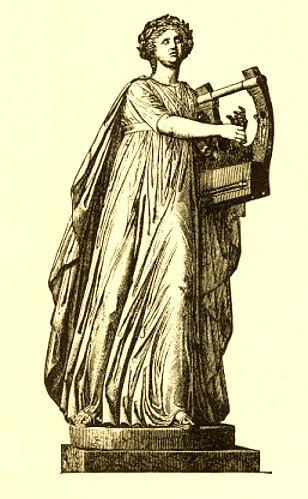

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2005, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2005 |

Below are quotations for the year 2005. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2005

Click on a link to read each quotation

2005

- December '05 A quotation on sacred trees for the Winter Solstice, Christmas, and other winter holidays from Horace (on the dedication of a pine tree to Diana).

- November '05 A quotation (and pictures) for Halloween, El Dia de los Muertos, and Thanksgiving; Ovid on the Lemuria -- a kind of Roman Halloween -- and some artesian wells in South Dakota.

- October '05 A quotation for Columbus Day from Horace on the perils of a sea voyage.

- September '05 A quotation from the Roman satirist Juvenal suggested by Hurricane Katrina. (After a disaster, the rich get richer and the poor are left homeless.)

- August '05 A quotation for the dog days of summer (from Hesiod's Works and Days, on sex-crazed women and weak men),

- July '05: a patriotic quotation for the Fourth of July (Livy on Cincinnatus, role model for the Founding Fathers of the U.S.),

- June '05: summer vacation (Horace on enjoying life and being silly),

- May '05: the Kentucky Derby (Pindar's victory ode for King Hieron's horse Pherenikos),

- April '05: Income Tax deadline (April 15) (Hesiod on honest work vs. corruption),

- March '05: the first day of spring (Vergil and Tibullus),

- February '05: Valentine's Day (Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite),

- December '04, January '05: Saturnalia and the start of winter (a festive quotation from Catullus and a chilly one from Hesiod),

A quotation about sacred trees (from Horace) for the Winter Solstice, Christmas, and other winter holidays, December 2005 |

Photo by C.A. Sowa

Evergreens and oaks

Trees are sacred in many religions. Evergreens, especially in our northern climate, are cherished for their green needles that remain, with their message of survival, when all else is bare and snow-covered. The "Christmas Tree" of Christians is a continuation of the old custom. (By the way, the German "O Tannenbaum" does NOT mean "O Christmas Tree" but "O Fir Tree." English, unfortunately, does not have a two-syllable word for "fir" or "pine" to translate the German Tanne. The words O Tannenbaum, o Tannenbaum,/ wie treu sind deine Blätter!/ Du grünst nicht nur zur Sommerzeit,/ Nein auch im Winter, wenn es schneit are correctly translated "O fir tree, O fir tree/ how true are your leaves!/ You are green not only in summertime,/ no, also in winter, although it snows.") The majestic, mysterious fir tree is aptly associated with Christmas, one of many festivals that occur at the time of the Winter Solstice. It is a bringer of hope at the time of the shortest day, when the sun and its warmth seem farthest away. The birth of a baby under harsh circumstances, as Jesus' birth is depicted, is likewise a hopeful sign. A similar optimistic message in conveyed by the festival of Hanukkah, celebrating the miraculously burning lights, which, with only enough oil to last one day, burned for eight days. Even the much-maligned "commercialism" of the holiday season is a sign of optimism and energy -- and for merchants and vendors, a chance to make up for a dismal year. Mercury, god of commerce and communication, flourishes.

Oak trees have also been revered, and many myths have grown around them. In Dodona in Greece, the grove of oaks sacred to Zeus was consulted as an oracle. The oaks spoke, and Zeus made his will known through the whisperings of their leaves.

Horace dedicates a pine tree to Diana

In our quotation of the month, the Roman poet Horace dedicates a pine tree at his Sabine farm to Diana, with the promise of a yearly sacrifice of a boar (the Roman version of our holiday pork roast!). He celebrates Diana as the protector of young women in childbirth, and calls her triformis, "triple-formed" -- Diana on earth, Luna in the sky, and Hecate in the Underworld. Below is his poem, in the original Latin and in translation.

Montium custos nemorumque, Virgo,

quae laborantes utero puellas

ter vocata audis adimisque leto,

Diva Triformis,

imminens villae tua pinus esto,

quam per exactos ego laetus annos

verris obliquum meditantis ictum

sanguine donem.______________________________________________________

Guardian of mountains and groves, Virgin

who hears the prayers of girls laboring in childbirth,

when thrice they call you, and rescues them from death,

Triform Goddess,

Let this pine tree hanging over my villa be yours.

To it gladly at each year's end

may I offer the blood of a young boar practicing his sideways thrusts

as a sacrifice.--Horace Odes III.22

Photo by C.A. Sowa.

A quotation (from Ovid) and some pictures for Halloween and Thanksgiving, November 2005 |

Toy church and skeleton girl for the Dia de los Muertos

(purchased in Olvera Street, Los Angeles), photo by C.A. Sowa.

Fall welcomes both ghosts and harvests

November is bracketed by two holidays, Halloween and Thanksgiving. While in their modern form they are distinctly American, both have roots that go back to old festivals of the dead and of the harvest. Halloween, among other origins, can be traced to the Celtic festival of Samhain, celebrating the return of the herds from pasture, but involving the return of the dead to revisit their homes. It also included rites of harvest and the reaping of the last sheaf, as well as rituals connected with fire and divination. In Mexico and in Mexican communities in the U.S., November 1 and 2 (All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day) are celebrated as the Dia de los Muertos ("Day of the Dead"), which combine Catholic, Aztec, and other Mexican Native customs, celebrated with pastries, candies, and little toy scenes in the shape of skeletons disporting themselves. Family members hold picnics at the cemetery, so that dead family members can enjoy them, too.

The ancient Roman world was peopled with many kinds of ghosts, appeased at various festivals. The Parentalia (13-21 February) honored the dead of each family. The Lares were also, apparently, spirits of dead family members, associated with crossroads, honored at the festival of the Compitalia, but a Lar familiaris also had a shrine with the Penates, or gods of the pantry, within each house. Larvae (spectres) were scarier, as were Lemures (ghosts). The Lemuria (9, 11, 13 May), a ritual for feeding and propiating the angry and sinister lemures, is described by Ovid, in the passage translated below.

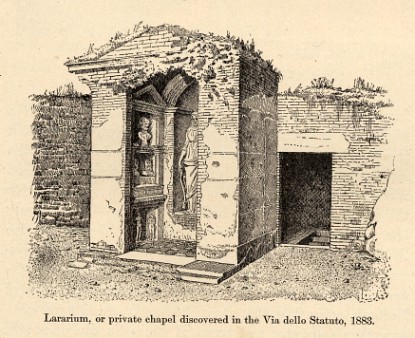

Illustration from Rodolfo Lanciani, Ancient Rome in the Light of

Recent Discoveries, 1898.

A ritual of the Lemuria is described by Ovid in the Fasti ("The Yearly Calendar," in which, unfortunately, only the first six months are described). Black beans are thrown behind the back for the ghosts to pick up.

After that, when Hesperus has thrice revealed his lovely face,

and thrice the defeated stars have given place to Phoebus,

there will be the rites of the ancient religion, the nocturnal Lemuria:

They will provide sacrifices to the silent shades.

The year was once shorter, and men did not yet know pious February,

nor did you, leader of the months, bi-form Janus, exist.

Yet they brought their gifts to the ashes of the dead,

and the grandson paid his respects at the tomb where his grandfather was buried.

The month was May, for the maiores [ancestors] named,

which even now preserves part of the old custom.

When it is midnight, offering silence to sleep,

and the dog and the colorful birds have become still,

he who is mindful of the old rite and fearing of the gods

arises (his twinned feet wear no bindings),

and he gives a sign, holding his thumb in the middle of his closed fingers,

lest an insubstantial shade meet him, while he remains silent.

When he has washed his hands pure in the waters of a spring,

he turns and, first taking some black beans,

averts his face and throws them; as he throws them, "I let these go"

he says; "with these beans, I redeem myself and mine."

He says this nine times and does not look back. The shade is thought

to gather the beans and follow behind, with no one looking.

The man again touches the water, and sounds the Temesan bronze,

and asks the shade to leave his house.

When he has said nine times "Ancestral spirits, leave,"

he looks back, and considers the rites to have been performed undefiled.Ovid, Fasti 5.421 ff.

For Thanksgiving, I reproduce the cover and three other pages from a delightful antique souvenir book, Souvenir of Dakota: The Artesian Wells, by Mrs. A.J. Dickinson, illustrated by Nelle B. Lockwood, both of Chamberlain, South Dakota, 1898. The text begins: On the dim silent prairie where brown grasses shiver, /And loneliness broods like a mystical spell, /There bursts on our vision a beautiful river, /Thrown up from the depths of a wonderful well. These words are illustrated by a wraithlike fountain spurting from the plain. The narrative includes such verses as Oh water, bright water, we see through thy prism /A vast panorama surpassingly grand: /We see the fulfillment of hopes and of wishes, /Good tidings of joy to this beautiful land. /We see through thy prism the gleaming and glancing /Of acres on acres of ripening wheat; /And we hear in thy music the songs of the reapers, /Who gather the food that the multitudes eat.

Photos by C.A. Sowa.

A quotation (from Horace) in honor of Columbus Day: on the courage of the sea voyager, October 2005 |

The perils of navigation

In October (traditionally on October 12, but now on the closest Monday), we celebrate the voyage of Columbus and the pride of the Italian people. While the journey, as with most historic events, was ambiguous in its results and meaning, and Columbus, of course, didn't "discover" the New World at all (it had already been discovered, and people were living in it), the skill and bravery of Columbus and his men and of all the early explorers, and of all who voyage upon the sea, is undeniable.

This month's quotation is translated from an ode by Horace dedicated to his friend the poet Vergil, who was about to embark on a trip to Greece. The distance between Greece and Italy seems short by today's standards, but storms can come up suddenly on the Mediterranean. Although one leaves port on a deceptively calm day, as I can attest from personal experience, one's small ship can be suddenly be tossed about by seemingly capricious gods. At such a time, passengers once prayed to Zeus or Jupiter; now they pray to the Virgin Mary.

(Explanation of names (some of which are Greek, although the poem itself is in Latin): African: the "south-west" wind; Aquilonian: the "north" wind; Hyades (Greek: "the Rainy Ones"): a cluster of stars in the constellation Taurus, thought to bring rain at the season of their morning setting (in November); Notus: the "south" wind; Acroceraunia (Greek: "Thunder Heights"): a rocky promontory in Epirus, Greece, jutting into the Ionian Sea.)

...

He was girt with oak and triple bronze

around his breast, who first entrusted his fragile ship

to the ferocious sea,

and did not fear the violent African winds

battling against the Aquilonian blasts,

nor feared the gloomy Hyades and the rage of Notus,

than whom there is no mightier arbiter of the Adriatic,

whether he wishes to raise or calm the straits.

What approach of Death did he fear,

who gazed with dry eyes upon the swimming monsters,

who saw the turbulent sea and

those infamous cliffs, Acroceraunia?

In vain did the foreseeing god cut off

the lands from each other by the dissociating Ocean,

if, nonetheless, impious ships

leap across depths that were never meant to be touched.

...Horace, Odes Book I, iii lines 9-24

A quotation suggested by Hurricane Katrina and the ruins of New Orleans and the Gulf Coast (from Juvenal's Satires), September 2005 |

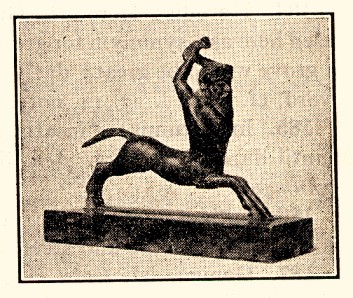

Codrus, the poor man who lost everything, owned a little statuette

of a centaur, like the bronze one pictured above.

In a disaster, the poor man is homeless while the rich man's friends rebuild his house

As we watched Hurricane Katrina and the breaking of the levees, and the subsequent agony of New Orleans and the Gulf coast, once again we saw how the poor are left to drown but the wealthy are enriched even beyond their previous lifestyle. President Bush gleefully described the opportunity afforded his crony, Mississippi Senator Trent Lott, by the destruction of (one of his) houses:

"Out of the rubble of Trent Lott's house - he's lost his entire house - there's going to be a fantastic house. And I'm looking forward to sitting on the porch."

A quotation springs to mind from the Roman satirist Juvenal (Decimus Junius Juvenalis, ca. 60-140 A.D.). In his Third Satire, Juvenal describes a chaotic urban world of fires, muggings, building collapses, and corrupt leaders that could just as well be today's news. In the excerpt translated below, the disaster is a pair of fires that consume a tenement and a mansion. The poor man, Codrus, loses "all the nothing that he owned," but the wealthy Persicus has rich friends who rush to rebuild his house. Persicus is represented as "childless," that is, without heirs, so his hangers-on hope to be named in his will. Just so, today's rich and powerful trade favors with each other.

...Codrus had a bed too short even for the dwarf Procula, and six little jugs,

the ornament of his sideboard. Under it was a small

drinking cup, and reclining beneath the same marble was [a statuette of the centaur] Chiron.

An elderly wicker chest contained some Greek booklets,

where barbarian mice gnawed at the divine poems.

Codrus had nothing. Who denies it? And yet,

poor man, he lost all of that nothing. But the final

climax of his misery is that, while he is naked and begging for scraps,

no one will help him with food, no one helps with hospitality or shelter.

But if the great mansion [built by] Asturicus has fallen, the matrons are dishevelled in mourning,

the nobles dress in black, and the magistrate postpones his court cases.

Then we groan over the accidents of the city, then we loathe the fire.

The blaze still rages, but already someone runs up to donate marble

and to contribute to the rebuilding fund. One man donates dazzling naked statues,

another a masterpiece by [the painter] Euphranor or [the sculptor] Polyclitus;

a lady contributes ancient ornaments plundered from the temples of Asian gods,

another man gives books and bookcases with a statue of Minerva in the middle,

another a bushel of silver. Persicus [the owner] replaces his loss with more and better things.

Most elegant of childless men, he is with good reason already

suspected of having set fire to his own house...Juvenal, Satire 3, lines 203-222

A quotation for the dog days of summer (from Hesiod's Works and Days), August 2005 |

In summer, women are sexy and men are weak

Sirius, the Dog Star, shines over the sweltering heat of summer, giving its name to the Dog Days of July and August. Hesiod (ca. 750 B.C.), the Old Curmudgeon of Greek epic poetry, thought the hot summer weather made women sexy and men weak. In his Works and Days, an excerpt of which appears below in translation, he recommends that a man enjoy his lunch and a jug of wine behind a shady rock, presumably to get away from those sex-crazed women.

When the artichoke blooms and the shrill cicada,

sitting in a tree, pours out its clear song

continually from beneath its wings, in the season of exhausting summer,

then the goats are fattest and the wine is best,

women are most sex-crazed and men are

weakest, because Sirius dries up the head and knees,

and the skin is dry from the heat. But at that time

let there be the shade of a rock and wine from Biblis,

and barley bread made with milk drained from goats

and meat of a heifer fed in the woods that has not yet calved,

and of firstborn kids. Drink the fiery wine, too,

while sitting in the shade, when you have satisfied your heart with food.

Then turning your face toward the strongly blowing Zephyr,

from an ever-flowing spring that runs mud-free,

pour three libations of water, but make a fourth libation of wine.Hesiod, Works and Days lines 582-596

A patriotic quotation (from Livy's Roman histories), July 2005 |

Cincinnatus called from the fields to become dictator of Rome

The Founding Fathers, Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, Franklin, et al. are our models for conducting our American Republic. The Founding Fathers, of course, not having themselves to look to as examples, turned to ancient Rome as their model. In particular, they were impressed by Cincinnatus, whom legend said was called from his farm to lead his nation in war, and who, after victory, returned to his simple life.

In the early days of the Roman Republic, Rome was still consolidating her power against the surrounding tribes. Among the most important rivals were the Sabines, the Aequi, and the Volsci. In about 460 B.C., a Roman force under the consul Lucius Minucius was cut off and surrounded by the Aequian enemy on Mount Algidus. Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a former consul, was called out of semi-retirement to assume the title of dictator and to lead a relief force. Under Cincinnatus' leadership, the Romans, in a short but decisive battle, rescued their brethern and defeated the Aequi. After the battle, Cincinnatus laid down his dictatorship and returned to private life.

The story of Cincinnatus was embroidered and expanded by the Roman annalists, so that it is sometimes difficult to disentangle fact from fiction (for example, he may or may not have held a second dictatorship). He is an ambiguous role model for American democracy for another reason: As a member of the patrician class, which held a stranglehold on wealth and power in Rome, he strongly opposed any measure that would extend power to the rising plebeian class!

George Washington, who was called out of retirement to become president, and, after serving two terms, retired again, was called an American Cincinnatus. The Society of the Cincinnati was founded by officers of the American Revolutionary army in 1783, and the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, was named for the Society of the Cincinnati. For the record, the original name of Cincinnati was also (semi-)classical; it was called Losantiville, for "town opposite the mouth of the Licking River!"

Below is the account of Cincinnatus (in Latin and English) as given in the Roman histories of Livy (59 B.C.-17 A.D.):

Livy's original (translation follows below)

...dictatoremque dici placeret qui rem perculsam restitueret, L. Quinctius Cincinnatus consensu omnium dicitur.Operae pretium est audire qui omnia prae divitiis humana spernunt neque honori magno locum neque virtuti putant esse, nisi ubi effuse afluant opes. Spes unica imperii populi Romani L. Quinctius trans Tiberim, contra eum ipsum locum ubi nunc navalia sunt, quattuor iugerum colebat agrum, quae prata Quinctia vocantur. Ibi ab legatis -- seu fossam fodiens palae innixus seu cum araret, operi certe, id quod constat, agresti intentus -- salute data in vicem redditaque rogatus ut, quod bene verteret ipsi reique publicae, togatus mandata senatus audiret, admiratus rogitansque "satin salve"?" togam propere e tugurio proferre uxorem Raciliam iubet. Qua simul absterso pulvere ac sudore velatus processit, dictatorem eum legati gratulantes consalutant, in urben vocant, qui terror sit in exercitu exponunt.

...

...Quinctius sexto decimo die dictatura in sex menses accepta se abdicavit.

(Livy, Book III.xxvi.6-10, xxix.7)

Translation

...a decision was made [by the Senate] to appoint a dictator to restore [Rome's] ruined fortunes, and Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus was named by universal consent.It is a story worth hearing, by anyone who spurns all human qualities except wealth, and who finds no place for great honor or virtue, unless riches flow copiously from it. The sole hope of the empire of the Roman people, Lucius Quinctius, was cultivating a field of four iugera [about three acres], on the other side of the Tiber, right across from the place where the dockyards now are. There -- whether he was digging a ditch as he leaned on his spade, or plowing, it is generally agreed that he was intent on some farm work -- he was greeted by the delegates and greeted them in return. They then asked him (and might it turn out well for himself and for the Republic!) to put on his toga and hear the mandate of the Senate. He, amazed, asked "Is all well," and bade his wife Racilia to quickly bring his toga from the cottage. When he had put it on, after wiping off the dust and sweat, he came forth, and the delegates, congratulating him and saluting him as dictator, explained the terrifying situation of the army...

[There follows an account of Cincinnatus' decisive battle and victory, as well as of the plebeians' misgivings at giving him so much power.]

...On the sixteenth day, Quinctius resigned from the dictatorship to which he had been appointed for six months.

A quotation (from Horace) for the start of vacation, June 2005 |

Vacation is a time to be silly

June brings the end of the school year. For some, this means graduation and the start of a first full-time job. For others, it brings summer school or a summer job. For many, it means a vacation, whether long or short, a respite from the tedium of winter. This month's quotation is a translation of the first and last verses of an ode by the Latin poet Horace (65-8 B.C.). It is addressed to a "Vergilius," who may have been Horace's famous contemporary, the poet Vergil. In it, he invites his friend to share a drink of wine and forget, if for a little while, the cares of life.

Zephyr breezes, companions of spring that calm the sea,

blow from Thrace to swell the sails;

the meadows are no longer frozen, nor do the rivers roar,

swollen with winter ice...

...Lay aside your objections and your eagerness to make money;

remember, while you can, how close are Death's dark fires,

and mingle your business plans with a little foolishness;

it is sweet to be silly on occasion.

Horace, Odes IV.12, lines 1-4, 25-28

Quotation (from Pindar) in honor of the Kentucky Derby, May 2005 |

Illustration: horse with frog jockey; this drawing and the one

below by Christine Cooper Angier, ca. 1980 (for Mother's Day, I offer

a couple of my Mom's animal pictures)

A winning horse at the Olympics

The ancient Olympic Games included not just track and field events, but also horse racing and chariot racing. (The modern Olympics, too, have some equestrian sports). Yet it is only a little exaggeration to call the Kentucky Derby (run this year on May 7) the true Olympics of horse racing. Then, as now, kings, princes, and wealthy aristocrats entered horses in the contest.

Pindar (518-438 B.C) composed victory odes for many Olympic winners in various events, as well as for the victors in other athletic festivals less well-remembered today -- the Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian games. The musical accompaniment to these odes is, of course, now lost, but we still have Pindar's glorious, ringing words. Here, in translation, are the opening lines of his Olympian Ode I, composed for King Hieron of Syracuse, whose horse Pherenikos ("Bringer of Victory") won the horse race in 476 B.C., as he was "speeding, unspurred" along the banks of the Alpheus River at Olympia (also called "Pisa" in this poem, for the surrounding district).

Water is the noblest element, and gold shines

like blazing fire in the night, beyond other lordly wealth.

But if you desire to sing

of games, o my heart,

do not look by day for any star more warmth-giving than the sun,

shining in the empty sky,

nor shall we proclaim another contest more excellent than Olympia...

...But now take the Dorian lyre down from its peg,

if the glory of Pisa and of Pherenikos

has placed your mind in the sweetest mood.

For he sped beside the river Alpheus,

yielding his great body to the race unspurred,

and brought to victorious power his master,

the chariot-fighting king of Syracuse...

Pindar, Olympian Ode I, lines 1-23

Quotation for Tax Preparation Season (Hesiod), April 2005 |

Wealth is best when won by healthy competition

April is tax month. Once again, our attention is called to the fact that while some people collect much ill-gotten wealth while doing little work, those who work the hardest often seem to gain the least. Our quotation of the month comes from Hesiod's Works and Days. Hesiod was approximately contemporary with Homer (ca. 750 B.C.), but his home, far removed from the heroic world of the Iliad and Odyssey, was the hardscrabble farmland of Ascra, in Boeotia. Hesiod addressed his homilies on farming and hard work and other folk wisdom to his ne'er-do-well brother Perses, who had cheated Hesiod by bribing the corrupt local lords to give him the larger share of their inheritance, then wasted his share.

Hesiod describes the Two Strifes. One kind of strife is bad, and leads to war. The other is good, and is the healthy competition that leads men to earn honest wealth.

Indeed, there was not just one kind of Strife, but upon the earth

there are two. A man would praise the one when he comes to know her;

the other is to be censured; for they differ in temper.

The one fosters evil war and battle,

-- cruel one! No mortal loves her, but by necessity,

through the will of the gods men pay honor to this grievous Strife.

But the other was first-born of dark Night,

and Zeus the son of Kronos, on his high throne, dwelling in the aether,

set her in the roots of the earth; she is much better for men.

She awakens even the shiftless man to work.

For a man desires to work when he sees another who is

rich, who is eager to plow and to plant,

and to put his house in order. And neighbor competes with neighbor,

hurrying after wealth. This is a good Strife for mortals.

And potter is jealous of potter, and craftsman of craftsman,

and beggar envies beggar and singer envies singer.

Hesiod,Works and Days lines 11-26

And again, Hesiod says,

If your heart within you desires wealth,

do these things, and work work upon work!

Hesiod,Works and Days lines 381-382

Quotations for the Spring Equinox (Vergil, Tibullus, Walter Pater), March, 2005 |

(Illustration: decoration from Longus, Daphnis and Chloe: A Pastoral Romance, English translation, 19th cent.; engraving of 1763.)

In primis venerare deos, atque annua magnae

sacra refer Cereri laetis operatus in herbis

extremae sub casum hiemis, iam vere sereno.

(In particular, venerate the gods, and offer the yearly sacrifice

to great Ceres, performing her rites in the flourishing grass,

at the very end of winter, in the fair spring.)

Vergil, Georgic I, vv. 338-340, tr. C.A. Sowa.

Animals and fertility in spring celebrations

This is the time of Easter, of the first day of spring--the Vernal Equinox--and of St. Patrick's Day. Pale Male and Lola, the red-tailed hawks whose acrobatics have for several years enchanted New Yorkers, once again are caring for eggs in their nest on a twelfth-floor cornice high above Fifth Avenue, across from Central Park. Pale Male, always the gentleman, brings offerings of pigeons to his lady-love. The exuberant limestone acanthus carvings surrounding the birds' home echoes the arrival of greenery and new life.

In ancient Roman times, this was the season of the rustic celebration of the Ambarvalia, when animals to be sacrificed were led around the boundaries of each farm, to ensure the fertility of the fields. This is the ritual referred to by Vergil in the quotation from the First Georgic quoted above.

Walter Pater, Victorian essayist and critic, wrote his novel Marius the Epicurean as a fictional recreation of the life of a young Roman. At the beginning of the novel, Marius is celebrating the Ambarvalia on his ancestral estate (by the end of the novel, however, he has become a Christian). In the first chapter, Pater, quoting Tibullus (ca. 55-19 B.C). evokes the mystery of a natural world alive with inhabiting spirits. (The translation from Tibullus is mine; Pater gave only the Latin.)

"[T]he religion of Numa," as people loved to fancy, lingered on with little change amid the pastoral life... Glimpses of such a survival we may catch below the merely artificial attitudes of Latin pastoral poetry; in Tibullus especially, who has preserved for us many poetic details of old Roman religious usage.

At mihi contingat patrios celebrare Penates,

Reddereque antiquo menstrua thura Lari:

[May it be my lot to honor the ancestral household spirits

And to offer, each month, incense to the ancient domestic god.]...A religion of usages and sentiment rather than of facts and belief, and attached to very definite things and places--the oak of immemorial age, the rock on the heath fashioned by weather as if by some dim human art, the shadowy grove of ilex, passing into which one exclaimed involuntarily, in consecrated phrase, Deity is in this Place! Numen Inest!--it was in natural harmony with the temper of a quiet people amid the spectacle of rural life, like that simpler faith between man and man, which Tibullus expressly connects with the period when, with an inexpensive worship, the old wooden gods had been still pressed for room in their homely little shrines.

The quotation from Tibullus is from Book I, No. 3, ll.33-34; Pater could well have quoted another of Tibullus' elegies, Book II, No. 1, an actual (poetic) description of the Ambarvalia.

Quotation for Valentine's Day (Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite), February, 2005 |

(Illustration: a chapter headpiece for Longus, Daphnis and Chloe: A Pastoral Romance, English translation, 19th cent., engraving after a design by the Regent, Philippe d'Orléans for an edition of 1718.)

SEX AND THE MOUNTAIN: Aphrodite, goddess of sexual desire and fertility, hastening to seduce Anchises on Mount Ida, causes the wild forest animals to mate as she passes them

In the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite (a poem dating from perhaps shortly after Homer himself), Aphrodite, the "golden goddess" (polychrusos) makes everyone, including gods, mortals, and all the creatures of the land and sea, fall in love. Only the goddesses Athena, Artemis, and Hestia are immune to her snares. Even Zeus, king of the gods, has been led astray by her many times. But Aphrodite herself has never been in love. Zeus takes revenge by making her fall in love with the Trojan prince Anchises, whom she seduces as he tends cattle on a mountain top. Shamed by loss of the power which she had wielded by remaining above the fray, she nevertheless becomes the mother of a mighty son, the hero Aeneas. He, in turn, was to become even more famous in Roman times, as the founder of Rome in Vergil's Aeneid.

[Zeus] put sweet desire for Anchises in her heart;

Anchises was, at the time, on the steep mountain slopes of many-fountained Ida

tending cattle, looking, in build and stature, like the immortal gods.

When laughter-loving Aphrodite saw him,

she fell in love, and a terrible desire seized her senses.

Going to Cyprus, she entered her incense-fragrant temple

in Paphos, where she has a sacred precinct and a fragrant altar.

Going in, she closed the shining doors;

there, the Graces bathed her and anointed her with heavenly oil,

such as lies upon the bodies of the immortal gods,

ambrosial and sweet, which she had by her.

Clothing herself entirely in beautiful garments

and ornamented in gold, laughter-loving Aphrodite

rushed to Troy, leaving fragrant Cyprus,

quickly making her journey high among the clouds.

She came to many-fountained Ida, mother of wild beasts,

and went straight across the mountain to the farmstead.

After her came gray wolves, fawning upon her, and flashing-eyed lions,

bears, and swift leopards ravenous for deer.

She, seeing them, was happy in her heart,

and put desire in their breasts; at the same time

they all started mating, two by two, in their shady abodes.

(-Homeric Hymn V to Aphrodite, vv. 53-74, tr. C.A. Sowa)

Quotations for the Winter Solstice (Catullus and Hesiod), December-January, 2004-5 |

Winter is for celebrating -- and for doing indoor work!

The Saturnalia, the ancient festival of Saturn, was celebrated in Rome on December 17. Presents were exchanged, slaves were treated as equals of their masters, and freedom and jollity prevailed.

Saturnalibus, optimo dierum!

On the Saturnalia, best of days!

(-Catullus 14.15)

Another, more wintry view (in attitude as well as season) of this time of year is presented by the Boeotian Hesiod, who cautions the good farmer to use the indoor time well in taking care of household matters.

Pass by the seat at the bronze-smith's forge and the warm lodging-house

in winter, when the cold keeps a man from work --

for then the resolute man can be of great help to his household --

lest the hardship of winter overtake you, along with poverty,

and you massage a swollen foot with a shrunken hand.

Many are the mischievous thoughts that occur to the idle man,

who waits for a vain hope, lacking a means of livelihood.

....

Avoid the month of Lenaion [December-January] -- evil days,

all of them fit to flay an ox! -- and the frosts which arise, painful,

upon the earth when Boreas the North Wind blows;

who, blowing through horse-breeding Thrace upon the wide sea,

makes it heave, and the earth and the woods howl;

falling upon many high-crowned oaks and thick pines

in the mountain glens, Boreas brings them to the bounteous ground;

then the entire immense wood roars,

and the wild beasts shudder and put their tails between their legs,

even those whose hide is covered with fur;

chill as he is, he blows through them, although they are shaggy-breasted.

....

(-Hesiod,Works and Days, vv. 493-514)

---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2004 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: