These are quotations for the year 2009. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2009, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2009 |

Below are quotations for the year 2009. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2009

Click on a link to read each quotation

2009

- December 2009: In the winter season of the Northern Hemisphere, a shout-out to the Antipodes, where it's summer. The Antipodes as a real place in Plato, as a state of mind in Seneca's satire of modern overindulgence.

- November 2009: Inspired by the debate over health care, "A cock for Asclepius" (from Plato's Phaedo).

- October 2009: For Halloween, Odysseus summons the ghosts of the dead (Odyssey Book 11).

- September 2009: For the beginning of the school year, quotations from Plato and Cicero on the need for a broad education.

- August 2009: Inspired by the 40th anniversary of the Woodstock Festival, quotations from Plato on the elevating or corrupting influence of music in education.

- July 2009: In honor of the astronauts' moon landing, we have quotations from the Homeric Hymns and Apollonius Rhodius' Argonautica, on the moon as goddess and as object of witchcraft.

- June 2009: Inspired by the nomination of Judge Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court, we cite Athena's judgment in favor of Orestes in Aeschylus' Eumenides

- May 2009: Inspired by the current hysteria about "swine flu," we quote Pindar's impassioned defense against the slur "Boeotian pig."

- April 2009: Ovid, in the Fasti, wonders about the name of the month of April; why is it not named for Venus? (Perhaps it is named for Aphrodite, the Greek counterpart of Venus?)

- March 2009: As we are reminded by the task of cleaning up the world's crises, Heracles had to clean up the Augeian stables, whose vastness is described by Theocritus.

- February 2009: For the financial meltdown and other follies, wisdom from a Cretan knife ("Don't take a trip with your mind unless you see a road...").

- January 2009: For the inauguration of President Barack Obama, Vergil's prediction of a new Golden Age in his Fourth Eclogue.

Quotation for December 2009: In the winter season of the Northern Hemisphere, a shout-out to the Antipodes, where it's summer |

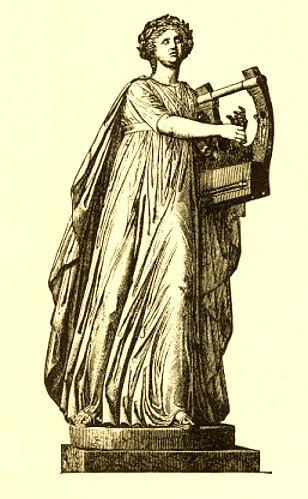

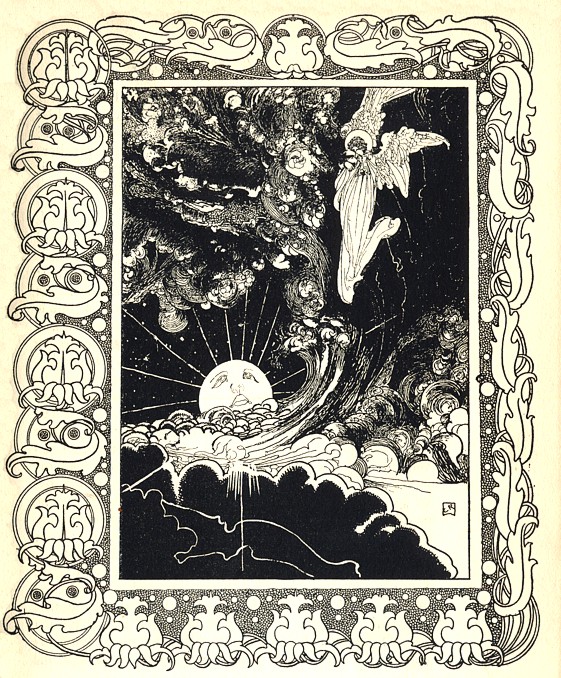

Helios, god of the Sun, pilots his chariot across the sky. Metope from the Temple of Athena, Troy VIII (after 390 B.C.), now in Berlin, Altes Museum. (Image from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.) For those who sleep by day and party by night, this is a sight never seen.

Winter here, summer there

In the Northern Hemisphere, from which this Web site originates, this is the beginning of winter. The days grow shorter, and the U.S. has suffered its first blizzards, shutting down highways, trapping hikers, and bringing down power lines. The wind howls through the trees. As Hesiod says, it is then that Boreas, the North Wind,

blowing through horse-breeding Thrace upon the wide sea, |

In our modern world, in the face of the blast, Christmas and Hanukkah lights, swaying in the wind, spread cheer.

For an even bigger contrast, we are mindful of our readers in the Southern Hemisphere, our Antipodes, for whom this is the beginning of summer, as the days grow longer.

The Antipodes as an actual place (in Plato's Timaeus)

It was known since Pythagoras that the Earth was a globe. It is simply not true that people thought the Earth was flat until Columbus proved it otherwise. (That particular canard was started by a work of fiction, Washington Irving's The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus (1828), and continued by the dubious work of the anti-religious writer Antoine-Jean Letronne in his On the Cosmographical Ideas of the Church Fathers (1834).)

Plato, as he describes it in the Timaeus, conceived of the universe as spherical, with the Earth at its center (and as having a soul). In the Timaeus (more famous today for its myth of Atlantis), he invokes the concept of the Antipodes to explain why there is no actual "up" or "down," since upness and downness depends on where you are standing. "Antipodes" literally means "with opposite feet (to where you are standing)." He is explaining that things are light or heavy not because they fall down but because elements (earth, air, water, fire) are attracted to similar elements, the elements themselves being composed of atoms shaped like different kinds of triangles (Timaeus 63a).

In the Phaedo, Plato described the Earth itself as spherical, resembling, he says, a ball made of different colored strips of leather (Phaedo 110b).

The Antipodes as a state of mind (in Seneca's Epistles)

Seneca the Younger (1st cent. A.D.), in his ironic Epistles, turns the idea of the Antipodes on its head, so to speak, using the term humorously to describe the state of mind of those who pervert the normal scheme of things. He mocks lazy souls who sleep by day and banquet by night (whose minds, he says, are as full of darkness and fog as their lives), gourmands who cultivate flowers out of season or grow orchards on their roofs, and men who wear women's clothes.

Here is the beginning of Seneca's Epistle 122, written as the days grow shorter. The quotation from Vergil is from Georgic 1.250-1, where the context shows that the poet assumes that the Sun, moving around the Earth, alternately illuminates the northern and southern hemispheres. The reference to Cato is not recorded elsewhere.

The day already feels its loss. It has retreated somewhat, yet there is still a generous amount, if one arises, so to speak, with the day itself. One is even more industrious, and better off, if one does not wait for the first light, but wakes it up. He is shameful, who, when the sun is high, lies semi-asleep, and whose watchful time begins in mid-day; and yet for many, this is before their dawn. There are those who reverse the duties of day and night, and do not open their eyes, heavy with yesterday's drunkenness, until night begins to approach. Such is said to be the condition of those whom nature, as Vergil says, has placed contrary to our dwelling place,"and when the Rising Sun with his panting horses has breathed upon usBut for these people, what is contrary is not their region, but their life. There are in this same city certain antipodes, who, as Cato says, never see either the rising or the setting sun. Do you think they know how to live, who do not even know when to live? And that they fear death, who have buried themselves alive? They are of evil omen, like nocturnal birds... |

"Galileo Demonstrating His System," from Burritt's Geography of the Heavens, New York, 1856.

Quotation for November 2009: Inspired by the debate over health care, "A cock for Asclepius" |

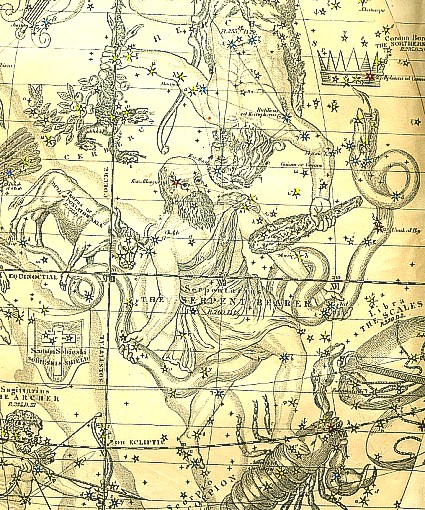

The constellation Ophiuchus ("The Serpent Bearer"), sometimes identified with the god Asclepius. (Detail from Burritt's Geography of the Heavens, 1856.)

An ancient New Age spa

Imagine a New Age spa, where, after the proper rituals and having bathed in medicinal waters, you go to sleep in a temple inhabited by sacred animals, and dreams direct your cure of all that troubles you.

This month, inspired by the debate in Congress and the media over what kind of health care is best for the nation (and how to pay for it), we discuss the cult of Asclepius (Roman Aesculapius), the ancient god of medicine, whose temples and sacred precincts were popular resorts for the sick, the infirm, and the worried.

Healing dreams in the temple of Asclepius

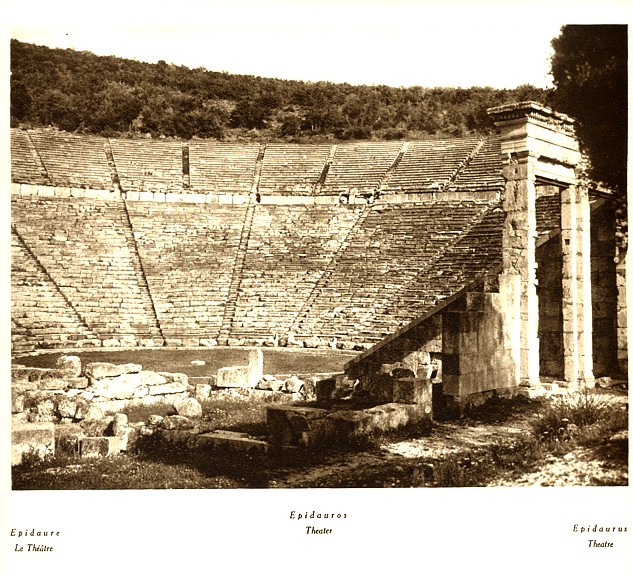

In Homer, Asclepius is apparently simply another hero, a physician, father of the two doctors Machaon and Podalirius. He was taught his craft by the centaur Chiron. As discussed in Farnell Greek Hero Cults, there is a question of whether Asclepius was a person whom the tradition gradually made into a god, or whether he started as a god who became a hero. He is sometimes portrayed as the son of Apollo. He is associated with snakes (as symbols of rejuvenation because of the way the slough off their skins) and with dogs. One tradition has him transformed into the constellation Ophiuchus, the "Snake-Holder" (see the picture above). By historic times, the cult of physicians called the Asclepiades or "sons of Asclepius" had grown around him (of whom the most famous was Hippocrates of Cos), and his shrines, in which there were often resident snakes (and sometimes sacred dogs), were places of healing. The most famous rites associated with these shrines was the practice of "incubation" or sleeping overnight in the temple, where dreams would dictate the course of treatment. Many cures were reported: sterile women became pregnant, the depressed found their spirits again. At the largest sacred sites, as at Epidaurus (south of Athens), the island of Cos, and Pergamum (in Asia Minor), there were temples, baths, gymnasia, theaters, and other buildings. At Epidaurus, the large theater is still used for performances (see the illustration below).

Asclepius is portrayed holding a staff and a snake, often with the snake wrapped around the staff. The staff with the single snake is used as the symbol for a number of medical associations. (Other medical groups use the alternative staff with two snakes, topped with wings, called the caduceus (Greek kerykion) or herald's staff, associated with Hermes, the Roman Mercury. Hermes' "snakes," however, developed artistically from images of twining shoots of foliage.)

Socrates' "cock for Asclepius"

The most famous (and enigmatic) reference to Asclepius is in Plato's Phaedo, which describes the last day of Socrates, condemned to drink the poison hemlock for "corrupting the youth of Athens" with his weird ideas. Socrates spends the day in his prison cell conversing with his friends, discussing the nature of the soul, reasons against suicide, arguments for reincarnation, and attitudes toward mortality, trying to console the young men for his impending death. By the end of the day, all but Socrates are crying, even the jailer whose duty is to give him the poison, who apologizes profusely for what he is ordered to do. (Socrates, in fact, had practically demanded his own martyrdom, being given a chance to ask for a lesser sentence but refusing to. When asked what punishment he should be given, he answered that he should actually be rewarded, as were Olympic victors, with dining privileges in the prytaneon (town hall)! Fat chance!) Socrates reprimands the men for their behavior — he had sent his wife and other women out of the room precisely because of their womanish crying.

As he dies, Socrates' last words are a request that Crito offer "a cock to Asclepius" which he says he owes. This reference has left commentators scratching their heads for centuries. One interpretation is that the offering is in gratitude for release of his immortal soul from his mortal body. I suggest a more mundane explanation: Socrates has been trying to cheer up his followers by acting as if the whole activity were a perfectly normal medical procedure. Perhaps his request is simply to be interpreted as "Hey, Crito, remember to pay the doctor after this is over." Or maybe (assuming that the Phaedo is a more or less actual report of what happened that day) Socrates actually did remember that he owed a sacrifice to the god for some prior favor. Or, as the poison crept up his body, was his mind just starting to wander? Here, in translation is the ending of the Phaedo:

. . . Apollodorus, who even before this had not ceased weeping, now crying out in bellowing tears and grieving made everyone present break down except Socrates. |

Statue of Asclepius, Louvre. The god is holding his staff and is accompanied by a snake. The snake is often depicted as twined around the staff. The staff with (single) twined snake is used as the symbol of a number of medical associations. (Image from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

The theater at Epidaurus. (From Hanns Holdt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Griechenland, 3rd edition, 1928.) Only the theater still stands of the huge sanitorium and spa complex once dedicated to Asclepius.

Quotation for October 2009: For Halloween, Odysseus summons the ghosts of the dead |

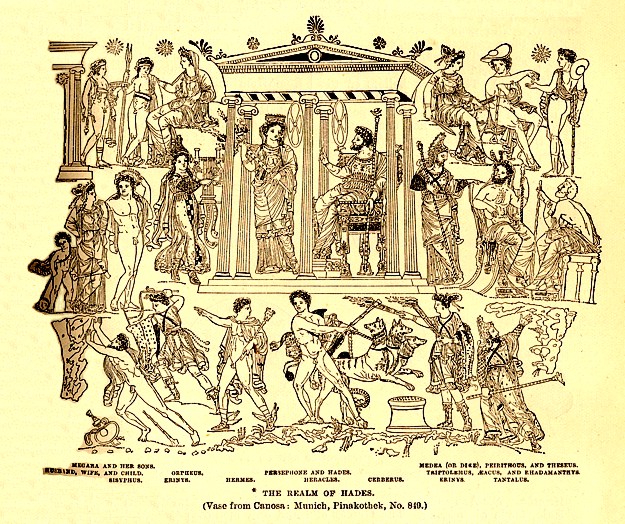

The realm of Hades. (Adapted from the image of a vase from Canosa in Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.) Hades and Persephone appear in the shrine at the top. Notice Heracles kidnapping the three-headed dog Cerberus at the bottom center and Sisyphus pushing his rock up a hill at the bottom left.

Odysseus in the realm of the dead

Perhaps the most extraordinary ghost story of antiquity is Book 11 of the Odyssey, in which Odysseus visits the Land of the Dead. There, he exchanges gossip with lost loved ones, learns the fate of his fellow warriors, meets phantoms of the past, and hears of the future that is in store for him.

Circe, sorceress of Aeaea ("Island of Wails"), who earlier turned Odysseus' men to swine, after a year lets Odysseus and crew leave, but first she tells him he must journey across the Ocean, the great river encircling the world, to the entrance to the home of Hades and Persephone. There he must dig a trench and make sacrifices, but he must not let the phantom dead who throng about him drink the blood (which allows them to communicate) until he has inquired of the soul (psyche) of the great Theban seer Teiresias what his own future holds, for

. . . his mental faculties (phrenes) are intact, for to him alone, though dead, has Persephone granted reason (nóon), |

A ghostly stampede around the blood-filled trench

In a shadowy land, where the sun does not shine, Odysseus, following Circe's instructions, stands at the blood-filled trench as the phantoms come, from all walks of life, crying out: brides and youths and worn-out old men, warriors in blood-stained armor, dead young girls "with their hearts new to sorrow." Odysseus feels a pang as he turns away his own mother, Anticleia, whom he last saw alive when he departed for Troy. But he can allow no one to drink the blood before he has inquired of Teiresias, the seer. Teiresias' prophecy being done, he at last lets his mother drink the blood and receives her news from home, but as he tries to embrace her, "she flits away, like a shadow or a dream." He meets famous women, including the mother of Oedipus (here called Epicaste rather than the usual Iocaste or "Jocasta"). He converses with Agamemnon, murdered by his wife, Clytaemnestra, who warns Odysseus not to trust his own wife, though admitting that Penelope is a good woman. He meets Heracles, who is chasing wild game, but it is only his "likeness" (eidolon), for "he himself" enjoys himself among the immortal gods, having Hebe for a wife. He sees the great sinners (as Dante would later do): Tantalus forever grasping at fruit overhead and thirsting for water receding around him, and Sisyphus endlessly rolling his stone uphill.

Achilles: "Better to be a serf on earth than king of all the dead"

Upon meeting the ghost of Achilles, who weeps at seeing him in this nightmare land, Odysseus attempts to cheer him up, contrasting Achilles' heroic fate with his own endless wanderings, but Achilles would rather be a peasant — and be alive. He is happy only when Odysseus tells him that his son, Neoptolemus, lives and is successful in battle. Ajax, on the other hand, still smarting from his loss to Odysseus in the contest for the arms of Achilles, refuses to speak to him. At last, besieged by crowds of ghosts, Odysseus leaves, afraid that Persephone will send up the monster head of the Gorgon.

Here is part of the conversation with Achilles, who asks what Odysseus is doing in Hades' kingdom:

Thus he spoke, and I addressed him in answer, |

Among the ghosts encountered by Odysseus in the Land of the Dead was that of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, leader of the Greeks in the Trojan War. The Lion Gate that we see today at Mycenae dates from a later time, replacing the one from which Agamemnon would have departed for the war, and through which he returned, only to be murdered by his wife Clytaemnestra. (Illustration: The Lion Gate at Mycenae, from Chrestos Tsountas and J. Irving Manatt, The Mycenaean Age, 1897, from a photograph by Professor Colwell.)

Quotation for September 2009: For the beginning of the school year, quotations from Plato and Cicero on education |

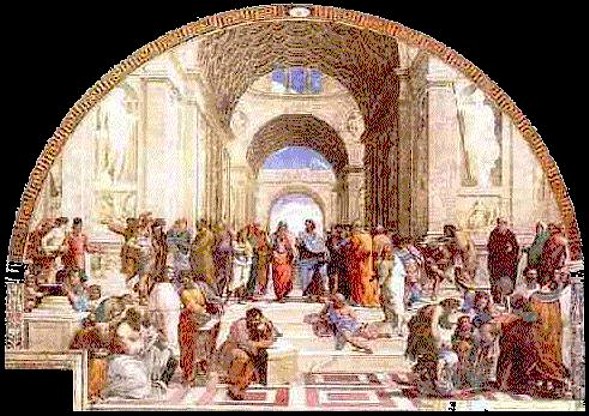

Raphael, fresco "The School of Athens," in the Stanza della Segnatura, the Vatican (1508-1511). Plato and Aristotle are at the center of the fresco, with Plato pointing toward heaven and the world of Forms, Aristotle pointing toward earth and the world of Things.

The need for a wide education

More than one observer of the academic world has bemoaned the fact that universities, especially graduate schools, have become more and more like trade schools, training students for a narrow proficiency in some skill at which they hope they can get a job. The aim seems to be lost of encouraging students to become well-educated, thoughtful citizens who can think critically about the world around them (and might, incidentally, be better able to change careers when necessary).

Mark Taylor, chairman of the religion department at Columbia University, in an op-ed piece in the New York Times, later quoted in the "College Pump" page of Harvard Magazine for July-August 2009, described graduate education as "the Detroit of higher learning," writing

"Most graduate programs in American universities produce a product for which there is no market (candidates for teaching positions that do not exist) and develop skills for which there is diminishing demand (research in subfields within subfields and publication in journals read by no one other than a few like-minded colleagues), all at a rapidly rising cost (sometimes well over $100,000 in student loans)."

We are reminded of the old joke, "A specialist is someone who learns more and more about less and less until he knows everything about nothing."

Obviously, it is the premise of this page that a knowledge of Classical literature, in all its many subjects, gives us insight into our world today.

Plato and Cicero on career training

Our quotations this month are from Plato and Cicero, the Greek philosopher and the Roman politician, different in many ways, but both seeing the need for a broad education for anyone in training to be a public leader.

Plato, in his Republic (Politeia), laid out an entire curriculum for his Guardians (phylakes), warrior philosophers who were to protect and lead his ideal city-state, both men and women (for he thought that men and women should receive the same education, although he believed that women could never be as capable as men). Plato planned the course of study in excruciating detail. Some of his thoughts and prejudices about music were quoted in the Quotation of the Month for August (stay away from those flutes; they make you soft!). He would begin in youth with music, in which he included literature (which was only to include edifying subjects, not portraying un-guardian-like behavior), then proceed to gynmastics. Later, they would study mathematics and astronomy, which are useful to the soldier in the field, but, more importantly, provide a pattern for understanding the true absolutes that are known not by the senses but by reason alone. In Book 7, he introduces the allegory of the cave, where prisoners know reality only by shadows cast by a fire behind them on a wall before them. They see true reality, illuminated by the real sun, only when they are released from the cave. The well-educated guardians, released from their "cave" of the ordinary world of the senses, see true reality by the light of reason, but must descend back into the cave to lead those who still remain prisoners. The final stage of education for the guardians is in dialectic (dialegesthai "to dialog, discuss, argue"), through which one arrives by logic (logos) and intellect (noêsis) at absolute knowledge, and finally knowledge of absolute good. It is from this culminating stage of education that we quote below.

Cicero's de Oratore (55.B.C.) is much more practical, coming from a writer who was both trial lawyer and politician. He makes the interesting point that a wide education actually makes one better at what seems to be a narrow profession of oratory. The De Oratore is presented as a dialog, supposedly taking place in 91 B.C., between Cicero's predecessor and mentor Crassus (who is Cicero's mouthpiece in the dialog) and several other eminent Romans. Cicero, in his introduction, presents the work as an answer to his brother Quintus, who apparently believed that talent and practical experience were all that was necessary to make either a good lawyer or a good speaker in the Senate. His is the view represented by Crassus' interlocutors in the dialog. Cicero's arguments for a wide education are not utopian, like Plato's, but based on usefulness. In presenting legal arguments, the lawyer must be familiar with all the topics that may come up; the same is true of speaking in the Senate. Beyond that, education (or lack of it) will show, no matter what the topic. In the De Oratore, Cicero covers many techniques (including humor and emotion) that can be used by the orator, and includes a discussion of the uses of Stoic and other philosophy in the pursuit of oratory. From this wide-ranging treatise, we quote some of the dialog ascribed to Crassus on the need for a broad-based training in oratory, which he compares to education in sports and painting.

|

|

Quotation for August 2009: Inspired by the 40th anniversary of the Woodstock Festival, we quote some conservative criticism of the elevating or corrupting influence of music from Plato's Republic and Laws |

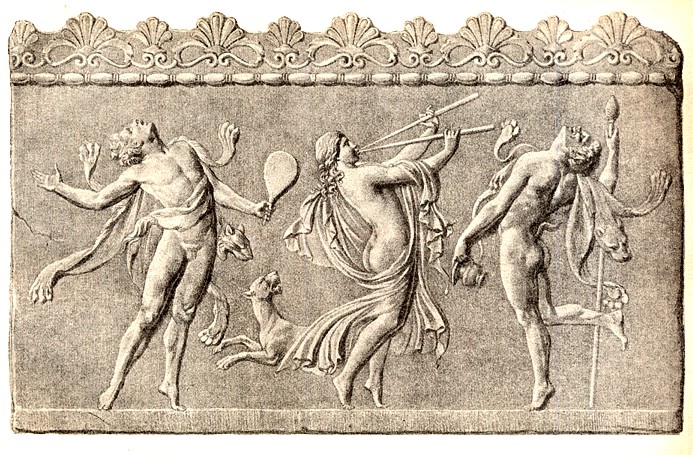

Party on! A Maenad (a "Crazy") plays the flute in a Dionysiac festival.

Woodstock and Plato

August 2009 marked the 40th anniversary of the Woodstock Music Festival. Sex, drugs, rock and roll! Woodstock has become a symbol for everything denoted by the term "The Sixties." It was a time of societal upheaval and rebellion, against targets real (Jim Crow segregation, second-class status of women) and perceived (conventional clothes, bland music, conformity in general). Much of the rebellion coalesced around protesting against the war in Vietnam, still a subject of argument today. There were assassinations (John Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, John Lennon), riots, bombings, and bad acid trips. But many good things came out of the period, too, the civil rights movement, women's liberation, the environmental movement. The psychedelic art was imaginative and colorful. In July of 1969, men walked on the moon —but no women, who weren't allowed to be astronauts. It was a liberating time for many, but disorienting and frightening for those who felt safe within the conformity and conservatism of an earlier period. Now we have an African-American president, Barack Obama, and a Puerto Rican woman, Sonia Sotomayor, on the Supreme Court, and again there are those who feel anxiety at an unfamiliar world.

And then there was the music! It was loud, all electric guitars and drums, voices that screamed and incited to licentious behavior!. The men had long hair and the women had no bras. And it sounded best when you were stoned. Today, rock and roll is mainstream, and there is a Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Very bourgeois.

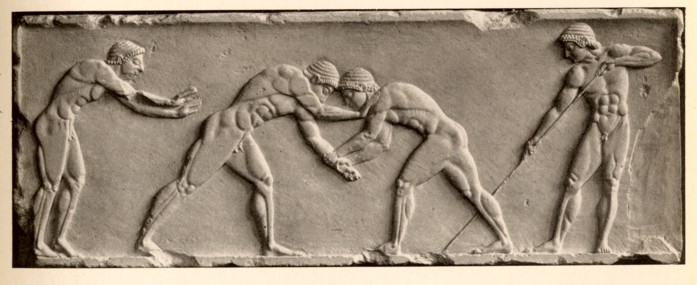

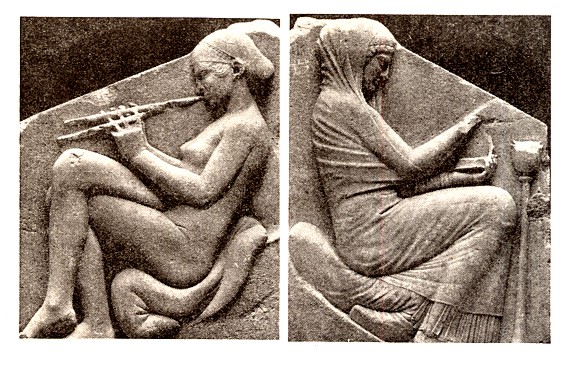

The Republic and Laws: micromanaging music

In Classical Greece, Plato gave voice to the same concern over the power of music to promote certain kinds of behavior. In both the Republic and the Laws he attempts to micromanage the notes, rhythms, words, and instruments that are to be used in the education of his perfect citizen. We quote below excerpts from both works.

In the Republic, he dismisses the Lydian and Ionian modes, as promoting indolence and softness, but recommends the Dorian and Phrygian modes, as becoming the stern soldier in war and peace, respectively. The worst kind of music is that played on the flute. The flute was considered suitable only for satyrs, prostitutes, and the Maenads ("crazy women," from mainomai, to rage, be mad) who followed after Dionysus in his bacchanals.

In the Laws, a character called The Athenian inveighs against the mixing up of various kinds of music which should be kept separate (hymns, paeans, dithyrambs, etc.). People actually think they can decide for themselves what they think sounds good!

|

|

Bad girl/good girl. "The courtesan and the modest wife," reliefs on the sides of the Ludovisi Throne, Terme Museum, Rome.

Quotation for July 2009: In honor of the astronauts' moon landing, quotations from the Homeric Hymns and Apollonius Rhodius' Argonautica, on the moon as goddess and as object of witchcraft. |

The moon, in an illustration by Charles Robinson for "What the Moon Saw," by Hans Christian Andersen, in Fairy Tales, translated by Mrs. E. Lucas, 1903.

A voyage to the moon

Forty years ago, two American astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, walked on the moon. Since an initial flurry of return trips, no one has journeyed there, and the exploit has receded into the mists of time, and like the historic events of the Trojan War, become a myth. Even at the time, the elements of the heroic Journey theme (as identified in my book Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns) were acted out. As I further pointed out in Ancient Myths in Modern Movies, the astronauts left on the moon a statuette of the Fallen Astronaut, commemorating the astronauts and cosmonauts who died during the space program. It is a representation of the Death of the Substitute, a necessary element of every Journey myth. No one can come back from the Land of the Dead without some loss.

A personal note: I watched the moon landing on a giant screen while sitting with a large crowd on the floor of the Student Union at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, a magic moment. I was attending a six-week Summer Institute on Computers and Classics, an intensive workshop that was seminal for many of us in the field of digital humanities. Now there's another event that should be repeated!

The moon as goddess or as object of witchcraft

In antiquity, no one thought of the Moon as a place to go. Selene, the Moon, and Helios, the Sun, were divinities that drove great teams of horses as they "plowed deep furrows" across the sky. There was no specific cult of Selene among the Greeks (there was, though, a Roman cult of Luna). She was, however, identified with several other goddesses, including Artemis, Eos ("Dawn"), Hecate, and Persephone (the last two being goddesses associated with the Underworld). In the Homeric Hymn to Selene (quoted below) she is described as having wings, an attribute belonging to Eos. The moon was important in sorcery and witchcraft. In Theocritus' Idyll II (which we excerpted in the quotation for July, 2007), the (rather amateurish) witch, attempting to use magic to win back a boyfriend who dumped her, invokes Selene in the refrain "Tell me whence my love came, Lady Selene" (phrazeo meu ton erôth' hothen hiketo, potna Selana). Witches were supposed to be able to draw down the moon, as well as to stop rivers in their course.

This month, we have two quotations. The first is the complete Homeric Hymn XXII to Selene (7th cent. B.C.?). This is one of the short Hymns, which does not tell a long story (like the Hymns to Demeter, Apollo, Demeter, and Apollo), but was perhaps used as an introductory song for a longer piece. The second is a description of one of the world's most famous sorceresses, Medea, from the Argonautica of the Alexandrian poet Apollonius Rhodius (3rd cent. B.C.). Medea, in the well-known story, helped Jason and the Argonauts in their quest for the Golden Fleece; he then married her, and took her home with him. There were many versions, but the one best known to modern playgoers and readers is the one told in Euripides' Medea, in which she kills her own children as revenge against Jason, who abandoned her for another woman, and this is where the modern emphasis lies. But in Hesiod's Theogony, there is no "Other Woman" and no infanticide; Jason and the "daughter of Aeetes" (her actual name not given) have a son Medeus, who is reared by the centaur Chiron, who also tutored both Jason and Achilles. In most versions, she is a witch, possibly a goddess. She renewed the youth of Jason's father, Aeson, by boiling him in herbs (then pretended to do the same for Pelias, but really killed him). We quote below the lines from the Argonautica in which Argos (builder of the ship Argo, in which the Argonauts sailed, and nephew of Medea), describes Medea, whom he thinks will be helpful to Jason. She is depicted with the stereotypical qualities of a well-equipped witch.

The Homeric Hymn to Selene:

Sing of the long-winged Moon, and tell me of her, Muses, |

Excerpt from Apollonius Rhodius' Argonautica:

. . . |

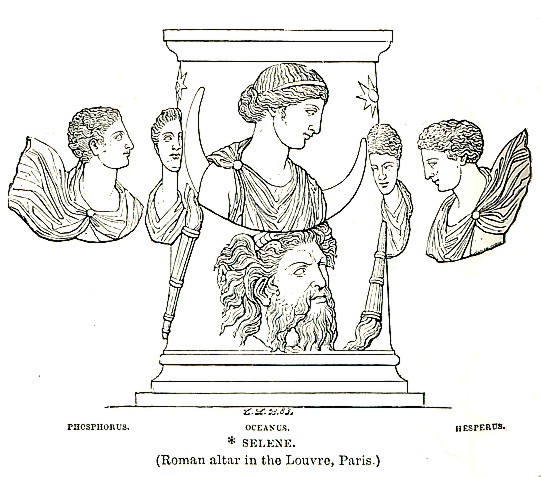

Selene, on a Roman altar in the Louvre, from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.

Quotation for June 2009: Inspired by the nomination of Judge Sonia Sotomayor to the Supreme Court, we cite Athena's judgment in favor of Orestes in Aeschylus' Eumenides |

The judgment of a wise woman

The abundantly well-qualified Judge Sonia Sotomayor, nominated by President Barack Obama to the U.S. Supreme Court, has left her conservative opponents scrambling for some flaw in her character. Judge Sotomayor would not only be one of a minuscule number of women to have served on the Court, she would be its first Latino (or Latina) member. Her foes have fastened on a remark of hers that they claim proves her lack of impartiality and hence unfitness for the position, in which she famously said,

"I would hope that a wise Latina woman with the richness of her experiences would more often than not reach a better conclusion than a white male who hasnít lived that life."

Of course, if our life experiences were not brought to bear on all our actions and decisions, there would be little purpose in having any experience at all. Funny that no one ever thought that white male judges might not be influenced by some of their own backgrounds and life's journeys. Come to think of it, if we want a strict, mechanical, robotic interpretation of the law, which would be the same no matter who the judges were, why do we need nine redundant judges in the first place? Actually, Judge Sotomayor's judicial decisions in the lower courts have been quite centrist and non-ideological, not as her opponents would have us believe.

Athena and the Areopagus

We are reminded of the most famous female judge of all, the goddess Athena, as depicted in Aeschylus Eumenides, in which she finds Orestes not guilty in the murder of his mother, Clytaemnestra. Athena, too, did not decide the case in the way that might have been predicted.

In the first two plays of Aeschylus' Oresteia trilogy, the Agamemnon and the Choephoroi (Libation Bearers), Orestes has killed his mother Clytaemnestra in retribution for her murder of his father Agamemnon on his return from the Trojan War. For this matricide, Orestes is pursued by the Furies (Erinyes). In the final play, the Eumenides (Kindly Goddesses), Orestes is told by Apollo's oracle at Delphi to seek justice in Athens. Athena herself undertakes the case, but chooses a jury of wise Athenian citizens, the Council of the Areopagus ("Ares' Hill"), to help her judge Orestes' guilt or innocence, in the very first trial for homicide. Athena's vote is for acquittal, and the trial ends in a tie, acquitting Orestes. In siding with the father' (Agamemnon's) interests rather than the mother's (Clytaemnestra's), Athena cites the fact that "no mother gave her birth," because she was born only of her father, Zeus. The Furies are mollified by being honored henceforth as the Eumenides, the "Kindly Goddesses."

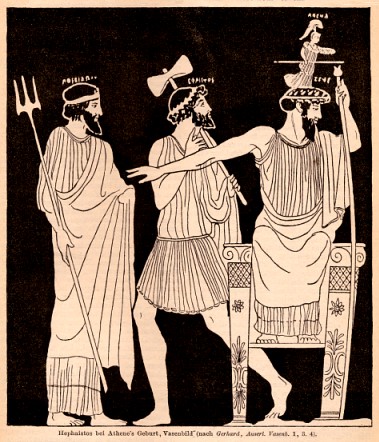

The Council of the Areopagus was a real court in Athens, very ancient and aristocratic, which had special jurisdiction over homicide, but had otherwise lost much of its power by Aeschylus' time. It was, however, much revered by nostalgic conservatives. Athena is literally correct but disingenuous in denying that any mother bore her. In Hesiod's Theogony we learn that she had a mother, Metis ("Good Counsel"), whom Zeus swallowed when she was pregnant with Athena so that she would not bear a son who would depose him, but she would remain inside him to give him advice. The best-known myth has Zeus give birth to Athena from his head (see the illustration above). Here are Athena's words in the Eumenides:

It is my duty now to render the final judgment. |

Quotation for May 2009: Inspired by the current hysteria about "swine flu," we quote Pindar's impassioned defense against the slur "Boeotian pig." |

"Boeotian pig" as an insult

A nasty strain of flu virus has cropped up in many parts of the world, having first been identified in Mexico in a village near a pig farm. Stoked by the media, hungry for sensational stories, a panic of apocalyptic proportions circled the globe with more speed than the disease itself. Fears were raised of a worldwide pandemic killing millions, similar to the devastating flu epidemic of 1918. The disease acquired a popular name: SWINE FLU. While the first outbreak caused a number of deaths, subsequent infections have been, for the most part, no worse than the flu that visits us annually. One reason for the initial virulence may be that both the pig farm and the nearby village were scandalously overcrowded, substandard, and filthy. (Similar conditions caused the severity of the hideous plague at Athens during the Peloponnesian War, where countless refugees were crowded into the city — that epidemic was, of course, not the flu but a different disease.) Public reactions have ranged from obsessive-compulsive to the ridiculous and xenophobic. In some countries, the entire population goes around in (mostly useless) face masks; in others, travel from Mexico and the U.S. is prohibited or restricted. In the U.S., schools are closed to prevent close encounters among students (uselessly, since the young people simply go to sports events or the mall). Most bizarre of all, some people are reported to fear eating pork — or Mexican food!

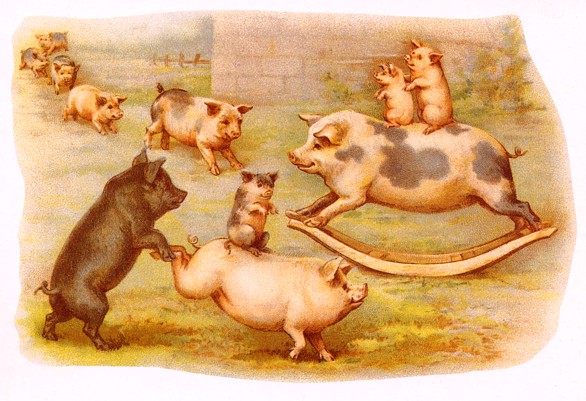

Pigs have always gotten a bad rap, as dirty or stupid (they are by nature neither), or just plain fat. This month, we look at pigs in ancient Greek literature. Circe turned Odysseus' men into pigs, but the swineherd Eumaeus is Odysseus' faithful ally when he gets home to Ithaca and must battle the evil Suitors. Most egregiously, an entire nation is labeled with the swinely epithet in the the phrase BOEOTIAN PIG, first made known to us, uttered in indignation, by the great lyric poet Pindar, from the Boeotian city of Thebes.

Rivalry of Thebes and Athens

Boeotia is a region in central Greece, north of Attica, with much agricultural land (and in antiquity famous for the delicious eels of Lake Copais, which has since been drained), but with little access to the sea. Of its many towns, the greatest was Thebes, site of some of the most glorious narratives in Greek mythology. Here we find Cadmus, founder of the city, who sowed the dragon's teeth (and who, with his wife Harmonia, became, in old age, a snake). His daughter, Semele, became the mother of Dionysos, but was fried by Zeus' thunderbolt. Another daughter, Agave, driven mad by Dionysos, killed her own son, Pentheus, thinking that he was a lion, a story told by Euripides in his Bacchae. Oedipus, whose family is familiar to us in the tragedies of Aeschylus and Sophocles, was likewise king of Thebes. It is ironic that the greatest Theban stories come to us in Athenian versions, as do many of our depictions of the national character of Boeotia. Thebes and Athens were sometimes allies, often rivals (Thebes took the Persian side in the Persian Wars), and the Athenian comic poets in particular delighted in describing Boeotians as sluggish, uneducated, caring only about eating, and with a "lack of feeling" (anaesthesia), i.e for the finer things of life. Even today, the term "Boeotian" is used to imply slowness and ignorance.

Actually, Thebes must have been a pretty interesting place. Far from limiting themselves to the Olympian gods, the Thebans had many unusual cults (including the mystery cult of the Kabeiroi), and were open to other philosophic and mystical ideas, such as Pythagoreanism. Women occupied a more important place in Thebes than at Athens, especially in connection with their religious life. (The receptiveness to strange cults is reflected in Euripides' description of Dionysiac madness in the Bacchae.) Boeotians excelled in music, especially in playing the flute, a talent also mocked by the Athenians. Great poets and writers came out of Boeotia, including Hesiod, the contemporary of Homer who composed the Theogony and Works and Days, from Ascra; the poetesses Corinna, from Tanagra, and Myrtis; Plutarch (46 A.D. - after 120 A.D.) philosopher and biographer best known today for his Lives of eminent Greeks and Romans, from Chaeronea; and greatest of all, the lyric poet Pindar, whose home was the only house spared by Alexander the Great when he sacked Thebes.

Pindar's Sixth Olympian

Pindar's Sixth Olympian Ode celebrates the victory in the mule chariot race by a team owned by Hagesias of Syracuse in (perhaps) 472 B.C. These equine athletes are apparently female, as the word for "they" has the feminine form keinai in line 25. We quoted lines from the poem that celebrate the mules' strength and horse-sense in an earlier "Quotation of the Month" for June 2007, to mark the victory of the filly Rags to Riches in the Belmont Stakes.

Below are the lines from Pindar's Sixth Olympian that refute the piggy insult. (Notes: "Aeneas" is the chorus-master, not the Roman hero. The skutale (which I translate as "enciphered dispatch") was a Spartan device, a staff around which a strip of leather was wound diagonally, upon which a message was written. When removed from the staff, the writing was illegible, but when delivered to its destination, it was rewound around a staff of identical diameter, and could be read.)

. . . I have a feeling of a shrill whetstone on my tongue, |

Bibliography:

Nancy H. Demand, Thebes in the Fifth Century: Heracles Resurgent, London, 1982.

Rhys Roberts, The Ancient Boeotians: Their Character and Culture and Their Reputation, Cambridge (England), 1895.

Sarantis Symeonoglou, The Topography of Thebes, from the Bronze Age to Modern Times, Princeton, 1985. (The title of this book is disarmingly understated, as this volume comprises a thorough history of the city through all its vicissitudes.)

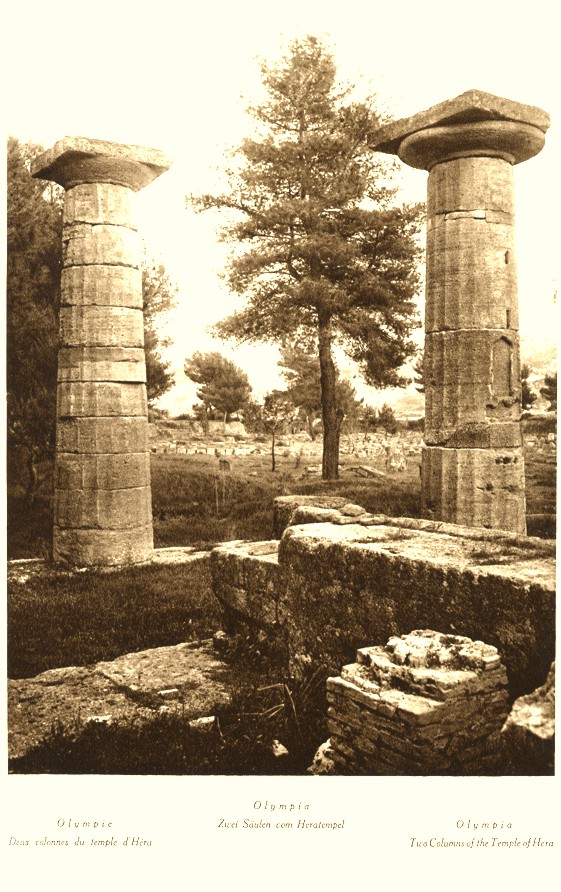

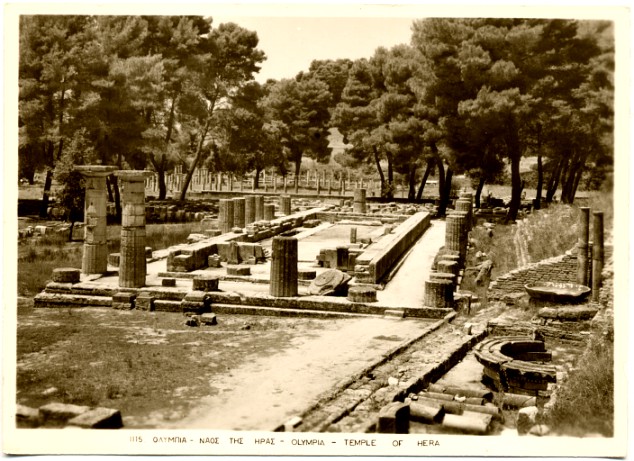

Columns of the temple of Hera, Olympia. (From Hanns Holdt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Griechenland, 3rd edition, 1928.)

Quotation for April 2009: Ovid, in the Fasti, wonders about the name of the month |

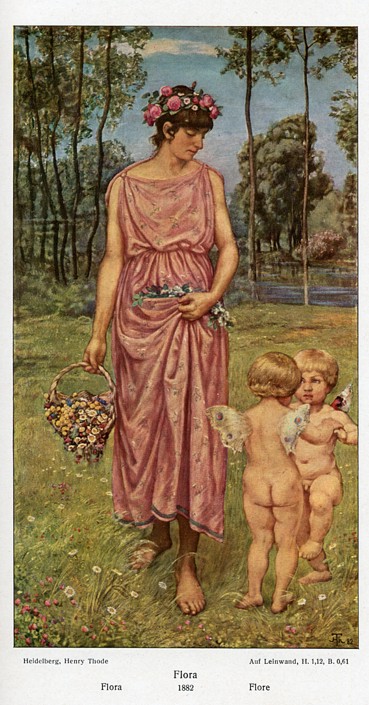

The goddess Flora by Hans Thoma (1882, from Thoma: Des Meisters Gemälde in 874 Abbildungen, Stuttgart, 1909).

Why is April called "April"?

The Roman year, ordained by Romulus, originally began with March; April, sacred to Venus, was the second month. King Numa (about 700 B.C.) added two more months, January, sacred to Janus, the god of openings, and February. Ovid, in his Fasti, or Roman Calendar, Book IV, for April, wonders out loud to Venus why April is not named for her, since the month is sacred to her and to her festival. "They say" ( memorant), Ovid tells her (and us), that the name comes from the fact that April "opens" (aperit) the fertility of the earth from its winter frost. But Ovid himself prefers to think that the name comes from the Greek name for Venus, Aphrodite. The debate continues today. In favor of the first idea is the parallel with the modern Greek word for "spring" anoixis ("opening"), but modern scholars also find a derivation from the name Aphrodite possible, perhaps through the Etruscan form of the name, Apru (although the Etruscans themselves called the month "Cabreas"; see Sarolta Takács, Vestal Virgins, Sibyls, and Matrons: Women in Roman Religion, 2007).

April is an optimistic month (despite T.S. Eliot calling it "the cruellest"). In 2009, Easter, Passover, and Earth Day all were celebrated in April. In the northeastern U.S., we went from winter-like conditions to summer in a few weeks, with all the growing things and flowers coming up from Mother Gaia.

Venus, giver of fertility and culture

In our quotation of the month, Ovid decries the etymology that denies Venus her month, and celebrates her gifts of love, creation, and civilization:

Where does ill-will not find a way to attack? There are those who |

Quotation for March 2009: Solving the world's crises: Heracles cleans the Augeian stables |

Heracles cleaned the stables of King Augeias of Elis by diverting a river through them. (Illustration: View of Hera's temple at Olympia, from an old postcard.)

A Herculean task

A Herculean task, in more than one sense, confronts the Obama administration as it attempts to solve multiple problems and effect multiple reforms in the American economy, infrastructure, and education and health care systems, and as it works to rebuild our position of responsible leadership in the global neighborhood. A sludge of fraud, greed, ignorance, and irresponsibility must be cleaned up, the flow of financial credit unclogged, and public confidence and trust in our public institutions restored.

We are reminded of nothing so much as Heracles' (Hercules') fifth Labor, the cleaning of the Augeian stables.

The Twelve Labors

The Labors of Heracles are described in different versions by many Greek and Roman authors, but a rationalized and comprehensive account is in the Library of Apollodorus (first century B.C. or A.D.?), as follows:

Heracles was driven mad by his stepmother, the goddess Hera, and killed his wife Megara and his children (this incident is placed by Euripides after his Labors in the tragedy Herakles, also called Hercules furens). He went into exile and was purified by Thespius, and inquired of the Oracle at Delphi as to what to do next. The Pythian priestess told him to go to Tiryns and live in servitude to King Eurystheus for twelve years and perform ten labors imposed by him (later increased by Eurystheus to twelve). The twelve Labors were:

- To bring Eurystheus the skin of the Nemean lion.

- To kill the Lernaean hydra, which had nine heads (Diodorus and Ovid said one hundred), which kept regrowing, two for one, as they were cut off. Heracles' nephew Iolaus helped by cauterizing the stumps to keep them from resprouting; one head was immortal, so Heracles buried it with a large rock over it. The many-headed Hydra could be another metaphor for our current crises.

- To bring the Cerynitian hind, which had golden horns, alive to the king.

- To bring back the Erymanthian boar, alive.

- To clean out the stables of King Augeias of Elis, who possessed vast herds of cattle, in a single day. (DETAILS BELOW.)

- To drive away the birds from Stymphalus in Arcadia.

- To bring back the savage Cretan bull. (After showing the bull to Eurystheus, Heracles let it free, and it later turned up at Marathon in Attica, where it harassed the inhabitants.)

- To bring back the man-eating mares of Diomedes.

- To bring the belt of Hippolyte, the Amazon queen. (Because of the meddling of Hera, who caused the Amazons to attack, Heracles ended up killing Hippolyte, an unintended consequence.)

- To steal the cattle of Geryon.

- To steal the golden apples of the Hesperides, which were guarded by a dragon. (Among the many side adventures of this Labor, Heracles also shot the eagle that was devouring the liver of Prometheus, releasing Prometheus from his bondage.)

- To bring back Cerberus, the three-headed dog of Hades. (After showing Cerberus to Eurystheus, Heracles politely returned Cerberus to Hades.)

Heracles performed the original ten Labors in eight years and one month, but Eurystheus imposed another two Labors, disqualifying the Hydra and the Augeian stables, the former, because Heracles had the help of Iolaus, the latter because Heracles was did it for pay.

Cleaning the Augeian stables

Augeias was king of Elis, the district of western Peloponnesos where Olympia is located. He was variously described as the son of the Sun or of Poseidon, and was one of the Argonauts who sailed with Jason. He had vast herds of cattle and sheep, with vast stables to match. Eurystheus commanded Heracles to clean out Augeias' stables in one day, but when Heracles approached Augeias, he said nothing about Eurystheus, and offered to clean the stables in exchange for one tenth of the herd. Heracles diverted the river Alpheus (Apollodorus says the rivers Alpheus and Peneus) through the cattle-yard and cleaned it out. When Augeias learned that Eurystheus had commanded the deed, he refused to pay Heracles, and Eurystheus refused to recognize this exploit among the Labors, as he had performed it for hire. Pindar, in his Olympian Ode X tells how Heracles took revenge on Augeias and his kin, killing them and using the spoils to found the shrine of Olympia and the Olympic games. The official Olympiads begin in 776 B.C., but the discovery of Mycenaean remains at the site lend credence to the belief that Heracles — or somebody! — established the site and the games in very ancient times.

Theocritus Idyll 25 (which may be incomplete and may not be by Theocritus, Syracusan Greek poet of the 3rd century B.C.) describes at great length the arrival of Heracles at the estate of Augeias, through which he is given a "guided tour" by one of the workmen, who then takes him to the king. Here is an excerpt:

Lo, and already the Sun-god's steeds were sloping to westward, |

The capture of the Cerynitian hind was Heracles' third labor. (Illustration: Heracles capturing the hind, Delphi Museum, from a postcard).

Quotation for February 2009: For the financial meltdown and other follies, wisdom from a Cretan knife |

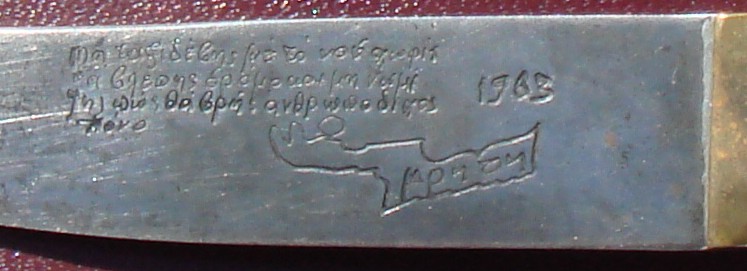

A souvenir knife and sheath from Crete with inscription; close-up of inscription and "map" of Crete. (Photo by J. Sowa.)

Taking a trip into fantasyland

The stock market has crashed, taking investors' life savings. Workers cannot find jobs, and homeowners unable to pay their mortgages are evicted from their foreclosed homes; students have no money for tuition. Bernie Madoff's Ponzi scheme and others like it defrauded investors of billions of dollars, leaving many charities, community groups, and educational institutions without funds. Meanwhile, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (and now Pakistan) drag on and on, draining more resources.

All of these tragedies have one thing in common: the willingness of large numbers of people to live in a fantasy world, following no roadmap of reality. (Some, Cassandra-like, saw the bad news coming but could not stop the folly). Not only was there no Plan B; sometimes there wasn't even a Plan A. Home-buyers took out mortgages they could not afford, thinking that prices could only increase. Banks and mortgage companies made loans (then packaged them and sold them off to other banks), knowing that they could not be repaid but hoped the fun would always last. Investors in Madoff's scheme did not ask how he made his money as long as they could enrich themselves, and Madoff himself thought he could get away with his shenanigans forever. Bush started the war in Iraq with gauzy ideas of destroying Saddam Hussein's (non-existent) WMD's and being greeted by Iraqis with flowers and candies. And Osama bin Laden, whose attacks on America originally set off the war, had equally unrealistic dreams of destroying all of Western secular civilization, while on Wall Street, Western civilization was destroying itself with fantasies of "a new paradigm," where gravity went only one direction — up.

Wisdom on a knife blade

This month, in somewhat of a departure, the quotation is not from ancient Greek but from modern Greek. Years ago, when I was a student in Greece, I bought a knife in Crete, which was very useful on field trips, especially for cutting bread and cheese, and the occasional piece of fruit. It also has engraved upon it a useful little verse, which has many applications. Its homely reminder not to "take a trip with your mind" into daydreams where there is "no road" of reality to follow, literally brings us back to earth, whether the topic is romantic love or untold fame and riches. Better to find a gorgeous road, however rocky, and follow it. If you do not immediately see a road, get a map, or ask for a guide!

The knife is pictured above. Below is the original verse, in transliteration (with the original spacing of nomi-zes), with an English translation:

Mê taxidébês mè tò noú chôrís |

Don't take a trip with your mind unless |

Quotation for January 2009: In honor of the inauguration of President Barack Obama, Vergil's prediction of a new Golden Age in his Fourth Eclogue |

Vergil's idea of Paradise: Dyers will no longer have to dye wool, because sheep will already come in different colors. (Illustration: with multicolored apologies to Hans Thoma (German, 19th century), "Under Olive Trees near Tivoli," 1880, from Thoma: Des Meisters Gemälde in 874 Abbildungen, Stuttgart, 1909.)

A new Golden Age

In the ecstasy surounding the elevation of Barack Obama to the office of President of the United States, it seems impossible that any mortal man (or even a committee of mortal men and women) can deliver on the promise of his astounding victory. The wish list is endless: restoring a shattered economy; rebuilding our decaying infrastructure and (we hope!) catching up with Europe and Japan in high speed rail and transit; healing our urban neighborhoods; bringing peace to the Middle East; protecting the environment and reversing global warming; not to mention restoring America's reputation as a leader, role model, and willing cooperator among the nations of the world.

This month's quotation is from Vergil's 4th Eclogue, the so-called "Messianic" Eclogue. Among the pastoral fantasies of the Eclogues it stands out. It is addressed to Vergil's friend and fellow poet Pollio, who had been elected consul and had helped broker the Treaty of Brundisium between Antony and Octavian which, it seemed, would finally bring peace to the Roman world after decades of civil war. It didn't, of course; Antony, after becoming involved with Cleopatra, was vanquished at Actium in 31 B.C. by Octavian, who became the Emperor Augustus.

A Wonder Child and purple sheep

Vergil envisions a new Golden Age marked by the birth of a marvellous Child, who will grow to great manhood beloved of the gods. Vergil never specifies who this Child is, or who his father is. Is it Pollio? or Antony? or Octavian? Perhaps diplomacy, or caution, persuaded Vergil to be vague. Octavian's newborn, in fact, turned out to be a girl (the notorious Julia). Some Christian writers (who, like Dante, tend to make Vergil a kind of honorary Christian) have seen parallels to Isaiah and insist that Vergil was prophesying the birth of Christ. The poem foretells the return of "the Virgin," but the reference is undoubtedly to Justice, the last of the immortals to leave Earth when men became evil. Vergil's influences include the Sibylline Books, supposed to contain the oracular utterances of the Sibyl of Cumae, Pythagorean philosophy, and perhaps even Jewish Messianic prophecies that were in the air.

Vergil depicts an earthly Paradise, which frankly gets quite silly. Not only does he describe crops that grow by themselves and goats and cattle that come to be milked of their own accord, but he includes the fact that wool will not have to be dyed ("wool will not have to lie about its color") because sheep will obligingly change their own colors to shades of yellow, purple, and vermillion (see my interpretation in the illustration above).

A Roman moment

At President Obama's inauguration, Chief Justice Roberts got the words wrong in the Oath of Office, whose words are decreed in the Constitution (our sacred document!). Although both he and Mr. Obama eventually recovered and said the correct words, it was later felt necessary, in a private White House ceremony, for them to repeat the entire Oath, to make sure that it was valid. How very Roman! For in Roman religion, the words of ritual had to be letter perfect, or else the entire ceremony had to be repeated. There may be elements of magic in this, as if the words themselves have the power to bring about a result, or perhaps a feeling that an "impurity" in the wording could offend the deity (see W. Warde Fowler in "The Religious Experience of the Roman People," 1911, reissued 1971).

This month's quotation was suggested to me by Marilyn Skinner of the University of Arizona. If anyone has suggestions for future quotations, I'd be glad to hear them.

Here, in translation, are the opening lines of Vergil's 4th Eclogue:

Sicilian Muses, let us sing of somewhat more important matters. |

---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2008 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: