These are quotations for the year 2006. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

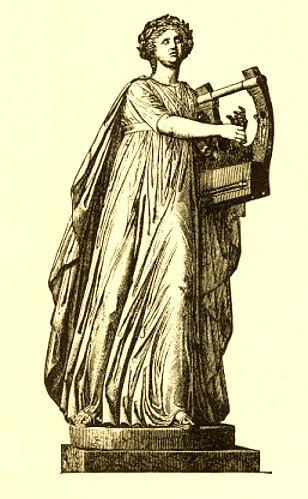

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2006, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2006 |

Below are quotations for the year 2006. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2006

Click on a link to read each quotation

2006

- December '06 for the Saturnalia, quotations from Catullus and Vergil's Aeneid (on the Golden Age of Saturn).

- November '06 For Veterans' Day, a quotation from Horace's Odes on courage and patriotism.

- October '06 the rainy stars of the Hyades in autumn, from Hesiod's Works and Days.

- September '06 The god Pluto, his planet, and his dog. Quotations from Aeschylus (Pluto's gold-flowing river); Plato (the name "Pluto" ("the Wealthy One") as a euphemism for the God of the Underworld); Euripides (Cerberus, Pluto's three-headed guard dog).

- August '06 the god Pan and the Persians at Marathon, from Herodotos' Histories: (Pheidippides, who ran to Sparta for aid to Athens, and the runner who carried the news of the victory at Marathon were two different messengers, but are often confused -- and neither of them fell down dead; these guys were professionals, after all!)

- July '06 a warning about the dangers of disturbing Pan at mid-day, from Theocritus' Idyll I.

- June '06 Ovid's story (from the Fasti, or "Roman Calendar") about how June was named for the goddess Juno -- if it wasn't named for one or another rival goddess!

- May '06 Quotation for Memorial Day: Excerpts from Pericles' Funeral Oration (for the Athenian war dead), in Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War.

- April '06 Quotations for Earth Day: Gaia in Hesiod's Theogony and Homeric Hymn III to Earth, Mother of All.

- March '06 The story of Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Mars, for whom the month of March is named, from Ovid's Fasti.

- January-February '06 Quotations about Blacks in antiquity for Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Black History Month (from Homer, Vergil, Terence).

Quotations for December 2006, from Catullus and Vergil, for the Saturnalia |

The remains of Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, view from the Capitoline Hill. The Temple of Castor and Pollux (three remaining columns) is on the right. (From an old postcard.)

On the Saturnalia, best of days!

(-Catullus 14.15)

Saturn, the ancient and mysterious god

The Saturnalia, one of the precursors of Christmas, was celebrated at Rome on December 17, in honor of the god Saturn. It was known for great jollity. Slaves were treated as equals of their masters, and gifts were exchanged, especially little pottery figurines called sigillaria.

Saturn was a very ancient god, whose origins are clouded in enigma. One theory connects his name with the Latin satus "sowing," on the assumption that his festival celebrates the end of the fall planting. There was a Roman belief that Saturn was a Greek import (identified with Kronos). He was believed to have come to Latium in the reign of the god Janus, fleeing from the wrath of Jupiter, and that he brought agriculture and civilization to the Latins, who afterwards worshipped him as a god. Another theory holds that Saturn was of Etruscan origin. The temple of Saturn, located at the western end of the Forum, just below the Capitol, was one of the most ancient temples in the Forum, although the temple whose columns we see today is late, perhaps built after the fire of 284 A.D. (see the illustrations at the top and bottom of this entry).

The Golden Age

In Vergil's Aeneid, King Evander, himself an exile from Arcadia, shows Aeneas, just arrived in Italy from Troy, the future site of Rome. (Evander's own settlement is called Pallanteum, which Vergil manages to connect with the name of the Palatine Hill.) Evander describes the arrival of Saturn, whose reign was the mythic Golden Age:

Then King Evander, founder of the Roman citadel, spoke:

"The indigenous Fauns and Nymphs inhabited these woods,

and a race of men born from the trunks of the hardy oak.

They had no customs, no civilization; they did not know

how to yoke oxen or acquire wealth or save what they produced,

but the fruit of trees and the difficult livelihood of hunting nourished them.

It was Saturn who first came from heavenly Olympus,

fleeing the weapons of Jupiter, an exile who had lost his kingdom.

He united this race, untutored and dispersed among the high mountains,

gave them laws, and chose that the place be called Latium,

because it was on these shores that he had safely lain hidden [latuisset].

"Golden" is the name given to the age in which he ruled.

Thus he reigned in placid peace,

until, little by little, an inferior age of another color,

and the madness of war and greed for possessions succeeded it. . ."

(Vergil, Aeneid 8.312-327)

The Roman Forum, another view, looking toward the Capitoline Hill, with the columns of the Temple of Saturn in the middle, toward the back. The columns of the Temple of Castor and Pollux are on the left. (From an old postcard, before 1907).

Quotation for November 2006, from Horace, for Veterans' Day |

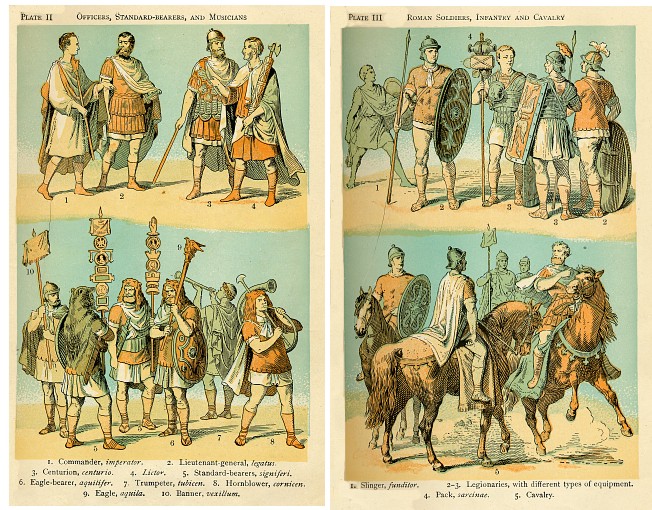

Roman soldiers, illustrations from Caesars' Commentaries, ed. Francis W. Kelsey, 1918.

This month's quotation is an ode on courage and patriotism by the Roman

poet Horace (65-8 B.C.). It is appropriate for Veterans' Day (November 11),

when we honor the soldiers of our country, past and present. The most famous

words of the ode, Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori ("It is

sweet and fitting to die for one's country") are inscribed over the west

entrance to the Memorial Amphitheater at Arlington National Cemetery.

|

Angustam amice pauperiem pati robustus acri militia puer condiscat et Parthos ferocis vexet eques metuendus hasta vitamque sub divo et trepidis agat in rebus. illum ex moenibus hosticis matrona bellantis tyranni prospiciens et adulta virgo suspiret: "eheu, ne rudis agminum sponsus lacessat regius asperum tactu leonem, quem cruenta per medias rapit ira caedes." dulce et decorum est pro patria mori, mors et fugacem persequitur virum, nec parcit imbellis iuventae poplitibus timodove tergo. Virtus, repulsae nescia sordidae, intaminatis fulget honoribus, nec sumit aut ponit secures arbitrio popularis aurae. Virtus, recludens immeritis mori caelum, negata temptat iter via, coetusque vulgares et udam spernit humum fugiente pinna. est et fideli tuta silentio merces: vetabo, qui Cereris sacrum volgarit arcanae, sub isdem sit trabibus fragilemque mecum solvat phaselon; saepe Diespiter neglectus incesto addidit integrum, raro antecedentem scelestum deseruit pede Poena claudo. |

Let the youth, hardened by stern military service, learn willingly to endure the straits of deprivation and let him, as a horseman feared for his lance, harass the fierce Parthians, and may he live his life beneath the open sky in perilous situations. Looking out at him from the enemy battlements, the lady consort of the warring tyrant and the grown maiden might sigh, "Alas, let not our royal bridegroom, inexperienced in the movements of the army provoke the lion, fierce to the touch, whom rage for blood propels through the midst of the slaughter." It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country, but death also pursues the man who flees, nor does it spare the knees and timid backs of unwarlike youths. Virtue, unknowing of sordid defeat, gleams with unsullied [public] honors and neither assumes nor sets aside the [official's] axes according to the breezes of popular opinion. Virtue, opening the heavens for those who do not deserve to die, makes its way by a path denied to others, spurning the vulgar crowd and the damp earth on fleeting wing. There is a sure reward for faithful silence, too. I shall forbid the man who has divulged the rites of arcane Ceres to abide beneath the same roof or unmoor a fragile boat with me. Often Jupiter, when offended, has involved the innocent with the guilty, but rarely does Punishment desert the scoundrel, though he has a head start, and she proceeds with halting gait. (- Horace, Odes, III.2) |

The grave of my ancestor Silas Angier (1737-1808), Revolutionary War veteran, in the cemetery in Fitzwilliam, NH. The gravestone is modern, probably replacing an original stone, now vanished. Some of his other descendants are in the background. (Photo by C.A. Sowa.)

Quotation for October, 2006: the rainy stars of the Hyades in autumn, from Hesiod's Works and Days |

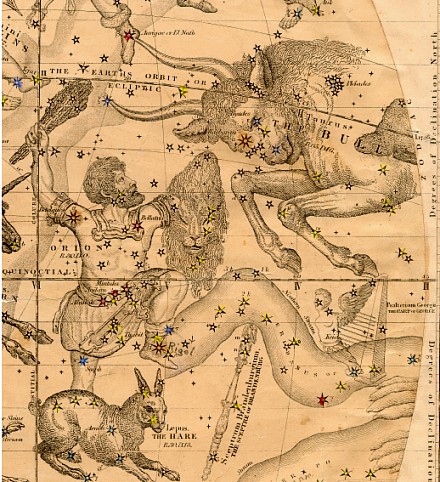

The constellations of Orion and Taurus, showing the Hyades and Pleiades in the head and shoulders of the bull, detail from Burritt's Geography of the Heavens, 1856.

This month's quotation is from Hesiod's advice to farmers in the Works and Days, suggested by a stretch of soggy, rainy weather that has beset the Northeast following a blazingly clear Columbus Day weekend.

The Pleiades and Hyades are star clusters in the constellation Taurus. Their setting in late October or early November were seen as signs of rain. In mythology, the seven Pleiades and five Hyades (actually, there are many more, but most are not visible without a telescope) were nymphs, daughters of Atlas. The Hyades were portrayed as the nurses of Dionysos, or in another myth, as the brothers of Hyas, who was killed while hunting, and who cried themselves to death. The name "Hyades" probably comes from the Greek verb huo "to rain" (though the Romans thought it came from the (also Greek) hus "pig," translating the name as suculae "the Piglets.") The name "Pleiades" may be related to the verb pleo "to sail," though Hesiod's advice indicates that the Pleiades at this time herald anything but good sailing. In the Mediterranean lands, as in the American Southwest, the rainy season (and thus the growing season) begins in November and extends into the springtime.

When the Pleaides and Hyades and strong Orion

begin to set, then be mindful of ploughing

in good season. Then the year's work is put away beneath the earth.

But if a desire for stormy seafaring seizes you,

when the Pleaides, fleeing strong mighty Orion,

plunge into the misty sea,

then blasts of all kinds of winds rage.

And then you should no longer have ships on the wine-dark sea,

but remember to work the earth, as I bid you.

"Rocks of the Strophades," engraving from H.W. Williams, Select Views in Greece, 1827.

Quotation for September, 2006: The god Pluto, his planet, and his dog |

Statue of the god Hades (Pluto) with his dog Cerberus, in the Villa Borghese, in an illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890. In this depiction, Cerberus has only one head, not his usual three (contrast the illustration below).

Astronomers, with more snobbery than common sense, have decided that the ninth planet, Pluto, is not a planet at all, but something called a "dwarf planet." Now it seems that, since a person like the actor Peter Dinklage, who is a dwarf (and who was great in "The Station Agent") is very much a person, a dwarf planet is still a planet. Pluto is round and orbits the sun, which fits the description of a planet. It has a weird orbit, and if we want to be politically correct, perhaps we should call it a "differently abled planet," or a "special planet." In fact, several other "dwarf planets" have been identified. Let diversity reign. Astrology (which admittedly is more folklore than science) tells us that Pluto is important to the horoscopes of people born under the sign of Scorpio. I, as a Scorpio, therefore take the situation very personally. In any case, despite some hysteria from fans of Pluto, Pluto has not died. Like the Disney bloodhound of the same name, it still faithfully patrols the outer reaches of the solar system.

Pluto the planet was discovered in 1930 by American astronomer Clyde Tombaugh, and was named for the Greek god Pluto. The name was given by Venetia Phair, who was then an 11- year-old Oxford schoolgirl. Ms. Phair (née Burney), now 87, still lives in Surrey, England. Her great uncle Henry Madan, as it happens, gave names to Phobos and Deimos ("Fear and Terror"), the moons of Mars, the planet named for the god of War. Pluto, Mickey Mouse's dog, was named for the planet, not the other way around. The dog motif is appropriate (see below).

Pluto is the god of the Underworld, also known as Hades (in Greek mythology, Hades is the name of the god, not the Underworld itself, which is denoted by the possessive Haidou, "Hades' [place]"). He is the brother of Zeus, Poseidon, Hera, and Demeter. He is famous for kidnapping Persephone, daughter of Demeter, to be his consort in the Underworld. The name Pluto (Plouton) probably comes from the word ploutos "wealth," and is sometimes explained as "giver of wealth," for the precious metals and crops that originate beneath the earth. In Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound, Prometheus, chained to a rock by Zeus for giving fire to man, is visited by the maiden Io, as she races past him. Io, a girlfriend of Zeus, has been turned by him into a cow and is pestered by a gadfly, courtesy of Hera, Zeus's jealous wife. Prometheus foretells to Io her future wanderings, including the following warning:

. . . [Beware of] the one-eyed army of the

Arimaspians, who ride on horses, and who live by the gold-flowing

stream of Pluto . . .

(- Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound lines 104-106)

But Plato, in his Cratylus, in which he proposes many etymologies, some perhaps correct, some incorrect, thought it likely to be an apotropaic ("turning away [evil]") name, used to avoid uttering the real name of an abhorred entity. In the same way, many European languages (including English) call the bear by some name ("bear," "bruin") that means "the brown one," instead of the Indo-European word for the animal, which is preserved in the Greek arktos (a word that survives in the English "Arctic," for the constellation of the Great Bear). Actually, if the name Hades means "the Unseen One" or "He who Makes Invisible," this name too could be a way to avoid saying the name of Death, or Thanatos.

. . . Pluto gives wealth (ploutos), and his name means the giver of wealth, which comes out of the earth beneath. People in general appear to imagine that the term Hades is connected with the invisible (aeides); and so they are led by their fears to call the God Pluto instead.

(- Plato, Cratylus 403a, Jowett translation)

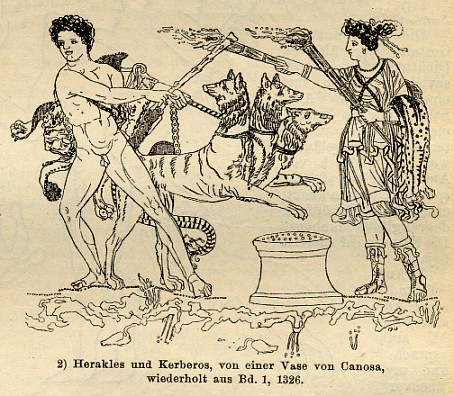

Pluto's mascot is Cerberus, the fierce dog usually depicted with three heads (Hesiod, in the Theogony, gives him fifty heads!) Cerberus was friendly to all who entered the Underworld, but attacked and bit anyone attempting to leave. Heracles, as one of his Twelve Labors, brought Cerberus up from the Underworld, as illustrated by the vase painting shown below. Our last quotation is from Euripides' Alcestis. Admetus, king of Pherae in Thessaly, is fated to die, but the god Apollo makes a deal with Death (Thanatos) that Admetus can live if he finds a substitute to die for him. All of Admetus' friends, and even his parents, refuse, but his beloved wife Alcestis agrees to die, and Admetus selfishly accepts. In this quotation, he addresses his departed wife, comparing his plight to that of the singer Orpheus, who charmed the spirits of the Underworld into releasing his dead wife, Eurydice, only to lose her when she looked back. Euripides' play ends happily, when Heracles restores Alcestis to her husband. But before this happy ending, Admetus laments:

. . . But if I had the tongue and melody of Orpheus,

so that, calling with hymns upon Demeter's daughter and her husband,

I could bring you back from Hades' house,

I would descend, and neither Pluto's dog

nor Charon with his oar, guide of souls,

would hold me back, before I brought your life once more to light.

(- Euripides, Alcestis lines 357-362)

Detail of a vase painting, Heracles and Cerberus, from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie.

Quotation for August, 2006: the god Pan and the Persians at Marathon, from Herodotos' Histories |

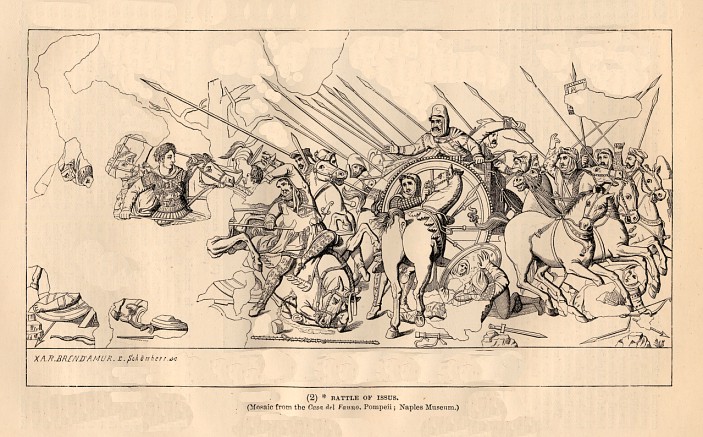

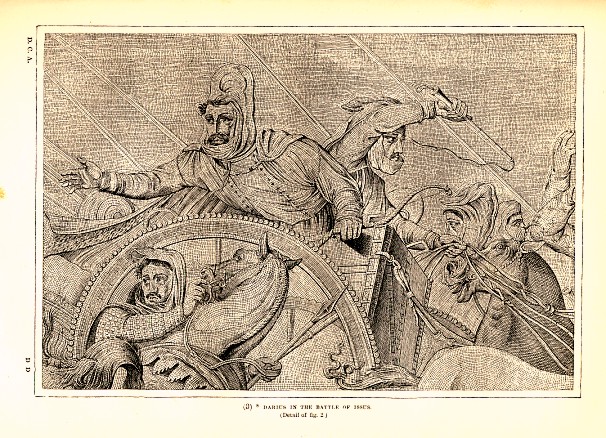

Mosaic of Darius in battle, from the Casa del Fauno at Pompeii, redrawn.

The Persian Wars

The Persians, now known as the Iranians, are in the news again today. In antiquity, too, tensions arose between the Persians and their European neighbors over control of the eastern Mediterranean. In the early fifth century B.C. these tensions spilled over into the "Persian Wars" between the Greek states, led by Athens and Sparta, against the incursions of the Persians, first under Darius, then climactically, under Xerxes. The first part of fifth century Greek history was dominated by the Persian Wars, the last part by the Peloponnesian War between the Greek states (Athens and her allies and Sparta and her allies) with an intervening period of relative peace -- and Athenian expansionism -- in between.

The battle of Marathon (490 B.C.) was the climactic battle of the first phase of the war, in which a large Persian force under Darius was defeated by an outnumbered force of Athenians and Plataeans, through an exercise of superior tactics and strategy. The second phase of the war was the larger invasion by Darius' son Xerxes. In the second phase, in the battle for the northern pass at Thermopylae ("Hot Gates," for its sulphur springs) in 480 B.C., it was the Spartans who won immortality by their bravery, leaving as their epitaph (in which the Spartans are called by their other name of Lacedaemonians) the following:

O stranger, go tell the Lacedaemonians thatThe Persians were finally and definitively driven out of Greece in the sea battle of Salamis (480 B.C.) and the land battle of Plataea (479 B.C.).

we lie fallen here, obedient to their commands.

The Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon did not end the Persian Wars, but it established the prestige and self-confidence of Athens, and it became part of mythology, both ancient and modern. Before the battle, the Athenians sent to Sparta, who was then their ally, for reinforcements. They sent a professional courier, a fast runner named Pheidippides (more correctly "Philippides"), who covered the 150 miles between Athens and Sparta in a remarkable two days. The Spartans were unable to send troops in time for the battle, but Pheidippides reported that as he ran through Arcadia he met the half man-half goat god Pan, who wanted the Athenians to pay him greater worship and promised in return to help them. The Athenians did build him a shrine, and Pan was said to have caused a panic -- the terror caused by Pan -- among the Persians.

After the victory at Marathon, the Athenians may have dispatched another messenger to carry the news to Athens. This man, whose identity is unknown, is often confused with Pheidippides. In any case, the Athenian army was mostly intent on marching back to Athens to head off another attack by the Persians, whose ships were seen sailing off toward the now undefended city. The Persians sailed away, and the mythic run of the nameless messenger is commemorated in the modern "marathon" of 26 miles 385 yards, the approximate distance between the beachhead at Marathon and Athens.

The truth about Pheidippides (he survived! -- and there were two different messengers!)

Pheidippides probably was not the messenger who delivered the news from Marathon to Athens (this would have been a short run for a man of his endurance), and he didn't drop dead afterward. That melodramatic touch (and the confusion between the two couriers) was a fiction perpetrated by the Victorian poet Robert Browning, whose version unfortunately survives in modern retellings. While the Battle of Marathon was a historic turning point, we should not forget the actual feat of the real Pheidippides in his run to Sparta, and his magical encounter with the weird woodland god Pan. There is more about Pan, and his ability to cause panic, in the quotation of the month for July, which is repeated below.

Herodotos' account of Philippides (Pheidippides)

Here is the description in Herodotos of Philippides' encounter with Pan:

And first, while they were still in the city [before leaving for Marathon to do battle with the approaching Persians], the generals sent to Sparta a messenger, Philippides, an Athenian, a professional long-distance courier (hemerodromos, "day-runner"). According to Philippides himself, as he reported to the Athenians on his return, when he was near Mount Parthenium, above Tegea, the god Pan accosted him. Philippides said that Pan shouted out his name, and told him to ask the Athenians why they paid him no attention, when he was kindly disposed toward them and had helped them, and would help them again in the future. And so the Athenians, when their affairs were once again in good order, since they believed in the truth of the report, founded a shrine to Pan under the Acropolis, and celebrate him, in accord with his request, with yearly sacrifices and a torch race.Herodotos Histories Book 6, 105

Darius in battle, detail of the mosaic illustrated above.

Quotation for July, 2006, for a summer afternoon, a warning about Pan from Theocritus' Idyll I |

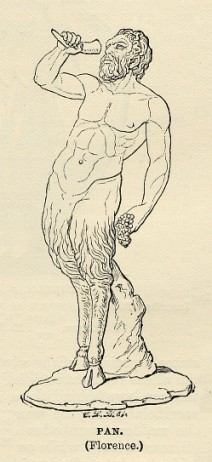

Statue of the god Pan, from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical

Antiquities, 1899.

Watch out for Pan at mid-day!

In the heat of summer, we find it convenient to emulate the Mediterraneans in taking a rest in the noonday heat, rising later to resume our work or leisure. It is a wise idea for another reason, for at that time the god Pan relaxes from hunting, and he becomes angry if disturbed. The word panic literally describes the terror that this weird woodland god can inspire. The Homeric Hymn XIX to Pan (ca. 750 B.C.) tells of his birth in Arcadia as son of the god Hermes and a nymph ("daughter of Dryops" -- the name means "Oak-face," obviously a forest divinity). The infant Pan is born with goat's feet, horns, a propensity for laughing and making noise -- and a full beard! His nurse runs away in horror, but his father Hermes, a trickster god himself who played practical jokes the same day that he was born (Homeric Hymn IV to Hermes), is delighted. Typically of the folk-etymologies of the Hymns, the poem connects the god's name with the word pan meaning "all," because he brought pleasure to all the gods. More likely, the name is related to the word for "pasture," indicative of his country roots. His chosen instrument is the Pan-pipe.

Theocritus (3rd century B.C.), from Syracuse in Sicily, wrote bucolic or pastoral poetry in a much later era, using the Doric dialect of Greek. His rustic Idylls were later the inspiration for Vergil's Eclogues. His first Idyll is a conversation between a shepherd and a goatherd. The shepherd, Thyrsus, asks the goatherd to play something on his syrinx, or Pan-pipe. But the goatherd refuses, for it is noon, and Pan will be annoyed. So instead, the shepherd recounts the story of how the herdsman Daphnis died, driven to death by Aphrodite when he spurned her attempt to make him fall in love. Below is an excerpt from the beginning of the poem:

Thyrsis (a shepherd):

Sweet is the whispering, O goatherd, of yon pine,

that makes music beside the springs. Sweetly, too,

you play your pipes. Second only to Pan, you shall win the prize.

If he wins the horned he-goat, you shall take the she-goat.

But if he takes the she-goat as a prize, to you will fall

the kid. The she-kid's meat is good, before it is old enough to milk.

. . .

I beg you, by the Nymphs, I beg you, goatherd, sit here,

by this steep hillock and the tamarisk tree,

and play your pipes. I, meanwhile, will tend your goats.

Goatherd:

It is not allowed, O shepherd, it is not allowed at noontime

to play the pipes. We fear Pan. For at that time he rests,

weary, from hunting. He is mean,

and bitter anger sits always in his nostrils.

But, Thyrsis, you know how to sing of the suffering of Daphnis,

for you approach most closely to the bucolic Muses.

Let us sit down under this elm, opposite Priapus

and the Fountain-nymphs, where the Shepherd's Seat

and the oak trees are. If you sing

as you once sang in competition with Chromis of Libya,

I will give you three milkings of a goat that has born twins

-- yet while having two kids, she can fill two extra pails --

and I will give you, besides, a deep drinking cup . . .

(-Theocritus, Idyll I, vv. 1-27, translated by C.A. Sowa)

"The Great God Pan," wood carving by Christine Cooper Angier, ca. 1935.

Quotation for June, 2006, from Book 6 of Ovid's Fasti ("The Roman Calendar"): Was June really named for Juno? |

Statue of Juno in the Vatican, from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.

Juno claims that the month of June was named for her, but other goddesses disagree

Our quotation for June is from Ovid's Fasti ("The Roman Calendar"). It is an excerpt from a conversation the poet has with the goddess Juno, who claims that the month of June was named for her. The goddess is in a bad mood. She is jealous over the love affairs of her husband Jupiter (Jove); she refers to Maia, goddess mother of Mercury by Jupiter, as "a concubine." She is also still smarting over the choice by Trojan Prince Paris, son of King Priam, of Venus over both her and Minerva in the famous beauty contest. Venus rewarded Paris with Helen of Troy, leading to the Trojan War. Juno wants Ovid (and the world) to know how important she is and how widely worshipped she is not just in Rome but in other Italian towns. But Ovid and Juno are joined by two other goddesses, both of whom claim that the month was named for them.

In this passage, Ovid parodies many things (he was, after all, the author of the tongue-in-cheek Amores and Ars Amatoria). He parodies the Prologue to Hesiod of Ascra's Theogony, in which Hesiod, "the teacher of plowing" (a reference to his other poem, The Works and Days) meets the Muses, who teach him to sing. Parodying the Muses' warning that "We know how to tell many lies that are like reality, but we also know, when we wish, how to speak the truth," Ovid tells us "I shall sing the truth, but some will say I lied." He also makes the incestuous relations within the family of the gods seem sublimely silly as Juno describes her relationship to Jupiter -- both wife and sister; she can't decide which makes her prouder!

We quote below the beginning of Juno's rant. She is countered by the goddess Juventas ("Youth," in Greek Hebe), wife of Hercules, who says that June was named for her, and by Concord, who claims that the name of June honors the joining (or junction) between the Italian kingdoms of Tatius and Quirinus.

Ovid wisely does not decide between his three goddesses, avoiding the mistake of Paris. For, he says, two goddesses can destroy more than one goddess can bestow.

This month, too, has a name whose origins are in doubt.

I will lay them all out; you may choose the one you like.

I shall sing the truth; but some will say I lied,

thinking that no deities were ever seen by a mortal.

There is a god within us; when it stirs us, we become warm.

This impetus contains the seeds of sacred inspiration.

It is particularly right for me to see the faces of the gods,

whether because I am a bard, or because I sing of sacred things.

There is a grove, dense with trees, a place remote

from any voice, except for the obstreperous noise of water.

There I was wondering what were the origins of the month just begun,

and was meditating on its name.

Lo, I saw the goddesses, not those whom the teacher of plowing

saw, when he followed the Ascraean sheep,

nor those whom the son of Priam judged in the valleys of watery Ida.

One of them, nevertheless, was one of these.

Of them there was one, who was the sister of her husband.

It was she (I recognized her!) who stands in Jove's citadel.

I trembled, and betrayed my feelings by my silent pallor.

Then the goddess removed the fear she had herself caused.

For she said, "O bard, founder of the Roman year,

who have dared to relate great things in slender meters,

you created for yourself the right to see the celestial divine spirit,

when it pleased you to treat the festivals in your verses.

But lest you be ignorant and be led astray by the error of the multitude,

June takes its name from my name.

It is something to have married Jove, and to be Jove's sister.

I don't know if I am prouder of him as brother, or as husband.

If my ancestry is considered, I was the first child to make Saturn

a father, being Saturn's first fated offspring.

Rome was once known as Saturnia, after my father;

for this was the first land he came to after heaven.

If it is the marriage bed that counts, I am called wife of the Thunderer,

and my temple is joined to that of Tarpeian Jove.

If they could give the name of [Jove's] concubine to the month of May,

is there something wrong with giving me a like honor? . . .

. . .

(-Ovid, Fasti, Book 6, vv. 1-36, translated by C.A. Sowa)

Quotation for May, 2006, for Memorial Day: from Pericles' Funeral Oration in Thucydides' Peloponnesian War |

The Parthenon after a rare snowstorm, photo by C.A. Sowa.

Fall in love with your great city

On May 29, we celebrate Memorial Day, when we honor those who have died in war. The quotation for this month contains excerpts from Pericles' Funeral Oration, delivered in memory of fallen Athenians, as recreated by Thucydides in his history of the Peloponnesian War.

Pericles, the great Athenian leader, gave his oration in 431 B.C. at the end of the first year of the war, which was fought between Athens and her allies and Sparta and her allies. In the first part of the speech, Pericles extols the virtues of Athens, and presents a gleaming portrait of his city's view of herself, with her democracy, her bravery, and her material success. Athens is the model for every city -- the educator of all Hellas and of the world.

Sadly, little more than a year later, Pericles was dead of the plague that gripped Athens, overcrowded with refugees who streamed into the city from the countryside. The war itself ground on for another twenty years, bringing strife and political turmoil both within and without Athens, and marked by faction and misguided military adventures. Sparta technically won the war, but Athens survived as a cultural center, giving us the likes of Plato and Aristotle. Athens, of course, is still very much there today, the capital of modern Hellas, a vibrant European city, whose inhabitants still speak (with a few minor changes in pronunciation) the language of Homer and Plato.

...Summing up, I say that the whole city [of Athens] is the school of Greece. To me it seems that among us each man, under the most varied circumstances and with only himself to depend on, is most able to offer himself with grace and versatility. And that this is no boast in words for the moment, but the truth of deeds, is shown by the power of the city, acquired by these habits. For it alone among cities of today comes to the contest greater than its reputation, and alone offers no reason for shame to an enemy because of who has defeated him, nor any sense of blame among its citizens that they are ruled by those not worthy......And so these men died in a manner befitting the city. You who survive must pray that your resolve have a safer outcome, while determining to be no less bold against the enemy. Do not be moved only by words, when you contemplate the advantages derived from defending the city, although one might well expound at length even to you who are knowledgeable, but gazing every day upon the city's greatness, become her lovers, and when she seems glorious to you, reflect that it was by daring, by knowing what was necessary, and by their sense of honor that these men obtained all this; and even when they failed in some attempt, they did not think it right to deprive the city of their valor, rather offering it to her as the best contribution they could make. For having given their lives in common, they individually received the renown that never grows old, and a distinguished tomb, not the one in which they lie, but the one in which their fame, ever-remembered, remains upon every occasion that it is commemorated in word or deed. For famous heroes have the entire earth as their tomb; not only do inscriptions on columns in their own land declare their deeds, but even in foreign lands an unwritten memorial dwells not in material form but within the thoughts of all...

(-Thucydides, from the Funeral Oration of Pericles, in Book II of The Peloponnesian War, translated by C.A. Sowa)

Quotations for April, 2006, for Earth Day: Gaia in Hesiod's Theogony and the Homeric Hymn to Gaia |

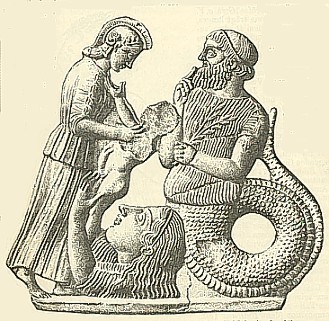

The goddess Gaia, rising from the ground, hands the child Erichthonios

("Born of the (Athenian) soil") to Athena, as serpent-tailed King Kekrops

looks on, from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen

und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.

Gaia, mother of all

April brings us occasions of rebirth and celebration. Easter falls this year on April 16 and Passover extends from April 13-19. Earth Day is celebrated on April 22.

We present two quotations for Earth Day, translations of an excerpt from Hesiod's Theogony and of the complete Homeric Hymn XXX to Earth, Mother of All.

In Hesiod's Theogony (ca. 750 B.C.), Gaia (Earth) is the second oldest divinity, outranked in age only by Chaos. We should remark that Chaos, in Hesiod's cosmogony, is not an undifferentiated mass of primordial matter but a distinct entity, a place ("The Yawning Chasm") whose location is unclear, but is possibly underneath the Earth. Chaos is also a goddess, who gave birth to Night, who in turn gave birth to Day. Gaia herself gave birth to Ouranos (Heaven), the Hills, and the Sea. Ouranos becomes the husband of Gaia. Hesiod begins his cosmogony thus:

Yea verily, first Chaos came into being, but next came

broad-breasted Gaia, the unshakeable foundation of all ...

(Hesiod Theogony ll. 116-117)

With Ouranos as her husband, Gaia became ultimately the mother or ancestress of many gods and goddesses, including Olympians like Zeus and Hera, as well as nymphs, monsters, and strange critters such as the one-eyed Cyclopes and the mighty Hundred-Hands. During the course of the Theogony's more than one thousand verses, Gaia participates actively in the politicking and internecine strife of the gods, as well as helping to sort out their relationships.

The Homeric Hymns are anonymous poems from about the same time as Hesiod and Homer, but sunnier than Hesiod, lacking his weirdness. Unlike the longer Hymns, which tell complete myths, the Homeric Hymn XXX to Earth, Mother of All is one of the shorter invocations. Here, Gaia is the "eldest" of all beings, and the giver of all good things to mankind. The final tag line "But I will remember you and another song, also" is found (with variations) at the end of many of the Hymns. In his parting greeting, the singer of this song is careful to ask the goddess for his idea of the good life -- a prosperous career as a bard!

Gaia, mother of all, I shall sing of you, the well-founded,

the eldest, who feeds all things that are upon the earth,

both those that go upon the divine earth and upon the sea

and those that fly; all these are fed from your wealth.

From you, men become goodly in their children and goodly in their harvests,

Mistress, and it is yours to give the means of life and to take it away

from mortal men. He is fortunate, whom in your heart

you freely honor. He has everything in abundance,

his life-bearing farmland is heavy with harvest, and in his fields

he prospers in cattle, and his house is filled with fine things.

Such men rule with good laws over their city of beautiful women

and great wealth and riches accompany them.

Their sons exult in youthful high spirits

and their daughters disporting themselves in flower-bedecked dances

skip with high-spirited hearts in the soft flowers of the meadow.

Such are those whom you honor, majestic goddess, ungrudging spirit.

Hail, mother of the gods, wife of starry Ouranos,

freely grant me a heart-pleasing livelihood in exchange for this song.

But I will remember you and another song, also.

(Homeric Hymn XXX to Earth, Mother of All, ll. 1-19)

World spirit and fantastic sea horses, woodcarving by Christine Cooper

Angier (my Mom!), ca. 1935.

Quotation for March, 2006, from Ovid's Fasti: Mars, father of Romulus and Remus |

Ruins of temple of Mars Ultor ("Mars the Avenger"), from

Rodolfo Lanciani, Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries,

1898.

Beware the Ides of March!

Beware the Ides of March! Julius Caesar was assassinated on the Ides of March (March 15), 44 B.C.

March was the third month of the Roman calendar of Caesar's time, as it is of ours. However, March was apparently the first month of the most archaic Roman calendar, which consisted of just ten months, with an unnamed period in winter between the end of the old year and the beginning of the new.

March is named for the god Mars. Most famous as the Roman god of war (identified with the Greek god Ares), Mars also had agricultural connections as protector of the fertility of the herds and fields. It is not certain which functions are the oldest. His sacred animals were the wolf and the woodpecker. The emperor Augustus built a temple to Mars Ultor ("Mars the Avenger") in the middle of his new Forum Augustum (see the picture above).

Romulus and Remus, Mars' twin sons by the Vestal Virgin Silvia

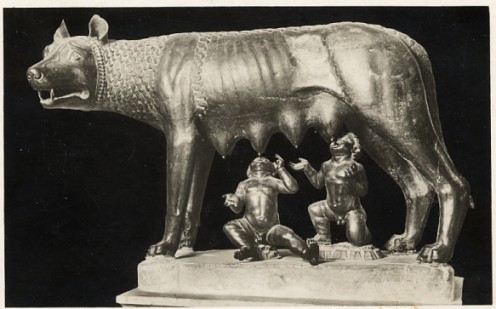

Ovid, in his Fasti, or "Roman Calendar," begins Book 3 (March) with the story of Romulus and Remus, founders of the city of Rome, who were twin sons of Mars by the Vestal Virgin Rhea Silvia. In the legend, the twins were thrown in the river by King Amulius of Alba Longa, who had deposed his brother King Numitor, father of Silvia. But they washed up on shore, where they were suckled by a she-wolf and fed by a woodpecker who brought them food. They were found and raised by a herdsman and his wife. Their identities were eventually known, and they killed Amulius and made Numitor king again. They left Alba Longa and founded their own city of Rome, where Remus insulted Romulus by leaping over Romulus' new walls, and was killed by Romulus. After a long reign, Romulus vanished mysteriously in a storm and became the god Quirinus.

Our quotation begins with Ovid's invocation of Mars and the description of Mars's stolen sexual pleasure with Silvia, whom he rapes while she sleeps, and her prophetic dream.

While the episode reads like a Playboy fantasy (and although the portraits of Vesta "covered their eyes" and the altar "trembled" when Silvia gave birth), Silvia herself appears relatively unscathed and propriety is maintained by the fact that Romulus and Remus will be the means of her father Numitor's revenge upon his brother Amulius, and will become the founders of Rome.

Warlike Mars, come near, lay aside your shield and spear for a little while,

and loose from its helmet your shining hair.

Perhaps you might ask, what has Mars to do with a poet?

From you, the month about which I sing takes its name.

You yourself see that fierce wars are waged by Minerva's hands;

is she less at leisure for the liberal arts?

After the example of Pallas, take time to put aside

your spear; you will find something to do unarmed.

Then, too, you were unarmed, when a Roman priestess

took your fancy, that you might give your great seed to this city.

Silvia the Vestal (for why not start with her?)

went at early morning for water to wash the holy objects.

She came to the sloping bank by a gentle path,

and set down the earthenware pitcher from atop her head.

Tired, she sat upon the ground, receiving the breezes upon her open

breast, and rearranged her disheveled hair.

While she was sitting, the shady willows and the singing birds

made her sleepy, as did the soft murmur of the water.

Seductive repose stole over her vanquished eyes,

and her hand, made languid, dropped from her chin.

Mars, seeing her, desired what he saw, and possessed what he desired,

but his theft went undetected, thanks to his divine powers.

Sleep left her, and she lay heavily pregnant, for already within her

womb was the founder of the Roman city.

Languid she arose, nor did she know why she arose languid,

and leaning on a tree she uttered these words:

"May it be useful and fortunate, what I just saw in a dream,

or was it too vivid for a dream?

I was present at the fires of Ilium, when from my hair

the woolen fillet fell before the sacred hearth.

Thence, wondrous to behold, two palm trees rose side by side;

of these, one was taller than the other,

and with its heavy boughs it spread a cover over the entire world

and touched the highest stars with its canopy of foliage.

Behold! my uncle was striking the trees with an axe!

I was terrified at the warning, and my heart pulsed with fear.

A woodpecker, Mars's bird, and a she-wolf fought to defend the tree trunks;

because of them, both palms were safe."

She finished speaking, and lifted the full pitcher with diminished strength;

she had filled it while she recounted her vision.

Meanwhile, as Remus grew, and Quirinus grew,

her belly swelled with the celestial burden.

. . .

Ovid, Fasti 3.1-42.

Romulus and Remus suckled by the wolf, Capitoline Museum.

Quotations for January-February 2006: Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day and Black History Month |

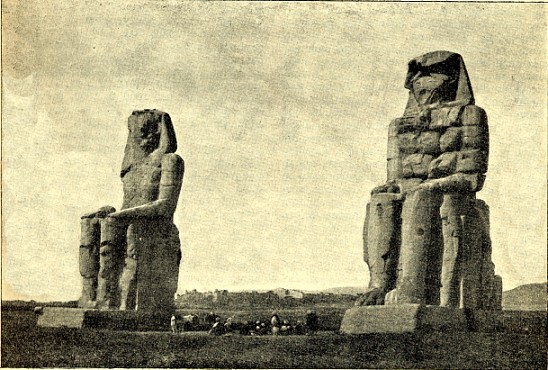

Colossal statues of Amenhotep III in Egypt, identified as the famous

"singing statues" of Memnon, King of Ethiopia, son of the Dawn goddess Eos.

(Illustration in W.H. Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der

Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1894-1897.)

The lordly Ethiopians of Homeric epic

On January 16, 2006, we observed the birthday of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and February is Black History Month. Black Africans were well known to the Greeks and Romans, and they appear in Classical literature and art both as subjects and as writers and artists themselves.

Homer knew the Ethiopians as a semi-mythical people, in whose company the gods enjoyed lavish banquets. One of these banquets is alluded to in Iliad 1.423-426. Achilles, smarting at the taking of the girl Briseis from him by his commander, the Greek King Agamemnon, begs his mother, the sea-goddess Thetis, to ask Zeus to help the Trojans, to punish Agamemnon for his lack of respect for himself, "the best of the Achaeans." Thetis replies that she will ask Zeus's help, as soon as he returns, but that he is presently away from Olympus,

for Zeus went yesterday to the Ocean, to the blameless Aethiopians,

for a banquet, and all the gods followed with him.

But on the twelfth day he will come back to Olympus,

and then I will go to Zeus's house with the bronze threshold

and, clasping his knees in prayer, I think that I can persuade him.

In Iliad 23.205-207, the funeral pyre of Patroklos fails to burn, and the messenger Iris goes to the Winds to ask them to blow to ignite the fire. She finds all the winds at the home of the West Wind, Zephyros, enjoying a feast, which they invite her to join. But she, having delivered her message, declines because of a prior engagement, saying,

"I can't sit down, for I am going back to the streams of Ocean,

to the land of the Aethiopians, where they are sacrificing hecatombs

to the immortals, that I may share in the sacrificial banquet."

In the Odyssey, too, the god Poseidon is depicted as receiving sacrifices of bulls and rams from the Ethiopians (Odyssey 1.22-25) (here we see the common confusion in the use of the name "Ethiopian" (the name means "burnt-face") to refer to dark-skinned people extending from Africa to India, as seen in Homer's reference to the Ethiopians being "divided into two, some at the setting sun, some at the rising"). On a more human plane, Menelaos, describing his own wanderings on the way home from Troy, tells of the places he visited, including Phoenicia, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Libya. On a still more personal note, Odysseus himself, still in disguise on his return to Ithaka, is describing Odysseus (really himself!), whom he claims to have "met," to the faithful Penelope. In Odyssey 19.244-248, he describes Odysseus' Black herald Eurybates (the name means "wide-stepping"):

And there was a herald, a little older than he,

round in his shoulders, of black complexion, wooly-headed;

Eurybates was his name. Odysseus honored him above his other

companions, because his thoughts were in harmony with his.

Memnon in the lost epic of the Aethiopis

An entire lost epic from the time of Homer, the Aithiopis, as well as several lost plays, were devoted to the legend of Memnon, son of the dawn goddess Eos and the the Trojan prince Tithonos. Memnon was king of Ethiopia and fought on the Trojan side in the Trojan War. He was slain by Achilles, but was made immortal by Zeus. In Egypt, he was identified with Amenhotep III (reigned ca. 1411-1375 B.C.), whose colossal statues near Thebes gave a ringing tone when they were struck by the rising sun, an event thought to be Memnon's greeting to his mother, Eos (see illustration above).

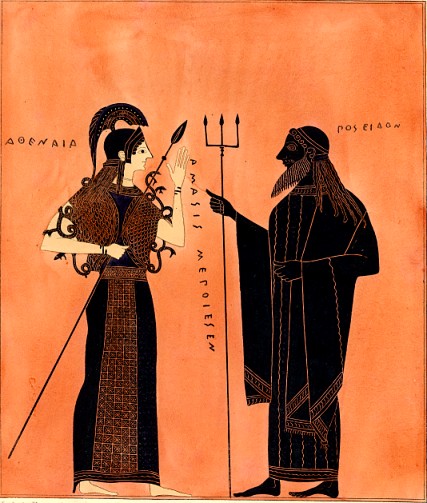

References to Africans in Classical Greek theater include, among several others, Aeschylus' Suppliants, where the fifty sons of Aegyptus are described as having black limbs that stand out from their white robes. In art, there many depictions of Negro faces and figures in vase paintings and sculptures. An outstanding potter/vase painter, Amasis (several of whose signed vases still exist -- see the illustration at the foot of this item), shared a name with an Egyptian pharoah, and, according to Prof. Frank M. Snowden, Jr. (see reference below), may well have been black African.

Vergil's dark-skinned love

At Rome, in Vergil's second Eclogue, the shepherd Corydon is pining for a boy named Alexis, the favorite of his master. Unable to win Alexis over, Corydon yet advises the boy that he can be better off (Eclogue II ll. 14-18):

Wouldn't it be better to put up with the gloomy anger of Amaryllis

and her arrogant haughtiness? Or with Menalcas,

although he is black, and although you are fair?

O beautiful boy, do not trust too much in your complexion:

white privet flowers fall, but black blueberries are gathered.

The Roman playwright Terence

The Roman playwright Terence (Publius Terentius Afer, ca. 195-159 BC.) wrote comedies of character and manners that contrasted with the more slapstick qualities of the other great Roman comic playwright, Plautus; it is Terence who gave us the line

I am a human being; I consider no human matter to be alien to me.

Terence was said to have been born at Carthage and brought to Rome as a slave. Having been educated and set free by his master, he gained entrance to Roman society, and his daughter is said to have married a Roman knight. (It should be noted that slavery in antiquity was not associated with any particular race, but with which people happened to be conquered. At Rome, where slaves might be Asians, Africans, Jews, Syrians, Greeks, Germans, Gauls, or others, slaves were often better educated than their masters, and were frequently put in charge of educating their masters' children.)

Many more references to Blacks in the ancient world can be found in Frank M. Snowden, Jr., Blacks in Antiquity, Harvard University Press, 1970.

Signed vase painting by the Athenian potter/painter Amasis (6th cent.

B.C.), depicting Athena and Poseidon. The two figures are labeled

ATHENAIA and POSEIDON. The inscription down the middle reads

AMASIS MEPOIESEN ("Amasis made me"). Amasis may well have been

African. (Illustration from a lithograph by Kaeppelin et Cie., ca. 1840.)

---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2005 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: