These are quotations for the year 2011. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2011, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2011 |

Below are quotations for the year 2011. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2011

Click on a link to read each quotation

2011

- December 2011: For the party and gift-giving season, Telemachus learns to make a graceful exit — while declining a gift he can't use (Odyssey Book 4).

- November 2011: For the Republican Presidential debates, some advice for the candidates from Cicero's De Oratore.

- October 2011: For Oktoberfest, some ancient uses of beer, among the Sumerians, Egyptians, and in Pliny's Natural History.

- September 2011: For the beginning of the school year, Athena disguised as Mentor (the eponymous "mentor") teaches Telemachus how to be a man (Odyssey, Bk. 2 vv. 267-300).

- August 2011: The evil of poetic recitations in August (Juvenal Satire III).

- July 2011: Thinking of summer vacation — Catullus' greetings to his beloved villa at Sirmio.

- June 2011: For Father's Day, Aeneas rescues his father Anchises from the burning ruins of Troy in Vergil's Aeneid.

- May 2011: The killing of Osama bin Laden and tornados in the U.S. both suggest the killing by Zeus of the monster Typhoeus in Hesiod's Theogony 820-880.

- April 2011: For Easter, Passover, and Earth Day: Persephone is reunited with her mother in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

- March 2011: Spring flowers: Persephone is lured by a magical narcissus in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

- February 2011: For Valentine's Day: a little winged Cupid described by Asclepiades of Samos.

- January 2011: Global warming and weather chaos: Phaethon's wild ride (Ovid, Metamorphoses II.161-256).

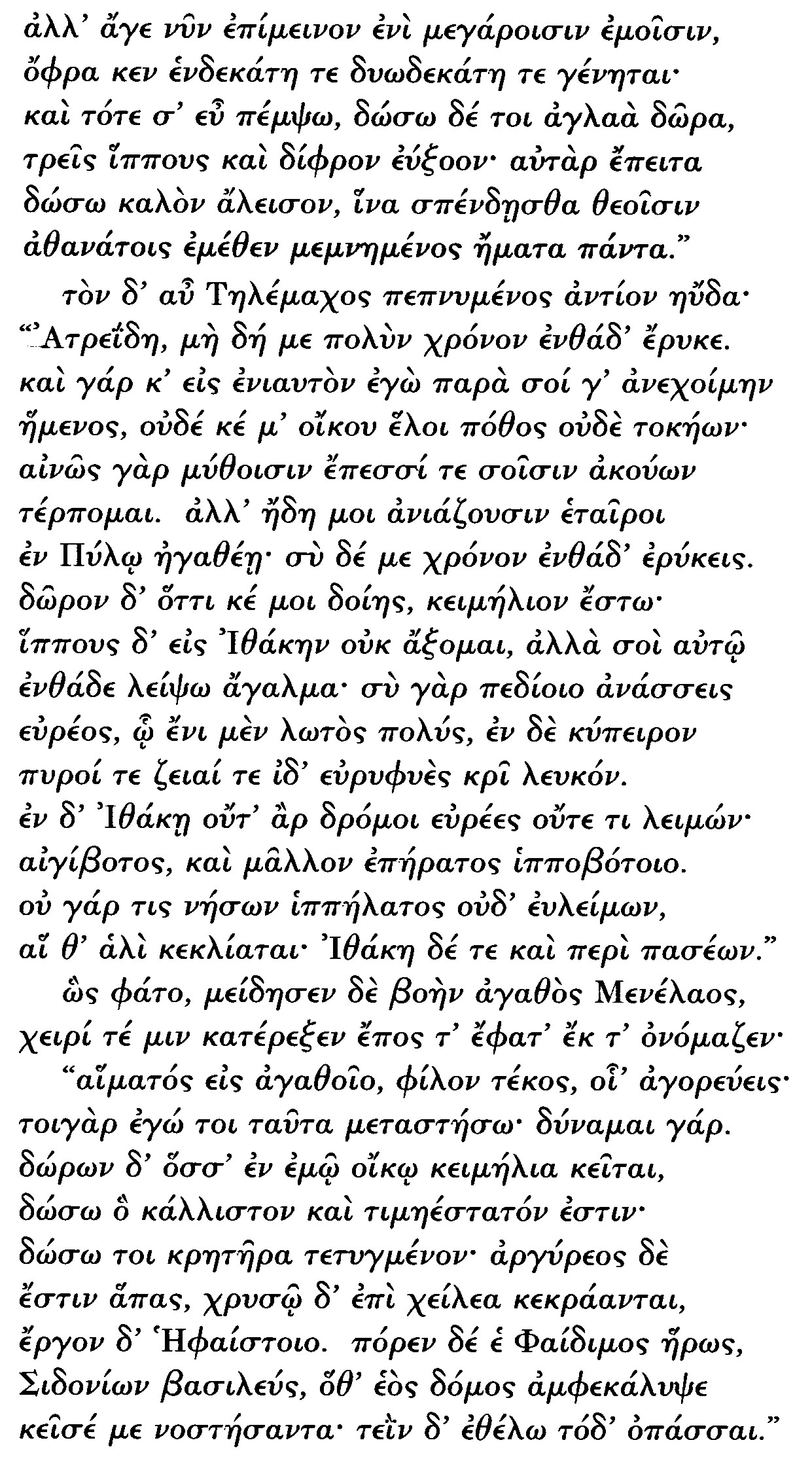

Quotation for December 2011: For the party and gift-giving season, Telemachus learns to make a graceful exit (Odyssey Book 4) |

A stele from Mycenae, depicting a horse and chariot. (Illustration from Henry Schliemann, Mycenae: A Narrative of Researches and Discoveries at Mycenae and Tiryns, 1880.)

Dear Miss Manners, how do I extricate myself from a garrulous host (and politely decline a gift I can't use)?

Most of us have been there. We've had a great visit with a wonderful storyteller, who just doesn't want to stop. "Stay a while longer, you're going to love this next story..." (Of course, the opposite also happens, when we are the host or hostess and a guest doesn't want to leave!) Likewise, we've sometimes been offered a marvellous gift, which obviously means a lot to the giver, but which we simply can't use. How do we gracefully extricate ourselves from the situation? Our Quotation of the Month, from Book 4 of the Odyssey, brings us Telemachus, searching for his father Odysseus, as he leaves from his visit to the court of Menelaus, King of Sparta.

Menelaus and the Old Man of the Sea

In the Quotation of the Month for September, Athena, in the guise of family friend and counselor Mentor, literally "mentors" young Telemachus, urging him to take a ship to search for news of his long-absent father, and to "act like a man" worthy of his father's lineage. Telemachus goes first to Pylos, where he visits King Nestor, who advises him to travel to Sparta, where King Menelaus has more recently arrived from Troy. Menelaus, now safely home with Helen, tells of his own eight-year journey home, including adventures in Phoenicia, Ethiopia, Sidon, Libya, and Egypt. In Egypt, he wrestles with the shape-changing Proteus, the Old Man of the Sea, who tells Menelaus of the murder of his brother Agamemnon by Aegisthus (the role of Agamemnon's wife Clytaemnestra is downplayed here), and of Odysseus' captivity on Calypso's island of Ogygia. Of course, at this point, Odysseus has in fact been released and is on his way home to Ithaca, where Telemachus, on his own return, will meet him in the hut of the swineherd Eumaeus (Od. 16.1-22).

An example of "re-gifting"

Menelaus is enjoying the visit, and invites Telemachus to stay a couple more weeks, and offers him a gift of a three-horse chariot, complete with horses, plus a fancy drinking goblet. Telemachus turns down the invitation, pleading that his companions, whom he left in Pylos, are waiting for him. He also declines the horses and chariot, because on Ithaca there are no flat meadows appropriate for keeping them. He tries to be diplomatic, but can't resist injecting a remark that "our goat-country is preferable to horse-country." This jibe could be motivated by Menelaus' earlier remark that he is willing to set up Odysseus, if he should return, with all his family and household in a nice little city near his own palace, after conveniently clearing it of its current inhabitants by "eminent domain"! (Od. 4.174-177). Telemachus negotiates for an exchange of his present to some "treasured heirloom" (keimelion — "a thing stored up"). Menelaus, experienced as he is, smiles and pats him, and praises his speaking style, worthy of his lineage. He then promises him one of his heirlooms, a mixing bowl made by Hephaestus, which was given to Menelaus by Phaedimus ("Glorious"), King of the Sidonians, providing us with an early example of "re-gifting"!

Telemachus returns to Ithaca, picking up his companions at Pylos, but, with apologies, goes straight to his ships, bypassing the palace of Nestor, another overenthusiastic host! (Od. 15.195-201).

HomerOdyssey, Bk. 4 vv. 587-619

|

Menelaus' generosity

"But come now, stay in my halls |

A silver and gold goblet from Mycenae. (The diagonal lump of metal on the front is not part of the cup, it was fused to it in the heat of the funeral pyre. Illustration from Henry Schliemann, Mycenae: A Narrative of Researches and Discoveries at Mycenae and Tiryns, 1880.)

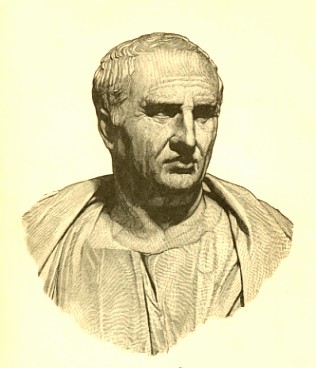

Quotation for November 2011: Advice for the presidential candidates from Cicero's De Oratore |

Marcus Tullius Cicero. His advice on oratory could well be studied by the Republican candidates for president. (Illustration from Select Orations and Letters of Cicero, 1892.)

Debaters not ready for prime time

It is the beginning of the holiday season, but also the beginning of the political season. We have been watching in appalled amusement as one after another Republican candidate for President of the United States outdoes the others in misinformation, memory lapses, and general bumbling. We have Michele Bachmann's famously misinformed statements (for example, confusing actor John Wayne with serial killer John Wayne Gacy), Herman Cain's amorous life and befuddlement about Libya, and Rick Perry's inability to remember the names of all the departments he wants to eliminate (he froze trying to remember "Energy Department" — why couldn't he just make a joke saying "The third department is so forgettable, that's why I want to eliminate it"?). Together, they show a lack of ability to think on their feet. All could take lessons from the ancients, who not only spent entire lives pursuing public speaking, but wrote copiously on rhetoric (the Greek word) and oratory (the Latin word). To help them out, this month's Quotation of the Month is an extract from Cicero's de Oratore, "On the Orator."

How to remember stuff

Cicero wrote the de Oratore in 55 B.C., during a period in which he was withdrawn from public life, devoting his leisure time to study. It is written as a dialog, as he says in a letter, "in the Aristotelian manner" (a claim that cannot be proved, since unfortunately, Aristotle's dialogs, unlike Plato's, have not survived to our day). It is set in 91 B.C., in the time of Cicero's own boyhood, and its principal participants are Licinius Crassus, whom Cicero makes the spokesman of his own opinions, and Marcus Antonius, the grandfather of the triumvir, the famous Mark Antony. Several younger men also participate. Many different aspects of public speaking are covered, including different kinds of humor (Example: When Fabius, a general, recaptured the town of Tarentum, Livius, another general, reminded him of the role his own exploits played in the capture. Says Fabius, "How could I forget? Your losing the town made my recapture possible!" — de Or. II.273.) Of more relevance to the current situation is a discussion of the art of memory and its use in public speaking. Antonius tells how the poet Simonides gave a recitation at a banquet hosted by the wealthy patron Scopas, who, after dinner, refused to pay him his full fee. Simonides received a message that someone awaited him outside. No one was there, but as Simonides left, the roof fell in, killing everyone inside. Simonides was able to identify the bodies by remembering where each had sat at the table, and from this experience developed a theory of memory, based on putting the things you want to remember in imaginary locations. By remembering the order of the locations, you remember the things to be remembered.

Antonius's anecdote appears below, in Latin and English. The "sons of Tyndareus" are the (mythical) Castor and Pollux, whose story Scopas apparently felt took up too much of Simonides' song. Were they perhaps the "two young men" who came to the door and mysteriously disappeared?

Cicero De Oratore II.86.351-354

. . . gratiamque habeo Simonidi illi Cio quem primum ferunt artem memoriae protulisse. Dicunt enim cum cenaret Crannone in Thessalia Simonides apud Scopam fortunatum hominem et nobilem cecinissetque id carmen quod in eum scripsisset, in quo multa ornandi causa poetarum more in Castorem scripta et Pollucem fuissent, nimis illum sordide Simonidi dixisse se dimidium eius ei quod pactus esset pro illo carmine daturum: reliquum a suis Tyndaridis quos aeque laudasset peteret si ei videretur. Paulo post esse ferunt nuntiatum Simonidi ut prodiret: iuvenes stare ad ianuam duos quosdam qui eum magnopere evocarent; surrexisse illum, prodisse, vidisse neminem; hoc interim spatio conclave illud ubi epularetur Scopas concidisse; ea ruina ipsum cum cognatis oppressum suis interiisse, quos cum humare vellent sui neque possent obtritos internoscere ullo modo, Simonides dicitur ex eo quod meminisset quo eorum loco quisque cubuisset demonstrator uniuscuiusque sepeliendi fuisse; hac tum re admonitus invenisse fertur ordinem esse maxime qui memoriae lumen afferret. Itaque eis qui hanc partem ingeni exercerent locos esse capiendos et ea quae memoria tenere vellent effingenda animo atque in eis locos collocanda: sic fore ut ordinem rerum locorum ordo conservaret, res autem ipsas rerum effigies notaret, atque ut locis pro cera, simulacris pro litteris uteremur.

___________________________________

. . . I am grateful to the great Simonides of Ceos, who, it is said, first invented the art of memory. For they say that when Simonides was dining in Crannon in Thessaly at the home of Scopas, a wealthy nobleman, and he sang a song he had written for him, in which, as poets do, he had included, for the sake of ornamentation, many verses about Castor and Pollux, Scopas very nastily told Simonides that he would pay only half what was contracted for the song. The rest he could ask for from his sons of Tyndareus, whom he had equally praised, if he wished. A little later, they say, a message was brought to Simonides, asking him to go outside, that there were two young men standing at the door who were earnestly asking him to come out. So he got up, went out, but saw no one. In the intervening time, the hall in which Scopas was banqueting collapsed, and Scopas himself with his relatives were buried in the ruins and died. But when their people wanted to bury them, the bodies were so crushed that one could not tell them apart by any means, but Simonides is said, because he remembered at which place each one reclined at table, to have been able to point out each for separate burial. Moved by this incident he is said to have discovered that it is order that brings the maximum illumination to memory. And so those who would exercise this part of their talent should select locations and then make images in their mind of the things they want to hold in memory and place them in those locations. Thus the result is that the order of the locations preserves the order of the things, and the images of the things note down the things themselves, and just as we use the locations as a wax writing tablet, so we use the images as the letters.

A Roman orator. (Illustration from Select Orations and Letters of Cicero, 1892.)

Quotation for October 2011: For Oktoberfest, some ancient uses of beer, among the Sumerians, Egyptians, and in Pliny's Natural History |

The Alulu Beer Receipt, an ancient record of a delivery of beer, from the Sumerian city of Ur, in modern Iraq, ca. 2500 B.C. The text is translated as "Ur-Amma acknowledges receiving from his brewer, Alulu, 5 sila [about 4 1/2 liters] of the 'best' beer." Image from Wikipedia Commons, photographby Dr Tom L. Lee.

Beer and wine among the ancients

October is time for the Oktoberfest, when we drink lots of beer. The Greeks and Romans were wine-drinkers rather than beer-drinkers. When Athena, in the guise of Mentor, counsels young Telemachus to take a ship and search for his father Odysseus, she orders the expedition to be provisioned thus:

Get ready provisions and store them all in vessels,

wine in amphoras, and barley, the marrow of men,

in close-packed skins. . . ,Odyssey 2.289-291

Even the Mycenaean Linear B tablets mention wine among various products.

Vergil spends a large part of his second Georgic on the details of vine-raising, and Pliny the Elder devotes Book 14 of his Natural History to the cultivation of different kinds of grape and the wines that are made from them.

Egyptian Paradise, Sumerian drunk-dialing

To the Egyptians and Sumerians, on the other hand, beer was an important part of the lives (and afterlives!) of both people and gods. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, we find that the Egyptian idea of Paradise involved plenty of food and beer (or as usually translated, "cakes and ale"). Perhaps the most inventive use of beer is in the Sumerian poem of Inanna and Enki. Inanna, sometimes called the Sumerian Aphrodite, gets Enki, the god of water and of wisdom, drunk on one beer after another, until he gives her all his powers (the me), which she then gives to the people of her city of Uruk. These powers include powers of kingship and priesthood, of crafts (woodworking, copper, reed-work, etc.), of kindling fire, of music, of warfare, of descent and ascent from the Underworld, of emotions, and of sexual arts, including prostitution, among many others. Her gifts thus combine those of Aphrodite, Athena, Hermes, Apollo, and Prometheus.

Give yourself a beer facial

Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, does mention beer, describing its use as a cosmetic! Then he quickly moves on to wine. Pliny, a career military man and attorney, was prodigiously inquisitive and wrote voluminously on subjects such as history, weaponry (a work on the javelin as a cavalry weapon), and education. His only surviving work is his Naturalis Historia in thirty-seven books, covering the physical universe, geography, anthropology, zoology, botany, botany in relation to pharmacology, zoology in relation to pharmacology, mineralogy and metallurgy and their use in the arts. Not a scientist himself, he depended on various prior sources. His curiosity led him to sail to get a closer view of the eruption of Vesuvius, August 29, 79 A.D., which buried Pompeii and Herculaneum. With his encyclopedic work still unfinished, he died of asphyxiation on the shore before he could escape.

In Book 22 of the Natural History, Pliny discusses the medicinal uses of grains. In this context, he mentions that the peoples of Egypt, Spain, and Gaul make a drinks from grain, and that in Gaul it is called cervesia — the modern Spanish word cerveza is "beer"! But his main point is that women use the foam from the beer to nourish their complexions. If this seems odd, consider the practice of modern women to sometimes use beer as shampoo! Below, in Latin and English, is the relevant quotation:

Pliny, Historia Naturalis 22 lxxxii 164

Ex iisdem fiunt et potus, zythum in Aegypto, caelia et cerea in Hispania, cervesia et plura genera in Gallia aliisque provinciis, quorum omnium spuma cutem feminarum in facie nutrit. Nam quod ad potum ipsum attinet, praestat ad vini transire mentionem atque a vite ordiri medicinas arborum.

From these same things [grains] drinks are also made, zythum in Egypt, caelia and cerea in Spain, cervesia and many kinds in Gaul and other provinces. Of all of these, the foam nourishes the skin on the face of women. But as for what pertains to the drink itself, it is better to go on to the mention of wine and and from the vine to describe the medicines from trees.

Vesuvius erupting, as depicted on an old postcard. Pliny the Elder died during evacuation from the eruption of Vesuvius that buried Pompeii and Herculaneum in 79 A.D.

Quotation for September 2011: For the beginning of the school year, Athena disguised as Mentor teaches Telemachus how to be a man |

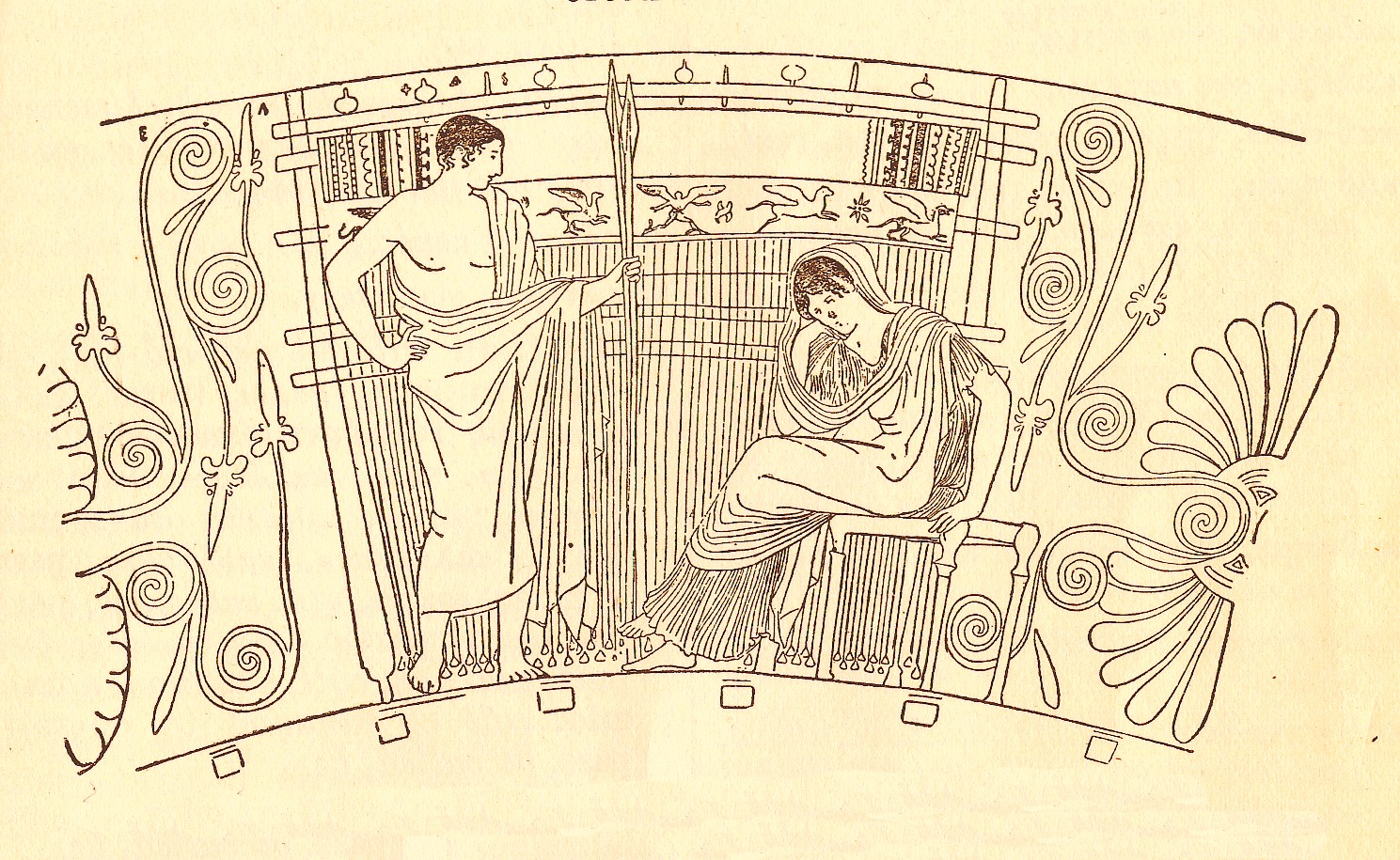

Telemachus with Penelope at her loom. Drawing based on a painting on a scyphus (drinking cup) from Chiusi, ca. 400 B.C. after Baumeister, Denkmäler, Fig. 2332, in Selections from Homer's Iliad, 1906.

The search for a role model and guide

The school year begins, and many students will be seeking a mentor, a teacher, counselor, or experienced fellow-student to help them navigate the unknown waters of a new school and the life that lies beyond. The original "mentor" was in fact man named Mentor, a character in the Odyssey, an older friend of Odysseus whom Odysseus leaves in charge of his household while he is on his twenty-year-long journey to Troy and back. More importantly, Athena, assuming the guise of Mentor, guides Telemachus, Odysseus' son, on his own journey to find his father, teaching him to be a man.

Telemachus' journey

The Odyssey is the story of Odysseus' wanderings and homecoming after the fall of Troy. But it is also the story of Odysseus' son Telemachus, a Bildungsroman that traces his transformation from a hesitant and insecure youth into an assured adult who takes his place as a "man of the house" alongside his father. This story occupies most of Books I-IV of the Odyssey and is sometimes called the "Telemacheia."

Athena assumes the guise of family friends Mentes and Mentor

The Odyssey opens with the famous words introducing Odysseus,

Andra moi ennepe, Mousa, polutropos, hos mala polla

plagchthê, epei Troiês hieron ptoliethron epersen

Tell me, Muse of the man of many ways, who wandered much,

after he had destroyed the sacred citadel of Troy.

The poet tells of Odysseus' seven-year imprisonment on Calypso's isle of Ogygia, but quickly shifts to a council of the gods, at which it is decided that Hermes shall go to Ogygia and tell Calypso to free Odysseus, and that Athena shall go to Odysseus' home in Ithaca and "put courage (menos) in the heart of his son." She must get Telemachus to call an assembly of the Ithacans, including the greedy Suitors who are wooing his mother, and "put them on notice" apeipomen), then she should tell Telemachus to go to Pylos and Sparta to seek word of his father. The scene shifts to the palace of Odysseus, where the Suitors are eating and drinking all of Odysseus' food and wine, and playing checkers (or draughts, (Od.1.107); see illustration below). Penelope's ruse of weaving by day and tearing out her work by night has been discovered, the pressure is on her to marry someone before all Odysseus' stores are depleted, and, as we find out later, Odysseus himself had said if he did not return, Penelope should remarry when Telemachus began to grow a beard (Od. 18.259-270). Telemachus is unhappy, but feels helpless, still very much the child. Athena takes charge, in the guise of family friends Mentes and Mentor.

Mentes, the trader

Athena arrives first as the mysterious stranger, Mentes, who identifies himself as a friend of his father, a trader in iron and copper. "Mentes" counsels him to call an assembly and order to Suitors to go home, then to travel to Pylos and Sparta to seek word of his father from Nestor and Menelaus. If his father is dead, he should plan how to kill the Suitors, then send his mother back to her father to find a suitable husband. He should use Orestes' killing of Aegisthus, who slew his father Agamemmnon, as an example. "Put aside childish things, since you are no longer of that age" (Od.1.297). "Mentes" does not stay, he is just passing through — then "he" (really Athena) flies off like a bird, revealing her divine nature. Mentes is just "passing through" the narrative as well, being a double (we could say a "warm-up act") for the similarly-named Mentor, who appears next. Penelope is amazed at her son's new take-charge attitude (he orders her to her room when she objects to Phemius' sad song of the return of the Greeks from Troy).

Mentor, the Ithacan elder

Athena next takes the form of Mentor, whom we first meet as a real person standing up in the assembly and berating the Ithacans for allowing the Suitors to get away with their outrageous behavior. Telemachus, leaving the brief gathering after arguing with the Suitors, goes to the seashore and prays to the god who visited him the previous day, who then appears as Mentor. "Mentor" reinforces "Mentes'" advice, and not only offers to find him a ship, but promises to go with him. When they arrive at Nestor's palace, Telemachus does not know what to say, inexperienced as he is. Athena truly "mentors" him, telling him that some things he will know he wants to say, for the rest the god will prompt him (Od.3.25-28). He just has to be himself. Telemachus and Athena are gone for quite a while in Pylos and Sparta, getting news of the fates of the Greek heroes, and the owner of the ship they have borrowed inquires when they are expected to return, because he needs his ship back for his mule-raising business. By his inquiry, he inadvertently tips off the Suitors, who did not know he was gone, and who now set a trap for him (Od.4.632-640). The shipowner is also puzzled that he saw "Mentor" getting on the ship, but later saw him on land! Was it a god? As the story is picked up later in the Odyssey, Athena, realizing Telemachus' danger, alerts him to return not to the palace, but to the hut of Eumaeus the swineherd, where, unbeknownst to Telemachus, the disguised Odysseus has now already arrived (Od.15.36-39).

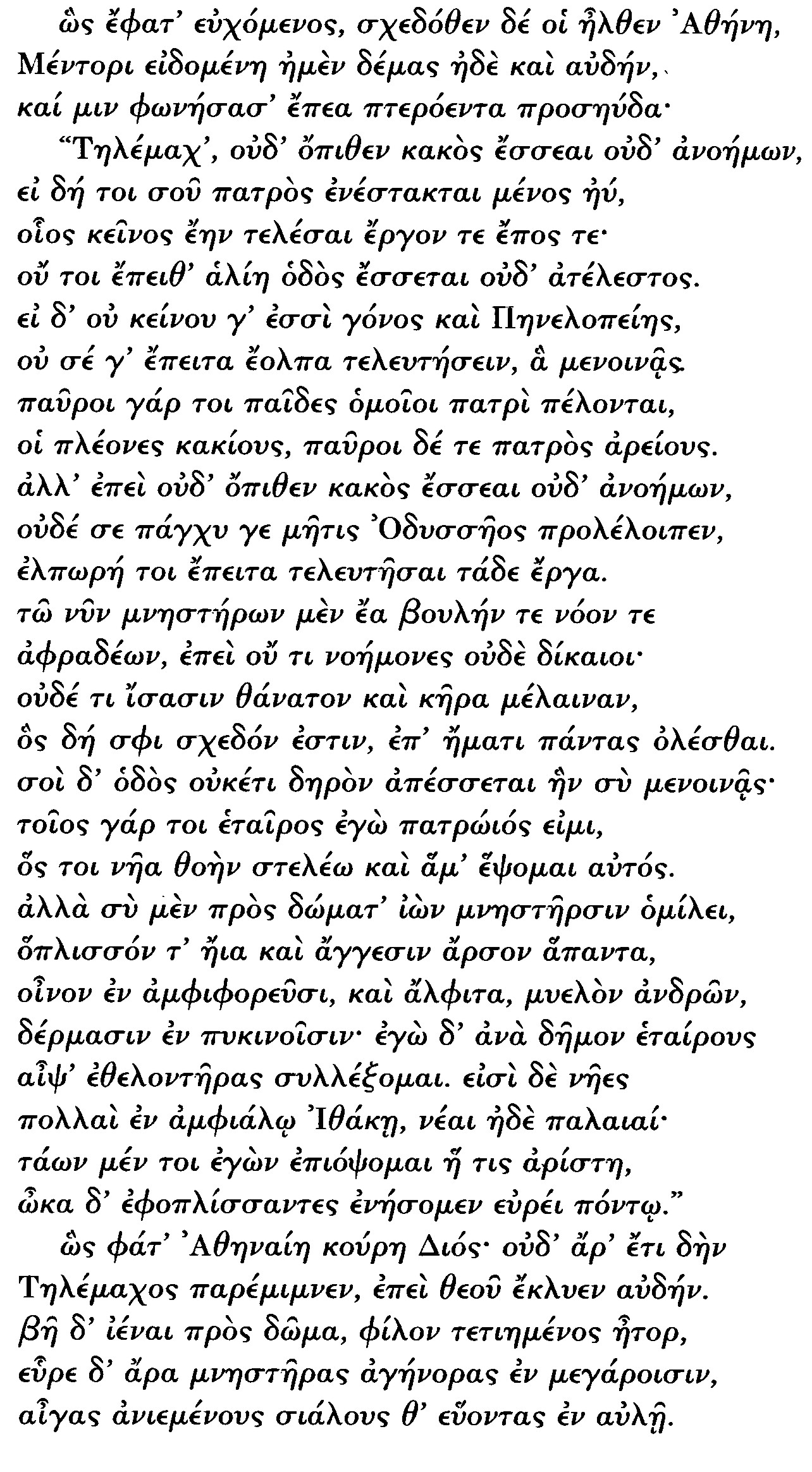

Below, in Greek and English, is Mentor's advice to Telemachus when he comes to him on the seashore.

Illustration: An Egyptian game of draughts, used in Autenrieth's Homeric Dictionary, 1876, to illustrate the word pessoisi in the description of the Suitors' game.

HomerOdyssey, Bk. 2 vv. 267-300

|

Learn to be a man, TelemachusThus he spoke in prayer, and Athena came near to him, |

Reconstruction of the megaron or Great Room of Odysseus' palace. Illustration, "combined from different ancient representations," from Autenrieth's Homeric Dictionary, 1876.

Quotation for August 2011: The evil of poetic recitations in August (Juvenal Satire III) |

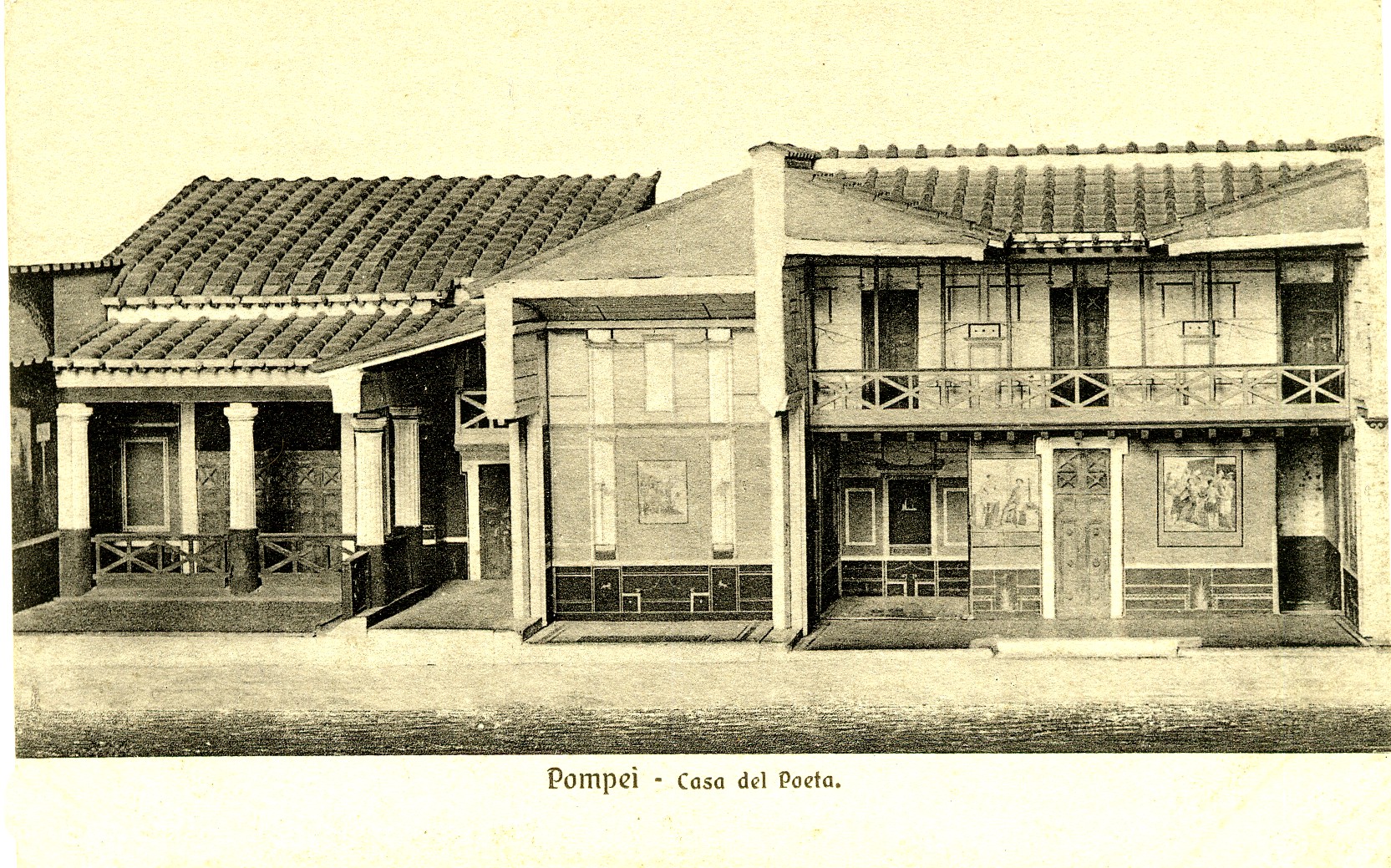

The House of the Tragic Poet at Pompeii, so called from its mosaic of a poet rehearsing the cast for a theatrical scene. In this reconstructed view, the right-hand portion is cut away, revealing paintings on the walls. (From an old postcard.)

Rome in August: time to leave town!

August in Rome was the worst month. The sweltering heat, the noise, the fires, and the malarial epidemics drove everyone who could afford it to leave for the countryside. To these evils, Juvenal, in his Third Satire, adds another: having to listen to public recitations of bad poetry! The custom of poets giving readings of their new poems before publication was instituted by Asinius Pollio (consul 40 B.C., a patron of Vergil and Horace), as a means of stimulating interest in writing and to provide feedback to the authors. Juvenal had already made clear his detestation of windy poetic readings (not just in August). In Satire I, he explains his reasons for writing verse himeslf. He is sick and tired of listening to other poets' recitations, and never being able to get even. These satiric verses are his revenge.

Immigrants and celebrity-chasers are ruining the old Roman virtues!

The Third Satire is presented as Juvenal's farewell to his friend Umbricius, who is leaving Rome for the country, apparently forever. Most of the poem consists in Umbricius' explanation for his leaving. It is one long rant (later adapted in English by Samuel Johnson in his satirical poem "London") complaining of the influx of dishonest foreigners (especially Greek!), the high cost of living (driven up by the necessity to impress the rich and powerful), and the decline of old Roman values (complaints which sound eerily like today's conservative laments!).

Juvenal (55?-140? A.D.) was probably born in the reign of Nero and suffered through the reigns of several more emperors, dying, perhaps, at a remote military post in Egypt, where he may have been banished by Hadrian, as a result of some insulting verses about one of the emperor's favorite actors. He may have held some official posts, and taken up writing late in his career, but little is actually known of his life. He writes as if he had first-hand knowledge of some of the degradations and deprivations of which he writes.

The rich man's house is opulently rebuilt, the poor man loses his home

We quoted from the Third Satire in another Quotation of the Month, for September 2005, after Hurricane Katrina, when President Bush boasted that Senator Trent Lott's house, swept away in the flood, would be rebuilt as a "fantastic house," even as thousands drowned and suffered in the streets of New Orleans. In Rome, too, the humble Codrus, whose house burned down, "lost all that nothing that he owned," while the rich man's friends rush to rebuild his house more opulently than before.

The opening verses of Satire III follow below in Latin and English. Prochyta (modern Procida) was a small island off the coast near Naples, the Subura a famously crowded, noisy, and poor area of Rome.

JuvenalSatura III, vv. 1-9 Quamvis digressu veteris confusus amici,laudo tamen, vacuis quod sedem figere Cumis destinet atque unum civem donare Sibyllae. ianua Baiarum est et gratum litus amoeni secessus. Ego vel Prochytam praepono Suburae; nam quid tam miserum, tam solum vidimus, ut non deterius credas horrere incendia, lapsus tectorum adsiduos ac mille pericula saevae urbis et Augusto recitantes mense poetas? . . . |

I don't blame you for leaving Rome!Although troubled at the departure of my old friend,I praise him nevertheless, for his determination to fix his abode at empty Cumae, and to give one citizen to the Sibyl. It is the gateway to Baiae and a pleasant shore for a lovely retreat. I myself prefer even Prochyta to the Subura. For what have we seen so miserable, so lonely, that you would not think it worse to tremble in fear of fires, the continual collapse of buildings, a thousand perils of the savage city, and poets reciting in the month of August? . . . |

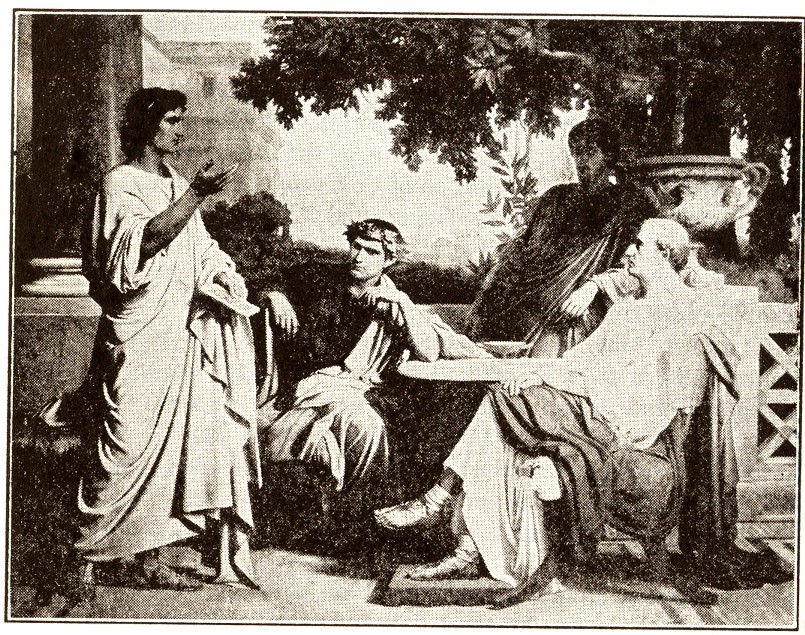

Horace, at the home of his patron Maecenas, reciting a poem to Vergil, Varius, and Maecenas, in a painting in the Luxembourg Gallery in Paris, as rendered in an old textbook of Horace.This is a highly romanticized vision of the poet. For what is probably a more realistic depiction, see the painting of Augustus, Maecenas, and Horace found at the Palace of Augustus on the Palatine, with which we illustrated Horace's Journey to Brundisium in August 2007, with a very nerdy-looking Horace on the right.

Quotation for July 2011: Thinking of summer vacation — Catullus' greetings to his beloved villa at Sirmio |

Part of the so-called "Grotte di Catullo" at Sirmio. Traditionally identified as Catullus' actual villa, these ruins more likely are those of a Roman spa or villa of the first century A.D. (Image from Wikipedia Commons.)

Vacation on our mind

Vacation is on our minds. Either we are on vacation, are thinking about going on vacation, or wish we were on vacation. Or perhaps we have had enough of vacation and are happy to be home. For all these thoughts, we have chosen for our Quotation of the Month Catullus' Poem 31, a heartfelt greeting to his beloved lakeside villa at Sirmio, written in 56 B.C. on his return from a year on the staff of Memmius, governor of Bithynia.

Catullus had finally broken up with the woman he called "Lesbia" (after the poetess Sappho of Lesbos — she certainly wasn't a "lesbian" in our sense!) — to whom he addressed the famous words Vivamus, mea Lesbia, atque amemus "Let us live, my Lesbia, and let us love!" (Poem 5). She was really the infamous Clodia, sister of the even more infamous Clodius, enemy of Cicero. In a complete break from his life at Rome, he traveled to Bithynia, on the Black Sea in present-day Turkey. It was on this trip that he visited the grave of his brother near Troy — Atque in perpetuum, frater, ave atque vale "And forever, brother, hail and farewell" (Poem 101). Upon his return, he seems to have gone straight to his "country house" in Sirmio, before eventually returning to the social life of Rome.

Sirmio (modern Sirmione) is a long, thin peninsula sticking up from the south shore of Lake Garda, dividing the lower part of the lake in two. The Lago di Garda (ancient Lacus Benacus) is a long lake, possibly of glacial origin, in the north of Italy near Verona (Catullus' birthplace). The river Mincio (Vergil's Mincius "with banks woven with a border of tender reeds" tenera praetexit harundine ripas — Eclogues 7. 12, Georgics 3.15) flows from it past Mantua, near where Vergil was born. The northern end of the lake is lined with rocky crags. In 1851 the old Ponale Road was drilled through tunnels in the rock face to gain access to the villages in the upper end of the lake (see picture below). This old road is now used for mountain biking, and there are some hair-raising You-Tube videos of bike rides on its cliff-hanging hairpin turns. The southern end of the lake, pierced by Sirmio's peninsula, is more gentle, but the ruins on the peninsula, known as the Grotte di Catullo, seen in the picture above, are likely to be of a later era than the poet.

Below, in Latin and English, is Catullus' poem (the text is that of the Oxford edition, which differs from some other editions in reading gaudente, not gaudete in line 13). The play on words paene insularum and insularum reminds us that a "peninsula" is really an "almost island!"

Catullus Carmen 31Paene insularum, Sirmio, insularumqueocelle, quascumque in liquentibus stagnis marique uasto fert uterque Neptunus, quam te libenter quanque laetus inuiso, uix mi ipse credens Thuniamatque Bithunos liquisse campos et uidere te in tuto. o quid solutis est beatius curis, cum mens onus reponit, ac peregrino labore fessi uenimus larem ad nostrum, desideratoque acquiescimus lecto? hoc est quod unum est pro laboribus tantis. salue, o uenusta Sirmio, atque ero gaude gaudente, uosque, o Lydiae lacus undae, ridete quidquid est domi cachinnorum. |

Lovely Sirmio! (Catullus 31)Sirmio, delight of peninsulas and of islands,of all that each Neptune bears in the liquid marshes and the vast sea, how gladly and how joyful I behold you, scarcely myself believing that I have left Thynia and the Bithynian plains and see you in safety! O what is more blessed than release from cares, when the mind puts away its burden, and exhausted from foreign labor we come to our home-god and rest in our longed-for bed? This alone is reward for such great labors. Greetings, o lovely Sirmio, and rejoice in your master's rejoicing, and you too, waves of the Lydian lake, smile upon all the laughter that is in the house. |

The old Ponale Road (la Strada del Ponale) along the rocky north shore of Lake Garda, from an old postcard. Today the road is open only for mountain biking. The best way now to get to towns along the lake is by car ferry or, more expensively, by hydrofoil.

Quotation for June 2011: For Father's Day, Aeneas rescues his

father Anchises from the burning ruins of Troy in Vergil's Aeneid

|

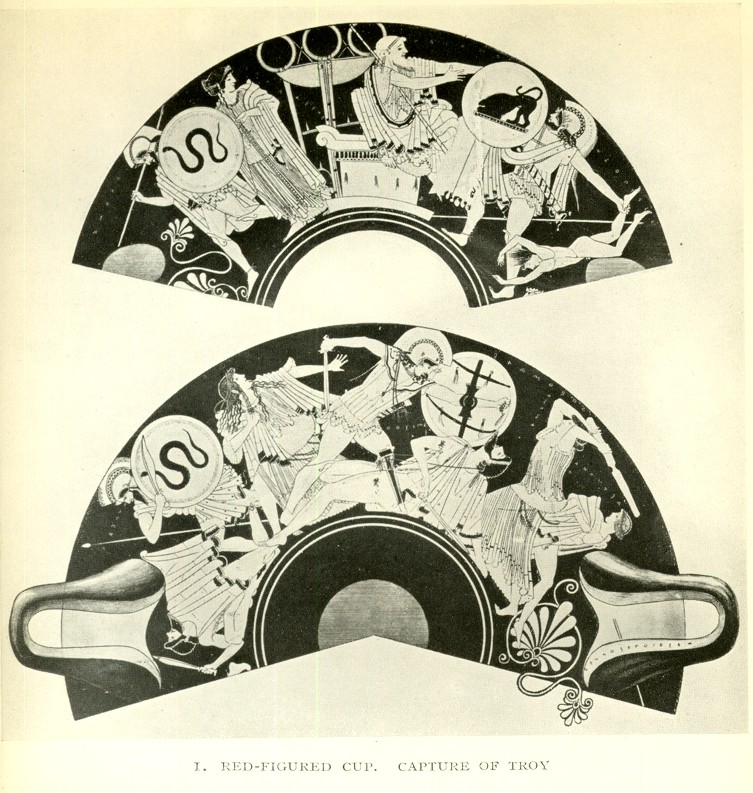

"Aeneas carrying Anchises" by Charles-André van Loo, 1729, Louvre (from Wikipedia Commons). For a different "take" on the capture of Troy, see the red-figured cup depicted below.

Anchises as a young man and as an old man

In June, we celebrated Father's Day (June 19) and our Quotation of the Month is Vergil's description of Aeneas' rescue of his aged father, Anchises, from the burning ruins of Troy. It is illustrated rather garishly by the rococo painting above, by Charles-André van Loo. It is difficult to relate van Loo's heroic nonsense to what we know of the ancient Mediterranean city of Troy, but it is perhaps even more difficult to relate the frail but still courageous old man (he wants to stay and die fighting) to the beautiful young prince Anchises of the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite — "in form resembling the immortal gods" (demas athanatoisin eoikôs), with whom the goddess Aphrodite fell madly in love. Venus, too, is now a mighty but fond presence, stage-managing her son's career, no longer the giddy Aphrodite, whom Zeus punishes for making the world fall in love by making her fall in love with Anchises. Young Aphrodite is embarrassed but proud that she is pregnant with Aeneas. Yet she presciently foretells Anchises' sad old age. She does not give him the immortality that would leave him in eternal pain and senility, like Eos' love, Tithonus.

The fog of war

Vergil is masterful in his description in Book 2, not just of the carnage of war, but its chaos. Perhaps the truest illustration of the scene would be some of the wartime footage we see on TV. In the Iliad, the Greeks are the "good guys," In the Aeneid they are the bad guys. The Trojan Horse has entered Troy, disgorging Ulysses (Odysseus) and the other Greeks. Sad old Priam, the Trojan king, is butchered at the altar by a bloodthirsty Pyrrhus (also called Neoptolemus), son of Achilles. Parents are killed in the presence of their children, children killed before their parents, families are separated, desperately searching for each other. Aeneas sets off with Anchises on his shoulders, holding his son Iulus (also called Ascanius) by the hand, with his wife Creusa following. In the confusion, Creusa is separated from the others and is never seen again alive. (We could cynically say that to make the story come out, she has to die, "thrown under the bus" so that Aeneas can later have a romance with Dido in Carthage, and still later, marry Lavinia in Italy!) Creusa's ghost appears to Aeneas (in a scene modeled on Odysseus' meeting with his mother in the Underworld), telling him he must forge on.

Below, in translation, is the scene in which a series of omens — a flame on Iulus' head, a thunderclap, and a shooting star — persuades the family that it is time to leave, and which describes their confused departure.

Aeneas carries Anchises on his shoulders (

Aeneid 2.679-740)Crying out [Creusa] filled the entire house with her laments,

When a miracle arose, sudden and wonderful to tell.

For, held between the hands and faces of his grieving parents,

a delicate point was seen to pour its light from the top

of Iulus' head, and a flame, harmless to the touch, to lick

at his soft hair and graze about his temples.

We, terrified, hurried about from fear and beat at the blazing hair

and tried to extinguish the sacred fire with water.

But father Anchises lifted his eyes joyfully to the stars,

and stretched out his hands and voice to heaven:

"Jupiter omnipotent, if you are swayed by any prayers,

look upon us — just this — and, if by our dutiful conduct we deserve it,

then give us help, Father, and confirm these omens."

Hardly had the old man spoken, when with a sudden crash

it thundered on the left, and sliding down from heaven

a star raced, drawing its torch with great light across the shadows.

We watched it, as it slid over the ridgepole of the house,

hide its bright self in the woods of Ida

marking its path; then along its long boundary its furrow

gave light, and the area wide about smoked with sulphur.

Truly convinced by this, my father rose up facing the breezes

and addressed the gods and worshipped the holy star. "Now! Now! No more delay! I follow, and where you lead, I am there,

ancestral gods. Guard our household, guard my grandson.

Yours is this augury, by your divine will, Troy exists.

I consent indeed, nor, my son, do I refuse to go as your companion."

He had spoken. Already throughout the city walls a brighter fire

was heard, and the fires roll their tide nearer.

"Therefore come, dear father, place yourself on my neck,

I will get under you with my shoulders, nor will that labor be a burden to me,

however things fall out, there will be one danger in common,

one salvation for both of us. Little Iulus

will accompany me, and at a distance my wife will follow my footsteps.

You, servants, pay attention to what I shall say.

As you leave the city there is a mound and an olden temple

of lonely Ceres, and near it an ancient cypress,

preserved for many years by the worship of our fathers.

To this one place we will arrive by different ways.

You, my parent, take in your hand the sacred things and the ancestral Penates.

For me, coming from so much war and recent slaughter,

to handle them would be sacrilegious, until I wash in the living stream."

Saying this, I spread upon my broad shoulders and stooping neck

the hide of a tawny lion as a covering,

and I submitted to my load. Little Iulus

twined himself about my right hand, and followed his father, though with steps not his equal.

Behind, his wife followed. We went onward through shadowy places,

and as for me, whom just a while ago no weapons thrown at me could budge,

not even the Greeks arrayed in their facing battle line,

now every breeze terrified me, every sound aroused me,

in suspense and fearing equally for my companion and for my burden.

And now I was approaching the gates, and seemed

to have made the entire road of escape, when suddenly a multitudinous

sound of feet seemed to reach our ears, and my parent, looking out

through the shadows, exclaimed "Son! Flee, son, they are approaching!

I see their flashing shields and glittering arms."

Then, as I became afraid, some unfriendly spirit

snatched away my confused mind. For as I followed pathless ways

in my running, and left the territory of known roads,

alas, in my misery! My wife Creusa, snatched away by fate,

did she halt? Did she stray from the path or, exhausted, sit down?

It is uncertain. After that, she never returned before our eyes.

HOW THE GREEKS THEMSELVES SAW THE TROJAN WAR

The Trojan War, depicted on a vase of the 5th century B.C. This is both more stylized and more brutally realistic than the rococo confection at the head of this article. This picture is reproduced from Rostovtzeff A History of the Ancient World, Vol. I, The Orient and Greece, 1927. Here is Rostovtzeff's description:RED-FIGURED CUP painted by Brygos. The pictures represent the capture of Troy by the Greeks with all its horrors. On one side we see Priam taking refuge at the altar of Apollo, and Neoptolemos, the son of Achilles, using the boy Astyanax to brain him with. On the other side a wild fight is going on. The heroic woman who defends her boy is Andromache. Attic work of about 480 B.C. Paris Louvre. After Furtwängler-Reichhold.

Quotation for May 2011: Ridding the world of a monstrous enemy: Zeus kills Typhoeus in Hesiod's Theogony |

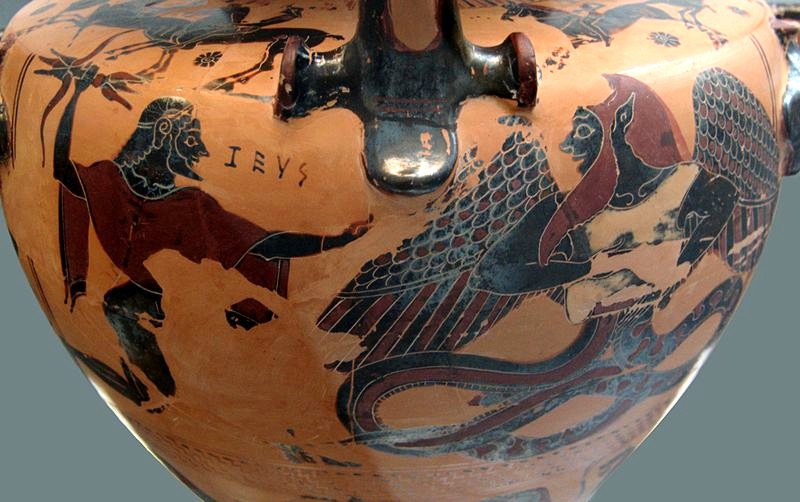

Zeus slaying Typhon (Typhoeus) with his thunderbolt. Chalcidian black-figured hydria, ca. 550 B.C., Staatliche Antikensammlungen, Munich. (Photo by Bibi Saint-Pol, from Wikipedia Commons.)

A man becomes a myth

At the beginning of the month, the big news was the killing of Osama bin Laden, whose terrorist organization Al Qaeda came to notice horrifically with the destruction on September 11, 2001 of the World Trade Center in New York. Although bin Laden was eventually found living in a villa in Pakistan, his whereabouts, and even his existence, were largely unknown for ten years. Was he living in a cave? Was he dead? Was his constant stream of taunting videos created by an impostor? The man who was killed turned out to be an aging, if busy, fanatic, dyeing his gray beard black and taking "herbal Viagra," sending out e-mails (via courier) and watching videos of himself. Somebody in the house was also watching pornography. But in those ten years, he became a mythic figure, both to his followers and to the world he terrorized, larger than life, existing nowhere and everywhere. Therefore, it seemed that the most appropriate Classical quotation would be the defeat of an ultimate demon, the monster Typhoeus, who set out to destroy the world, but was subdued by Zeus's thunderbolt and sent down to Tartarus.

As the month draws to a close, our news is dominated by tragic storms and tornados, first in Alabama, then in Joplin, Missouri, and the story of Typhoeus takes on another meaning. For it is from Typhoeus, now in the Underworld, that violent storms arise, random winds and waterspouts causing destruction to ships at sea and destroying crops, homes, and inhabitants on land.

Zeus dispatches Typhoeus to the nether regions of Tartarus

In Hesiod's Theogony, Typhoeus (elsewhere called Typhaon or Typhon) is the snake-like last wild child of Earth (Gaia), born after Zeus's climactic battle with the Titans, who were also children of Earth, and included Zeus's own father, Kronos. There are other versions, and some speculate that the story has Near Eastern origins. In the Homeric Hymn to Apollo (vv. 305-355), it was Hera who bore Typhaon in revenge for Zeus giving birth to Athena without her. In Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound (vv. 353-374) Typhon is imprisoned beneath Mount Aetna, whence "rivers of fire will burst forth." It has been thought by some that the Typhoeus episode in the Theogony, coming after the apparently final battle with the Titans, is a later addition to the poem. But it is the habit of the oral poet to add more episodes, especially if the audience is enjoying the performance. In the same way Hollywood keeps churning out sequels to its movies once it has a winning franchise!

This month's Quotation (Theogony 820-880) describes Typhoeus' birth, his hideous appearance, his ability to mimic divine and animal voices, and his attempt to take over the world. It tells of Zeus's battle with him and his ultimate fate in Tartarus, whence he continues even now to send destructive winds and hurricanes. Note that Tartarus here is both a person who mates with Gaia and a place in the Underworld. Note, too, that Hesiod's monster has human feet and hands and a hundred serpent heads, whereas in artistic representations like that illustrated above, he had a human head and winged shoulders, attached to a lower body of snakes. We also learn something about early metal-working. Earth, burning in the conflict, melts "as iron melts in the divine ground' — apparently smelted in open pits.

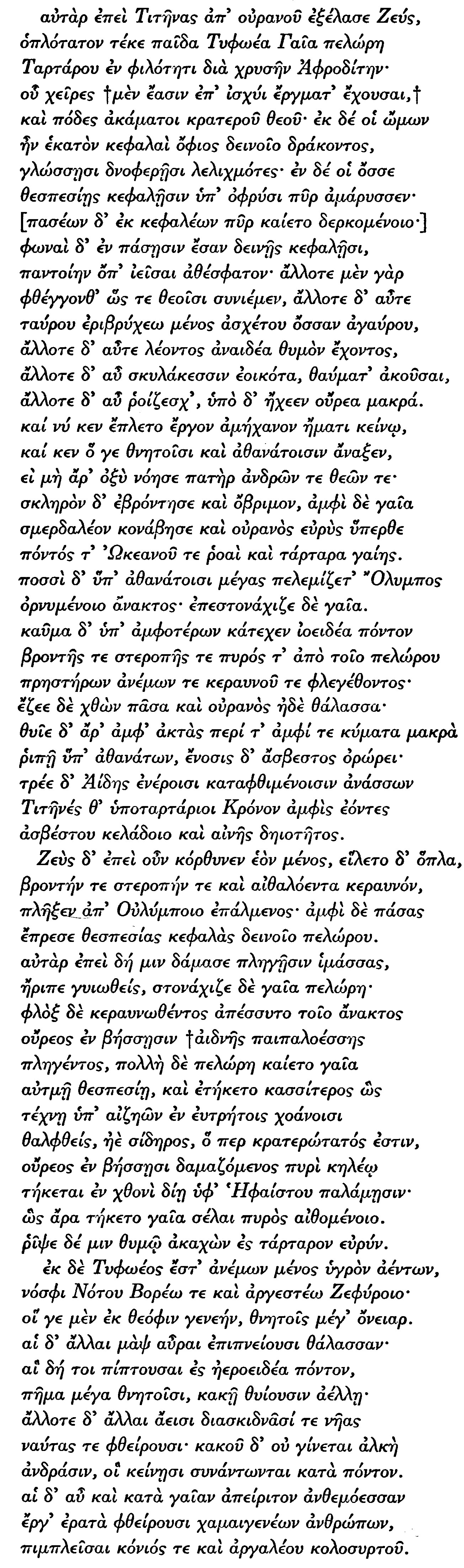

Hesiod Theogony 820-880

|

Zeus slays Typhoeus, but his tornados remainBut when Zeus had driven the Titans from heaven,huge Earth bore her youngest child Typhoeus, by the love of Tartarus, through the means of golden Aphrodite. His hands were strong in all his works, and the feet of the mighty god were tireless. From his shoulders came a hundred heads of a snake, a terrible serpent, flicking their dark tongues, and from the eyes beneath the brows in their wondrous heads fire gleamed. Fire flashed from all his heads as he stared. There were voices in all his terrible heads uttering all kinds of unspeakable sounds. At one time, they made sounds such as the gods understand, but at another time the voice of a bellowing bull, ungovernable in fury, at another time again that of a lion reckless in his anger, at another time, though, sounding like young dogs, a wonder to hear. At another time, though, he would hiss, and the high mountains echoed. Truly an irremediable event would have happened on that day and he would have ruled over mortals and immortals if the father of men and gods had not quickly noticed. He thundered hard and mightily, and the earth around resounded terribly, and so did the wide heaven above and the streams of Ocean and Earth's regions of Tartarus. Great Olympus shook beneath the immortal feet of the king as he arose. The earth groaned in reply. The heat from both seized upon the violet-hued sea — from the thunder and lightning and from the monster's fire, from the tornado winds and the blazing thunderbolt. The entire land boiled, and so did the heaven and the sea. The long waves raged around and about the headlands from the rushing about of the immortals, and an unstoppable shaking arose. Hades was afraid, ruling over the dead below, and so were the Titans below Tartarus who live with Kronos, because of the unstoppable clamor and the terrible strife. When Zeus heaped up his strength and seized his weapons, thunder and lightning and smoking thunderbolt, springing from Olympus he struck Typhoeus. Around him he burned all the wondrous heads of the terrible monster. But when he had subdued him, flogging him with blows, he threw him down, wounded, and the huge earth groaned. Flame shot out of the thunderstricken lord in the craggy ravines of the dark mountain as he was struck. The huge earth was broadly burned by the awful breath and melted like tin when heated by strong men in well-pierced crucibles, or like iron, which is the strongest of all, when, subdued by burning fire in mountain ravines, it melts in the divine ground by the hand of Hephaistos. Thus indeed the earth melted by the flash of the burning fire. Grieving in his heart Zeus cast him into broad Tartarus. From Typhoeus come strong winds that blow humidly, except Notus and Boreas, and clear Zephyr — their origin is from the gods, a boon to mortals. But these other winds blow randomly upon the sea. Some, falling upon the murky main, are a great calamity for mortals, raging with evil storms. At different times they blow in different ways; they scatter ships and destroy the sailors. No defense against the evil comes to men who meet these upon the sea. Other winds, upon the boundless flowering earth, destroy the lovely works of earth-born men filling them with dust and painful tumult. |

Bronze statue of Zeus found in the sea at Artemisium. The right hand formerly held a thunderbolt. (c. 460 B.C.). The statue has been thought by some to be of Poseidon, holding a trident, but this view is largely rejected. (Image from An Outline History of Art, 1938.)

Quotation for April 2011: For Easter, Passover, and Earth Day: Persephone is reunited with her mother in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter |

Students of the American School celebrate Easter with the family of Themistocles, one of our workmen, in Corinth. I (in my student days) am facing the camera, second from right. Lambs are roasting in a pit dug in the street. The next day being St. George's Day, we all went up craggy Acrocorinth and joined the celebration at the chapel of St. George. (Date: 1964.)

A celebration of life

This month we celebrate Easter (both Western and Orthodox), Passover, and Earth Day, all celebrations of life and the triumph of life over death, when the earth becomes green after the rigors of winter and living things that lay dormant rise from the loosened soil. (Only the skiers will be unhappy!) For our quotation of the month, we conclude our two-part story of Persephone's abduction to the Underworld and her return from it, followed by Demeter's imparting of the Eleusinian Mysteries to her worshipers, as told in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter.

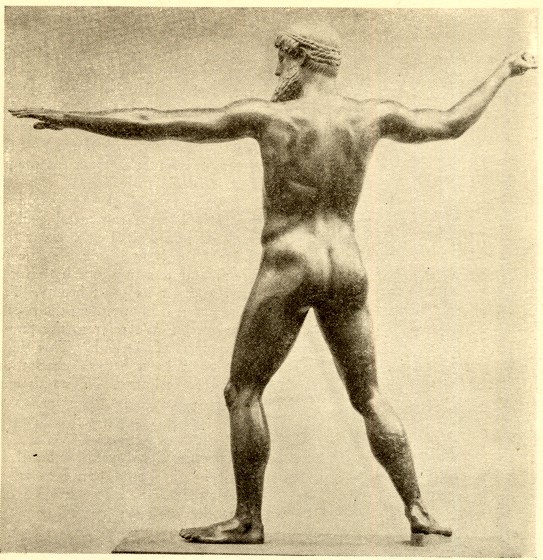

Queen of the Underworld

In Homer, Persephone is the dread Queen of the Underworld, reigning with her husband Hades, the King of the Dead, to whose dank, nightmarish home Odysseus travels in his own Journey to the Underworld in Book 11 of the Odyssey. But once, as the Hymn to Demeter tells us, Persephone was a young maiden, picking flowers in a meadow. As we saw in the Quotation for March, Hades (Persephone's uncle!) kidnaps her, with the collusion of her father Zeus, and takes her to the Underworld — a story told (in terms perhaps familiar to the poet's audience) of a father marrying off his daughter to a wealthy older man (Plouton, "The Wealth-Giver")! Demeter, mourning for her daughter, disguises herself as an old woman, and becomes nursemaid to the young Eleusinian prince Demophon, whom she tries to make immortal by putting him in the fire. Discovered in the act by Demophon's horrified mother Metaneira, Demeter reveals herself in all her towering divinity, promises fame to Demophon, but commands the Eleusinians to build her a temple (which they do), and promises to teach them her rites. End of story? Not yet! Demeter sulks in her brand new temple, and causes a failure of the grain crop, of which she is the goddess, and famine, which threatens all mankind. Only when Zeus orders Hermes to tell Hades to let Persephone go and Persephone returns, does Demeter let the lush grain grow, and she finally teaches her promised Mysteries to the people of Eleusis. But before Persephone leaves, Hades surreptiously feeds her a pomegranate seed, to ensure her return to the Underworld. (Thematic Alert! this is the motif of The Meal in the House of the Dead. To partake of food in anyone's home is to ensure the guest's return visit. For an analysis of more themes in this Hymn, see my book Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns.) In the Hymn, Hades is almost apologetic, telling Persephone that she shouldn't feel so sad, he will really be a good husband, and that she will have great honors, and the right to punish those who disrespect her!

Persephone's backstory

In the selection below, Hades agrees to let Persephone rejoin her mother, but slips her the pomegranate seed. On her arrival, Demeter rejoices, but asks if she ate anything (in the lines that follow our quotation, Persephone does tell exactly what happened). Demeter explains that if she partook of anything, she must return to the Underworld for one third of the year, but will spend two thirds above ground with her mother and the other gods. (Unfortunately, the manuscript containing this part of the Hymn is damaged, and some words have been filled in by later scholars, as indicated by brackets in the quotation below). And that is how it happened: Persephone arrives with the spring, when flowers bloom in the meadows, where other maidens will pick them, as she did once, long, long ago...

The Hymn to Demeter is described as an "aetiological myth," explaining the origin (aitia) of the Eleusinian Mysteries. It also explains how Persephone became Queen of the Underworld. In modern parlance, we would call this "Persephone's Backstory."

In the picture at the bottom of this selection, Persephone has her arm draped companiably around Hades' shoulders. Maybe marriage to her wealthy old uncle wasn't so bad after all. Cerberus isn't the terrifying guard dog of the Underworld here, but more like a family pet, with each of his three heads begging for doggy treats, or perhaps a walk!

Hymn II to Demeter 357-403

|

Persephone is reunited with her motherThus Hermes spoke, and Aïdoneus, lord of those below, smiled |

Persephone with her torch, Hades with his staff, and three-headed old guard dog Cerberus: Just a comfortable family with their eager pet! (Illustration from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

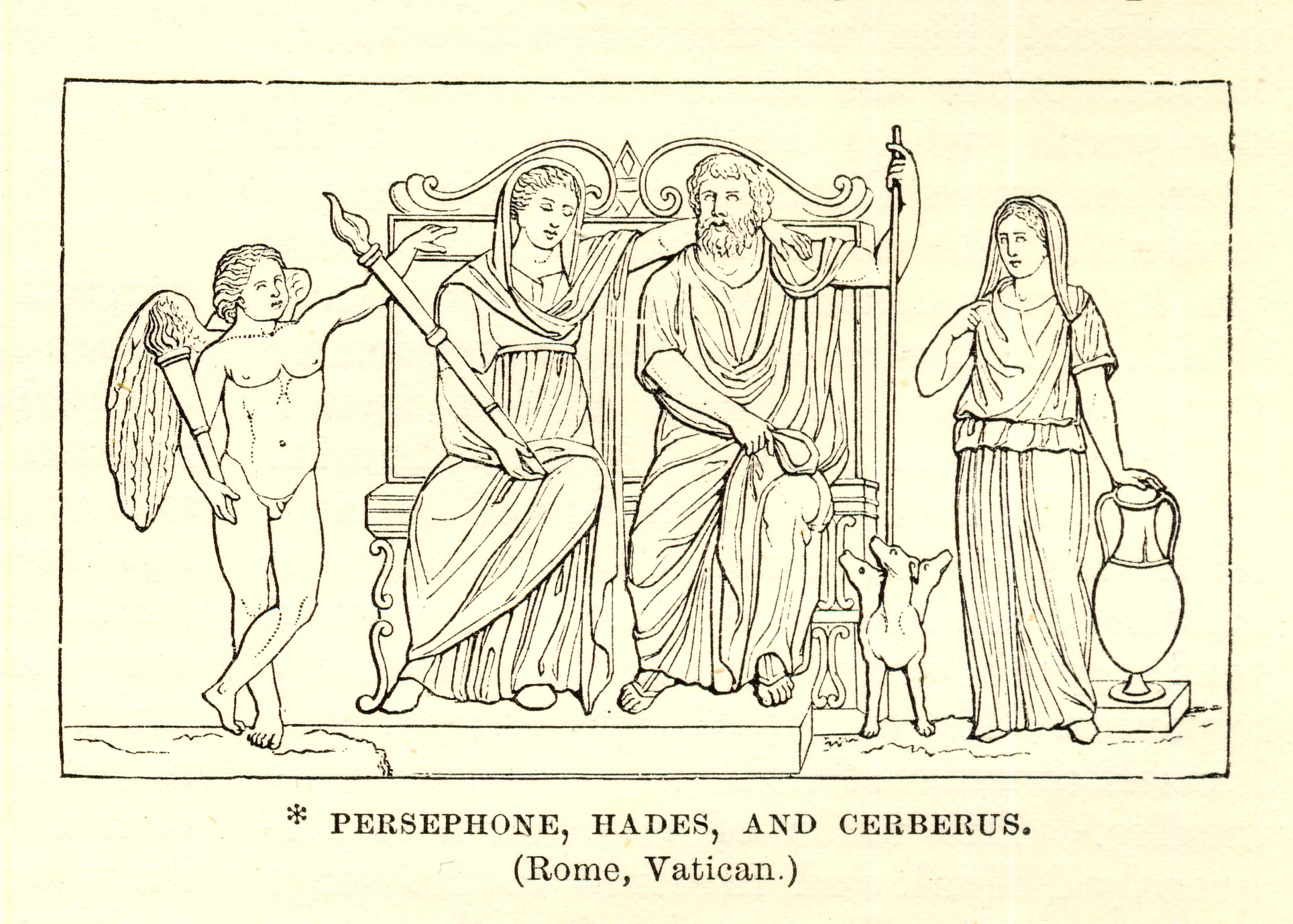

Quotation for March 2011: Spring flowers are in bloom, and Persephone is lured by a magical narcissus in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter |

Flowers bloom in a field near the Marathon Mound, while a goat nibbles on a the branches of a tree.

The crocus and narcissus are in bloom

The spring flowers are coming up all over the place. In my garden, they follow an inexorable order. First is the winter aconite, which blooms even when there is snow on the ground, then the crocus, followed by the daffodil, then the violets, and finally the rose appears. Right now, the daffodils are coming out. The daffodil, which comes in many varieties, some with single heads, others with multiple blooms, is also called the narcissus, and under this name it is a magical and mythical flower. One of the best-known myths about the narcissus is about the beautiful youth named Narcissus (the original narcissist!) who fell in love with his own reflection, pined away, and was turned into the eponymous flower. But it was also a magical, miraculous hundred-headed narcissus that Hades used to lure Demeter's daughter Persephone when he seized her and carried her off to the Underworld.

The narcissus was associated with Demeter, especially in her chthonic, or Underworld associations, perhaps in her original identity as a double for Gaia. (A supposed origin of the word from narkê "numbness" may be simply a folk-etymology.) The narcissus was also sacred to the Eumenides (the "gracious goddesses" or Furies).

This month's quotation consists of the beginning lines of Homeric Hymn II to Demeter, describing Hades' seizure of Persephone as she and her comrades play in a field of flowers. This is the traditional mythic theme of the Maiden Abducted While Dancing and Picking Flowers, just one of the mythic themes woven together in this complicated story. The scene sets in motion the long tale of Demeter's search for her daughter, her disguise as a nursemaid to young prince Demophon, her epiphany as a goddess and subsequent erection of a temple to her at Eleusis, the famine she causes as she continues to mourn, and her eventual reunion with Persephone — but only for part of the year, because Persephone ate of the pomegranate secretly given her by Hades. (These and other themes are analyzed in my Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns, of which selected chapters are available on this Web site.) In Persephone's world, roses, crocuses, violets, hyacinths, and narcissus are all in bloom at once!

When Persephone cries out for her father, Zeus, only Hecate and Helios hear her. Helios, the Sun, of course, sees everything. Hecate is an old chthonian goddess, associated with the Underworld, a goddess of women and of the crossroads. Zeus does not hear her; he is sitting in his temple, receiving offerings from mortals. Things are going according to his plan. Once again, the overbearing father has, without asking anyone else, given his young daughter to a wealthy older man (in this case, his own brother Hades, here called Aidoneus, who, incidentally, is sometimes known by the name "Plouton," "the Wealth Giver")! Below are the opening lines of the poem.

Hymn II to Demeter 1-27

|

Persephone is lured by a flower

I begin to sing of lovely-haired Demeter, revered goddess, |

The daffodils in this picture look quite harmless, but the magical narcissus by which Persephone was lured into Hades' arms was a wonder to behold.

Quotation for February 2011: For Valentine's Day: a little winged Cupid described by Asclepiades of Samos |

Capturing the spirit of the Greek Anthology

I wish I knew who doodled the charming pictures that illustrate this month's Quotation of the Month. A former artist/owner of my used copy of F.A. Wright's The Poets of the Greek Anthology (1924) filled its pages with watercolor illustrations, some tiny, some full page, of Classical and mediaeval subjects. Of the two chosen here, the first depicts perhaps a river god and a nymph, the second illustrates the old rumor that the poetess Sappho flung herself off a cliff for love. Whoever that owner was, he or she had fun. This month's Quotation is as short as the previous Quotation (Phaethon's clueless ride across the sky) was long, a four-line epigram in elegiac meter by the Alexandrian poet Asclepiades. Although this poem is one of those discussed and translated by Wright, I have not used his rhyming translation, but have used my own.

A garland of flowers in verse

When we speak of the "Greek Anthology" we generally mean the great Palatine Anthology, a collection of epigrams, short poems, dedications, epitaphs, and such from Classical and Byzantine times gathered by Cephalas in the 10th century A.D., whose only manuscript was rediscovered in 1606 in the count Palatine's library in Heidelberg. The Anthology of Cephalas (the word "Anthology" means "a gathering of flowers") drew on earlier Anthologies, starting with the earliest, the Garland of Meleager (c. 90 B.C.). The subjects of the poems of the Anthology vary from the witty to the serious, from Christian to pagan, from heterosexual to homosexual. There are many poems by the epigrammatist Asclepiades, mostly on love.

Love gets his baby wings

Asclepiades (fl. 270) was an accomplished poet of the Alexandrian period, an older contemporary of Theocritus. He was an innovator in erotic poetry, and seems to have been an early depictor of Eros, Love, as a winged infant, not the slim young man of earlier art. We see this new baby Eros in the epigram included below, in which he comes to rest in the home of a beloved woman named Danis.

Asclepiades (Greek Anthology XII.105)

|

An infant Cupid flies to a new home

A tiny Love, still easily caught, though I have flown away from my mother, |

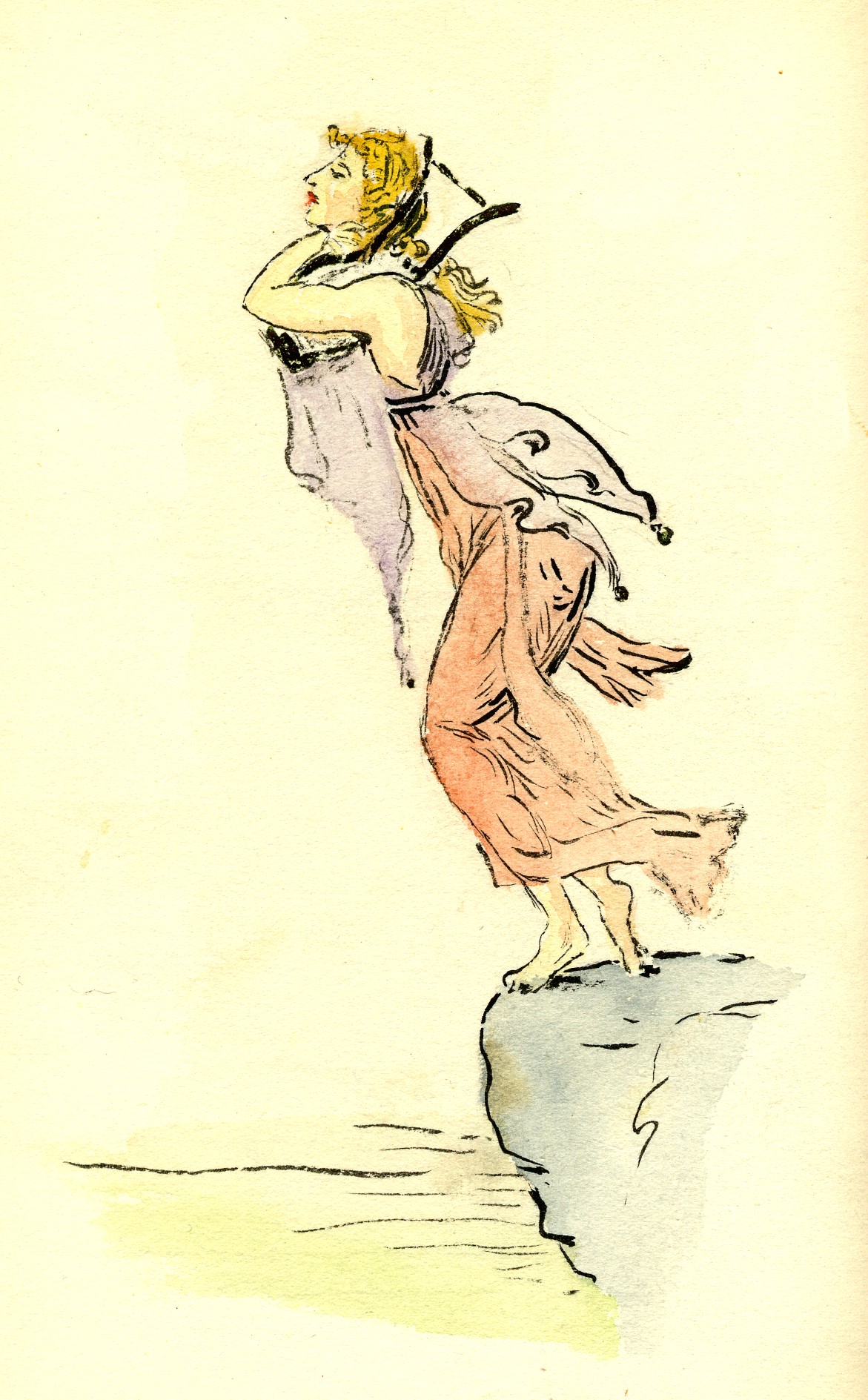

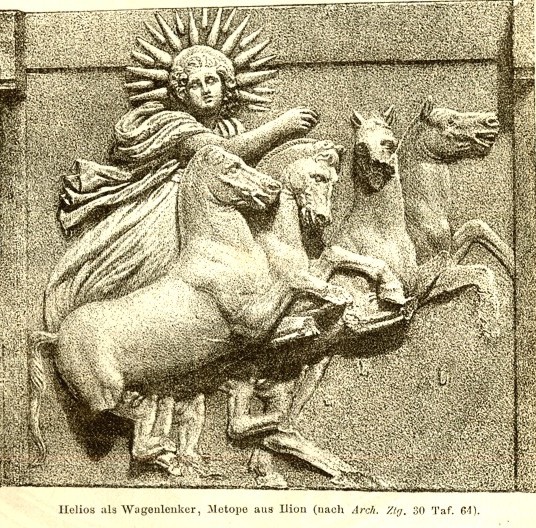

Quotation for January 2011 (and the beginning of February): Global warming and weather chaos: Phaethon's wild ride (Ovid, Metamorphoses II.161-256) |

Helios in his chariot. Phaethon tried to drive his father's team, not even knowing the horses' names (for the record, they were named Pyrois, Eous, Aethon, and Phlegon). (Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890).

Global warming and crazy weather

My apologies for missing the deadline for the January Quotation (it is now February), but I have been shovelling snow, and shovelling snow, and shovelling snow...

Worldwide, the weather has gone insane. Floods in the Indus Valley, Brazil, and Australia, drought and fires outside Moscow, end-to end blizzards in the Northeastern U.S., several inches of unaccustomed snow in the American South, glaciers melting and drying up everywhere. Scientific consensus ascribes this meteorological mayhem to global warming, which makes the ocean currents and jet stream career wildly off track. What ancient myth most accurately describes the situation? Why, Phaethon, of course. Phaethon, foolishly attempting to drive the chariot of his father Helios the Sun, across the sky, not knowing how to drive, how to handle the horses, or even knowing the way, zooms up and down, as the Earth burns and sizzles beneath him, like a scared kid going 150 mph behind the wheel of his father's Maserati.

Phaethon's mad ride

As Ovid tells the story in the second book of the Metamorphoses, Phaethon (Greek for "Shining One"), son of Clymene, wife of Merops, king of Ethiopia, discovers that his true father is the Sun God (Latin Sol or Phoebus, Greek Helios). Phaethon asks his father to grant him proof that he is truly his father, and Phoebus promises to grant whatever his son asks. Phaethon asks to drive his father's sun-chariot for a day, and Phoebus immediately regrets his promise. (Such promises always turn out badly. Remember Semele — she asked that Zeus, father of her unborn son Dionysos, come to her in his true shape. He does, as a thunderbolt that kills her; Dionysos is later born from Zeus's thigh.) Unable to dissuade Phaethon, Phoebus at least gives him detailed directions: Both the ascent into the sky and the descent from it are steep; the heavens swirl around in constant motion; avoid the celestial monsters, the Lion, the Scorpion, Crab, the Serpent, and others; take a path that does not go straight, but slantwise in an arc; don't go too high (or you will burn up the sky) or too low (or you will burn up the earth). Jupiter himself, he says, for all his power, can't drive this chariot. But Phaethon isn't listening. He takes off, and the horses, Pyrois ("Fire"), Eous ("Dawn"), Aethon ("Blaze"), and Phlegon ("Flame"), immediately recognize an amateur at the reins (he has not even learned their names). The chariot wallows around, and when Phaethon, frightened by the menacing Scorpion, drops the reins, the horses charge all over the place, bumping into stars (incursant stellis) and setting the Earth and its cities on fire as the rivers and seas dry up. The Nile hides his head in fear, "and it is still hidden" (quod adhuc latet). It is then, too, that the Ethiopians become black.

Jupiter runs out of rain

Earth, in agony, appeals to Jupiter to put out the fires, but there are no clouds or rain, for they have all dried up. Finally, Jupiter kills Phaethon with a thunderbolt, and the horses break free, abandoning the wrecked chariot. Phoebus, in mourning, goes into eclipse for a day, leaving the burning Earth to cast — fortunately! — the only light (let Jupiter drive the chariot, he says, at least while he's driving he can't kill other fathers' sons with his thunderbolt!). Phaethon's sisters, the Heliades, weeping incessantly, become trees (in their confusion, they do not understand why their feet can no longer move, and twigs grow from their bodies as bark closes over their faces; when their mother tries to remove the twigs, they bleed, and she has to stop — this is, after all, the Metamorphoses, and Ovid always thinks about weird details). Their tears become amber, "to be worn by Roman brides" (nuribus...gestanda Latinis). It is when Jupiter goes around inspecting the damage that he sees (and makes love to) Callisto, the nymph who was turned into a bear and then into a constellation, the subject of December's Quotation of the Month.

Ovid's story is spun out to baroque lengths (over 400 verses), but we quote the part that describes Phaethon's clueless ride. The Triones, or "Ox-Cart," are also known as the constellations of the Great Bear and the Lesser Bear. Ovid gets ahead of himself here, for the story of Callisto and her son Arcas being turned into constellations and the prohibition against their bathing in the Ocean is made to follow the story of Phaethon in the Metamorphoses. Oeagrius was the father of Orpheus, who was torn to pieces on Mount Haemus in Thrace. Hence, "Haemus, not yet Oeagrian." We pick up the story where the horses realize that the chariot "feels different":

Ovid, Metamorphoses Book II vv. 161-256

... |

Phaethon loses control

... |

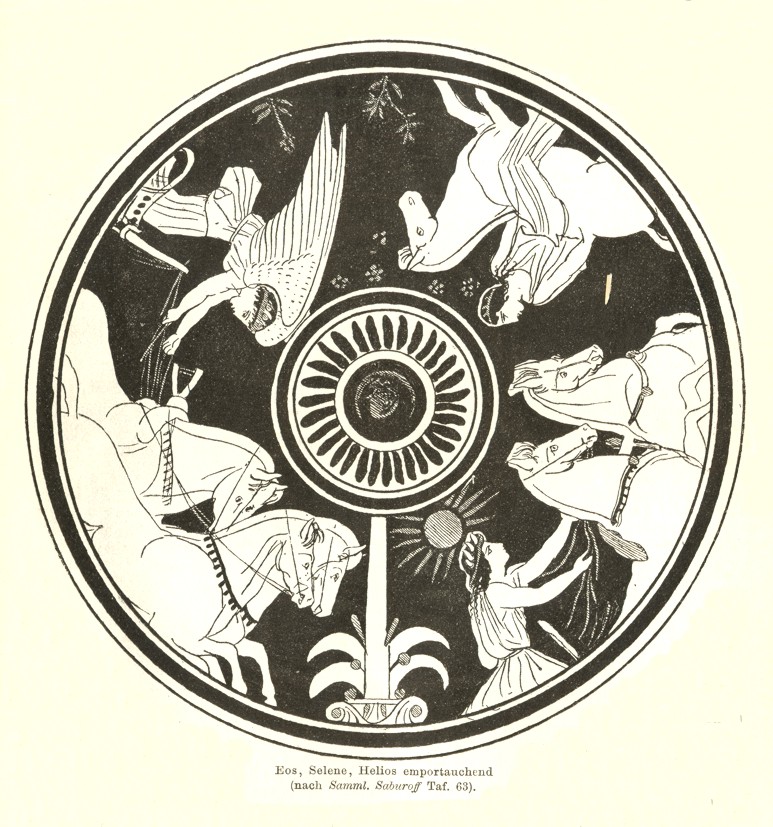

Rising and setting of Eos (Dawn), Selene (Moon), and Helios (Sun). (Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

<---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2010 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: