These are quotations for the year 2008. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

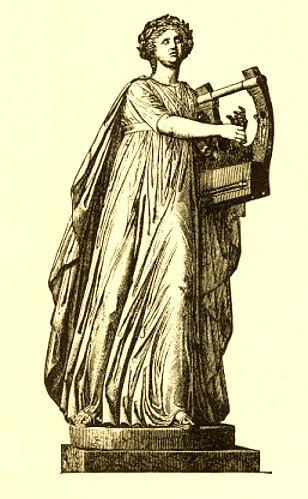

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2008, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2008 |

Below are quotations for the year 2008. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2008

Click on a link to read each quotation

2008

- December 2008: The poet Horace tells us that when it is snowing outside we should stay in and party.

- November 2008: For Thanksgiving: The poet Catullus dedicates a dependable old boat that is to be retired, in thanks for a safe voyage.

- October 2008: For non-participants in the fall sports events, The philosopher Seneca salutes the unathletic nerd.

- August-September 2008: A review of the movie WALL-E, a robot love story, and a quotation from Homer's Iliad.

- July '08 To honor the birth of a daughter to a man in Oregon, we celebrate the seer Teiresias, who turned into a woman, then back into a man, as told in Ovid's Metamorphoses

- June '08 for the summer solstice, a tipsy celebrant looks at the heavens in Ovid's Fasti.

- May '08: Inflation, Roman style: Janus complains of the devaluation of the old currency in Ovid's Fasti.

- April '08: Suggested by the accursed Red Sox T-shirt buried under Yankee Stadium, a poem by Horace calling down shipwreck on a rival.

- March '08 For the"March Madness" basketball championships, Nausicaa and her maidens play ball in the Odyssey

- February '08 For Valentines' Day, a love poem by Sappho: the poetess "falls to pieces" (à la Patsy Cline) when she sees the object of her desire.

- January '08 Women warriors in Herodotus, suggested by the candidates in the U.S. presidential election, featuring Artemisia's valor at Salamis.

Quotation for December 2008: The poet Horace tells us that when it is snowing outside, we should stay in and party |

Horace looks out at the snow on nearby hills and decides to stay indoors and have some fun. (Illustration from an edition of Horace.)

The Winter Solstice is here. The days become cold and short, and the winds are howling. What to do? The Roman poet Horace contemplates the snow-covered peak of Mount Soracte (the modern Monte Soratte or Monte Sant' Oreste, about 20 miles north of Rome, across the valley from his Sabine villa), and decides to stay inside and party. Put more logs on the fire, open a jar of good wine, and forget about tomorrow. Or, if you are young, take your lover down to the public square, find a cozy corner, and make out.

Here, in both Latin and English is Horace's Ode, Book I, No. 9:

Vides ut alta stet niue candidum |

See how Soracte stands glittering with deep snow, |

"Hebe prepared upon the spot

A jug of purl made piping hot,

Of which she gave each God a sup;

Who sup and blow, and blow and sup."(Illustration: a comic look at a banquet of the gods, from A Burlesque Translation of Homer, London, 1797.)

Quotation for November 2008, for Thanksgiving: The poet Catullus dedicates a dependable old boat that is to be retired, in thanks for a safe voyage |

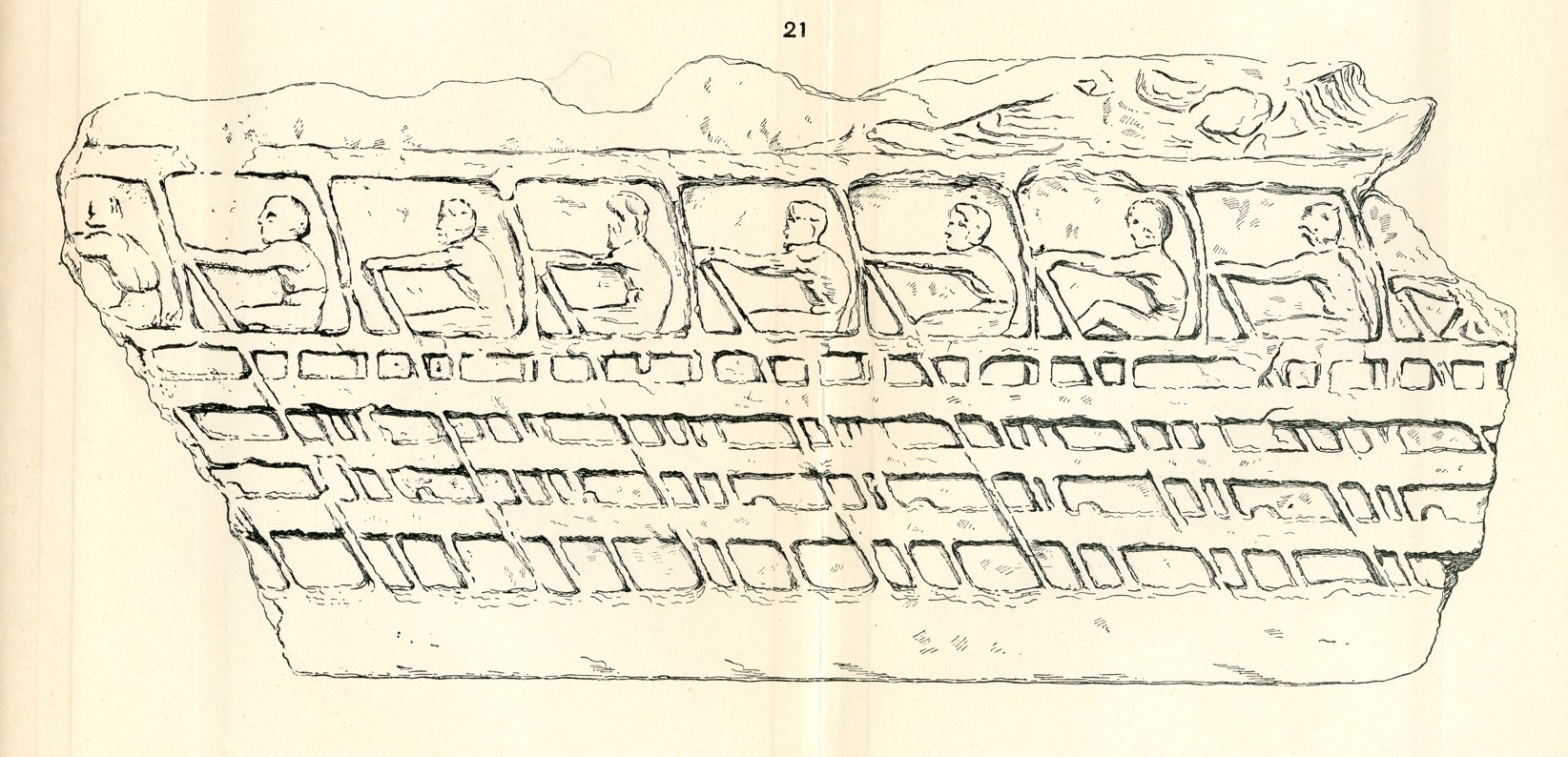

Illustration: Man sailing a corbita, a small merchant vessel (the name means "basket," probably from its shape), marble relief, ca. 200 A.D., found at Utica, near Carthage, in the British Museum. Image from Wikipedia Commons.

Catullus dedicates a retired ship to the gods

As our Thanksgiving offering, we present a poem by the Roman poet Catullus in which he dedicates a little ship, now resting in retirement, as an offering to the gods in thanks -- both to the gods and to it -- for a safe voyage home from Bithynia on the Black (or "Pontic") Sea. Catullus had served there on the staff of the governor, Memmius, returning in 56 B.C. The ship, a fast phaselus, is described as telling her own story of her birth and exploits.

A phaselus was a slender, fast passenger boat, apparently shaped like a string bean (Greek pháselos, kidney bean). This type of vessel came in different sizes, from small river-going cargo boats to large sea-going ships that could, when necessary, be used as men-of-war. They mostly used their sails, but also used oars, when necessary.

There is some question whether Catullus actually towed his little ship up the Po and Mincio rivers to his beloved home at Sirmio, or whether his offering consisted of a model of the ship. Perhaps we will never know, but it is the ship herself who speaks. (For more on the phaselus and on ancient ships in general, see Lionel Casson, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.)

Here, in both Latin and English, is Catullus' evocation of his little ship:

Phaselus ille, quem videtis, hospites, |

That boat, which you see, guests, |

Illustration: Merchant ship, about 500 B.C, from a painted vase found at Vulci in Etruria, in the British Museum. From Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895.

Quotation for October 2008: The philosopher Seneca salutes the unathletic nerd |

Illustration: A foot race, depicted on a Panathenaic amphora in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

It is better to exercise the mind than the body

We are just finishing baseball's World Series, the New York Marathon is about to take place, and the college and professional footbal season is underway. But out-of-shape nerds and couch potatoes can take heart from the words of the philosopher Seneca, who, in a letter to his friend Lucilius, expresses the view that it is more valuable to exercise the mind than the body.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 B.C.(?)-65 A.D.) was born in Córdoba, Spain, to a family of the equestrian class, but moved to Rome as a child. His father (also named Lucius Annaeus Seneca) was a well-known rhetorician, some of whose controversiae and suasoriae survive. Seneca the Younger followed the usual political career of an upper class Roman gentleman, but was more attracted to philosophy. He became tutor to the future emperor Nero, and later an influential advisor to Nero when he acceded to the throne. But Nero fell under the influence of more malevolent advisors, and Seneca was implicated in a tenuous charge of complicity in the conspriacy of Piso, and was forced, first to retire, then finally to commit suicide.

Seneca's Epistulae Morales, addressed to Lucilius, date from the end of his life, when he was living in forced retirement. These letters, which are really little essays, cover many aspects of contemporary Roman life. In his writings, Seneca was a practioner of the "pointed" style, with short, pithy, aphoristic sentences, as opposed to the resounding amplitude of the Ciceronian periodic manner. His philosophy belongs to the Stoic school, but is Roman in its emphasis on practical applications of philosophy rather than its theoretical beliefs.

In Letter 15, Seneca counsels against extreme exercise and body-building, as he does against other extremes. We should make time for the soul. He is not against exercise. A little light running, jumping, and light weight-lifting is good. So is the gentle motion of riding in a litter (sort of like a rocking chair?). Likewise, one should exercise the voice, but not by shouting. Live in moderation; life is short. Here, in translation, are the opening lines of Letter 15:

It was the habit of the ancients, preserved until my time, to add to the first words of a letter, "If you are well, I am well." Rightly, we say, "If you philosophize, it is good." That is, precisely, to be well. Without it, the soul is sick; the body, too, even if it has great strength, has only the strength of a mad, frenetic person. Therefore, especially take care of the former kind of health, and give the latter second place. Which will not matter much to you, if you only wish to be healthy. For it is a foolish occupation, my Lucilius, and little fitting to a man of letters, to occupy oneself in exercising one's biceps and enlarging one's neck and firming one's flanks. When your feasting has turned out well and your bulging muscles have grown, you will never equal the strength or weight of a plump bull. Add to that, the soul is squeezed out by the extra burden of the body, and it is less agile. And so, as much as you can, limit your body and make a place for your soul. |

Quotation for August-September 2008: A review of the movie WALL-E, a robot love story, and a quotation from Homer's Iliad |

"The fantasy of a statue that comes to life is as central a fable as we have. The idea of motion or speech in an inanimate stone is an inescapable possibility, a concept of a sort so basic that we can hardly call it a metaphor. Time and again, we find texts in which the statue that stands immobile in temple or square descends from its pedestal, or speaks out of its silence. Such fantasies are simply part of what we know about statues, and what statues can represent to us..."(Kenneth Gross, The Dream of the Moving Statue)

Illustrations: Robots old and new: TOP: Bronze figures of Minerva and the Bell Ringers, by Antonin Jean Carles, 1895, from the old New York Herald Building. Now restored in Herald Square, the bronze men strike the bell with their mallets every hour; bronze owls once flashed their illuminated eyes at press time. MIDDLE: The Autoperipatetikos, or doll that Walks-by-Itself, patented by Enoch Rice Morrison in 1862. This example is in the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA. BOTTOM: Electro-Man entertaining children at a safety exhibit of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority at the 2003 open house of the Harmon Shops, Croton-Harmon, NY. (Photos by C.A.Sowa).

Moving statues

In The Dream of the Moving Statue (Cornell, 1992), Kenneth Gross, quoted above, examines the aesthetic, psychoanalytic, and historic meanings of images that come to life, and the opposing myths of the metamorphosis of the living person, like Niobe or Lot's Wife, into a statue or inanimate object. Perhaps there are in these fantasies a desire to conquer death and transcend boundaries, perhaps sometimes a fear of retribution, or even a desire to enter oneself into the stability of a stonelike state. Gross's examples range from ancient tales such as that of Pygmalion to more modern stories like Molière's Don Juan and Pushkin's The Bronze Horseman and movies like Charlie Chaplin's City Lights and Peter Greenaway's The Draughtsman's Contract. The statue that comes to life may be oracle or retribution or wish fulfillment, but stories of toys or other inanimate objects that take on a life of their own continue to be a deep-seated human fantasy.

WALL-E, the lovable trash compactor

One of this summer's most popular movies was the animated Pixar film, WALL-E. It is still in a few theaters, but if you can't catch it, rent the DVD! Although billed as a children's movie, the themes treated, concerning the destruction of the environment, the relationship of humans to machines, and the power of love (even betweeen machines!), not to mention the many witty references to other films and stories, give any viewer much food for thought.

WALL-E (Waste Allocation Load Lifter, Earth-Class), diligent and homely trash compactor, has spent hundreds of years cleaning up the toxic detritus left by human beings. The humans long ago left Earth to live, bloated and idle, like Homer's Lotus-Eaters, in resort-like exile on a space ship, the Axiom, waited upon by hundreds of robot servants. WALL-E's only companion is a cockroach. With childlike curiosity, he collects things that he finds, putting them in a box in his belly, and takes them to his home, a giant shipping container full of spare parts and his beloved junk collection. His finds include a Rubik's cube, a brassiere (which he tries to wear like a mask), and an old VCR tape of Hello Dolly, which he watches over and over. One day, he finds a single plant, growing in an old work boot. The tiny plant is his prized possession. Shortly thereafter, a space shuttle brings a sleek modern robot named EVE, whose name means Extraterrestrial Vegetation Evaluator. Her job is to discover whether Earth, based on the renewed presence of photosynthesis, that is, of plant life, is again livable. WALL-E's awkward, adolescent-like attempts to make friends with EVE are met first with icy disdain, then curiosity, on her part. Then EVE grabs WALL-E's plant with her tractor beam and puts it in her own womb-like belly, and departs on her space shuttle for the humans' mother ship. WALL-E follows her, clinging to the outside of the shuttle.

Where the first half of the film was almost wordless, the second is a slapstick farce in which the dingy and rusty WALL-E tries to evade the army of servant robots who want to clean up the mess that he represents. At last, the Captain of the Axiom, with heroic fortitude, realizes that Earth must be recolonized, and, to the strains of Also Sprach Zarathustra, wrests control from the dictatorial Auto, the autopilot computer, and steers a course for Earth. Happy humans relearn to live in Earth's gravity, and prepare to plant WALL-E's little plant, and many more of them. But WALL-E has been injured, and EVE undertakes to heal him by replacing his burned-out circuit boards. Still he is listless and depressed, until EVE takes his square hand in hers, and the spark of love unites them as the cockroach chirps happily.

WALL-E and R.U.R.

The references are many: In his bug-eyed visage and childlike nature (and his near-death experience), WALL-E instantly evokes the extraterrestrial E.T. The cockroach (they will outlive us all!) reminds us of Jiminy Cricket, the companion of Pinocchio, another toy who comes to life. The cherished plant echoes Saint Exupéry's Little Prince, with his beloved single rose. The Captain's struggle with Auto for control of the space ship parodies the struggle with the computer HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey, right down to the music from Zarathustra.

Perhaps, however, the most interesting antecedent is Karel Čapek's 1921 play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots), which gave us the word "robot." In it, the robots, built to work as slaves for humans, rebel and take over the world, killing all the humans but one, the engineer Alquist. But the robots cannot reproduce themselves, because they do not know the secret of their own manufacture, and all the plans have been destroyed. Nor do they care that when they wear out, they are destroyed, because they have no feelings. But two robots, Primus and Helena, inexplicably fall in love, laughing together and holding hands. When Alquist proposes dissecting Helena to see how she works, Primus cries out that he will die in her place, upon which Helena bursts into tears, and offers to die instead. "We belong to each other," says Primus. Alquist, deeply moved, lets them go, saying "Go Adam, go Eve. The world is yours." By developing emotions, they have become human, the key to repopulating Earth. Like WALL-E and his EVE, they have shown the human beings how to be human.

Homeric androids

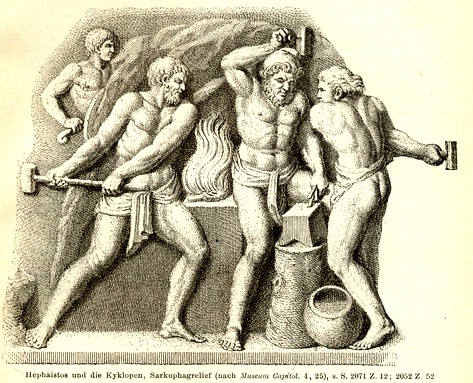

Fantasies of robots that come to life are as old as Homer. The Iliad, composed perhaps around 750 B.C., describes the intelligent golden maidservants and self-propelled golden-wheeled tripods that the lame technician god Hephaestus built for himself. For his work at the anvil, Hephaestus also built "twenty bellows in all, blowing upon the melting pots at his command." In the Odyssey, Hephaestus forged immortal gold and silver guard dogs for King Alkinoos of Phaiakia, whose navy also owned a fleet of self-propelled ships. In Hellenistic times, Heron of Alexandria (whose dates are uncertain, but who may have lived in the first century B.C.) actually built dancing mannequins of Dionysos and the Bacchants, powered by water and steam.

In Book 18 of the Iliad, Homer tells how Thetis visits Hephaestus,

asking him to make a shield and new armor for her doomed son Achilles.

As Hephaestus rises to greet her, Homer depicts the smith's skillful androids.

As we see, Hephaestus' golden young servants, "having reason in their hearts,"

even if they do not have emotions, at least possess a sophisticated form of

Artificial Intelligence.

|

Speaking thus, he rose from his anvil, a monstrous bulk, Homer, Iliad 18.410-421 |

Hephaestus at his forge (Sarcophagus relief, depicted in Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Quotation for July 2008: In honor of the man who gave birth to a child, we celebrate the seer Teiresias, who turned into a woman, then back into a man, as told in Ovid's Metamorphoses |

Hera and Zeus, quarreling over who enjoys the greater pleasure, the man or the woman, ask Teiresias, who has enjoyed both experiences. (Illustration: Hera and Zeus, metope from the Doric temple of Hera at Selinus, Sicily. About 465 B.C. Palermo, photo by R. Schoder, S.J.)

A transgendered man in Oregon gives birth to a baby girl

Welcome to the world, little Miss Beatie! Early in July, it was reported that the so-called "pregnant man," Thomas Beatie, had given birth to a healthy baby girl at a hospital in Oregon. Beatie, who was born a woman (and, it has been pointed out, chromosomally still is), underwent gender reassignment to become legally a man, but kept his female organs in order to be able to bear children. His wife, Nancy, has two grown daughters by a previous marriage, but is unable to bear more children because she has had a hysterectomy. The couple used donor sperm and Beatie's own eggs.

Gays, lesbians, and transgendered characters in poetry and mythology

We are all familiar with homosexuality in ancient culture and literature (the term "Greek love" was familiar long before "gay" entered our vocabulary), and the island of Lesbos, Sappho's home, has given its name permanently to gay women (although, of course, not all Lesbians are "lesbians"!). We also know the myth of Zeus, who gave birth to Athena fully grown from the top of his head (after swallowing her mother, Metis, according to Hesiod), and gave birth to Dionysos from his thigh, after he had incinerated the infant god's mother, Semele, with his thunderbolt.

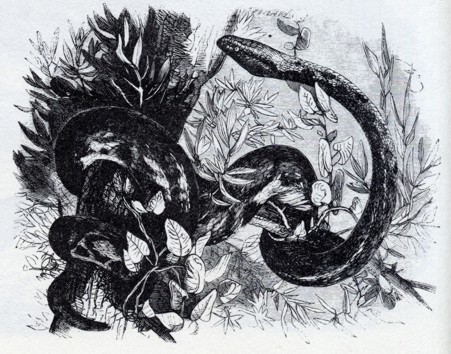

We are less aware that the transgender character can also be found in ancient mythology. The seer Teiresias, however, had this experience, when one encounter with a pair of mating snakes turned him into a woman, but another encounter with the same snakes turned him back into a man.

Teiresias' encounter with the snakes that changed his life

Teiresias, the great blind seer of Thebes, appears as a character in many ancient legends. He plays an important part in the story of Oedipus, and appears in the Odyssey as a shade in the Underworld, where alone among the dead he retains his mental faculties (phrenes and noon), and foretells Odysseus' future. There are different versions of how Teiresias lost his sight and gained the gift of prophecy. In one story, Teiresias, who had been both a man and a woman, is called upon to settle a dispute between Hera and Zeus over which sex enjoys love the most, He takes Zeus's position that the female has the greater pleasure. This angers Hera, who blinds him, but Zeus compensates him with the ability to prophesy the future. Callimachus followed a different version in his Fifth Hymn ("The Bath of Pallas"). In it, Teiresias as a youth sees Athena bathing, but since his mother, the nymph Chariclo, is a favorite of Athena, she does not put him to death, but blinds him, while also making him a prophet.

Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, follows the first of these versions. He pictures Jupiter (Zeus) and Juno (Hera) enjoying a Happy Hour of nectar and discussing the relative sexual pleasure of males and females. Remembering Teiresias' experience, they turn to him for his opinion. We translate here Ovid's version of the story. (The allusion to "twice-born Bacchus" is a reference to Dionysos' second birth from Zeus's thigh, and the "fatal oath" refers to Zeus's (now regretted) promise to Semele that he will show himself to her in his true nature -- a thunderbolt!)

While these things were happening on earth because of the fatal oath

and the cradle of twice-born Bacchus remained safe,

they say that Jove, relaxed with nectar, set aside his heavy cares

and made light jokes at leisure with Juno, and said,

"Certainly your pleasure is greater

than that which falls to the lot of the male."

She denied it. They decided to ask the opinion of the learned

Tiresias. Both kinds of love were known to him.

For he had disturbed two large serpents, mating in the green forest,

with a blow from his staff.

From a man, he became, marvellously, a woman

and lived thus for seven autumns. In the eighth, he again

saw the same snakes, and said, "If there is so much power in striking you,

that it changes the fate of the striker into the opposite, now again I shall hit you!" As the snakes were struck,

his former shape returned and the appearance he was born with.

And so the arbiter selected for this joking dispute

confirmed Jove's words. Saturn's daughter [Juno] is said

to have been offended more deeply than was justified

and not in proportion to the matter

and condemned the eyes of the judge to eternal night.

But the omnipotent father (for it is not allowed to any god

to void the deeds of another god), in compensation for lost sight

gave knowledge of the future and lightened the punishment with honor.

Ovid, Metamorphoses III.316-338.

Teiresias' first encounter with the snakes turned him into a woman, the second turned him back into a man.

Quotation for June 2008: for the summer solstice, a tipsy celebrant looks at the heavens in Ovid's Fasti |

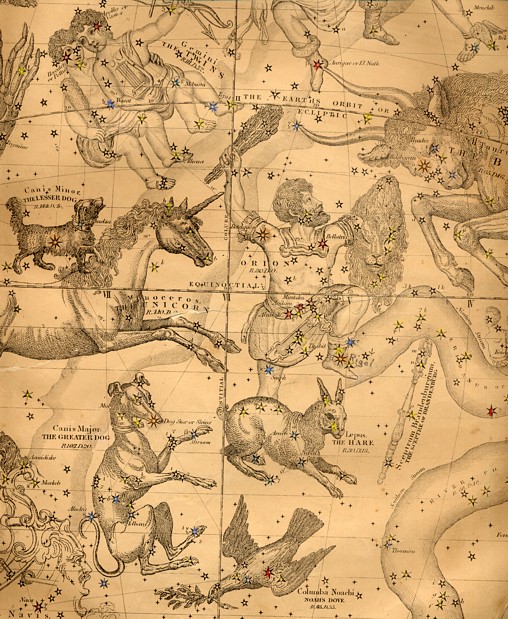

The constellation of the hunter Orion, with his dogs Canis Major and Canis Minor, in Burritt's Geography of the Heavens, New York, 1856.)

A drunk looks for Orion's belt on the wrong night

Ovid's Fasti or Roman Calendar extends only from January to June. We don't know if he never finished the year, or if the rest of the poem has been lost. His entry for the summer solstice, which falls in June, is short. A drunken man, on his way home from a shrine outside the city (a celebration of some sort?) scans the heavens in vain for Orion's belt, a few days early. (As a note in Frazer's Loeb edition explains, "True morning rising of middle star was on June 21, apparent, July 13. The summer solstice was on June 24."). The constellation of Orion is best seen in winter, when it is one of the most prominent features of the night sky. The three stars of his belt and the sword hanging from it are instantly recognizable. One of the celestial objects in his sword is not a star but a nebula, which appears as a fuzzy blob to the naked eye, but even through simple binoculars, individual tiny stars can be seen forming in a hazy cloud, a mini-Hubble picture of a distant world.

The story of Orion

There are various myths of Orion, the gigantic hunter, with conflicting versions of his life, death, and eventual apotheosis as a constellation. Homer's Calypso depicts him as the dawn goddess Eos' lover, who was killed by Artemis (Odyssey 5.121-4). Calypso cites him as an example of how the gods begrudge goddesses that they mate with mortal men. Another story has him slain by Artemis because he insulted her, or that he was killed by a scorpion sent by the goddess Earth because he boasted that he would kill all the animals. He may have been Boeotian, as there are many legends about him from Boeotia. Other stories connect him with Chios. In any case, he now roams the heavens with his faithful hunting dogs, Canis Major and Canis Minor. The prey that he hunts, Taurus the bull and Lepus the hare, are close by. (Scorpio the scorpion is kept far on the other side!)

The tipsy astonomer

Here is Ovid's amateur astronomer:

Lo, a fellow returning, not very sober, from a suburban shrine

shouts the following words at the stars:

"Your belt is hidden, and tomorrow perhaps it will be hidden,

but after that, Orion, it will be visible to me."

But if he were not drunk, he would have said

that the time of the solstice would fall on that same day.

Ovid, Fasti, 6.785-790.

Quotation for May 2008: Inflation, Roman style: Janus complains of the devaluation of the old currency in Ovid's Fasti |

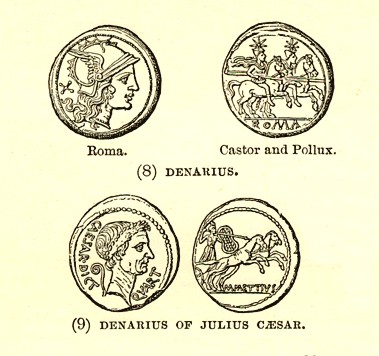

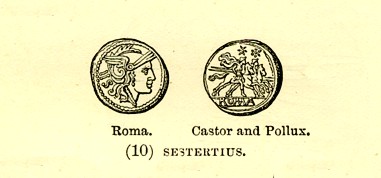

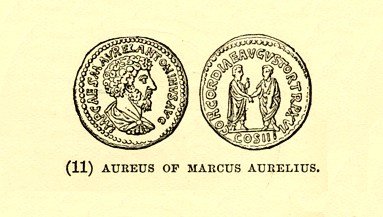

A one-as coin with Janus on one side, prow of a ship on the other (in Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899).

Inflation in today's news

Inflation is in the news. Food costs more, affordable housing is difficult to find, medical costs are up, college tuition is prohibitive, the dollar has lost its value internationally, and with gasoline at $4.00 a gallon, you can't go anywhere anyway. (Time to revive train travel!)

Ancient Rome suffered from its own kind of inflation. In early Rome and Latium, the oldest medium of exchange was oxen and sheep (hence the word for property or wealth, pecunia, from pecus "cattle" and our word pecuniary). A later currency consisted of unwrought copper or bronze (aes rude), and then of bronze bars marked with an image or inscription (aes signatum). Rome came late to using actual coins, compared to the Greek and Middle Eastern world. Lydia struck coins of electrum (an alloy of gold and silver) in the 7th century B.C., followed by the silver coins of the Greek cities of Aegina, Corinth, and Chalcis. (Prior to this, the Greeks used iron spits (oboloi) as currency; a handful of six of these was a drachme.)

Rome, however, seems not to have minted real coins until around 300 B.C. The earliest known coin was the copper one-as coin, which originally weighed one Roman pound, or twelve unciae (the word from which our word ounce comes). The obverse bore the image of Janus, the two-faced god of doorways and beginnings, the reverse the image of a ship's prow (see the depiction above). In 269 B.C. Rome opened her first mint, in the temple of Juno Moneta ("the Mindful One"; the epithet gives us, as a result, both the words "money" and "mint"). Silver coins were minted here after the Greek fashion, for the cities and outside trade, copper coins for the rustic countryside. Gold coins, too, were eventually introduced. But the stalwart old copper coins gradually decreased in weight, until they weighed only one uncia, and finally they were no longer minted. Over the course of the Roman republic and then the Empire, the silver and gold coins, too, underwent periodic decreases in weight, followed by periodic reforms.

Ovid's Janus complains of the loss of the old coinage

Ovid, in his entry for the month of January in the Fasti, describes his encounter with the weird old god Janus, in a passage of which we quoted a part in the Quotation of the Month for January, 2007. Janus, at first frightening with his strange double face that "alone of the gods, can look at his own back," turns out to be a genial ranconteur. Previously, we quoted his account of the arrival of the god Saturn, exiled from the celestial kingdom by Jupiter. Prior to this story, Janus rails against the devaluation of the old copper coins that bear his image, and their worn-out condition that makes his image unrecognizable! This rant, in turn, is the result of Ovid inquiring about the various kinds of offerings that are brought to Janus at his festival. Dates, figs, and honey are among the offerings, so that the year may be sweet. But money is brought, too, and money is even sweeter than honey! In the time of Saturn, life was simple, whereas now everything must be gold and jewels, and people make money for the sake of making money. We praise the old days, but find today more useful.

(Ironically, as we learn in Vergil's Aeneid, quoted for the Saturnalia in the quotation for December, 2007, the simple age of Saturn was also referred to as the "Golden Age"! These poets should get their stories straight!)

. . . "I see why sweets are given. Tell me also the reason for giving coins,

that no part of your festival escape me."

He laughed, and "How your own age deceives you," he said,

"who think that honey is sweeter than receiving a donation of coins!

Even in the reign of Saturn, I scarcely saw anyone

in whose heart profit was not sweet.

In time, the love of having things, which is now at its height, grew.

Now there is hardly any farther that it can go.

Wealth is now of more value, than in the years of olden times,

when the people were poor, and Rome was new,

when a small hut was large enough for Mars-born Quirinus,

and river sedge provided a humble bed.

Jupiter could scarcely stand upright in his narrow shrine,

and the thunderbolt in Jove's right hand was made of clay.

With foliage they used to ornament the Capitol, which they now ornament with gems,

and the senator used to pasture his own sheep.

Nor was it a shame to take one's peaceful rest on straw

and support one's head on hay.

The praetor gave judgment to the people, merely putting aside his plow,

and it was a crime to own a piece of light silver plate.

But since the Fortune of this place has raised her head,

and Rome has touched the highest gods with her crest,

wealth and the furious desire for wealth have grown,

and when people possess the most, they seek more.

. . .

Only worth is worth anything now; wealth brings honors,

wealth brings friendships; the poor man everywhere lies broken.

And yet you ask if an omen drawn from coin payment is useful,

and why the old coppers delight your palms!

They used to give coppers, now there is a better omen in gold.

Vanquished, the ancient money has given way to the new.

Golden temples delight us also, although we esteem the antique ones;

such majesty is appropriate for the god.

We praise olden days, but find our own times useful.

Yet both customs are worthy of being cultivated."

He concluded his admonitions. With calm speech, as before,

I addressed the god who bears the key:

"I have learned many things, indeed, but why is the figure of a ship

stamped on one side of the copper coin, and a two-headed figure on the other?"

"You could have recognized me in the double image," he said,

"if age had not blurred the workmanship.

That leaves the reason for the boat. By boat the sickle-bearing god [Saturn]

arrived at the Tuscan river, after roaming the globe.

I remember how Saturn was received in this land;

he had been driven by Jupiter from the celestial realms. . ."

(-Ovid, Fasti I.189-236)

Silver and gold Roman coins (in Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

Quotation for April 2008: Suggested by the curse buried under Yankee Stadium, a baleful poem by Horace |

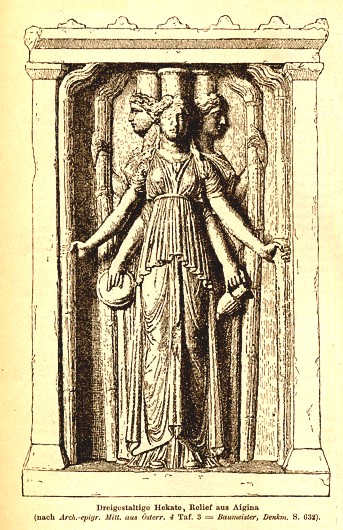

Relief of three-headed Hekate from Aegina (in Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890). Hecate, a goddess associated with the uncanny, the Underworld, and crossroads, was among the divinities invoked in curses.

The Red Sox curse on Yankee Stadium

Early in April, it became known that a construction worker building the new stadium for the New York Yankees baseball team had buried a T-shirt bearing the name of the rival Boston Red Sox in the cement floor of the stadium, in order to put a curse on the Yankees. The worker later confessed that he had buried the shirt under the floor last summer, prophesying that the curse would last 30 years. The Yankee management took the curse seriously, spending $50,000 to dig up the offending garment. When last heard, the jersey was back in Boston, where it will be auctioned off for charity. Ball players are known for being superstitious, but the idea of buried curses has deep roots in Classical culture.

Ancient curse tablets

Curses, often addressed to chthonic (underground) or liminal (boundary) deities, such as Hecate, Persephone, Hermes, or Charon, scratched on lead and pierced with nails have been found at both Greek and Roman sites. Curses or spells may also have been written on materials such as papyrus, wood, or wax, but these are more perishable. A large number of lead curse tablets have been found in Athens. Many of these refer to court cases and are designed to put an evil spell on the opposing litigant. Many have also been found in Roman Britain, especially at the Roman baths in present-day Bath, England, where they tend to be aimed at thieves who stole the bathers' clothes (apparently they didn't have lockers).

We also have what might be called "literary curses." In July, 2007, we quoted a poem by Theocritus, in which a young sorceress uses magic to try to lure back a young man with whom she had a brief affair (or maybe kill him!). Below, we quote one of Horace's Epodes, in which he wishes shipwreck on another poet, named Mevius.

Burying the St. Joseph statue

Good prayers can be buried, too. Some of the buried tablets were spells buried at grave sites to help the dead to their next life, especially if the person died young or died a violent death, and some were love spells.

Today, statues of St. Joseph (patron saint of carpenters, and thus of houses) are buried by homeowners trying to sell their houses. The statue is buried upside down in the yard, then dug up when the house is sold, and displayed in a place of honor in the new home (it is suggested that the statue be buried in a plastic bag so that it doesn't get dirty). St. Joseph statue kits, with statue, plastic bag, and directions for use, are available over the Internet. The statues come in different sizes, but there is apparently no difference in their efficacy. Some real-estate agents are said to keep supplies of these statues to provide for their prospective clients.

Horace's curse upon Mevius

Our quotation of the month is an example of the "literary curse," Horace's ill wishes for a rival poet.

Mevius (who along with another bad poet, Bavius, is immortalized by Vergil's insults in Eclogue 3.90), was apparently an enemy of both Vergil and Horace. No poetry by Mevius or Bavius survives. Mevius was about to embark on a trip to Greece. Horace calls on all the hostile winds (Auster and Notus, the south winds, Eurus, the east wind, and Aquilo, the north wind) to wreck Mevius' ship. He does not call on Zephyrus, the gentle west wind. Horace's ill-omened sendoff (Epode X), translated below, was modeled on a poem by Archilochus.

Under an evil augury the ship departs,

bearing the stinking Mevius.

Auster, may you lash both her sides,

-- remember! -- with horrible waves.

Let black Eurus scatter rigging

and broken oars on the sea turned upside down.

May Aquilo rise up, mighty as when in the high mountains

he breaks the trembling oaks.

May no friendly star appear in the gloomy night

from which sad Orion sets.

Nor let him be borne on a more quiet sea

than was the Greek band of victors,

when Pallas turned her ire from burning Ilium

against Ajax' impious vessel.

O how much toil awaits your sailors,

and for you, yellow pallor

and that non-manly wailing,

and prayers to Jupiter, who turns away,

when the Ionian Sea, bellowing in wet

Notus, wrecks your ship.

But if as fat prey on the curving shore,

stretched out, you bring pleasure to the sea birds,

a libidinous goat will be sacrificed

with a lamb to the Tempest deities.

Mercury (Hermes) in his role as psychopompos, or conductor of the souls of the dead into the Underworld.

Quotation for March 2008: For the"March Madness" basketball championships, Nausicaa and her maidens play ball in the Odyssey |

Athenian women filling their water pots at a public fountain

and chatting (black-figured water pot (hydria), 6th cent. B.C. Paris, Louvre.

(image from Rostovtzeff, History of the Ancient World, after Perrot and Chipiez.)

Festivals and games of March

The month of March 2008 has provided us with many occasions for festivals -- St. Patrick's Day, the celebrations of Purim and of Mohammed's Birthday, the Spring Equinox, and Easter. It also gives us March Madness, the annual National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Men's and Women's Basketball Tournaments. Since Title IX of the Education Amendments was passed in 1972, women's sports, including basketball, have received more prominence, although American women have always found ways to satisfy their desire for athletic competition (as illustrated by the antique picture at the bottom of this item!)

In the Greek and Roman world, many kinds of ball games were played, by men and women, young and old. This month's quotation is from Homer's Odyssey, describing the ball game played by the Phaeacian princess Nausicaa and her handmaidens while their clothes dry on the beach -- setting them up to discover shipwrecked Odysseus in time to aid him on his return home to Ithaca.

Athena stage-manages a rescue for Odysseus

Odysseus has left Calypso's island on a stout raft that Calypso helped him build, but which the angry god Poseidon quickly turns to kindling wood. Buoyed by a magical veil given him by the goddess Ino (who used to be human herself), Odysseus swims to the rocky shore of the island of Scheria, home of the Phaeacians. Naked, covered with brine, and dead tired, he crawls under some bushes to sleep. The goddess Athena, his patron, always clever and vigilant, contrives a way to get him the rest of the way home. She puts a dream into the mind of Nausicaa, daughter of King Alcinous, reminding her that she must wash her clothes, because she can expect soon to get married. Nausicaa coyly asks her father for the mule-chariot, omitting the idea of marriage but saying that she must wash her brothers' clothes. But Alcinous "understands everything" and lets her go. Nausicaa and her attendants take a picnic lunch and wine with them, and Nausicaa (a down-to-earth princess) drives the mule-chariot herself as they take the laundry to the washing-pits by the beach.

After doing the washing -- which they turn into a competition -- and eating lunch, they play a game of ball. Athena again intervenes, making Nausicaa miss her throw and send the ball into the water. The girls shriek, and Odysseus wakes up. A comic scene ensues, as Odysseus, covering his nakedness with a branch, tries to figure out where he is, and whether the girls are nymphs or mortals. Eventually he is invited to wash up and eat something, and Athena "pours charis [beauty and charm] over him," making him incredibly appealing to Nausicaa. Again being coy, Nausicaa insists that he go by himself to ask for the king's aid, rather than accompanying her -- so that gossips won't start rumors about them! Her father again gets the point, and gently scolds her for her silliness. Eventually, Odysseus tells his tale to the Phaeacians and is at last sent back home to Ithaca. And the rest, as they say, is history.

Note on mythic themes

(NOTE: In terms of epic themes, Nausicaa's ball game represents a variation on the theme of "Maidens Dancing and Picking Flowers (Interrupted by a Scary Male Figure)," one of the themes identified in my book Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns.)

Here is the story of Nausicaa's ball game.

But when they came to the beautiful stream of the river,

where the capacious washing troughs were, and plenty of good water

flowed up from beneath them, enough to clean clothes no matter how dirty,

there they unhitched the mules from the wagon,

and drove them beside the eddying river

to graze on the honey-sweet wild grass. From the wagon

they took the clothes in their arms and carried them to the black water,

and trampled them in the pits, speedily competing with each other.

But when they had washed the clothes and cleaned off all the dirt,

they spread them out in a row along the shore of the sea, where

the pebbles were washed cleanest by the waves against the land.

Having bathed and anointed themselves with rich oil,

they took their lunch by the banks of the river,

and waited for the clothes to dry by the rays of the sun.

But after she and her handmaids had enjoyed their food,

they played a game of ball, having thrown off their headgear.

White-armed Nausicaa led in the song.

Just as Artemis the archer roves over the mountains,

along the heights of Taygetus or Erymanthus,

rejoicing in the boars and swift deer,

and with her the country nymphs, daughters of Zeus who bears the aegis

sport with her, and Leto [mother of Artemis] rejoices in her heart,

and she herself holds her head and brow above all the others,

and so is easily recognized, although all are beautiful --

just so the unwed maiden stood out among her attendants.

But when she was ready to go back home,

yoking the mules and folding the beautiful clothes,

then the goddess, gray-eyed Athena, thought of something else,

how Odysseus should wake up and see the fair-faced girl,

and she would lead him to the city of the Phaeacians.

The princess threw the ball to one of her attendants,

but she missed the attendant, and threw the ball into the deep eddy.

They gave a long shout, and godlike Odysseus awoke;

sitting up, he wondered in his heart and mind,

"Oh my, to the land of what men have I come...

(Homer, Odyssey 6.85-119)

Quotation for February 2008: For Valentines' Day, a love poem by Sappho |

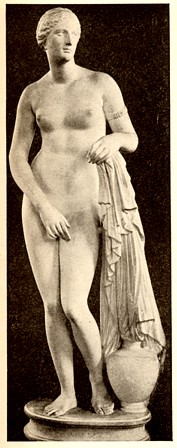

Sappho's poems celebrate her women friends

Sappho (b. 612 B.C), the great lyric poetess from the island of Lesbos, is known to us only in a few poems preserved in other authors and in fragmentary papyri. From these remains and from glowing opinions of ancient authors, we get an idea of what we are missing: Plato (in the Phaedrus) called her "the tenth Muse." She is known for her passionate love poems to women friends, and has forever bequeathed the name of "lesbian" to all women who love women. There were, of course, other Lesbians who were not "lesbian," including her contemporary and friend, the poet Alcaeus, author of drinking songs, love songs, and odes against tyrants, reflective of the turbulent political times on Lesbos in which both of them lived.

The legend that Sappho threw herself off a cliff into the sea for love of a man named Phaon was apparently invented, but she does seem to have married and had a child. Her greatest affections and emotional attachments, however, were to a group of women friends, who perhaps formed a cult of Aphrodite and the Muses.

"Longinus," in On the Sublime (Peri hypsous; the actual author, probably of the first century A.D, is unknown), quoted the poem by Sappho that we translate below, of which he included, unfortunately, only the first four stanzas. Some lines have been supplemented by papyrus fragments. The poem describes Sappho's jealousy at seeing a man enjoying the favors of a woman whom Sappho adores. She describes in detail the physical symptoms of her emotions -- recognizable to both heterosexuals and homosexuals -- as she "falls to pieces" (to quote the song by Patsy Cline!) upon seeing the object of her desire. Longinus aptly notes that where some authors "attract the listener by their selection of elements, and others do so by the way they pack them together," Sappho "excels in both choosing and combining the most intense and striking symptoms" of love.

Here, in Greek and English, is Sappho's description:

He seems to me the equal of the gods

that man, who sits across from you,

and, near you as you sweetly speak,

listens to you,

and as you laugh your lovely laugh, a thing that

makes my heart in my breast beat wildly;

for when I see you, even briefly, my voice

refuses to come,

my tongue is broken, and a delicate

fire suddenly runs across my flesh;

there is no sight in my eyes,

and my ears hum;

sweat runs down me, a trembling

seizes me all over, and I am more green

than grass; I am little short of dying,

it would seem.

But all must be endured, since...

Sappho, No. 2 (fragmentary)

Decoration from Longus, Daphnis and Chloe: A Pastoral Romance, English translation, 19th cent., engraving after a design by the Regent, Philippe d'Orléans for an edition of 1718.

Quotation for January 2008: Women warriors in Herodotus, suggested by the candidates in the U.S. presidential election |

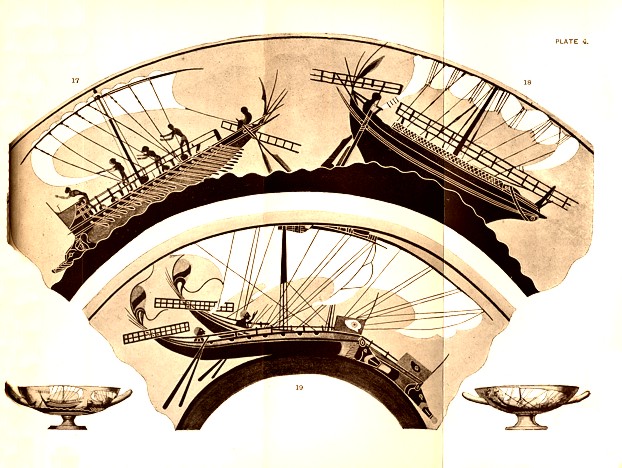

Illustration: Nos. 17 and 18 (upper), war ship and merchant ship, about 500 B.C, from a painted vase found at Vulci in Etruria, in the British Museum; No 19 (lower), two war ships, about 500 B.C., from a painted vase by Nicosthenes found at Vulci in Etruria, in the Louvre. From Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895.

Women warriors

With the candidacy of Hillary Clinton, we may have, for the first time, a woman President of the United States, and thus a female Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. Ancient literature furnishes us with some colorful and outstanding women leaders, including Vergil's half-mythic Dido, Queen of Carthage; Boudicca, who led a revolt against Roman rule in Britain; and, of course, Cleopatra of Egypt. Herodotus (c. 484-430? B.C.), in his Histories, describes several very able women who led their cities in peace and war, including two queens of Babylon, Semiramis and Nitocris.

Herodotus gives the fullest account of Artemisia, queen of Halicarnassus, his own native city, which, although at least partially Greek, was at the time a part of the Persian Empire. In his account of the wars between the Greeks and the Persians, Artemisia is depicted as giving wise counsel to the Persian king Xerxes, who foolishly rejects her advice. She advises him NOT to attempt a naval battle against the Greeks. He need not take the chance, she says, as he had already taken Athens, thus attaining his principal objective. For, she says, the Greek men "are as superior at sea to your men as men are to women." It would be more advantageous to wait until the Greeks ran out of provisions, or to invade the Peloponnesus and split the Greek coalition. Xerxes, spurning her advice, nevertheless engaged the Greeks at Salamis, off the coast near Athens, causing the destruction of the Persian navy. At Salamis, commanding her own ship, Artemisia fought with valor (if perhaps with questionable ethics, as described in the quotation below). After Xerxes' defeat, she again gave wise counsel, telling him to, as we would say "declare a victory and leave." This time, he takes her advice, retreating to Persia and leaving the fight to the warlike Mardonius, who was to meet his own defeat in the final battle at Plataea, in Boeotia.

Artemisia at Salamis

In the great sea battle of Salamis (480 B.C.), in which the Athenians under Themistocles defeated the Persian navy, Artemisia performed an exploit that was either clever or ruthless, or maybe just fortuitous. Hemmed in by Greek ships on the one side and Persian and allied ships on the other, she rammed and sank one of her own allies. The Greeks thought that hers was a Greek ship that had rammed a Persian and stopped chasing her. Xerxes, on the other hand, assumed she had rammed a Greek, and uttered the famous words, "My men have become women, and my women have have become men."

As for the rest, I cannot accurately describe what part each of the barbarians or Greeks played in the battle. Concerning Artemisia, however, the following incident occurred, because of which she gained an even greater reputation with Xerxes. When the king's situation had turned into complete confusion, Artemisia's ship was pursued by an Attic vessel. Unable to flee (for before her were friendly ships, and her ship happened to be closest to the enemy), she thought of the following plan, which, when carried out, turned out to her advantage.Pursued by the Attic ship she rammed the ship of an ally, on which were Calyndians and the Calyndian king himself, Damasithymus. Whether she had had some quarrel with this man, while they were still at the Hellespont, I cannot say, or even whether she did this on purpose, or whether it happened by chance that the Calyndian ship got in her way. And so she rammed the ship and sank it, and by good fortune she gained a double benefit. The captain of the Attic trireme, when he saw her ramming the barbarians' ship, thought that Artemisia's ship was either Greek or a barbarian ship that had deserted and was helping his side, and turned away to chase others.

By her actions it happened, on the one hand, that she escaped and was not destroyed, and on the other hand, she was even more highly esteemed by Xerxes. For it is said that the king, who was watching, observed the ship being rammed, and one of the bystanders said, "My Lord, see how well Artemisia is fighting, and that she has sunk one of the enemy's ships?" He asked whether it was truly Artemisia's deed, and they told him that they clearly recognized her ensign. They assumed that the ship that was sunk was an enemy. In addition to her other good luck, it is said that there were no survivors to accuse her. Xerxes is reported to have said, upon being told, "My men have become women, and my women men." That is what they say Xerxes said.

Herodotus Histories VIII.87-88.

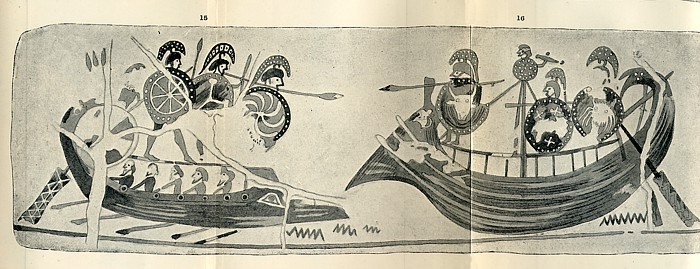

Illustration: Nos. 15 and 16, two war ships in action, about 550 B.C., from a painted vase by Aristonophos found at Caere in Etruria, in the New Capitoline Museum at Rome. From Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships, 1895.

---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2007 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: