These are quotations for the year 2010. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2010, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2010 |

Below are quotations for the year 2010. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2010

Click on a link to read each quotation

2010

- December 2010: The bears, celestial and sylvan, hibernate: Callisto's story (Ovid, Metamorphoses II 466-507).

- November 2010: At Thanksgiving, we have Prometheus to thank for the succulent meals we enjoy on feast days (Hesiod Theogony 535-560).

- October 2010: for Halloween, a journey to the Underworld by a very small insect (Vergil's Culex).

- September 2010: The evils of religious fanaticism (from Lucretius' De Rerum Natura).

- August 2010: On a summer day, the bees collect honey and stock their hives (Vergil's Fourth Georgic).

- July 2010: We have the IPad and Kindle, but what "tablets" did Homer's heroes use? (Bellerophon's cryptic message in the Iliad.

- June 2010: on the oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico: If you go too deep or too high, the gods will get even ( Otus and Ephialtes storm Olympus, as told in Odyssey Book 11).

- May 2010: Gerrymandering for a good cause: The reforms of Cleisthenes vs. entrenched special interests (Aristotle's Constitution of Athens).

- April 2010: For Arbor Day and Earth Day, Aphrodite entrusts the baby Aeneas to the tree nymphs (Homeric Hymn V to Aphrodite).

- March 2010: Happy Exelauno Day! (March Fo(u)rth). The March of the Ten Thousand Greeks (Xenophon's Anabasis).

- February 2010: For Valentine's Day, Greek goddesses as ancient "cougars," ageless beauties who seduce attractive young men. Circe and Calypso and Odysseus, Eos and Tithonus (and others!), Aphrodite and Anchises.

- January 2010: For Martin Luther King, a prophetic dream in Vergil's Aeneid.

Quotation for December 2010: The bears, celestial and sylvan, hibernate: Callisto's story (Ovid, Metamorphoses II 466-507) |

Ursa Maior (at the bottom of the picture) and Ursa Minor (with his tail swinging around the North Star), with one of Bootes' hounds just visible beneath the she-bear's tail. Bootes himself, containing the star Arcturus (the "Bear-Warden") is out of sight (depicted on another chart). From Burritt's Geography of the Heavens, New York, 1856.

The stars are bright, but the bears hibernate

In winter, the night sky is clear, the stars brilliant. Among the constellations that can be seen is the Great Bear, Ursa Maior, within which is the group of stars called the Big Dipper, its ladle pointing to the North Star. It was the "Drinking Gourd" followed by runaway slaves in the pre-Civil War South, using it to find their way to freedom in the North. While the Great Bear is visible in the Northern Hemisphere all year long, it is best seen in April. In winter it is low in the sky. But of course! She's hibernating! The bears who populate the forests near where I am writing this, in New Jersey and in Westchester County, New York (that's why a local pinnacle is called Bear Mountain!) are hibernating, too. The Chicago Bears football team, on the other hand, have made the playoffs, but if they lose, they will hibernate, too. Go Bears!

Callisto and Arcas

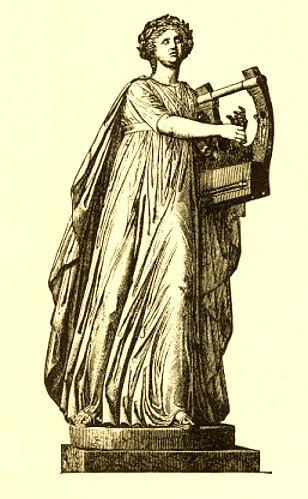

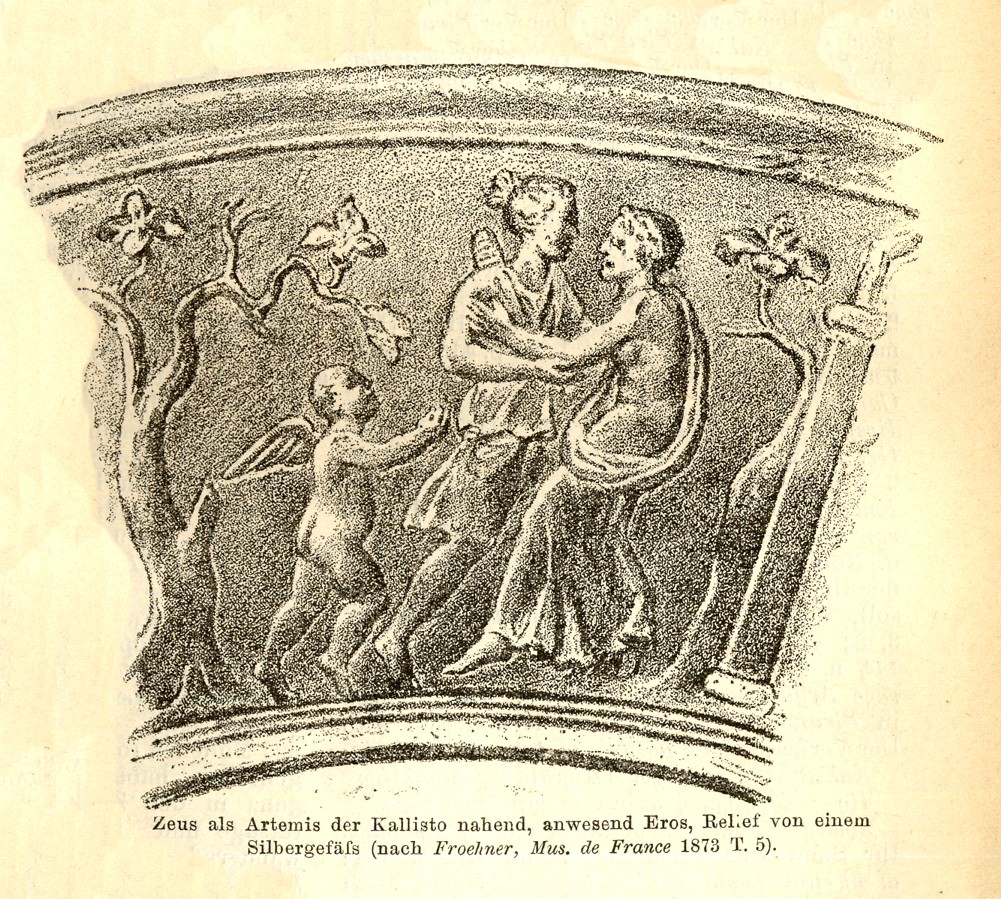

The most commonly told tale about the Great Bear is that she was once a nymph named Kallisto ("Most Beautiful"), who was one of the band of nymphs who hunted in the forest with the goddess Artemis. Zeus made love to her, and she gave birth to a son, Arcas. Hera, out of jealousy, turned her into a bear. One day, Arcas, grown up, encountered his mother in the forest and was about to kill her. Zeus snatched them up and made them into the constellations of the Great Bear and the Lesser Bear.

As always with the Graeco-Roman myths, the neat story masks a dense tangle of local cults and conflicting narratives. Artemis seems to belong to one of the oldest strata of Greek worship, localized particularly in Arcadia and Attica (Arcas, Kallisto's son, is the mythic founder of the Arcadian race). As Farnell described her in Cults of the Greek States, she is, in cult, a primitive goddess of wild animals and wild trees, protectress of those (including animals and women) who were with young. (In Brauron, girls reaching puberty dressed as bears and danced the arkteia or Bear Dance, and women in childbirth would cry out to Artemis.) Only in later myth does she become the chaste hunter of game, especially the stag, goddess of the moon and sister of Apollo. She is to be contrasted with Demeter, goddess of a settled society, whose chief concern is with the grain and agriculture. Farnell found evidence of totemistic suvivals in the worship of Artemis, in which she is the stag, the boar, the quail, or bear. The nymph Kallisto, whose father is Lykaon ("Wolf"), may in fact have originally been simply the goddess herself — one of Artemis' epithets is Kalliste, "Artemis Most Beautiful" — in her character as the Bear Goddess. The change into a constellation is a late embellishment.

Ovid's take on the matter

Ovid (writing in Latin, of course, so Artemis becomes Diana and Hera becomes Juno), gives us, as usual, a smoothly flowing, funny, and poignant telling of the story, tying together older and newer myths and connecting them cleverly to other stories as he goes along. In his telling, the story of Callisto comes after that of Phaethon, who foolishly insisted on driving the sun-chariot of his father, Apollo. Unable to control the horses, he nearly incinerates the Earth, who pleads with Jupiter to stop the conflagration. Jupiter, having no clouds or rain to pour (the fire dried them all up) strikes Phaethon with his thunderbolt. As he goes about surveying the damage, he sees Callisto. Disguised as Diana, he ravishes her and she becomes pregnant. She hides her condition, but is "outed" when Diana suggests a skinny-dipping party with her nymphs, and she is kicked out of Diana's company. When Juno exacts her revenge, Ovid depicts (as with other transformations in the Metamorphoses) Callisto's confusion and disorientation at her new, strange, furry body. Her mind stays the same (mens antiqua...mansit), and she fears wild beasts, forgetting that she is one! When Jupiter turns mother and son into constellations, Juno exacts more revenge: she makes the sea gods Tethys and Oceanus promise that the shameful pair will never dip into the sea — in other words, they never sink below the horizon.

Ovid, Metamorphoses Book II vv. 466-507

Senserat hoc olim magni matrona Tonantis |

Callisto becomes a bear, then a constellation

The wife of the great Thunderer had long known this [that

Jupiter ravished Callisto] |

Zeus (Jupiter), disguised as Artemis (Diana), approaches Kallisto. From Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.

Quotation for November 2010: As we bask in the glow of our Thanksgiving holiday, we have Prometheus to thank for the succulent meals we enjoy on feast days (Hesiod Theogony 535-560) |

Prometheus chained to his rock, the eagle waiting to pounce, while Zeus looks on. In 1970, IBM began work on an experimental machine, calling the endeavor the Prometheus Project. The machine unfortunately never went into production, but this painting was commissioned, and hung in the project manager's office.

Prometheus cuts up the sacrificial ox, giving the best part to mortals

Hoping that you all had a nice Thanksgiving, we offer a story from Hesiod's Theogony, in which he tells why mortals have Prometheus to thank for their tasty meals on festival days.

There were many stories about Prometheus. The best known today are his stealing of fire from the gods and giving it to mankind, and his subsequent chaining by Zeus to a rock, where an eagle munched by day on his liver, which grew back each night. He also participates in the story of Pandora, the first woman, who let all the evils out of the jar. (These large jars — often several feet tall — were used for storage; the word is often mistranslated as Pandora's "box.") Prometheus ("Forethought") wanted nothing to do with her, but his bumbling brother Epimetheus ("Afterthought") married her despite his brother's warnings. But there were other stories, too, including one in which Prometheus himself created the mortal race. Pausanias, in his Description of Greece (2nd cent. A.D.) tells of the town of Panopeus in Phocis, where large clay-like boulders, which "smell very like the human body" are thought to be the leftovers of the clay out of which Prometheus fashioned the first humans (Pausanias 10.4.4). There was another story, from which this month's Quotation comes, in which Prometheus instituted the practice of giving only the bones of a sacrificial animal to the gods, and keeping the best parts of the meat for the human participants.

Prometheus as trickster and populist

Prometheus, like Zeus, was descended from the older generation of the gods, the Titans, who came before the Olympians, and were at war with them. He was the son of Iapetus, who was an older brother of Kronos, father of Zeus. Iapetus and Kronos were sons of Ouranos and Gaia, "Heaven" and "Earth." (Prometheus is thus Zeus's cousin.) He seems to have been a trickster god (like Hermes or the Native American Coyote), and was particularly worshipped by craftsmen, especially in Attica, where he was associated with Hephaestus, the smith-god, and with Athena as goddess of crafts (See Farnell, Cults of the Greek States 5.378). In myth, he had an ongoing feud with Zeus, against whom he always sided with the mortals.

Hesiod tells two versions of the Prometheus story in his Works and Days and Theogony. In the Works and Days (vv. 42-105), the tale illustrates the reason man must work for a living instead of enjoying an easy life. Zeus hid fire, but Prometheus stole it in a hollow fennel stalk and gave it to man. Zeus retaliated by having Hephaestus and the other gods create Pandora. Athene taught her needlework and weaving, Aphrodite gave her grace, but Hermes made her deceitful. Given to Epimetheus, she let the evils out of the jar. Only Hope remains. (If Hope was in the jar, too, is it an evil? Endless discussion surrounds this point.) The name "Pandora" ("All-Gifts") points to her origin as an original Earth goddess.

In the Theogony (vv. 507-616), Hesiod begins with Prometheus' punishment on the mountain top, his liver eaten daily by the eagle. (The medical fact of the liver's regenerative capacity has led some to speculate that ancient physicians were aware of this phenomenon, but this view has been challenged.) Prometheus is ultimately rescued by Heracles. The reason for Zeus's wrath is Prometheus' unequal distribution of meat to men and gods "after the separation at Mecone." Ekrinanto can either mean gods and men "were separated," meaning that previously they had always eaten together, or "had a dispute." Mecone was an old name for Sicyon, a town west of Corinth. Prometheus gave the men the meat, hidden under an ugly hunk of ox stomach, but gave Zeus bare bones covered attractively in fat. In anger, Zeus hid fire, which Prometheus promptly stole and gave to mortals. Zeus retaliated by creating the first woman (she has no name here), to make mischief for men and take all their money. A long rant follows about ungrateful women and kinsfolk. But, Hesiod says, if you don't get married, there will be no one to tend you in your old age!

Below is the description of the feast at Mecone, an aetiological myth explaining why "From that time on, the tribes of men upon the earth burn white bones to the immortals upon fragrant altars."

Hesiod, Theogony vv. 535-560

|

Prometheus cheats Zeus

When the gods and mortal men separated from each other |

Portrait of Pandora (yes, she likes to open boxes!). Also known as the Calico Diva — at any opposition, she will swat you with her paw!

Quotation for Halloween, October 2010: A journey to the Underworld by a very small insect (Vergil's Culex) |

Tableau of skeletons acting out the dance of Los Viejitos ("The Little Old Men"), for el Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, from Olvera Street in Los Angeles. (Skeletons acting out a boating scene and playing a saucy peasant girl have appeared in illustrations for other Halloween quotations.) The dance of Los Viejitos is from the Mexican state of Michoacán, where young men pretend to be old men who suddenly limber up their creaky bones to dance enthusiastically. The caption over the dancers says ¡ Pinches viejitos que bien bailan! "Damn, those little old men dance well!"The little skeleton figures are a parody. This month's Quotation of the Month is also a parody, of the traditional heroic theme of the Journey to the Underworld, with an insect as epic hero.

A gnat saves a goatherd's life but pays the ultimate price

This month's quotation is from a Journey to the Underworld, not the journey of Odysseus (Odysssey Book 11) or of Aeneas (Aeneid Book 6), but of a lowly insect.

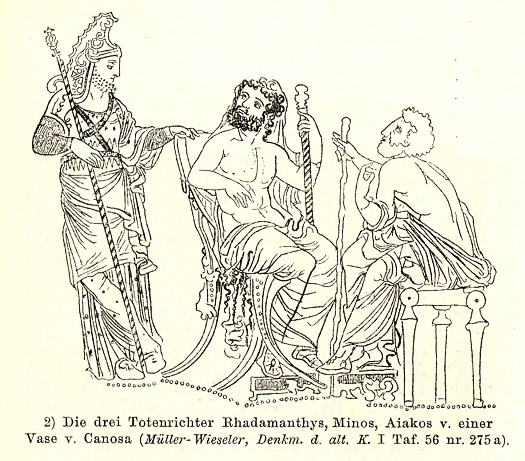

The Culex (The Gnat) is one of the poems of the Appendix Vergiliana, ascribed to Vergil, but of uncertain authorship. One afternoon in a sunny wood, as his goats rest beside a spring, a herdsman falls asleep. Unbeknownst to him, an enormous serpent, also seeking respite from the heat and angry that the man has invaded his territory, prepares to attack him. A gnat, "a little nursling of the marsh" (parvulus...umoris...alumnus) notices just in time and warns the herdsman by stinging (biting?) him in the eye (ouch!). The herdsman jumps up and crushes the gnat, killing him. Then he sees the snake, and tearing off a tree branch, kills it. Later that night, as he falls asleep, the ghost of the gnat appears to him, and reproaches him for his ingratitude. The gnat-spirit recounts his terrifying journey to the Underworld, swept along by the winds over desolate regions. He, like those more famous wanderers, sees the mythic monsters, the great sinners and heroes, heroines like Medea and Alcestis. He feels particular sympathy for Eurydice, who, like himself, is punished for the misdeed of another. For it was Orpheus, not she, who disobeyed by looking back. (The story at this point deviates from the usual version, for here she, too, was forbidden the backward glance.) Like Aeneas, he sees heroes of Roman history, like Horatius and Camillus. The little insect can only wonder at the great myths acted out before him. We could say, in fact, that the gnat is, so to speak, a fly on the wall in the Underworld! ("Let them flourish in their fame" (Illi laude sua vigeant), he says, somewhat sarcastically.) Finally, he must appear before King Minos, who with Rhadamanthys and Aiakos, was one of the mythic judges of the Underworld, to be judged, while the goatherd, who caused his misfortune, is not even there to serve as character witness. "I depart, never to return" (Digredior, numquam rediturus), he says, and "with these last words, sadly goes away" (extrema tristis cum voce recessit).

The herdsman awakes, feeling terrible about the gnat, and builds a shrine to the insect, a mound of earth planted with blooming flowers, surrounded by a stone wall. On it he places an inscription:

PARVE CULEX, PECUDUM CUSTOS TIBIT TALE MERENTI

FUNERIS OFFICIUM VITAE PRO MUNERE REDDIT.

LITTLE GNAT, THE GUARDIAN OF THE FLOCKS PAYS YOU, WHO SO DESERVE IT,

THE DUTY OF A FUNERAL IN RETURN FOR THE GIFT OF LIFE.

Whether by Vergil or not, the poem echoes Vergil's tender empathy for both the greatest and the smallest creatures (compare the excerpt from the Fourth Georgic quoted last August). Sunt lacrimae rerum "there are tears for things," as Vergil has Aeneas say in the Aeneid, viewing portraits of his own dead friends in murals of the Trojan War on Dido's walls.

Below is the passage in which the ghost of the gnat appears to the herdsman. Erebus, god of darkness and the Lower World, was brother of Night. The story of Otus and Ephialtes, who tried to pile the mountains Pelion and Ossa on Mount Olympus to reach the home of the gods was told in the Quotation for June 2010. Tityos attacked Leto (Latona) and was killed by her children Apollo and Artemis. In the Underworld, vultures gnaw at his liver.

Vergil,Culex, vv. 203-239

Iam quatit et biiuges oriens Erebeis equos Nox

|

The ghost of the gnat reproaches the shepherd

Now Night, rising from Erebus, was urging on her two yoked horses

|

King Minos as one of the judges in the Underworld (image from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890).

Quotation for September 2010: The evils of religious fanaticism (from Lucretius' De Rerum Natura) |

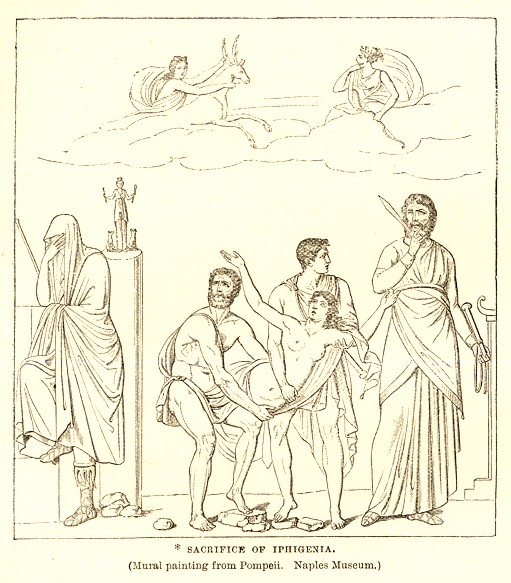

The sacrifice of Iphigeneia, from a Pompeiian wall painting. Lucretius cited the killing of Iphigeneia by her father Agamemnon as an example of the perversion of religion. (Illustration from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

The madness of fanatics

Nine years ago, a small group of religious fanatics, taking it upon themselves to act in the name of Islam, destroyed the World Trade Center in New York, killing over 2700 people who were inside. On the anniversary of that event, a group of demonstrators acting in the name of ultra-patriotism shout anti-Muslim slogans, attempting to block construction of an Islamic center and mosque a few blocks from the site. And in Florida, the pastor of a tiny Christian church (50 members) threatened to burn copies of the Muslim holy book, the Quran. In their ranting, the anti-mosque faction cares little that Muslims, as well as Christians, Jews (and probably members of other faiths) were among the victims of the tragedy. (Perhaps the entire neighborhood should be declared a religion-free zone? This would be bad news for historic Trinity Church and St. Paul's Chapel, which is literally across the street from the WTC.) How sad that the World Trade Center, whose towers once inspired the worldwide aspirations of inhabitants and immigrants alike, might become a symbol of xenophobic and religious strife. (I wrote of its earlier symbolism in "The World Trade Center as a Mythic Place".)

I am reminded of nothing so much as Lucretius' words in his great poem of scientific exposition De Rerum Natura ("On the Nature of Things"), as he describes the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, victim of her father Agamemnon's misguided beliefs:

Tantum religio potuit suadere malorum.

"So many evils did religion have the power to provoke!"

Lucretius explains Epicurus' natural history and atacks superstition

Titus Lucretius Carus (94?-55? B.C.), Roman poet of the generation before Vergil and Horace, wrote his didactic poem De Rerum Natura ("On the Nature of Things") in six books to explicate the physical theories of the Athenian philosopher Epicurus, founder of Epicureanism. The words "epicure" and "epicurean" have become debased in common parlance to mean "living for pleasure in fine dining and drinking." Epicurus indeed believed that pleasure (hêdonê) was the highest good, but the best kind of pleasure was the mental calm that results from the taming of desire and the abolition of supersitious fear of the gods and death. Epicurus, building on the theories of Democritus, put forth an early atomic theory, that the entire universe is composed of atoms and void. The universe is infinite, and contains many worlds. The soul, like the body, is composed of atoms, which disperse upon the death of the body. Even the gods are made of the very finest atoms, living tranquilly in the spaces between worlds, not concerning themselves with the affairs of human beings.

Lucretius is scathing in his denunciation of religio ("false religion" or "superstition," which he connects to religare "to bind," as we see in Book 4 line 7, where he speaks of the "freeing the mind from the tight bonds of religio"). In the prolog to Book I, he exhorts his patron Memmius to be not afraid of thunderbolts and other horrors visited by angry gods. However, Lucretius (like Epicurus) was not opposed to all belief in the gods. In fact, the De Rerum Natura is dedicated to Venus, as giver of all things procreative and lovely, and as the personification of the principle of Love. He condemns the perverted religion that inspires evil deeds. His prime exhibit is his impassioned description of the sacrifice of Iphigeneia by her father Agamemnon upon his departure for the Trojan War.

Iphigeneia sacrificed to speed the fleet

The story of Iphigeneia was told by many poets and dramatists, with many different variations. In the version followed by Lucretius (its origin was in the lost epic Cypria), the Greek fleet, setting out for Troy, was detained at the port of Aulis by a contrary wind sent by Artemis, angry at some offense given her by Agamemnon, the Greek commander. Agamemnon could atone only by sacrificing his eldest child, Iphigeneia. She, brought to Aulis under the false pretense that she was to be married to Achilles, was slain, and the fleet sailed. Aeschylus also used this version. In the Agamemnon, the killing of their daughter was the main reason Clytaemnestra killed Agamemnon on his return from Troy, setting the stage for Clytaemnestra's murder by their son, Orestes, who, pursued by the Furies, was (in the Eumenides) acquitted of matricide by the Council of the Areopagus under the leadership of Athena. In other versions of the story (in the Cypria and in Euripides), Iphigeneia does not die, as Artemis substitutes an animal (a deer or a bear) as sacrifice (compare the story of Abraham and Isaac) and the young princess becomes a priestess in Artemis' temple at Tauris.

Below is Lucretius' story. The "Virgin of the Crossroads" (Triviai virginis) is Artemis. Note the sarcasm of prima virorum "foremost among heroes," or, as we might say, "the flower of manhood." Iphigeneia ("Mighty Born") is here called "Iphianassa" ("Mighty Mistress"). The entire scene, with the red and white wool fillet tied around the victim's head, describes a typical Roman sacrifice, although many words suggest the wedding that was not to be.

Lucretius,De Rerum Natura, vv. 85-101

Aulide quo pacto Triviai virginis aram

|

The sacrifice of Iphigeneia (Iphianassa)

. . . As when at Aulis the Crossroad Virgin's altar

|

A portrait of Lucretius. (Illustration from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

Quotation for August 2010: On a summer day, the bees collect honey and stock their hives (Vergil's Fourth Georgic) |

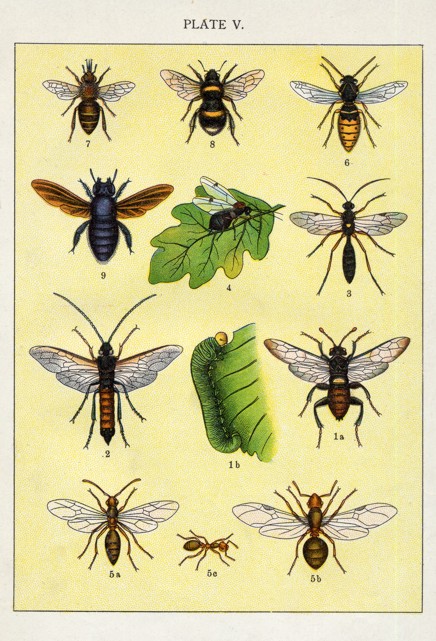

Insects of the order Hymenoptera, including wasps and bees. In the upper left corner is a worker bee of the species Apis mellifica, or Common Hive Bee. (Illustration: plate from A.W. Kappel and W. Egmont Kirby, Beetles, Butterflies, Moths, and Other Insects, 1893.)

The bees of summer

Vergil's Georgics ("Agricultural Matters"), completed in 30 B.C., consist of four books of didactic poetry, describing the essentials of Mediterranean farming. Their composition came between his early pastoral Eclogues and his epic Aeneid. Book I is about crop-raising, Book II about trees and vines, Book III about cattle, and Book III about bee-keeping. The name is Greek; Geôrgiká is from gê "earth" and ergon "work." The poems were "inspired by" Hesiod's Works and Days (Erga kai Hêmerai). But in both content and style, Vergil's poems are different from the aphorisms of the curmudgeonly old Greek poet's "Old Farmer's Almanac." Vergil's sources included the Greek natural historians and scientists, such as Aristotle, Eratosthenes, and Aratus, the Latin agricultural treatises of Cato and Varro, and Lucretius' scientific epic De Rerum Natura, as well as his own experiences growing up on a farm. They are a mixture of practical know-how (e.g. how to build a plow), observations of nature, anecdotes (some more dramatic than others, like his description of the effect of the plague on farm animals), and mythology (e.g. Aristaeus' reconstitution of his lost bees — see below). Throughout, Vergil shows his habitual empathy for all things great and small. These qualities can be found in this month's quotation, describing the bees' bedtime.

Vergil the farm boy

Vergil was born in Andes, near Mantua, in a region of northern Italy that was then part of Cisalpine Gaul. Only later, under Caesar, did his province receive Roman citizenship. He was educated at Cremona and Mediolanum (Milan), and later in Rome. His father worked a small farm, which was seized and confiscated in 41 B.C. when Antony was taking farms for redistribution to his soldiers after the Battle of Philippi. (Today, we call this seizing by "eminent domain," the taking of one owner's property to give to another owner for a supposed "public good," an evil that is still with us thanks to a Supreme Court ruling.) Vergil appealed, apparently successfully, to Octavian (the future Emperor Augustus) for an exception for his farm, an incident which he fictionalized in his First Eclogue, where Tityrus keeps his farm, but Meliboeus loses his. Augustus, of course, eventually became Vergil's patron. For the remainder of his life, Vergil lived in Rome and Naples, where, working at his usual slow pace, he spent seven years writing his Georgics.

How to tuck your bees into bed

The Fourth Georgic is about bee-keeping. Much of it is practical, like the advice on where to situate your hives, what kind of trees, rocks, flowers, and running water to provide, how to keep the birds away, and so forth. A conflict between opposing swarms, however, is depicted as a mock-heroic battle. Some of the "facts" described are "old wives' tales" (today we would call such beliefs "urban myths"). For example, he tells how to produce new bees by pulverizing a calf carcass, with skin intact, and leaving it to rot, covered in thyme and other herbs, causing new bees to appear by spontaneous generation. The technique, he says, was first used by the mythical Aristaeus, who lost his bees when cursed for accidentally causing the death of Eurydice. (There is a fascinating account of such beliefs in spontaneus generation of various (usually lower) forms of life, some believed in up to quite recent times, in Eugene S. McCartney, "Spontaneous Generation and Kindred Notions in Antiquity", in Transactions of the American Philological Association Vol. 51 (1920), pp. 101-115, available on the Web.) This month's quotation is closer to reality, concerning the method of persuading bees to go to their hives after a summer day collecting nectar. Sprinkling or "medicating" their resting places (medicatis sedibus) with their favorite herbs, together with the sound of cymbals, will induce them, like pampered children, to "on their own" (ipsae) "tuck themselves into their little cradles" (sese in cunabula condent).

Here, in Latin and English, is Vergil's description of the bees' warm-weather awakening and sleep. Note the reference to "The Mother" (Matris), the Great Mother, Cybele, the Anatolian goddess whose worship included the clashing of cymbals.

Vergil,Georgic 4, vv. 51-66

quod superest, ubi pulsam hiemem Sol aureus egit

|

Vergil's bees in summerFurthermore, when the golden Sun, dispelling winter

|

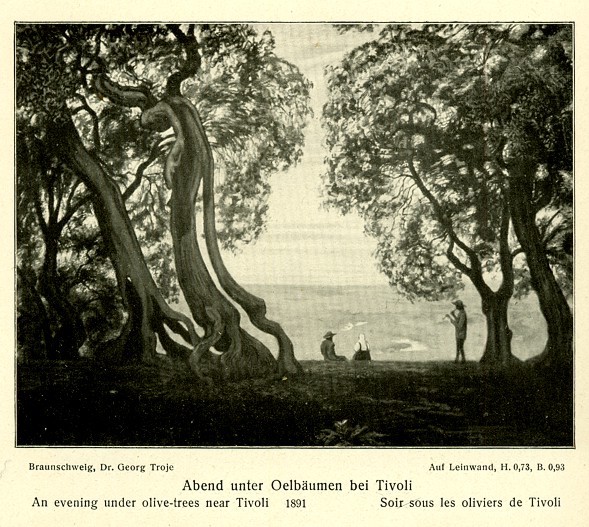

An Italian peasant plays his flute, overlooking a lazy river. (Illustration: painting by Hans Thoma, 1891, from Thoma: Des Meisters Gemälde in 874 Abbildungen, Stuttgart, 1909).

Quotation for July 2010: We have the IPad and Kindle, but what "tablets" did Homer's heroes use? (Bellerophon's cryptic message in the Iliad) |

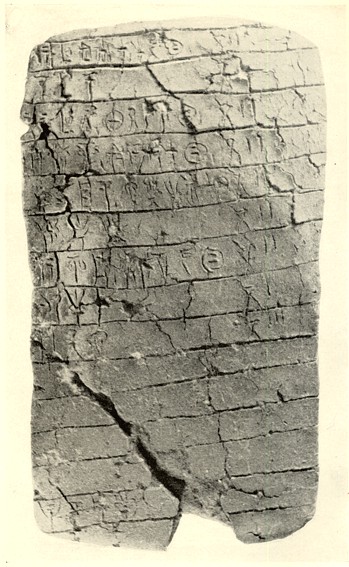

A tablet from Mycenae in Linear B, listing men employed as bakers. (Illustration from Ventris and Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 1959).

From Linear B to the IPad

Tablets! The latest buzz in communications is a portable, rectangular electronic device on which you can read books, magazines, and newspapers, and (on some, at least) exchange pictures, view movies, and play games. Apple's IPad competes with Amazon's Kindle, and Research in Motion, maker of the Blackberry, has announced it will soon market its own version of the tablet. (Who said literacy was dead!) The hand-held, flat, usually rectangular surface is the latest manifestation of one of the oldest objects for communication, expression, and record-keeping. In antiquity, tablets ranged from clay slabs stamped in cuneiform to wooden tablets coated with wax, that could be "erased" and used over and over. Two (or more) of the latter could be fastened together to form a diptuchon deltion or double-folded tablet, precursor of the modern book. Herodotus describes how Demaratus used one of these "books" to send a secret message telling the Spartans that Xerxes was about to invade. He scraped the wax off the surfaces of the tablets, wrote the message on the wood beneath, then replaced the wax, to simulate blank tablets. Only when the wax was removed could the message be read (Herod. 7.239). Even Homer's heroes, it seems, had some form of tablet for recording information. Our quotation of the month is Homer's only apparent mention, in the Iliad, of the use of a tablet bearing some kind of communication.

Breaking news! The Trojan War was real!

It was not so long ago that there was this mental image of Homer, the great poet, sitting at a desk writing his magnificent Iliad and Odyssey, weaving together fictional folk tales of made-up heroes in lands as unreal as Hogwarts Academy. In a little more than one hundred years, this all changed. Homer didn't have writing, but Agamemnon did (sort of). While many scholars and gifted amateurs, in archaeology and philology, have contributed to this field, three insights stand out:

- Mycenae and Troy were real historic places, and the heroes and heroines of the Iliad and Odyssey were undoubtedly (at least based on) real people. Heinrich Schliemann, aided by his Greek wife Sophia, discovered the site of ancient Troy, which he began excavating in 1868. He went on to identify and excavate Mycenae and at the time of his death was about to dig at Knossos, the capital of Minos, later excavated by Sir Arthur Evans.

- Homer didn't "write" his poems at all, but composed them "orally," on the spot

(but someone who could write wrote them down).

The "Homeric Question" of the true authorship of the Homeric poems had raged for

decades (was there one author or many?). Milman Parry's study of South Slavic

traditional poetic composition, begun in 1933, and comparisons with the formulaic

nature of the Homeric poems left no doubt (at least for most people) that the

ancient epic poems were living things, which the bards, like jazz musicians,

recomposed during each "set," making them longer or shorter, depending on the

interests of the audience. Some time, probably in the eighth century B.C.,

someone took down the transcript of a performance (or performances), and

they began to take on the "stuffed and mounted" aspect that they have today.

The music that accompanied them was lost long ago.

Parry died young, but his work was continued by

Albert Lord, who published The Singer of Tales in 1959.

My own contributions to the study of oral poetry in Hesiod

and the Homeric Hymns are available on this Web site:

"Verbal Patterns in Hesiod's Theogony",

Selected Excerpts from the book Traditional Themes and the Homeric Hymns,

"Thought Clusters in Early Greek Oral Poetry". - Agamemnon, Nestor, Odysseus, and the other Homeric kings did have writing (at least their accountants did). It was long believed that the Greeks did not have writing until they adapted the Phoenician alphabet in the ninth or eighth century B.C. But at Mycenae, Knossos, and at Pylos (Nestor's city), many clay tablets were found with strange forms of writing, known as "Linear A" and "Linear B." Linear A, only partially deciphered, is apparently a non-Greek "Minoan" language. The cryptographic and code-breaking activities of many persons, leading up to the decipherment of Linear B, involving matrices of matching sounds and word endings, cannot be detailed here, but it was Michael Ventris who "broke the code" in 1952, proving that Linear B was Greek, written in a syllabary where each character represents not a simple letter but an entire syllable. No poetry or other literature has been found in Linear B, only records of commodities, military supplies, personnel—the workings of palace bureaucracy. Ventris, too, died young, but his work was published in Michael Ventris and John Chadwick, Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 1959. A typical tablet from Mycenae is illustrated above.

The Homeric poems themselves, though in their final composition the product of a culture that had writing, and describing a society that had writing, nowhere mention writing, except in one unusual passage in Iliad Book 6, in the story of Bellerophon, whose death warrant was contained in the "baneful symbols" of a "folded tablet." Was this an anachronism from Homer's own time, or an echo of a remembrance from the time of Homer's heroes?

Bellerophon, Anteia, and Pegasus

In Iliad Book 6, the Lycian Glaucus is telling Diomedes his ancestry, which includes the hero Bellerophon. Beautiful and manly, Bellerophon caught the eye of Anteia, the wife of Argive king Proetus (in some versions, she is called Sthenoboea), who wanted to make love to him. He refused, and she took revenge by telling her husband that Bellerophon had tried to seduce her. (If this sounds familiar, the same story was told of Hippolytus and Phaedra.) Proetus does not kill Bellerophon, but sends him to Anteia's father, the king of Lycia, carrying a "folded tablet" (pinaki ptuktô) bearing "baneful symbols" (sêmata lugra), which turn out to be a request that the king of Lycia kill Bellerophon. He doesn't kill him, either, but sends him on various suicide missions (which he instead accomplishes), including killing the Chimaera, a monster one third lion, one third snake, one third goat (chimaira); the "glorious" Solymoi; and the Amazons. (In some versions, Bellerophon accomplishes his tasks mounted on the winged horse Pegasus. Sources include Hesiod (Theogony 325), who also gives the Chimaera three heads, one for each of her species.) Since Bellerophon seems unkillable, the king of Lycia decides that he is the offspring of a god and gives him his daughter in marriage and a big estate. Later however, he became "hated of all the gods" and was killed by them. In some versions, the reason was that he tried to fly Pegasus up to heaven.

Below is the story of Bellerophon and Anteia from Iliad Book 6.

Anteia's plot against BellerophonThe wife of Proetus, lovely Anteia, was mad for Bellerophon, — Iliad, Book 6, vv. 160-186 |

Bellerophon and Pegasus. (Illustration from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

Quotation for June 2010: A commentary on the oil spill: If you go too deep or too high, the gods will get even (Otus and Ephialtes storm Olympus) |

Challenging the boundaries of Nature

The disastrous oil spill, that never-ending nightmare in the Gulf of Mexico, reminds us once more that when we challenge the boundaries of Nature without thought for the implications of our deed, the gods get angry. Hubris breeds carelessness—we cut corners before, and nothing happened. We think of the Exxon Valdez oil spill, in retrospect a smaller disaster in that the ship carried a known, finite amount of oil. We think of the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, its very name a reminder of its purpose to dare fate. Hubris also breeds a stubborn risk-taking, a reliance on untested methods. The wax that melted in Icarus' wings when he flew too close to the sun was a new technology, untested under extreme conditions, a fact understood by his father Daedalus, who designed them. But after all, the two were in a colossal hurry to get away from King Minos and his Minotaur!

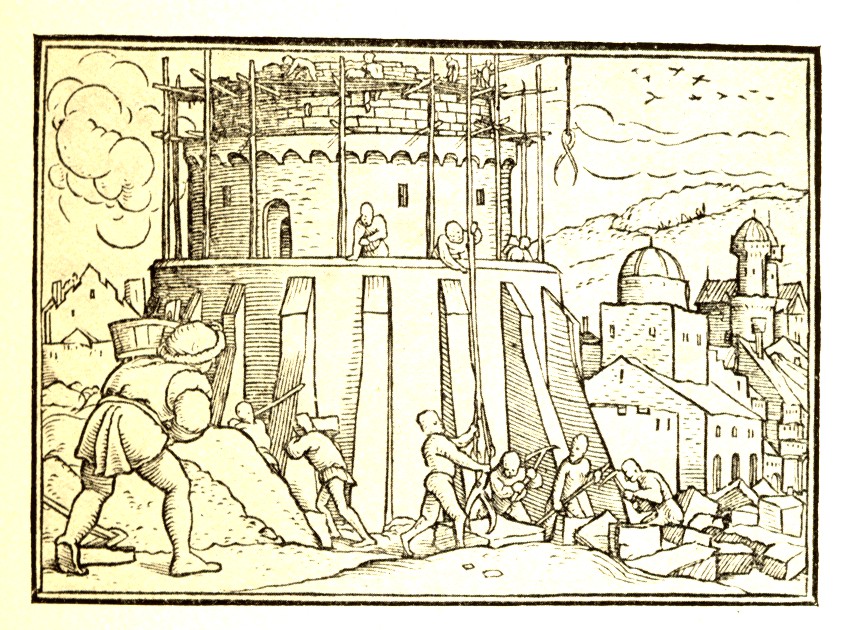

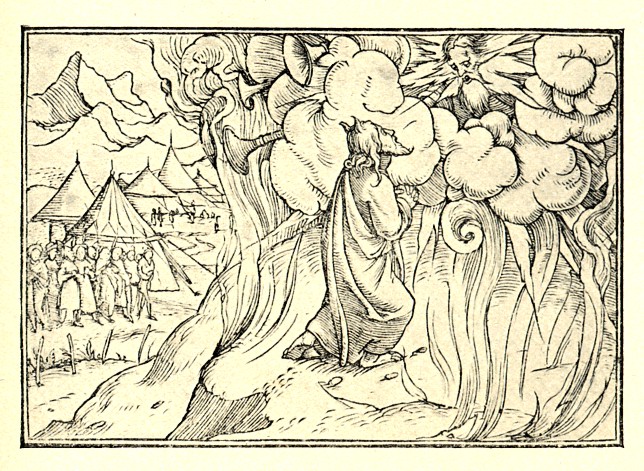

A parallel often invoked is mad Captain Ahab's pursuit of the white whale Moby Dick. Just as the oilmen (and women) of BP, Chevron, Shell, et al. drill deeper and deeper, farther and farther from shore, the whalers of Melville's time were forced to sail farther and farther in search of whales and their oil, the petroleum of their day, used for lighting, fuel, and lubrication. For a striving toward the sky, we could mention the Tower of Babel, whose top was to reach the Heavens. God sowed confusion among its builders by causing them to all speak different languages. But the Classical example that immediately occurred to the author of this page was the attempt by the giants Otus and Ephialtes to reach the kingdom of the gods by piling the mountains Pelion and Ossa on Mount Olympus.

Otus and Ephialtes: Piling Pelion on Ossa on Olympus

Mount Olympus, at 9600 feet, is the tallest mountain in Greece, situated on the border of Macedonia and Thessaly. It was regarded as the home of the gods. With Mounts Pelion and Ossa, it forms a chain along the east coast of northern Greece, and is separated from Mount Ossa by the valley of Tempe, through which the Peneus River flows. Mount Pelion was the location of the cave of Chiron, the wise centaur who was the tutor of such heroes as Jason and Achilles, and of the hero-physician Asclepius. It was on Mount Pelion that the marriage took place between Peleus and the sea-nymph Thetis, parents of Achilles. At that wedding, the goddess Eris ("Strife") threw the golden apple that sparked the Judgment of Paris that was the cause of the Trojan War, when Paris judged Aphrodite the fairest of the goddesses, and she gave him Helen in return. In the vale of Tempe, between Ossa and Olympus, Daphne, daughter of the river god, prayed (successfully) to her father to turn her into a laurel tree when she was pursued by Apollo, who was in love with her (see the quotation of the month for April 2007).

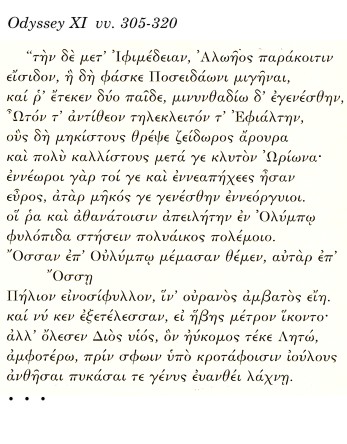

Otus and Ephialtes were the giant sons of Iphimedeia, wife of Aloeus, by Poseidon. By the time they were nine years old, they were each thirty-six feet wide and fifty-four feet tall. There are different versions of the story, but the gist of the most common legend is that the brothers attempted to pile the three mountains, Pelion, Ossa, and Olympus on top of each other so that they could reach heaven (their motivation differs with the version). They were stopped by the gods before they could carry out their plan. Homer tells the story in Odyssey Book 11, Odysseus' Journey to the Underworld (see the quotation of the month for Halloween, October, 2009). In the Land of the Dead, Odysseus meets, among many others, the ghosts of famous women, including the giants' mother, Iphimedeia. In Homer, the brothers were killed by Apollo. Olympus is normally the home of the gods, but in this mountain-sandwich it is on the bottom, and the gods are somewhere above, in the ouranos, the sky or heaven.

Below is the description in Odyssey Book 11.

|

|

Otus and EphialtesAfter [Leda], I beheld Iphimedeia, wife of Aloeus, |

The Tower of Babel, woodcut by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1538. (From Hans Holbein the Younger: His Old Testament Illustrations, Dance of Death, and Other Woodcuts, New York, before 1917.)

Quotation for May 2010: Gerrymandering for a good cause: The reforms of Cleisthenes vs. entrenched special interests (Aristotle's Constitution of Athens) |

Entrenched special interests, then and now

In present-day Greece, the United States, and other democracies, political gridlock results from conflicts between entrenched special interests: powerful corporations; labor unions; wealthy politically-connected families (in the U.S. these were once dominated by Roosevelts and Rockefellers; today more apt examples might be the Kennedys and Bushes). Big banks are pitted against community activists; developers against environmentalists; urban and suburban versus rural; hard right against hard left. In the U.S two-party system, both Democrats and Republicans once functioned as de facto coalitions, with each party having both a liberal or left wing and a conservative or right wing. Democrats included big-city leftists and Southern conservatives. Republicans had big money from Wall Street but also blue-collar householders from Southern California. Some well-known members of the parties could be both liberal and conservative at the same time, like Senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson of Washington State (d. 1983), who was liberal on social welfare and environmental issues, but conservative on military matters, supporting the Vietnam War and becoming known as the "Senator from Boeing" for his backing of the company headquartered in his state. Today, both parties have purged unbelievers and heretics, hardening into the hard-line ultra-liberal Democratic and hard-line ultra-conservative Republican camps.

One of the methods used by parties to hang onto power is the "gerrymander," a congressional (or other political) district, often of strange shape, so drawn that it contains, say, all Republicans, making it a "safe" district that can reliably be counted on to always vote the same way — thus again and again returning the same congressperson to the legislature. Perhaps we could take some advice from the great Athenian lawgiver Cleisthenes.

Cleisthenes (6th cent. B.C.) is often mentioned glibly as the "founder of Athenian democracy" or listed among great statesmen along with Washington and Jefferson, but what did he actually do?

Draco, Solon, and Cleisthenes

The oldest council at Athens was the Council of the Areopagus (he boulê he ex Areiou pagou, "the council from [that meets on] Ares' Hill"), dating from the early days of the Athenian kings. Made up of ex-archons, it was in its earliest form the king's advisory board, and also had special jurisdiction over homicide. The archons (magistrates) themselves were chosen from among the wealthy or nobility. By the seventh century B.C., however, the archons were elected by the people. Athens' first written laws were drawn up by Draco (621 B.C.). While most of Draco's laws had to do with the system of elected offices, he is most famous for the fact that he made death the sentence for most crimes, hence the term draconian punishment! Solon (c. 640-c.560 B.C.) was the next great lawgiver. The rich were still in control, and the poor, if unable to pay their debts, could be enslaved. In the ensuing civil strife, Solon was asked to become mediator and Archon. He cancelled all existing debts and mortgages, and prohibited debts secured by the debtor's own person. These reforms were called the Seisachtheia or "shaking off of burdens" (from seiô "shake" and achthos "burden"). Solon celebrated his own actions in verse, fragments of which are still extant. (The word "solon" survives in English as a semi-humorous synonym for "lawgiver.") Unfortunately, Solon's constitution left too much power in the hands of the old Ionic tribes and the aristocratic clans. After a period of discord, Athens was ruled by the tyrant (i.e. dictator) Pisistratus (d. 527 B.C.) and his sons Hippias and Hipparchus. Emerging from tyranny, the Athenians chose Cleisthenes as their leader. Cleisthenes, himself a member of one of the most famous and powerful families, the Alcmaeonids (to which Pericles was also related), created the ultimate form of the Athenian democracy, cutting across and disrupting clan, tribe, and regional monopolies.

Attica, comprising Athens and its surrounding district, consisted of between one and two hundred small districts called "demes." Cleisthenes divided Attica into three major regions: the city, the coast, and the inland region. Within each region, he divided the demes into ten groups called trittyes, so that there were thirty such trittyes in all. From the thirty trittyes he formed ten groups of three, but no group could contain two trittyes from the same region. Each of these groups became a new "tribe," replacing the old hereditary tribes. The new tribes were given names of eponymous heroes, chosen by the Delphic oracle. This mix-and-match method at one blow destroyed the influence of tribes, clans, regions, and parties. Where "gerrymandering" creates odd political entities linking districts for the purpose of concentrating power, Cleisthenes' reforms created political entities crossing geographical boundaries for the sake of breaking up power.

The most important source for the reforms of Cleisthenes is the Constitution of Athens (Athenaion Politeia) of Aristotle, from which we quote below. Known about but only rediscovered in the nineteenth century, it was originally one of a series of city-state constitutions compiled by Aristotle (probably with the help of his students).

Gerrymanders

The term "gerrymander" has its origin in the governorship of Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts, who in 1812 signed into law a redistricting plan that created an oddly-shaped congressional district of non-contiguous (or barely contiguous) towns, whose purpose was to maximize the votes for his party, the Democrat-Republicans, by lumping most of the opposition, the Federalists, into one humungous district, leaving the Democrat-Republicans in the majority in the other districts. Enemies of the plan likened the shape of the resulting district to a salamander, prompting the Boston Gazette of March 26, 1812 to publish the cartoon depicted below. (Governor Gerry, by the way, pronounced his name with a hard "g," as in "Gary," not with the soft "g" as in "Jerry," normally used when pronouncing his namesake term.)

The anti-gerrymander

What Cleisthenes created was a kind of "anti-gerrymander," in which similar political interests are not lumped into one unit, but each unit is purposely drawn to include several different interest groups. If such a scheme were carried out in the United States, it might work as follows (OK, this is somewhat tongue in cheek, not to be taken too seriously, but it illustrates the idea): The U.S. would be divided into three areas: East coast; Central states; West coast. (Of course, the country, being large, has more than three sections; the South, in particular, really shouldn't be lumped with the others, but we are keeping the Cleisthenic model). Then new administrative units would be formed, each including counties from each region. One unit might contain a set of counties from Massachusetts and Connecticut, another set from Iowa and Nebraska, and a third set from California and Nevada. The name of this particular unit could be called the "Benjamin Franklin," the name having been chosen from a list of national heroes by a computer, the closest thing we have to an oracle!

Aeschylus and the Areopagus

The Council of the Areopagus, as a holdover from the old days of kingship at Athens, was held in sentimental reverence by conservative Athenians. Aeschylus, in his Oresteia, gives a tip of the hat to this old, aristocratic institution. Orestes, pursued by the Furies after killing his mother Clytaemnestra, ends up being defended against a charge of matricide by Athena as his defense lawyer (and tying vote) before the Areopagus, which acquits him.

Below, in Kenyon's translation, is the description of Cleisthenes' reforms in Aristotle's Constitution of Athens.

Reforms of CleisthenesThe people, therefore, had good reason to place confidence in Cleisthenes. Accordingly, now that he was the popular leader, three years after the expulsion of the tyrants, in the archonship of Isagoras, his first step was to distribute the whole population into ten tribes in place of the existing four, with the object of intermixing the members of the different tribes, and so securing that more persons might have a share in the franchise. From this arose the saying 'Do not look at the tribes', addressed to those who wished to scrutinize the lists of the old families. Next he made the Council to consist of five hundred members instead of four hundred, each tribe now contributing fifty, whereas formerly each had sent a hundred. The reason why he did not organize the people into twelve tribes was that he might not have to use the existing division into trittyes; for the four tribes had twelve trittyes, so that he would not have achieved his object of redistributing the population in fresh combinations. Further, he divided the country into thirty groups of demes, ten from the districts about the city, ten from the coast, and ten from the interior. These he called trittyes; and he assigned three of them by lot to each tribe, in such a way that each should have one portion in each of these three localities. All who lived in any given deme he declared fellow-demesmen, to the end that the new citizens might not be exposed by the habitual use of family names, but that men might be officially described by the names of their demes; and accordingly it is by the names of their demes that the Athenians speak of one another. He also instituted Demarchs, who had the same duties as the previously existing Naucrari, -- the demes being made to take the place of the naucraries. He gave names to the demes, some from the localities to which they belonged, some from the persons who founded them, since some of the areas no longer corresponded to localities possessing names. On the other hand he allowed every one to retain his family and clan and religious rites according to ancestral custom. The names given to the tribes were the ten which the Pythia appointed out of the hundred selected national heroes. — Aristotle, Constitution of Athens Book 3, Part 21, translated by Sir Frederic G. Kenyon. |

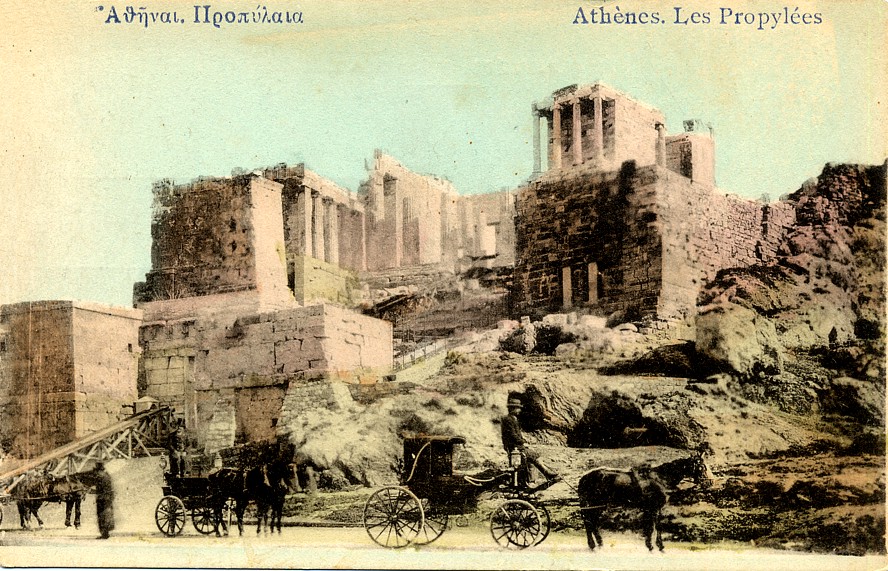

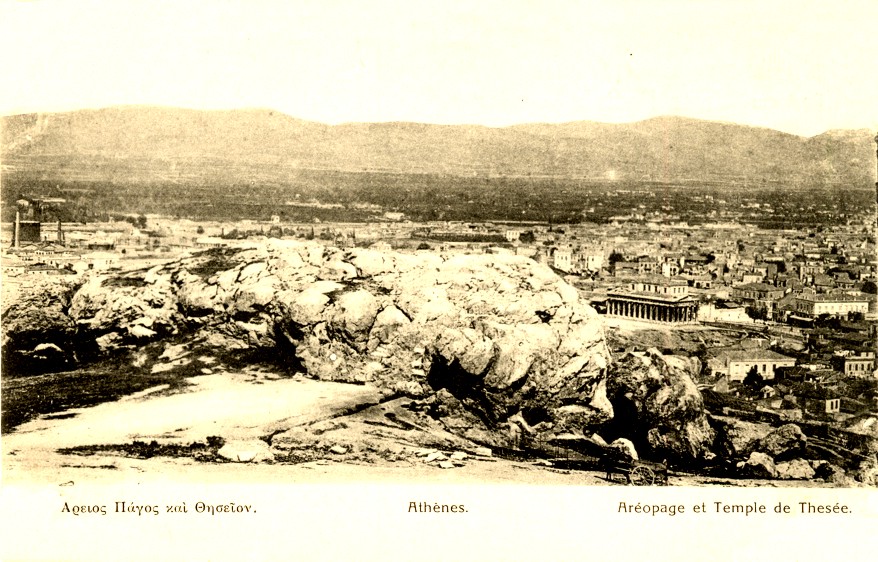

View from the hill of the Areopagus ("Ares' Hill"), from a pre-1907 postcard. It was on this hill that the Council of the Areopagus met.

Quotation for April 2010: For Arbor Day and Earth Day, Aphrodite entrusts the baby Aeneas to the tree nymphs (Homeric Hymn V to Aphrodite) |

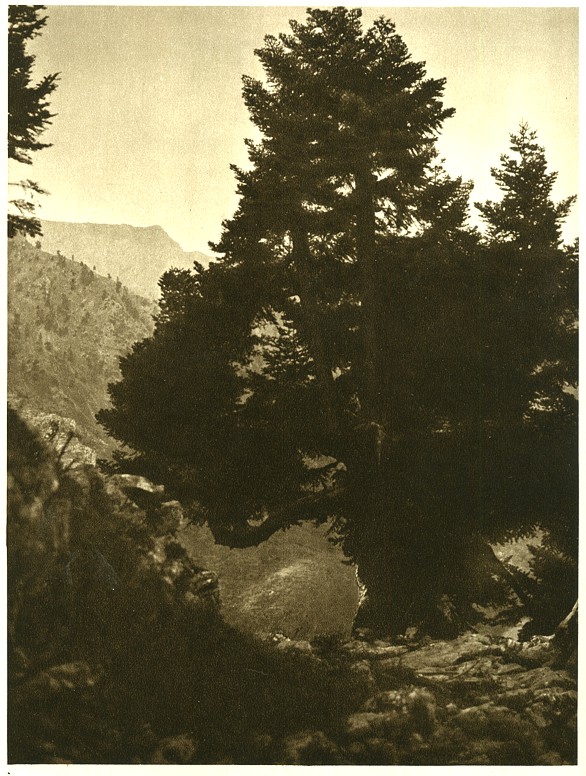

Pine tree on Mount Erymanthus, in the Peloponnesus (where Heracles chased the Erymanthian Boar). Illustration from Hanns Holdt, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Griechenland, 3rd edition, 1928.

Arbor Day and Earth Day

In April, we celebrate two environmental holidays, Earth Day (April 22) and Arbor Day (the last Friday in April, falling this year on April 30). Earth Day was founded in 1970 to honor our Blue Planet and promote preservation of its environment. The much older National Arbor Day, founded in 1872, encourages the growing of trees, both for their usefulness — for shade and windbreaks, to hold the soil, for fuel and building materials — and for their aesthetic value. For our quotation of the month, we honor tree nymphs (also called "dryads," from drus, "tree," especially oak.)

Aphrodite and Anchises' secret love child

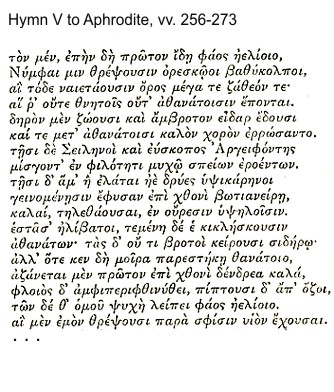

In the Homeric Hymn V to Aphrodite, Aphrodite, goddess of fertility and sex, who makes everybody else fall in love, is given a dose of her own medicine by Zeus, who makes her fall in love with the Trojan prince Anchises, who is tending herds on Mount Ida, near Troy. (See the February Quotation of the Month, "Greek goddesses as ancient "cougars.") Pregnant by him with the future hero Aeneas, Aphrodite makes Anchises promise never to divulge her secret shame (a secret that was obviously not kept, or we would never have Vergil's Aeneid). She will hand the child over to the tree-nymphs of the mountain to raise until the age of five, at which time she will bring him to his father. Anchises is to say only that the mother is a mountain-nymph; otherwise, Zeus will strike Anchises with a thunderbolt. The nymphs are neither mortal nor immortal, as they live and die with their trees, but they can live long lives. (Think how old the nymph of a California redwood must be (more than 2000 years!), or the nymph of a bristlecone pine — almost 5000 years! The bristlecone nymph was ancient when the Hymn to Aphrodite was composed circa 750 B.C. and she's still going strong!) Below, in Greek and English, is Aphrodite's description of the nymphs. The Sileni, similar to satyrs, were shaggy, randy forest spirits, often portrayed with horses' ears and legs. The "slayer of Argus" is Hermes.

|

|

Life and death of a dryad

When indeed the child first sees the light of the sun, |

A Dryad, from an old engraving.

Quotation for March 2010: Happy Exelauno Day! (March Fo(u)rth). The March of the Ten Thousand Greeks (Xenophon's Anabasis) |

Great bustard (Otis tarda), one of a number of species of bustard, belonging to the family Otididae, large birds related to cranes, which live in dry grasslands of the Old World. Bustards were among the wild game hunted by the Ten Thousand Greeks on their trek across Asia Minor and back. The word "bustard" is from the Latin avis tarda, "slow bird." The Greek word for "bustard" is ôtis. Today, they are threatened by overhunting and loss of habitat. (Images from Wikipedia: (left) from a 1905 German Encyclopedia, (right) Great Bustard at the Beijing Zoo, June 2008, author Wadofglue.)

Ten thousand Greeks march forth

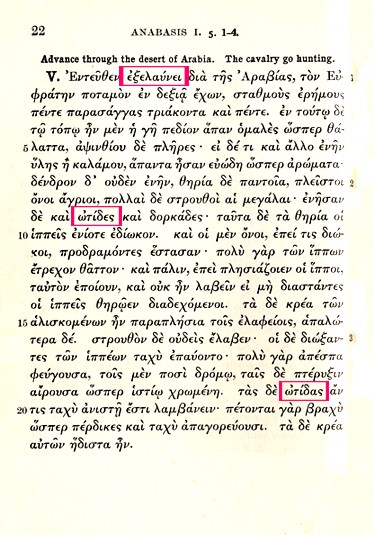

For students of elementary Greek, Xenophon's Anabasis, the account of ten thousand Greek mercenaries who fought their way out of Asia Minor after the death of their employer, Cyrus the Younger, has long been a familiar text. Its simple, straightforward language (like that of Caesar's Gallic Wars in Latin) made it for many years the first Greek text to which many students were exposed. The language is repetitive, as the men march across one desert and mountain after another. Perhaps its most characteristic verb is exelauno, "I march forth." Therefore, generations of students of Greek have celebrated March Fourth as Exelauno Day!

The ill-fated campaign of Cyrus the Younger

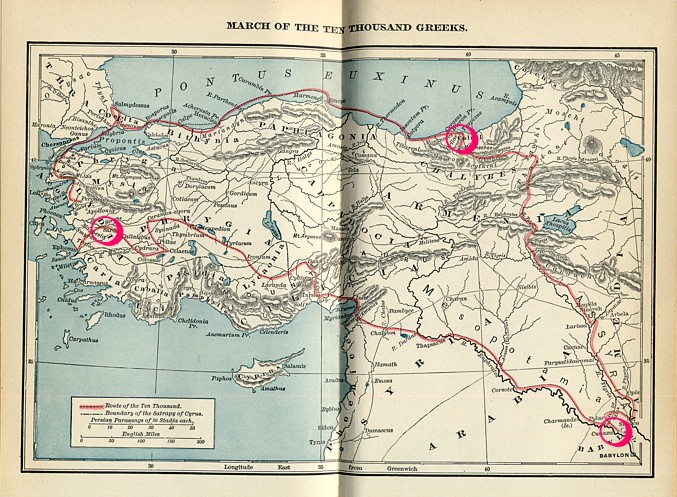

In 401 B.C., Cyrus the Younger attempted to take the throne from his older brother, Artaxerxes II, king of Persia. To aid his Persian troops, he enlisted an army of about 13,000 Greek mercenaries, of whom 10,600 were hoplites (heavy-armed foot soldiers), under the Spartan Clearchus. They mustered at Sardis, inland from the central coast of today's Turkey. In the summer of 401, taking a southerly route, they encountered Artaxerxes' army at Cunaxa, in Babylonia, near what is today Baghdad in Iraq. The Greeks prevailed, but Cyrus was killed, and Clearchus and the other Greek senior officers, lured by a phony offer of a treaty by the Persian commander Tissaphernes, were all executed. Cyrus' Asiatic troops fled, but the Greek soldiers decided to fight their way back rather than surrender. Xenophon, a pupil of Socrates who was a volunteer in the expedition but was neither general nor professional soldier, took charge. Being elected general by the troops, he led them through hostile territory, over desert and mountain, until they reached the coast at Trapezus, on the Black Sea. The cry of the vanguard as they topped the last mountain (described by Xenophon in his Anabasis, "The Trek Up-country"), Thalatta, thalatta! "The sea, the sea!" is iconic.

The quotation below, in Greek and English, is a typical passage. It comes in the first part of the trip, while the Greeks are accompanying Cyrus. Marked in red are the words exelaunei ("he marches") and ôtides(-as) "bustards", the birds pictured above. The text is from the edition of the first four books of Xenophon's Anabasis by Goodwin and White, 1894. Stathmoi were stages or resting places on the royal Persian road, hence, generally, a day's march. A parasang (Persian farsang) was about thirty stadia, a stade being 600 Greek feet, or 582 feet 6 inches English, hence a little over three miles.

|

|

A hunting trip in the desert:From there, he [Cyrus] marches forth through Arabia, keeping the Euphrates River on the right, five desert stages, thirty-five parasangs. In this region, the land was a plain, entirely flat like the sea, full of absinthe plants. Anything else that there was of brushwood or reeds, was all sweet-smelling like aromatic spices. Not a tree was there, but there were all kinds of wild game — wild asses in greatest number, and many ostriches. There were also bustards and antelope. The cavalry sometimes chased these animals. The asses, if someone chased them, would run ahead and stand still, for they ran much faster than the horses. Again and again, as soon as the horses got close, they did the same thing, and it was not possible to catch them unless the horsemen, placing themselves at intervals, hunted them in relays. The meat from those that were captured was similar to venison, but more tender. Nobody caught an ostrich. Horsemen who gave chase quickly stopped, for it withdrew quickly as it ran away, using its feet to run, and its lifted wings like a sail. It is possible to catch the bustards if one starts them suddenly. For they fly a short distance, like partridges, and quickly grow weary. Their meat was the sweetest. |

Map of the march of the Ten Thousand. (Source: the edition of the first four books of Xenophon's Anabasis by Goodwin and White, 1894.) The red line indicates their route, while the red circles (added for this Web site) mark the important points: Sardis (inland from Ephesus), where the troops muster, Cunaxa, near Babylon, where Cyrus was killed (and the Greeks began their departure), and Trapezus, on the Black Sea, where they finally reached the shore.

Quotation for February 2010: Inspired by Valentine's Day, Greek goddesses as ancient "cougars" (Homeric Hymn V) |

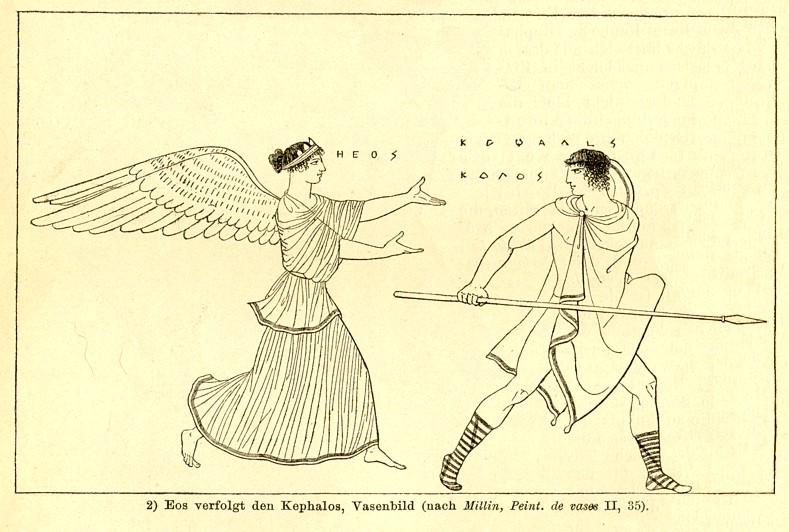

Eos in hot pursuit of Cephalus, in a vase painting (image from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890).

Ancient goddesses as "cougars"

Greek goddesses were the original "cougars," ageless beauties who chase after young, attractive men. Odysseus encountered two of them, Calypso and Circe, both of whom seduced him and wanted him to stay with them forever (Odyssey Books 5 and 10). Calypso, ordered by the gods (in a message brought by Hermes) to turn Odysseus loose, laments the ill fortune such affairs may bring. She tells how Eos, goddess of the dawn, seduced the giant hunter Orion; he was subsequently struck down by Artemis' arrows. (But we know that later he became the constellation Orion.) She tells how Demeter, goddess of the grain "lay with Iasion in a thrice-plowed fallow field" (an obvious fertility myth); Iasion was smitten by Zeus' thunderbolt.

Eos was particularly amorous, being associated in mythology with a succession of lovers, including Cephalus (see the pictures above and below) and the Trojan prince Tithonus, whose story is included in the Homeric Hymn V to Aphrodite.

Aphrodite is caught by her own tricks

The Hymn to Aphrodite tells the tale of Aphrodite's seduction of another Trojan prince, Anchises. Aphrodite, goddess of desire, makes gods, mortals, animals, birds, and the creatures of the sea fall in love. Only three are immune to her powers: Athena, Artemis, and Hestia, goddess of the hearth. Zeus, of course, has fallen in love with mortal women many times. Zeus decides to give Aphrodite a taste of her own medicine by making her fall in love with Anchises, who is tending the herds. There is a delightful scene in which Aphrodite, disguised as a Phrygian princess in gold-trimmed attire and smelling of sweet perfume, wafts over mountains and woods, trailing pheromones of love that make all the animals mate madly as she goes. She seduces Anchises, who is horrified when he finds that she is a goddess, for he knows what has happened to other men who slept with goddesses. She understands his qualms, and tells the stories of other Trojan princes carried off by deities, Ganymede, stolen by Zeus to be his cup-bearer, and Tithonus, abducted by Eos.

Eos fell in love with Tithonus, and the two lived rapturously together. Eos asked Zeus to give Tithonus eternal life, but forgot to ask for eternal youth. He withered away in her chamber, forever helpless and babbling. Other myths tell us that he became a cricket, eternally chirping. While sadness came to Eos and Tithonus, they were the parents of a mighty hero. The son of Eos and Tithonus was Memnon, king of the Ethiopians, subject of a lost epic, the Aithiopis.

The birth of Aeneas

Aphrodite assures Anchises that no bad fate awaits him, nor will she try to make him immortal. He, too, will by the father of a mighty son. That son is, of course, Aeneas, a Trojan hero in the Iliad. He was to become even more famous later as the hero of Vergil's epic, the Aeneid, where Aphrodite is known by her Roman name, Venus.

Here, in translation, is Aphrodite's telling of the story of Eos and Tithonus:

Just so did golden-throned Eos snatch away Tithonus, |

Another interpretation of Eos and Cephalus, in terracotta (image adapted from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie.) In this version, Eos is not so attractive (more maternal?), but Cephalus looks rather contented (or is he just surprised?).

Quotation for January 2010: For Martin Luther King, a prophetic dream (in Vergil's Aeneid) |

The Cumaean Sibyl, depicted by Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel. In Vergil's Aeneid, she directs Aeneas to the entrance to the Underworld. She is an old woman, because Apollo, while giving her immensely long life, punished her rejection of him by not granting her eternal youth.

Dreams of a promised future

In January, we celebrated Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s birthday, and February is Black History Month. King's two most famous speeches, the "I Have a Dream" speech of August 1963 and "I've Been to the Mountain Top," delivered in 1968 the night before his assassination, bracket his national fame. In the former, the "dream" was not a sleeping fantasy but a prophecy, not only for Black people, but for the country itself:

"...I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: 'We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal..."

In the latter address, he cast himself prophetically as Moses, looking from Mount Nebo upon the land that will be Israel, which he will never reach:

"...I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land..."

Prophecies of a great nation

The prophetic dream, of course, has a long history. Dreams (the sleeping kind) were important in divining one's course of action. Among famous examples were the dreams of visitors to the sanctuaries of Asclepius, which dictated the course of treatment for the ill. This month's quotation is from the sixth book of Vergil's Aeneid, in which Aeneas, going to the Underworld, learns of his future life, as well as the future greatness of Rome, which will be founded and enriched by his descendants, but which he will never see. This, also, is not strictly speaking, a dream, except for its curious ending. It is modeled on two different episodes in Homer's Odyssey.

Aeneas and Odysseus

The principal model for Aeneas' visit to the Underworld is Odysseus' adventure in the Land of the Dead in Book 11 of Homer's Odyssey. Odysseus, following directions from the goddess Circe, visits Hades' realm to inquire of the spirit of the great seer Teiresias what his future will be. While there, he first meets the shade of his comrade Elpenor, who, having fallen fatally from a roof, was yet unburied. He meets the ghost of his mother, who tells him of the havoc caused by the suitors of his wife Penelope. He meets the ghosts of fellow warriors, like Achilles and Ajax, heroes like Heracles, as well as nameless, wandering wraiths of no renown. Fearing that Persephone will send up the dread Gorgon, Odysseus departs in haste. In Aeneas' case, the role of Circe is filled by the Cumaean Sibyl, whose cave at Cumae (probably the wrong one!) is still pointed out as the place where she gave her prophecies. Aeneas soon meets the ghost of his helmsman Palinurus, who had likewise died in an accidental fall, from the stern of his ship. He meets his former lover, the Carthaginian queen Dido, who, abandoned by him, comitted suicide. Like Odysseus, he meets former friends and enemies, and figures from the mythic past. But in a departure from Homer, Aeneas, guided by the ghost of his father Anchises (filling a role similar to that of Teiresias) sees spirits about to be reincarnated — as Roman heroes of a glorious empire that is to come, not in Aeneas' own lifetime, but in the future! In the most poignant passage, Vergil interpolates a figure from the Emperor Augustus' own circle, Marcellus, son of his sister Octavia and his intended heir, tragically dead at the age of 20. What an impact this must have had, as Vergil recited his poem to the emperor and his family!

Gate of horn, gate of ivory

Aeneas' departure from the Underworld abruptly changes to the language of dreams, although this visit was not depicted as a dream. There are, says Vergil, two gates of Sleep, a gate of horn, through which true dreams emerge, and a gate of ivory, through which false dreams pass. Aeneas comes out though the gate of ivory. Why? This passage is lifted from Book 19 of the Odyssey, in which Penelope tells the returning Odysseus (whom she still does not trust to really be her husband) of her doubts concerning a prophetic dream she had of his return. In Greek the words make a pun. Dreams proceeding from the gate of "horn" (keras) are fulfilled (krainousi), but those from the gate of "ivory" (elephas) deceive (elephairontai). Why did Aeneas depart from the gate of ivory? Many theories are proposed, including a suggestion that because false dreams were thought to occur before midnight and true dreams after midnight, the gate of horn wasn't yet open. But why would he be in such a hurry? Perhaps, because these events are still, for Aeneas, in the future, they are for him just a dream, not reality?

Below, in translation, are the final lines of Aeneid Book 6. Young Marcellus is seen walking beside an older hero, also named Marcellus:

But Aeneas said, for he saw walking beside [the older Marcellus] |

"Moses on Mount Sinai," woodcut by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543). Moses ascended one mountain, Sinai, to receive the Ten Commandments. At the end of his life, he ascends Mount Nebo, from which he looks down on the promised land that he will never reach.

---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2009 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: