These are quotations for the year 2013. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2013, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2013 |

Below are quotations for the year 2013. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2013

Click on a link to read each quotation

2013

- December, 2013; For the Winter Holidays, a mediaeval Latin song of festivity.

- November, 2013: Celebrating a new tunnel under the Bosporus and the journey of Io, the maiden turned into a cow (Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 721-735).

- October, 2013: For Halloween, the Pumpkinification of Claudius, by Seneca.

- September, 2013: For the grape harvest of early fall, a selection from Book II of Vergil's Georgics.

- August, 2013: For the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington: Cicero on the meaning of freedom (in Paradoxa Stoicorum).

- July, 2013: Inspired by the NSA spying case: A surveillance scandal: how Hadrian spied on the private lives of his soldiers.

- June, 2013: Woman Power! Cynisca from Sparta wins the Olympic four-horse chariot race (396 and 392 B.C.).

- May, 2013: For Memorial Day, the funeral of Achilles, as described in Odyssey Book 24.

- April, 2013: For the opening of a Presidential Library, Horace declares his poetry more lasting than the pyramids.

- March, 2013: Springtime is growing season, as described in Hesiod's Works and Days 448-492.

- February, 2013: for Valentine's Day, Eros plays tag with the Spartan poet Alcman.

- January, 2013: Does the presence of weapons itself inspire violence? (Odyssey 19.1-13 (and 16.284-294).

Quotation for December, 2013

For the Winter Holidays, a mediaeval Latin song of festivity |

It's winter, but can spring be far behind? The illustration depicts an early twentieth century concept of an ancient Roman festival. Illustration from M.L. [Minnie Louise] Smith, Elementary Latin, 1920 edition.

Happy Winter Holidays!

Merry Christmas, Happy New Year, Happy Hanukkah, Happy Kwanzaa, Happy Winter Solstice! This month we celebrate the winter holidays. Let us wish for peace in the world.

A mediaeval Latin song

Our Quotation of the Month is a mediaeval Latin song Dies Festus Hodie. ("Today's a Holiday"). The text is from the Carmina Burana, the collection of mediaeval songs (ca. 1230), a number of which were made famous in their arrangements by Carl Orff in the twentieth century. But his was not the only setting.

At the end of Smith's Elementary Latin, from which the picture at the head of this month's column is taken, are a number of Latin songs (including, of course, Gaudeamus Igitur), with music for each one. One of these is a version of Dies Festus attributed to Carl Maria von Weber. As printed in Smith, the Weber setting, shown immediately below, omits some lines pertaining to emotions and bodily gestures. However, the text I have chosen to translate, available from the online site of the Bibliotheca Augustana in Augsburg, Germany, includes the missing lines.

Note that the term [dies] ferialis, which in Classical Latin would mean "feast day," by the Middle Ages had come to mean a "free day," or "week day" (other than Saturday and Sunday). "Naso" is the poet Ovid (Publius Ovidius Naso).

Carmina Burana 216Tempus hoc laetitiae,dies festus hodie! omnes debent psallere et cantilenas promere et affectu pectoris et toto gestu corporis et scolares maxime, qui festa colunt optime. Stilus nam et tabulae sunt feriales epulae et Nasonis carmina vel aliorum pagina. Quicquid agant alii, iuvenes amemus et cum turba plurium ludum celebremus! |

Time to celebrate!Now is the time for joy,today is a holiday! All should play the harp and shout out songs, with emotion of the heart and every gesture of the body, students most of all, who best observe the holidays. The stylus and the tablet are the banquets of the weekday, the poems of Naso or the pages of other writers. Whatever others may do, let us young people be in love, and with the biggest crowd, let us celebrate the merrymaking! |

A mediaeval harp. Upon this the students are encouraged to "psallere" as they sing their "cantilenas."

Quotation for November, 2013

Celebrating a new tunnel under the Bosporus and the journey of Io, the maiden turned into a cow (Aeschylus, Pronetheus Bound) |

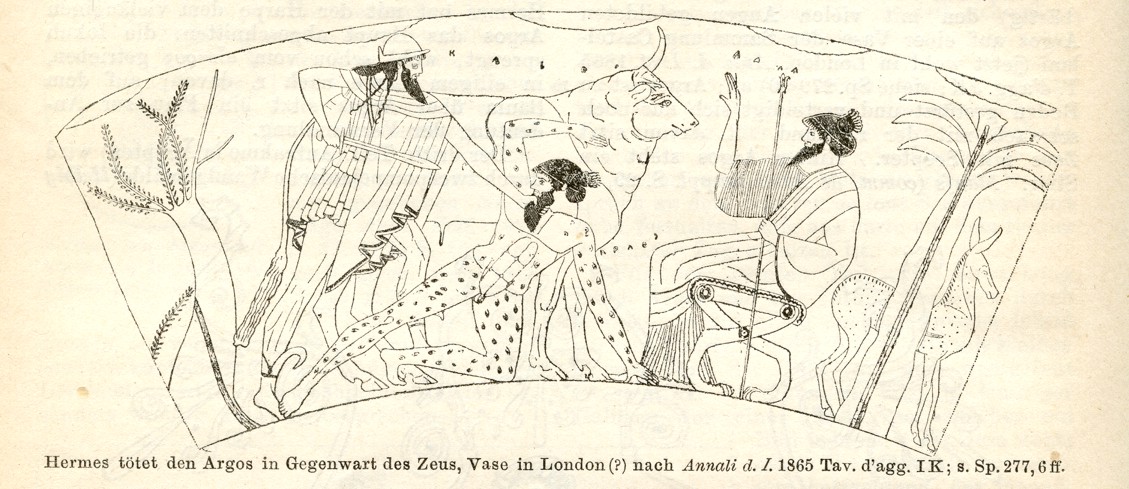

Argos, Io, and Hermes. Black-figure amphora, 540-530 B.C., from Italy. Staatliche Antikensammlungen (Munich) No. 585. (Image from Wikipedia.)

A rail tunnel under the Bosporus

A railway tunnel has been completed under the Bosporus, the strait dividing the eastern (Asian) and western (European) parts of the city of Istanbul. The 8.5 mile tunnel, first suggested by the Ottoman sultan Abdülmejid in 1860, dives 184 feet below the water, linking the two continents by rail for the first time. The Bosporus (Turkish Boğaziçi) is already crossed by two suspension bridges, the (First) Bosphorus Bridge (1973) and the Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge (1988), as well as numerous ferries. The Greek name Bosporus means "Cow's Crossing" and received its name from the myth of Io, the maiden loved by Zeus, who, turned into a cow and pursued by a stinging insect, raced across Europe and Asia in an attempt to find relief. How much easier would her crossing have been today!

But would they take a cow, if she had a ticket?

The tale is told in many versions. In most, she was the daughter of the river god Inachus. Zeus lusted after her, and covering her in a cloud to hide her from his wife Hera, ravished her. When Hera became suspicious, Zeus transformed her into a beautiful white heifer. Hera asked Zeus to give the cow to her, and he could not refuse. Hera put the hundred-eyed Argus Panoptes to guard her. Zeus sent Hermes to kill Argus (hence in Homer Hermes is called Argeiphontes "slayer of Argus"). Ovid, in his Metamorphoses (I.667-721) has Hermes first put the ever-watchful Argus to sleep by boring him with a long-winded story of the origin of the Pan-pipes. With his usual combination of pathos and humor, Ovid has Io, who can only moo, inform her distraught father that she is alive and well by tracing her story in the dust with her hoof! Hera sends a gadfly, an insect that afflicts cattle, to bite her incessantly, and she wanders the earth to escape it. Wandering over most of the known world, Io crossed the Bosposrus into Asia, finally arriving in Egypt, where, restored to human form by Zeus, she gave birth to Epaphus — "Touch" (of Zeus). Many generations later, she would become the ancestress of Heracles.

In an Ovidian mood, I picture a modern Io seated in a commuter train under the Bosporus, occasionally swatting with her tail at the fly buzzing around her head. I wonder what the other commuters would think. I wonder, too, about the fly's opinion. Did it resent having to go all over the world, when it only signed up to pester a cow in a field? Or would it enjoy the opportunity for foreign travel? In Egypt, its assignment over, did it settle down to a life of annoying the pharoah's herds?

Aeschylus' muddled geography

In Aeschylus' Promethsus Bound, Prometheus, chained to his rock by Zeus, is visited by Io on her travels. She, a fellow-sufferer at the hands of Zeus, tells her sad story, and Prometheus foretells her future wanderings and eventual release in Egypt. The Bosporus will be named for her crossing, and her descendant Heracles will finally deliver Prometheus from his bondage (in the lost Prometheus Unbound).

Our quotation of the month is from Prometheus' prophecy of Io's crossing of the strait that will be named (eponymos) for her feat. Aeschylus' narration is dramatic, but the geography is a bit muddled. He has her traveling through Scythia and the Caucasus before she crosses the Bosporus from Europe into Asia, which makes no sense. In a nice touch, he has her receive help from the Amazons, "who hate men" (styganor). They would sympathize with her treatment by Zeus!

Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 721-735

|

With Amazons' help, it will become the Bosporus

. . . [in the Caucasus] passing across star-neigboring |

Hermes kills Argos as Zeus looks on. Note that Argos has eyes all over his body. (Image from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Quotation for October, 2013: For Halloween, the Pumpkinification of Claudius, by Seneca |

Claudius as Jupiter. Statue in the Vatican Museum. This is how Claudius would prefer to be portrayed. (Image from Wikipedia.)

Claudius the underappreciated bumbler

The Emperor Claudius (ruled 41-54 A.D.) is sandwiched between the despotic Caligula and the much-loathed Nero. Over fifty when he became emperor, he was derided by his enemies as a clown, clumsy in both mind and body. After Caligula was murdered, Claudius, his uncle, was found hiding behind a curtain by the Praetorian guards and pressed by them to accept the imperial power. He had never participated in public life, devoting his life to antiquarian studies, including that of the Etruscan language, for which he wrote a (now lost) dictionary. He is the last person known to have been able to read Etruscan. His physical afflictions have been the subject of debate, possibly indicating a disability such as cerebral palsy.

Was he really that bad?

Claudius depended to a large degree on his freedmen, rather than the Senate, for advice and to fill important positions, activities that won him the dislike of the senatorial class. He was, however, popular with the public, and proved to be an able administrator. He increased the size of the Roman Empire, especially by the addition of Britain, and even himself made a trip to Britain to bring reinforcements, including elephants. He also increased the number of colonies that were granted Roman citizenship. His public works include two aqueducts, the Aqua Claudia and the Anio Novus. Claudius was married four times, his fourth wife being Agrippina, whose son (by a previous husband) was Nero. Agrippina induced Claudius to adopt Nero as his son, and Nero became the next emperor.

Claudius in the Underworld

Seneca the Younger was poet, dramatist, writer on Stoic philosophy and moral topics (as in the Epistulae Morales) and on science (the Queastiones Naturales). He wrote in short, epigrammatic sentences, eschewing the rolling cadences of Cicero. (Were he alive today, Seneca would probably use Twitter.) In and out of favor at the imperial court, Seneca was exiled by Claudius (probably influenced by third wife Messallina), but recalled after her execution (under the influence of fourth wife Agrippina) and made tutor to young Nero. When Claudius died (perhaps murdered), Nero became emperor. Later, out of favor again, Seneca was ordered by Nero to commit suicide, a fate shared by the satirist Petronius.

Claudius, like all emperors, was deified upon his death. (He was already worshipped, while living, in Britain, where he had his own temple.) Seneca, however, composed a satire describing a different fate. The Apocolocyntosis or "gourdification" of Claudius (a play on apotheosis or deification) is a "Menippean" satire, combining prose and poetry. In it, Claudius journeys to the Underworld, where his strange appearance and slurred speech are incomprehensible. Hercules, the world traveler, is called in to translate. What should be done with him? Should he be made a god? If so, what kind? He is berated for all the executions he has ordered, and is brought before Aeacus, one of the judges in the Underworld. There is a long discussion about his punishment. Should he substitute for one of the famous sinners, like Sisyphus, Ixion, or Tantalus? No, because he, too, might want to be pardoned. He is instead sentenced to play at dice, shaking them in a box with no bottom. Suddenly Caligula appears, claiming Claudius as his slave. Aeacus awards Claudius to Caligula, who gives him to Aeacus, who hands him to his Greek freedman Menander to be his law clerk.

A final joke: Despite the name of the satire, Claudius is never turned into gourd or pumpkin!

Below, in Latin and English, is the final scene of the Apocolocyntosis.

Seneca Apocolocyntosis 14-15

[14] . . . De genere poenae diu disputatum est, quid illum pati oporteret.

Erant qui dicerent, Sisyphum [satis] diu laturam fecisse, Tantalum

siti periturum nisi illi succurreretur, aliquando Ixionis miseri

rotam sufflaminandam. Non placuit ulli ex veteribus missionem dari,

ne vel Claudius unquam simile speraret. Placuit novam poenam

constitui debere, excogitandum illi laborem irritum et alicuius

cupiditatis speciem sine effectu. Tum Aeacus iubet illum alea ludere

pertuso fritillo. Et iam coeperat fugientes semper tesseras quaerere

et nihil proficere.

[15] Nam quotiens missurus erat resonante fritillo, Apparuit subito C. Caesar et petere illum in servitutem coepit; producit testes, qui illum viderant ab illo flagris, ferulis, colaphis vapulantem. Adiudicatur C. Caesari; Caesar illum Aeaco donat. Is Menandro liberto suo tradidit, ut a cognitionibus esset. |

A bottomless dice-box, a law clerk in Hades

. . . Over the type of punishment there was a long debate, as to

what was appropriate for him to suffer. There were those who said that

Sisyphus had carried his stone long enough, that Tantalus would

die of thirst unless he were given aid, that poor Ixion's wheel

should at some time be stopped. But it was decided not to give

release to any of the old ones, lest Claudius ever hope

for similar treatment. It was decided to arrange a new

punishment, that some labor should be thought up for him that was

in vain and had the appearance of some desire but without

effect. Then Aeacus ordered him to play at dice with a dice-box

with a hole in it. And Claudius began to look for the escaping

pieces, accomplishing nothing.

For whenever he was about to throw from his clattering dice-box Suddenly C. Caesar appeared and began to claim Claudius for a slave. He produced witnesses who had seen him being flogged by him with whips, rods, and fists. He was adjudged to C. Caesar. Caesar gave him to Aeacus, who handed him over to his freedman Menander to be his law-clerk. |

A coin of the Emperor Claudius. The inscription says: TI - CLAUDIUS - CAESAR - AUG[ustus} - P[ontifex] - M[aximus] - TR[ibunicia] - P[otestate] - IMP[erator]. (Image adapted from M. Cary, A History of Rome Down to the Reign of Constantine, second edition.)

Quotation for September, 2013: For the grape harvest of early fall, a selection from Vergil's Georgics |

Bacchus in procession, bearing a grape vine and accompanied by satyrs, one bearing a vat, another playing the flute, and a third carrying a wine-skin. Red-figured vase, depicted in a lithograph by L. Letronne, ca. 1840.

Following an ancient wine recipe

Archaeologists at the University of Catania, Sicily, have embarked on a project to make wine the old-fashioned way, following exactly the methods described by Vergil in his Georgics (36-29 B.C.) and by Columella in his De Re Rustica (ca. 60 A.D.), according to a piece in The Guardian online for August 22, 2013. Ancient techniques are being followed, from the planting of the vines, secured with twigs as the old authors describe and cultivated with wooden tools, to the natural fermentation, done without artificial agents in open terracotta pots lined with beeswax and buried in the ground up to the neck. (The modern project says nothing about foot-stomping of the grapes!) Pure varieties of ancient grapes can no longer be found, so a local variety, Nerello Mascalese, has been planted. Columella's guide to winemaking was, in fact, relied on until the 17th century, and Roman techniques were used in Sicily until a few decades ago. Mario Indelicato, who heads the program, says, "I discovered a two-pointed hoe at my family house on Mount Etna recently that was identical to one we found during a Roman excavation." A first vintage is expected within four years.

The article goes on to say that "Whereas Italians today drink moderately with meals, their ancestors were more given to drunken carousing. 'An edict was issued in the first century AD halting the planting of vineyards because people were not growing wheat any more,' said Indelicato."

Come, Bacchus, tread the grapes with me

Book I of Vergil's Georgics introduces agriculture, animal husbandry, and signs of impending weather. In Book II, he introduces viticulture and fruit trees, especially the olive. He goes on in Book III to describe the care of herds, especially cattle, and in Book IV to describe the care of bees. Our Quotation of the Month is an invocation to Bacchus from the beginning of Book II. Below, in Latin and English, are its opening lines. The "forest saplings" (silvestria virgulta in Line 2) are interpreted by T.E. Page as the young trees used as supports for the vines. Bacchus is called "Lenaean," Greek lênaios from lênos "wine press." Grape-stomping is featured here.

Georgic II 1-8

Hactenus arvorum cultus et sidera caeli |

Juicy grapes and bare feet

Thus far, it has been about cultivation of the fields and heaven's stars. |

Bacchus and Zeus, drawing from a vase painting. (Image from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Quotation for August, 2013: For the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington: Cicero on the meaning of freedom (in Paradoxa Stoicorum) |

Zeno of Citium, founder of the Stoics. Modern bust of Zeno in Athens. (Image from Wikipedia.)

The meaning of freedom

In August our nation commemorated the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington at which Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his "I Have a Dream" speech, one of the iconic moments in the struggle for civil rights. Featured speaker at the 2013 gathering at the Lincoln Memorial was President Barack Obama, whose election as the first African-American president is a fulfillment, at least in part, of Dr. King's dream of freedom and equality.

Our Quotation for August is from Cicero's Paradoxa Stoicorum, (Paradoxes of the Stoics), in which Cicero presents a Stoic view of the true meaning of freedom (libertas).

Only the wise man is truly free

Cicero probably wrote the Paradoxa Stoicorum around 46 B.C. In it, he lays out some of the apparently paradoxical beliefs of the Stoic school of philosophy. The Stoics believed that true happiness or peace of mind comes from a life of virtue, which they saw as living in accordance with the laws of nature. The Stoic school (so-called because they met the the Stoa Poikile or "painted colonnade" in Athens) was founded by Zeno of Citium (c.334-262 B.C.), but became popular in both Greece and Rome.

One of the paradoxes described by Cicero goes: "All wise men are free and all fools are slaves" (Omnes sapientes liberos esse et stultos omnes servos). That is, true freedom depends less on physical servitude or freedom than freedom of one's mind. The man who chases wealth or pleasure, for example, but whose attainment of those goods only leads him to want more and more, is enslaved by his obsessions, but that man is free whose life is an inner-directed striving after what is right. Cicero quotes "a wise poet" (whom he does not name) as saying that Fortune itself, whose gifts are the goal of many, is shaped by each person's character.

Below, in Latin and English, is an excerpt from the Paradoxa.

Paradoxa Stoicorum 34-534. Quid est enim libertas? Potestas vivendi ut velis. Quis igitur

vivit ut volt, nisi qui recta sequitur, qui gaudet officio, cui vivendi

via considerata atque provisa est, qui ne legibus quidem propter metum

paret, sed eas sequitur et colit quod id salutare esse maxime iudicat,

qui nihil dicit, nihil facit, nihil cogitat denique nisi lubenter ac

libere, cuius omnia consilia resque omnes quas gerit ab ipso

profisciscuntur eodemque referuntur, nec est ulla res quae apud eum

polleat quam ipsius voluntas atque iudicium, cui quidem etiam quae vim

habere maximam dicitur, Fortuna ipsa cedit, si, ut sapiens poeta dixit,

suis ea cuique fingitur moribus? Soli igitur hoc contingit sapienti,

ut nihil faciat invitus, nihil dolens, nihil coactus. |

Freedom of the mind, not obsession with chasing Fortune34. For what is freedom? The power to live as one wishes. But who

lives as he wishes, if not one who follows what is right, who rejoices

in doing his duty, whose way of life is considered and planned, who

does not obey the laws out of fear, but follows and cultivates

them because he considers them most beneficial, who says nothing,

does nothing, and, finally, thinks nothing if not willingly and freely,

whose every plan and action that he performs proceeds from him and

returns to him, for whom nothing has more importance than

his own will and judgment, and before whom even that which is said to have

the most importance, Fortune itself, yields, if, as the wise poet says,

each man's fortune is shaped by his own character?

Only to the wise man does it happen that he does nothing unwillingly,

nothing in sorrow, nothing because he is coerced. |

Bust of Cicero, 1st century A.D, in the Capitoline Museum. (Image from Wikipedia.)

The Emperor HadrianQuotation for July, 2013: A surveillance scandal: how Hadrian spied on the private lives of his soldiers |

Roman soldiers. (Illustration from Caesar's Commentaries: The Gallic War, Books I-IV, with Selections from Books V-VII and from the Civil War, with an Introduction, Notes, a Companion to Caesar and a Vocabulary, by Francis W. Kelsey, 1918.)

Spies in the news!

Patriotic whistleblower, who exposed intrusion by the U.S. government into the private lives of American citizens? Or evil traitor who gave away sensitive data, exposing America to the dangers of terrorist plots? The debate rages on about Edward Snowden, the National Security Agency contractor. Snowden disclosed the existence of government operations to electronically collect vast amounts of data on every conceivable form of communication between anyone and everyone, everywhere. While government spokespersons insist that only "metadata" (phone numbers, time of day, length of call) is collected, the potential is there for any lowly technician with a bunch of wires to read the actual contents of the phone call, e-mail, or social media posting.

Computers, the Internet, Facebook Twitter, and even the U.S.Mail, whose addresses and zip codes are now read (and potentially stored) electronically, have changed the world of spycraft dramatically since the early 20th century gave us Mata Hari and Reilly, Ace of Spies. But spies, both public and private, have always been with us. Odysseus asks the old nursemaid, Eurycleia, to report to him the names of the maidservants who had colluded with the evil Suitors (Odyssey 22.417-418). And under the Roman Empire, government spying took on the form of an organized and efficient network.

Hadrian's frumentarii

The Romans, with their far-flung empire and colonial activities, depended on spies and informers to maintain control over occupied lands as well as their own personnel. The emperors and their generals needed information on the size of enemy armies and local geography, and sometimes employed secret agents to carry out targeted assassinations. And of course, they were mindful of possible problems within their own ranks. The Emperor Hadrian (76-138 A.D.), best known for building Hadrian's Wall, which marked the limit of Roman Britain, is said to have created a secret police force employing officials known as frumentarii.

A frumentarius (from frumentum, "grain") was a functionary whose duty was to supply the army with grain and other provisions. This job brought the frumentarius into contact with the locals of an area, providing the opportunity to gather information and intelligence. Hadrian is said to have organized these officials into an efficient spy network. Our Quotation of the Month is from the Life of Hadrian in the Historia Augusta, a late Roman collection of biographies of Roman Emperors (and their heirs and usurpers), of uncertain authorship and uncertain reliability. It is a gold mine of dubious data, to be read with interest but approached with caution. Our quotation tells an anecdote about Hadrian's use of frumentarii to spy on his subordinates.

Historia Augusta, Hadrianus 11Et erat curiosus non solum domus suae sed etiam amicorum, ita ut per frumentarios occulta omnia exploraret, nec adverterent amici sciri ab imperatore suam vitam, priusquam ipse hoc imperator ostenderet. unde non iniucundum est rem inserere, ex qua constet eum de amicis multa didicisse. nam cum ad quendam scripsisset uxor sua, quod voluptatibus detentus et lavacris ad se redire nollet, atque hoc Hadrianus per frumentarios cognovisset, petente illo commeatum Hadrianus ei lavacra et voluptates exprobravit. cui ille: "num et tibi uxor mea, quod et mihi, scripsit?" |

How did you know what my wife said?Moreover, he was inquisitive not only about his own household but even about those of his friends, so that through the frumentarii he explored all their secrets, nor were his friends aware that their lives were known by the emperor until the emperor himself revealed it. Concerning this, it is not infelicitous to insert an incident from which it is evident that he found out many things about his friends. For the wife of a certain man had written to her husband that, preoccupied with pleasures and baths, he was unwilling to return to her, and Hadrian found out about this through the frumentarii. When the man requested a leave of absence, Hadrian reproached him with his baths and pleasures. Whereupon the man said, "What, did my wife write to you, too, the same thing she wrote to me?" |

Roman soldiers. (Illustration from Caesar's Commentaries: ed. Francis W. Kelsey, 1918.)

Quotation for June, 2013: Woman Power! Cynisca from Sparta wins the Olympic four-horse chariot race (396 and 392 B.C.) |

An archaic votive relief from Chrysapha in Laconia, near Sparta. A hero offers a libation, accompanied by a horse and dog. Cynisca, from Sparta, the first woman to win in the Olympic Games, racing her four-horse chariot, bore a name (or nickname?) that means "little hound." Perhaps in strength and vitality she resembled the eager pup pawing at the hero's leg. (Illustration from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Women and horses

Once again, there was no triple crown winner at the horse races. The Kentucky Derby, Preakness, and Belmont were won, respectively, by Orb, Oxbow, and Palace Malice. But history was made in other ways. A woman jockey, Rosie Napravnik, rode in all three races, the first woman to do so, finishing fifth and third in the Derby and Preakness, and sixth in the Belmont, aboard a filly, Unlimited Budget. More female power! History was also made by the black jockey Kevin Krigger, who had hoped to be the first African-American to win the Derby since 1902, in a sport once dominated by black jockeys.

The "little hound" is the first woman Olympic winner

This month, we think it appropriate to celebrate another woman who made history in the sport of horse racing. Cynisca, the Spartan princess whose four-horse team won at Olympia in 396 B.C. and again in 392, was the first woman to win in any sport at the hallowed Olympic Games. Spartan women, unlike their Athenian and other counterparts, excelled at sports, exercising naked (or half-naked) like the men, attended symposia and drank wine with the men, and owned their own property. They were expected to be strong so that they could raise strong sons, but were also expected to be strong on their own account. Sparta was known for breeding horses, and women as well as men had had an affinity for horses.

Cynisca was the daughter of one Spartan king, Archidamus II, and the sister of two later kings, Agis II and Agesilaus. Very likely a tomboy, she bore a name (or nickname) that means "little hound," a name that calls up not the current negative connotation of the female dog but the eager, loyal hunting companion, like Odysseus' faithful hound Argos. Her grandfather, Zeuxidemus, was also nicknamed "Kyniskos." Cynisca was undoubtedly the owner, rather than the driver, of the horses and chariot, and it is unlikely that she actually drove the chariot herself. Following her victory, other Spartan women also competed and won in chariot racing.

Cynisca's victory monument

After her victory, Cynisca erected a monument at Olympia, with statues of herself and of her chariot and horses, with an inscription bragging of her victory. This monument was described by Pausanias (iii.8.2) and the inscription is included in the Greek Anthology (Anthologia Palatina xiii.16). The statues themselves are gone, but In 1879 the remains of a statue base bearing the inscription was found at Olympia. The text was mutilated, but can be restored from the Greek Anthology. Another inscription on the statue base announces the name of the sculptor, reading "Apelleas, son of Callicles, made [it]."

The restored epigram celebrating Cynisca appears below.

Inscription from Cynisca's monument at Olympia

|

The winner!

Kings of Sparta are my fathers and brothers. |

The old nurse Eurykleia recognizes the disguised Odysseus on his return to Ithaka by the scar on his leg, as she washes his feet. His faithful dog is pictured beside him. As a matter of fact, the Odyssey movingly describes how old Argos, recognizing Odysseus for the last time, wags his tail and dies. Perhaps this is a different dog? (Illustration from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Quotation for May, 2013: For Memorial Day, the funeral of Achilles, as described in Odyssey Book 24 |

Alexander the Great at the Tomb of Achilles, a fanciful painting by Giovanni Paolo Panini (ca.1718), in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. The story of Alexander visiting Achilles' tomb is found in Plutarch, Alexander 15. In the version of the story followed by Panini, Alexander asked that the tomb be opened for him to pay his respects. The actual tomb of Achilles, if it exists at all, may be the mound at Kesik Tepe, Turkey. (Image from Wikipedia.)

A hero's funeral

In the Odyssey, the most famous Journey to the Land of the Dead is in Book 11. Odysseus performs the rite of the nekyia, calling up the dead around the blood-filled trench, and a sad and macabre parade of lost souls comes to drink from it. Odysseus meets with the great Theban seer Teiresias, "to whom alone Persephone granted reason even after death," who foretells his future. He meets the shade of his mother, who achingly melts from his arms as he tries to embrace her, and he sees the ghosts of countless heroes and villains, the famous and the infamous.

Less well-known is a Journey to the Underworld in Book 24. Here the souls of the evil Suitors, slain by Odysseus on his return to Ithaca, are led by Hermes, "gibbering like bats," into the Land of the Dead. There, they find the ghosts of Achilles and Agamamnon deep in conversation. Agamemnon describes to Achilles the glorious funeral provided for him by his mother, the sea nymph Thetis. He describes the great frightening cries of grief of Thetis and her fellow nymphs, the sacrifices of sheep and cattle, the great funeral pyre, the golden urn in which Achilles' ashes were mingled with those of his friend Patroclus, the funeral games played in his honor, and finally the tomb and funeral mound. Agamemnon contrasts Achilles' glorious death with his own sorry death at the hands of his wife Clyatemnestra and her lover Aegisthus.

In our Quotation of the Month, Agamemnon describes Achilles' funeral and the games decreed by Thetis.

Homer Odyssey 24.63-94

|

You were given a glorious funeral, Achilles

For seventeen days, yea, both nights and days, |

The fight over Achilles' body. (Illustration from Roscher's Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.) Ajax alone holds off the Trojans. We can see that Achilles has been shot in the heel with several arrows.

Quotation for April, 2013: For the opening of a Presidential Library, Horace declares his poetry more lasting than the pyramids |

The pyramids at Giza, Egypt, depicted on an old postcard. Horace's poems, which he declared were more durable than the pyramids, are still known today, but so are the pyramids!

Presidential pyramids

This April sees the dedication of former President George W. Bush's Presidential Library at Southern Methodist University (SMU) in Dallas, Texas. An invitation-only dedication ceremony will occur on April 25, 2013, followed by a public opening on May 1. According to the official Web site, "The Bush Center, which houses the George W. Bush Presidential Museum and Library and the George W. Bush Institute, combines the nation’s 13th Presidential Library and Museum with a leading-edge policy organization that continues the public service of President and Mrs. Bush." Recent presidents have established official libraries to collect and make accessible their presidential papers and memorabilia when their time in office is over. These libraries also serve the purpose of building a monument to themselves.

Rulers and leaders (or their followers) have always erected monuments to their prowess, from the pyramids of Egyptian pharoahs and Aztec kings to bronze statues of emperors to today's presidents. Sometimes the ruler becomes the monument, like the preserved bodies of Lenin and Eva Peron. There is talk of similarly preserving the remains of Venezuela's Hugo Chavez. This behavior is a manifestation of the natural desire for something of us to remain when we are gone. For some, it is the soul that goes to heaven after death, for others it is the presence of children and grandchildren. Non omnis moriar, "I shall not entirely die," says Horace. But where the result assumes an aura of grandiosity, Horace offers a corrective.

The poem is mightier than the pyramid

In 23 B.C., Horace published Books I-III of his Odes, to which he appended Ode 30 as an epilogue. In it he brags that his poems are more enduring than bronzes and pyramids, not subject to rain and wind. Through them he will live forever. His time frame is strangely local: "As long as the pontifex (chief priest) ascends the Capitol with the (Vestal) virgin, I shall be known," he says, and his geographical frame is small, too, extending to "the torrent of the Aufidus and the land ruled by Daunus," spots near his home in Apulia. The Vestal Virgins are gone, and so is the Pontifex. Or is he? The Pope is commonly called the Pontifex Maximus, though he ascends the steps of the Vatican unaccompanied by Vestal Virgins. Horace's poetry is read by all who study Latin, but the Pyramids are still there, too.

Below, in Latin and English, is Horace's poetic boast. The regali...situ pyramidum, which I translate as the "royal pile of the pyramids," can either be the "site" or "situation" of the pyramids, or their "decay," that is of something left lying around too long! Aquilo is the destructive north wind, and Libitina was the goddess of burials, in whose temple equipment for funerals was kept and death records registered. "Aeolian song" refers to Horace's adaptation of the metres of Sappho and Alcaeus to the Latin language. Melpomene, the Muse of tragedy, stands here for any of the Muses.

|

Horace Carmina III.30

Exegi monumentum aere perennius |

My fame will live foreverI have completed a monument more lasting than bronze,

|

A stern looking chief Vestal Virgin, from Rodolfo Lanciani, Ancient Rome, in the Light of Recent Discoveries, 1898.

Quotation for March, 2013: Springtime is growing season, as described in Hesiod's Works and Days |

Plowing with oxen, detail from the Papyrus of Ani, British Museum. Ani's life in a blessed hereafter is represented in this papyrus, as he plows, reaps, and worships the gods. (Image from The Book of the Dead, English translation by Sir E.A. Wallis Budge, second edition, 1949.)

Plant early, or hope for soaking rain

Spring has come to the northern hemisphere, and with it planting and growing season. Even urban dwellers have gotten into the back-to-the-earth movement. Gardens sprout on rooftops, and composting and hydroponic kits are available for those who want to practice windowsill gardening. Some Brooklyn residents are even raising chickens for their eggs. We ourselves will soon be starting our tomatoes in the back yard.

This month, we offer Hesiod's description of how and when to plow, sow, and reap a good crop of grain, in a passage taken from his Works and Days (Erga kai Hemerai).

In the Mediterranean climate, the rainy season is in winter, so plowing must be done at the beginning of winter, "when the cranes call." There appear, however, to be three seasons for plowing: fall, spring, and summer. We are reminded of the goddess Demeter, who "lay in love with Iasion in a thrice-plowed fallow field," bringing fertility to the crops (Theogony 970-971). If you plow too late, Hesiod tells us, you can hope that Zeus will send a heavy rain. Then even the late farmer can match the early planter in output. Hesiod pictures the farmer working side-by-side with his slaves (dmos, literally "one taken in war," a frequent cause of servitude. Later philosophers began to decry the practice).

Below, in Greek and English, is Hesiod's advice on the necessity for timely plowing and planting.

Hesiod Works and Days 448-492

|

Advice on plowing and plantingConsider, when you hear the voice of the crane, |

The old ways have persisted in modern times. The photo above of a couple with their new plow was taken on one of the trips in Mexico that I took with my father as a teenager in the 1950's.

Quotation for February, 2013: for Valentine's Day and intimations of spring, Eros plays tag with the poet Alcman. |

Sparta is known as sternly militaristic, but she had another side. Free-spirited Helen of Troy was Queen of Sparta, wife of King Menelaus, and this month we bring you a poem on love from the Spartan poet Alcman. The illustration depicts Helen eloping with Paris in a Hellenistic terra cotta. (Image adapted from An Outline History of Art, 1938.)

From Sparta with love

February is the month of Valentine's Day, and at least in some places, the early crocus is blooming and the first green shoots of daffodils have started to appear. In other snow-blown states, spring is still a few dreams away. This month, we offer some words on love from the poet Alcman, who composed songs for maiden choruses in 7th century B.C. Sparta.

Sparta as the antithesis of Athens

Sparta is, to most modern readers, the anti-Athens. Where Athens was democratic, Sparta was oligarchic. She had a dual kingship, with both kings supposedly descended from Herakles. Where Athens was a sea power, Sparta excelled in land war, having perfected the infantry line of hoplites ("armored men"), with their overlapping shields. Sitting on low hills between the Eurotas River and Mount Taygetus, Sparta had a small acropolis, crowned with a temple to Athena of the Bronze House, but no fortifications. Unlike Athens, famous for overwhelming monuments, Sparta was described as looking less like a city than a collection of villages. In contrast to garrulous Athenians, Spartans were sparing of speech and short on philosophizing — in other words, "laconic," (after Lakonia, their region). Boys were trained in a rigorous state-sponsored system of education to be warriors, taking their meals in common messes.

Girls, too, received an education, and, like the boys, performed naked gymnastics. Women drank wine at symposia like men, and some even owned horses that they entered in the Olympic Games. As the men engaged in warfare, conquering much of the Peloponnese, they left farming and manual labor to the helots, who, unlike slaves, were not owned, but were serfs who were tied to a particular plot of land, and to the perioikoi, or "dwellers-around," free inhabitants of lesser villages of the region. Sparta's laws were given them, supposedly, by the lawgiver Lycurgus, whose reality is even now debated. Descendants of the Dorian migration that swept into southern Greece from Macedonia after the disintegration of the Mycenaean society celebrated by Homer, Spartans cultivated a persona of stern military virtue. Under Leonidas, they were the heroes of Thermopylae in the Persian Wars, but in the following Peloponnesian War they were the enemies of Athens.

Sparta's softer side

But Sparta had a more cheerful side. Especially in the archaic period before 600 B.C., Sparta excelled in decorated vases and ornate bronze work that were exported as far as Gaul. Not only were young women encouraged to be strong, they were taught to be graceful in song and dance. Like the boys, girls were taught to be competitive, organized into teams of dancers, for whom poets composed choral songs. Even in Homer, Sparta is described as kalligunaika, having beautiful women, and Pindar said of the city (as quoted by Plutarch in his Life of Lycurgus 21.4):

There the councils of old men

and young men's spears excel

and dances and the Muse and splendor.

The most beautiful and independent Spartan woman of all was, of course, Helen, who started the Trojan War. A queen from the Mycenaean era, she and King Menelaus continued to be worshipped in the Menelaion, across the river from Sparta (a worship perhaps indicating an origin as a local goddess).

Alcman's poetry for maiden dances

Sparta's most famous 7th-century poets were Tyrtaeus and Alcman. Tyrtaeus composed martial songs to exhort the fighting men. Alcman excelled at parthenaia or "maiden songs" for girls' choral dance, composed in the Doric dialect. Both poets' work exists only in fragments, on scraps of papyrus or in short quotations used by later authors to illustrate points of grammar or meter. Alcman was reputed to have invented Doric love poetry, but his praises of young women were more likely simply part of the festive performance.

For February, we present a delightful little fragment of Alcman, soberly quoted by Hephaestion's Handbook of Metre as an example of the cretic meter (-u- or long-short-long). We do not know the original context, but in its current state it has a haiku-like quality, describing the stirrings of love as not a full-on blow from Aphrodite, but simply a tap from a child-like Eros "playing a game of tag."

Below, in Greek and English, is our fragment of Alcman. The Greek is the heavily emended text of the Loeb edition by J.M. Edmonds.

Alcman IV.131

|

Eros plays tag with meIt's not Aphrodite! it is mad Eros who like a child plays,going softly on tiptoe, a game of "don't touch me with your little reed." |

Aphrodite and Eros, detail from east frieze of the Parthenon. (Illustration from Seyffert's A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

Quotation for January, 2013: Does the presence of weapons itself inspire violence? (Odyssey 19.1-13 (and 16.284-294) |

Herakles, in a pose that might have been taken by Odysseus, draws his mighty bow. The hero wears a helmet made from the head of the slain Nemean Lion, whose hide was impenetrable to weapons. Sculpture from the east pediment of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina, ca. 500 B.C. (Image from An Outline History of Art, 1938.)

"Iron draws a man on"

Gun violence has risen to the top of the national consciousness, with a series of mass shootings carried out by deranged individuals. Especially horrific was the killing of schoolchildren and their teachers in Connecticut. These rampages have gotten the public attention where individual killings, seemingly random, have not. But there is no consensus on what should be done. Outlaw assault weapons and high-capacity ammunition clips? Increase treatment for mental illness? Ban violent video games? Post armed guards at every school? The Second Amendment guarantees "the right of the people to keep and bear arms," but what, exactly, does that mean? On the one hand are those who would ban all firearms, real or depicted (as in the case of a child suspended for drawing a picture of a gun in art class!). On the other are those who hunt and fish to supplement their dinner table, sportsmen, persons engaged in dangerous jobs where a gun is owned for personal protection, and survivalists (or "preppers") who practice an extreme form of emergency preparedness, stockpiling food, water, other supplies, and weapons in anticipation of a natural or man-made apocalypse. Like the sword in other cultures (or the bow in Homer), the gun in America is a personal and emotional object.

Many deaths by gunfire occur because a gun was available when less lethal means might otherwise be used. Deaths are caused by jealous lovers, gang warfare, road rage, or accidental stray bullets intended for someone else. How many bar fights end in gunfire that might otherwise be settled with fists? As I listened to the arguments, the line that ran through my mind was the line from Homer:

. . . autos gar ephelketai andra sideros.

. . . for the iron of itself draws a man on.

Odysseus and Telemachus remove the arms from the hall

In Odyssey Book 19, Odysseus, having returned to Ithaca, tells his son Telemachus to remove his old armor and weapons from the megaron or great hall. Telemachus is to tell anyone who asks two false reasons for their removal: First, that hanging unused for twenty years, they have been damaged by smoke from the central hearth. Second, that should a fight break out among the banqueters when they have drunk too much wine, the availability of weapons might lead to bloody consequences — "The iron of itself draws a man on." (With slight variations, the same lines occur in Book16.284-294, when Odysseus and Telemachus first hatch their plot.) The real reason, of course, is that Odysseus plans to slaughter all the Suitors who are wooing his wife Penelope and using up all his food and drink. Penelope promises to marry the man who can string the bow of Odysseus and shoot an arrow through a tunnel of axe heads, but of course only Odysseus, in his disguise as a beggar, can string and shoot the mighty bow, with which he proceeds to dispatch the Suitors. The Suitors have their own swords, but Odysseus, Telemachus, and their allies the faithful cowherd and swineherd, have access to the stored weapons removed earlier from the hall. An interesting aspect of the story is its evidence that a lightly armed or unarmed crowd is helpless against a determined invader. But since the Suitors are presented as the "bad guys," we cheer for Odysseus, who is the "good guy."

The magnetic power of iron

The word sideros "iron" to mean "weapon" has long puzzled critics as a anachronism. Homer composed his poems in the Iron Age, but the story takes place in the Late Bronze Age, when most weapons were still of bronze, although knives and axes were made of iron. Some have suggested a reference to magnetic and magical powers of iron. Perhaps there is a play on meanings: "Iron (weapons) draw men to them (like a magnet)."

Below, in Greek and English, is the passage from Book 19 of the Odyssey.

Odyssey 19.1-13

|

An excuse for removing weapons from the hallAnd so godlike Odysseus was left in the hall,plotting slaughter against the suitors, together with Athena. Quickly he addressed winged words to Telemachus: "Telemachus, we must store the warlike weapons inside, all of them. But you must beguile the suitors with gentle words, when they miss them and question you. 'I stored them away from the smoke, since they no longer resembled such as those which Odysseus once left behind when he went to Troy, but they are filthy, so much have fumes from the fire reached them. In addition, a god has put a greater concern in my heart, lest drunk with wine and starting a fight among yourselves, you wound each other and bring shame on your feast and on your wooing. For the iron of itself draws a man on.'" . . . |

Odysseus, homeward bound, is tied to the mast of his ship, as he listens to the Sirens sing their deadly invitation. He has put wax in the ears of his companions, so that they are not distracted from their rowing. The Sirens are depicted as half-bird, half-woman. (Image from M. Rostovtzeff, A History of the Ancient World, Vol. I, 1926.)

<---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2014 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: