These are quotations for the year 2014. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations.

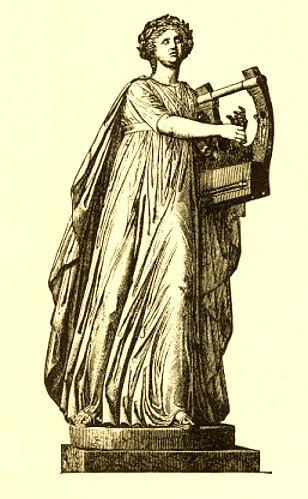

Illustration: Apollo, patron god of music, plays the lyre, the instrument with which the bard accompanied himself as he sang of mythical stories or the news of the day.

Archived quotations of the month |

|

Beginning with September, 2004, my home page will feature a different quotation from Classical or other literature each month, appropriate to the season or to current events. Starting in October, 2004, these pages will contain "Quotations of the Month" from previous months. Translations are my own, except where otherwise noted. Below is the index to the quotations for 2014, followed by the quotations themselves. |

Index to quotations for 2014 |

Below are quotations for the year 2014. For other years, go back to the first quotation page for the Index to Quotations or click on one of the years below:

Quotations of the Month for the year 2014

Click on a link to read each quotation

2014

- December, 2014: For the Holiday Season: Theognis on the perils of hard partying.

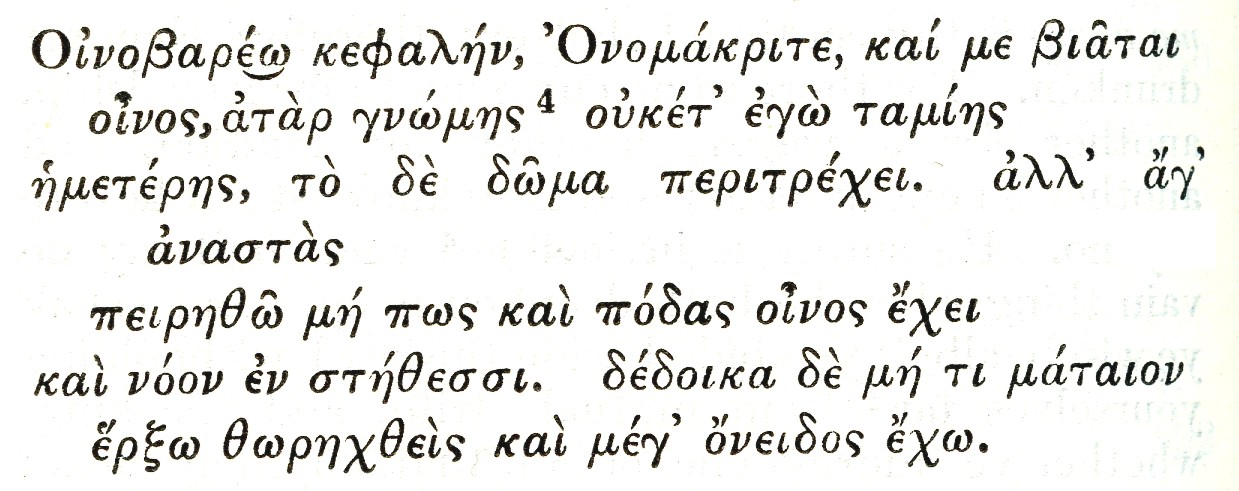

- November, 2014: Honoring the European landing on a comet: Vergil celebrates Julius Caesar's Comet.

- October, 2014: For Halloween: Cynthia's wild ghost visits Propertius.

- September, 2014: In honor of Apple's introduction of its new iPhone: How Propertius lost his iPhone, er, wax tablets.

- August, 2014: Alexander the Great and a camel; Irbil: crossroads of ancient and modern worlds.

- July, 2014: Odysseus in Arkansas: Meeting new acquaintances far from the sea (Odyssey Book 11).

- June, 2014: For the 70th anniversary of D-Day, the departure of the Athenian fleet for Syracuse, described by Thucydides.

- May, 2014: For the anniversary of Charles Lindbergh's flight, Ovid's tale of Daedalus and Icarus.

- April, 2014: Ovid, in his Fasti, discusses the origin of the name "April."

- March, 2014: Vladimir Putin Among the Hyperboreans: Callimachus' Hymn to Delos and gifts for Apollo from beyond the North Wind.

- February, 2014: In honor of the Winter Olympics, we celebrate, with Pindar's First Pythian Ode, the festivities around the games (they make Zeus's eagle fall asleep).

- January, 2014: For a cold winter, stay inside and play games (Jacob Bigelow, 1808}.

Quotation for December, 2014

For the Holiday Season:Theognis on the perils of hard partying |

A picnic with flute music. One of many whimsical illustrations hand painted in my copy of Poets of the Greek Anthology, translated by F.A. Wright, London, 1924, by a former owner, whose talents, alas, remain anonymous.

Time to celebrate

Happy New Year! The year's end is a time of celebration — Christmas, Hanukkah, New Year's, the Winter Solstice. The sun pauses, and turns back in the sky, the beginning of winter in the Northern Hemisphere, of summer in the Southern half. There are family get-togethers, parties at social clubs, office parties for workers, as well as religious rituals. There are fireworks and much merry drinking. As we race down the Appian Way in our chariots, we are urged to have a designated charioteer. This month we offer some rueful couplets from an ancient Greek poet, Theognis of Megara.

Theognis on how to live your life

Theognis lived, it is thought, in the sixth century B.C. Little is known of his life. In fact we are not even sure which "Megara" he was from. He is most commonly thought to have been born in Attic Megara, a city which was (and is) located in the south west corner of Attica, on the Isthmus of Corinth, on the road from Athens to the Peloponnese. A rival theory placed him in the colony of Megara Hyblaea, in Sicily. His surviving poetry is a large collection of aphoristic verses, much of it moralizing, written in the elegiac meter, with each line of hexameter in the epic style followed by a shorter line. The tone is reminiscent of Hesiod's Works and Days, but Theognis' Elegies lack the structural coherence of Hesiod's work. Where Hesiod's Old Farmer's Almanac tied a series of entertaining myths (including Prometheus and Pandora) to the seasons of the year, Theognis' couplets jump from topic to topic in no particular order. He discusses subjects such as friendship, wealth, poverty, and marriage, then revisits favorite topics multiple times. Some have questioned whether the collection is by one author.

The room is spinning around!

A number of Theognis' verses have to do with wine, a good thing in moderation, bad in excess, a concept boiled down in the following couplet (ll. 211-212):

Oinon toi pinein poulun kakon; ên de tis auton

pinê epistamenos, ou kakos all' agathon..

To drink a lot of wine is bad. But if someone

drinks it with knowledge, it is not bad but good.

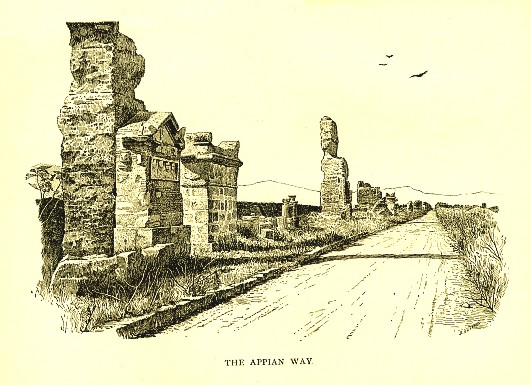

But Theognis was apparently familiar with the effects of overindulging. In a longer set of verses (503-508), he describes the sensations: the room spins around (peritrekhei "runs around"); he will stand up to see if the wine affects his ability to walk (podas oinos ekhei "the wine possesses my feet") — any bets on that? Above all, he is afraid he will do something stupid (mataion) and be embarassed (meg' oneidos ekho "I [will] have great shame"). The verses are addressed to Onomacritus, otherwise unknown.

Below, in Greek and English, is Theognis' description of his experience with too much booze.

Theognis 503-508

|

|

I've had too much

I am heavy with wine in my head, Onomacritus, and the wine |

Dionysos and Eros — wine and love always go together! (Image from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Quotation for November, 2014

Honoring the European landing on a comet:Vergil celebrates Julius Caesar's Comet |

The Hale-Bopp Comet, next to the (faintly seen) Big Dipper, appears above the trees in my yard on an evening in April, 1997. The Heaven's Gate cult believed that a spaceship accompanying the comet would come and take them up to a better life.

The Europeans land on a comet

On November 12, 2014, the European Space Agency's space probe, Philae, landed on the surface of the comet known as 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Philae was transported to the rendevous by the Rosetta spacecraft, which began its incredible ten-year voyage to the comet in 2004. Rosetta was named for the Rosetta Stone, which, with its inscription in Egyptian hieroglyphs, Demotic Egyptian script, and Ancient Greek, was the key to deciphering the ancient hieroglyphs. Philae, an island situated in the Nile (the Egyptian name Pilak meant "boundary"), was sacred as one of the burying places of Osiris, and contained a large temple complex (whose buildings were moved to another island in the 1960's because of flooding from damming of the Nile). The Philae Obelisk, containing a petition from priests of Osiris, written in Egyptian hieroglyphics, was helpful to Champollion in his deciphering the Rosetta Stone. The Rosetta space mission and its Philae lander, are helping scientists decipher the nature of the little comet's core.

What are comets?

Comets, with their spectacular glowing manes of dust and gases (the Greek name aster kometes means "long-haired star") are now known (at least those that have been studied) to have a hard nucleus, mostly of ice mixed with or covered with dust. Like planets, they orbit the sun, in long parabolic orbits. Some, like Halley's comet, are regular guests. Others are infrequent visitors, or may never be seen again, either disintegrated or permanently escaping the solar system. Anaxagoras and the Pythagoreans believed that comets were planets. Aristotle, however, believed that they are atmospheric phenomena emanating from the Earth's own atmosphere, and this theory held for many centuries.

Comet superstitions, ancient and modern

Superstitions regarding comets have always been around, often associating them with misfortune and disaster. When Julius Caesar was assassinated In 44 B.C., a comet, bright enough to be seen in daylight, appeared during the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris, a festival held by his heir and successor Octavian, soon to be the Emperor Augustus, to commemorate the assassination. Suetonius tells us it was visible for seven days, and was thought to be Caesar's soul, a sign of Caesar's deification. Caesar's comet (whatever it was, if indeed it existed) was never seen again. Superstitions about comets persist to this day. In 1997, thirty-nine Heaven's Gate cult members committed mass suicide, thinking they would be taken up into a spaceship accompanying the Hale-Bopp Comet.

Vergil celebrates Caesar's Comet

Caesar's Comet, real or not, became a powerful tool in the propaganda of the new emperor. Both Vergil and Ovid tell of the comet, each in his own way. Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, describes how the soul of Caesar was transformed into a stellam comantem, and in his usual way, emphasizes the human interest aspect of the story, as Caesar's ancestress Venus (as mother of Aeneas) tries in vain to save his life. There are many portents, including phantom sounds of battle in the sky, clouds dripping blood, weeping statues, and ill-omened entrails (Metam. XV.745-842). Vergil tells a similar story, but puts it at the end of his First Georgic (vv. 461-488), where his description of floods, earthquakes, human-voiced cattle, grieving statues, and comets (plural!) forms the climax of his advice to the farmer regarding celestial signs of good and bad weather. Vergil ends the episode with a heartfelt prayer to the gods to aid the young emperor in bringing renewed peace and prosperity.

Below, in Latin and English, is an excerpt from Vergil's First Georgic. "Eridanus" is another name for the Po River.

Vergil,Georgic I 461-488 . . .Denique, quid vesper serus vehat, unde serenas ventus agat nubes, quid cogitet umidus Auster, sol tibi signa dabit. solem quis dicere falsum audeat? ille etiam caecos instare tumultus saepe monet fraudemque et operta tumescere bella. ille etiam exstincto miseratus Caesare Romam, cum caput obscura nitidum ferrugine texit impiaque aeternam timuerunt saecula noctem. tempore quamquam illo tellus quoque et aequora ponti, obscenaeque canes importunaeque volucres signa dabant. quotiens Cyclopum effervere in agros vidimus undantem ruptis fornacibus Aetnam, flammarumque globos liquefactaque volvere saxa! armorum sonitum toto Germania caelo audiit, insolitis tremuerunt motibus Alpes. vox quoque per lucos vulgo exaudita silentis ingens, et simulacra modis pallentia miris visa sub obscurum noctis, pecudesque locutae, infandum! sistunt amnes terraeque dehiscunt, et maestum inlacrimat templis ebur aeraque sudant. proluit insano contorquens vertice silvas fluviorum rex Eridanus camposque per omnis cum stabulis armenta tulit. nec tempore eodem tristibus aut extis fibrae apparere minaces aut puteis manare cruor cessavit, et altae per noctem resonare lupis ululantibus urbes. non alias caelo ceciderunt plura sereno fulgura nec diri totiens arsere cometae. . . . |

Give heed to celestial signs

. . . |

Coin of Augustus Caesar, with Julius Caesar's Comet on the reverse.

Quotation for October, 2014

For Halloween:Cynthia's wild ghost visits Propertius |

The Appian Way. Cynthia, buried near a busy road, wished her epitaph kept short, to be easily read by the hurried passerby. (Illustration from Rodolfo Lanciani, Ancient Rome in the Light of Recent Discoveries, 1898.)

Cynthia the free spirit

"Cynthia" was Propertius' obsession, his muse, the center of his emotional, sexual, and poetic life. Cynthia prima fuit, Cynthia finis erit ("Cynthia was the first, Cynthia will be the end") he wrote (Propertius I.12.20). Her real name was Hostia, and she may have been a descendant of the Roman poet Hostius. She was, it seems, not a common prostitute, but more likely an experienced "party girl" who attracted well-heeled lovers. Propertius, a young poet who joined the circle of the wealthy Maecenas (also the patron of Horace and Vergil), was mesmerized. Hostia was beautiful, intelligent (he calls her docta puella, "learned girl"), demanding, self-absorbed, fickle, and self-dramatizing. She was insanely jealous of other women in Propertius' life, but expected complete freedom, sexual and otherwise, for herself. The relationship did not go smoothly. They broke up, they got back together. She could make him miserable. But she inspired some of his finest poetry. He called her "Cynthia" after Mount Cynthus on Delos, birthplace of Apollo, god of song and poetry. His first book of elegies is called Cynthia monobiblos "One book about Cynthia."

And then Cynthia died. By now Propertius was writing his fourth book of poems. The affair was over, and Propertius had moved on to other poetic themes and, presumably, other loves. But his bipolar emotions remained. He continued to write poetry, but the fire was gone.

Cynthia's angry ghost

Book Four contains two poems about Cynthia, No. 7, in which Cynthia's ghost, fresh from the funeral pyre, visits Propertius in a dream, and No. 8, a vivid picture of Cynthia very much alive. They go together — Cynthia the wild woman in death as in life.

In No. 7, Cynthia appears to Propertius as he tosses and turns in his lonely bed. She is gruesomely burned, with her charred clothing sticking to her body, and her bones rattle. She berates him for daring to sleep, and for not calling her name as she died (it might have bought her an extra day of life). She accuses him of not giving her a lavish enough funeral. She recalls their adventures, as when she climbs down a rope at night to meet him (apparently to escape the notice of her current boyfriend). She accuses his servants Lygdamus and Nomas of poisoning her, and of mistreating her faithful attendants for praising her. She launches into a mythological digression (she is a docta puella, after all) about the fate in the Afterlife of famous villainesses like Clytaemnestra (who killed her husband Agamemnon) and famous heroines like Hypermestra (who refused to kill hers). She concludes by ordering Propertius to pension off her faithful servants, and to erect a memorial column by the river Anio at Tibur with an epitaph short enough to read on the run. With characteristic narcissism, it is to announce that "Here lies golden Cynthia, who brings honor to the Anio." Ghosts, she tells him, and even the dog Cerberus, wander at night, to be ferried back across Lethe at dawn. Gruesomely and theatrically, she tells Propertius it is all right if he takes other lovers, because "soon you will be all mine, and our bones will grind together" eternally mingled. And then she vanishes as he tries to embrace her.

Live Cynthia recalled

Live Cynthia remembered in No. 8 is counterpoint to dead Cynthia in No. 7. Cynthia leaves Propertius to go to a festival of Juno (more likely Venus, as he says sarcastically). He pictures her flying down the Appian Way, driving her own team of horses, with her latest boy toy in tow. Propertius comforts himself by inviting over two girls who could be counted on for fun, while the servant Lygdamus serves them wine. The threesome are having a good time when Cynthia suddenly throws open the doors, "her hair undone, but lovely in her fury." Cynthia beats up on the two girls, who flee. She demands that Lygdamus be put in chains (she accused him of poisoning her in the previous poem). She purifies the house with incense and throws out everything the interlopers have touched. Then she and Propertius make love.

In life, Cynthia was dramatic, and in death she was dramatic, too. She was his wild woman, and he loved her.

Below, in Latin and English, are the opening and concluding verses of Propertius 4.7.

Propertius Elegies IV.7.1-24, 71-96Sunt aliquid Manes: letum non omnia finit,luridaque evictos effugit umbra rogos. Cynthia namque meo visa est incumbere fulcro, murmur ad extremae nuper humata viae, cum mihi somnus ab exsequiis penderet amoris, et quererer lecti frigida regna mei. eosdem habuit secum quibus est elata capillos, eosdem oculos: lateri vestis adusta fuit, et solitum digito beryllon adederat ignis, summaque Lethaeus triverat ora liquor. spirantisque animos et vocem misit: at illi pollicibus fragiles increpuere manus : "Perfide nec cuiquam melior sperande puellae, in te iam vires somnus habere potest? iamne tibi exciderant vigilacis furta Suburae et mea nocturnis trita fenestra dolis? per quam demisso quotiens tibi fune pependi, alterna veniens in tua colla manu! saepe Venus trivio commissa est pectore mixto fecerunt tepidas pallia nostra vias. foederis heu taciti, cuius fallacia verba non audituri diripuere Noti. at mihi non oculos quisquam inclamavit euntis: unum impetrassem te revocante diem: . . . sed tibi nunc mandata damus, si forte moveris si te non totum Chloridos herba tenet: nutrix in tremulis ne quid desideret annis Parthenie: potuit, nec tibi avara fuit: deliciaeque meae Latris, cui nomen ab usu est, ne speculum dominae porrigat ilia novae: et quoscumque meo fecisti nomine versus, ure mihi: laudes desine habere meas. pelle hederam tumulo, mihi quae praegnante corymbo mollia contortis alligat ossa comis; ramosis Anio qua pomifer incubat arvis, et numquam Herculeo numine pallet ebur; hic carmen media dignum me scribe columna, sed breve, quod currens vector ab urbe legat: HIC TIBVRTINA lACET AVREA CYNTHIA TERRA: ACCESSIT RIPAE LAVS, ANIENE, TVAE. nec tu sperne piis venientia somnia portis: cum pia venerunt somnia, pondus habent. nocte vagae ferimur, nox clausas liberat umbras, errat et abiecta Cerberus ipse sera. luce iubent leges Lethaea ad stagna reverti: nos vehimur, vectum nauta recenset onus. nunc te possideant aliae: mox sola tenebo: mecum eris, et mixtis ossibus ossa teram." haec postquam querula mecum sub lite peregit, inter complexus excidit umbra meos. |

Cynthia's rage, and her last wish

The shades of the dead are real. Death does not end everything. |

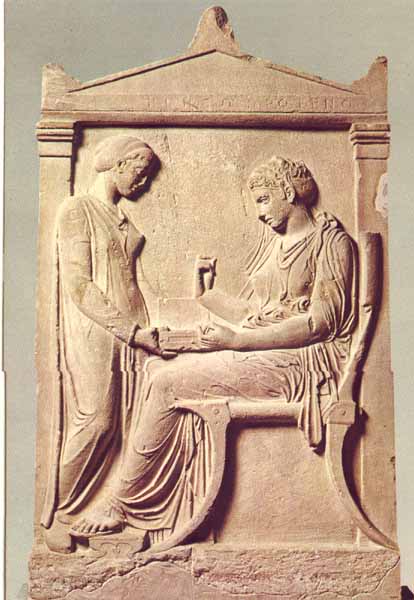

Funeral stele of Hegeso, ca.410-ca. 400 B.C., found in the Kerameikos cemetery in Athens, now in Athens' National Archaeological Museum. A replica has been set up in the Kerameikos. Hegeso takes a last look at her jewels, brought to her by her maidservant. The relief is Greek, not Roman, but conveys the sadness evident in Propertius' poem, written four centuries later.

Quotation for September, 2014

In honor of Apple's introduction of its new iPhone:How Propertius lost his iPhone, er, wax tablets |

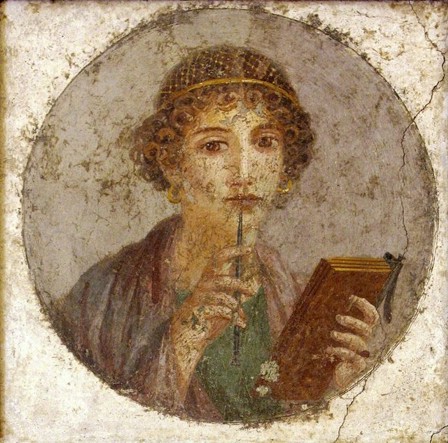

She is arguably the most famous painting from Pompeii. Discovered in 1760, the young lady pondering what to write on her tablets dates from around 50 A.D. She currently resides in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. (Image uploaded to Wikimedia by the Yorck Project, 10,000 Meisterwerke der Malerei.)

Girl with the ancient iPhone

We've known her forever, the young girl staring at us pensively from every Latin textbook, the stylus pressed to her lips as she ponders what words to write on her wax tablets. We don't know who she was. Some have fantasized that she is the poetess Sappho, but in reality she was most certainly a well-to-do young lady of Pompeii, where her portrait, painted around 50 A.D., was found in 1760. Her gold hair net and earrings show her high status.

The wax tablet was the mobile device of its day, ubiquitous like today's iPhone. We can indulge in a bit of fantasy: Did our puella ever lose her tabellae (or have them stolen from her), exposing intimate thoughts written upon them, which are then repeated by raucous strangers? Did she ever walk along composing a letter, and wander absent-mindedly across the via into the path of a speeding chariot, whose driver barely misses her as he is texting on his tablet, too? Did she ever drop her tablet into the latrine? More somberly, we wonder where she was in 79 A.D., when Pompeii was consigned to a long oblivion by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. She would have been a matrona by then, with a family of her own. We hope they got out in time.

Impermanent scribblings

The ancient Roman writing tablet was a slab of wood covered in wax. One wrote on it by scratching with the pointed end of a sharp stylus. Whatever was written could be erased by smoothing over the wax. One end of the stylus was often flat for this purpose. The entire tablet could be scraped clean, so that the writer could start over. A (completely) "scraped tablet" was a tabula rasa, a term we still use today for a clean start. Several tablets could be fastened together to make a little book, and when used for correspondence they could be sealed for security. They were used by merchants for keeping accounts, they were used as social letters, they could be used by poets for first drafts of poems, or by anyone for random scribblings. Final copies were made by writing in ink on rolls of papyrus.

Propertius' mobile device ends up in the wrong hands

Lest we think our musings about the young lady's tablet are farfetched, we have a poem by the Roman poet Propertius in which he describes how his tablets, for which he felt a deep affection and to which he had entrusted his intimate thoughts, were lost or stolen. They were cheaply made, but they were his. He imagines the "miserly" (avarus) merchant who is now using them to keep his records. Propertius sends his serving boy to post a notice "on some column," offering a reward, "for who would not prefer money instead of a block of wood?" He provides his address, in case someone returns them. We do not know if he got them back.

Below, in Latin and English, is the entire poem.

Propertius Elegies III.23Ergo tam doctae nobis periere tabellae,scripta quibus pariter tot periere bona! has quondam nostris manibus detriverat usus, qui non signatas iussit habere fidem. illae iam sine me norant placare puellas, et quaedam sine me verba diserta loqui. non illas fixum caras effecerat aurum: vulgari buxo sordida cera fuit. qualesoumque mihi semper mansere fideles, semper et effectus promeruere, bonos. forsitan haec illis fuerint mandata tabellis: "Irascor quoniam es, lente, moratus heri. an tibi nescio quae visa est formosior? an tu non bona de nobis crimina ficta iacis?" aut dixit: "Venies hodie, cessabimus una: hospitium tota nocte paravit Amor," et quaecumque volens reperit non stulta puella garrula, cum blandis dicitur hora dolis. me miserum, his aliquis rationem scribit avarus et ponit duras inter ephemeridas! quas si quis mihi rettulerit, donabitur auro: quis pro divitiis ligna retenta velit? i puer, et citus haec aliqua propone columna, et dominum Esquiliis scribe habitare tuum. |

My whole life was on those tablets!And so my learned tablets have perished, |

Detail of painting from the Tomb of Menna, Thebes (Egypt), ca. 1422-1411 B.C. Papyrus plants with a cat stealing eggs from water bird nests. (Image uploaded to Wikimedia by Rainer Zenz for the Yorck Project, 10,000 Meisterwerke der Malerei.)

Quotation for August, 2014

Alexander the Great and a camel; Irbil: crossroads of ancient and modern worlds |

"Restored house facades along the southern perimeter of the Citadel of Arbil (Iraq)." From Wikipedia, originally posted to Flickr by Jim Gordon, created October 14, 2005. Irbil may be the world's oldest continuously inhabited city. Near Irbil is Gaugamela, the site of Alexander's defeat of the Persians.

Irbil, civilization's oldest city?

Irbil, present capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, is much in the news, as extremists of the self-styled Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant fight to take control of it and other cities of the Middle East. Situated in a fertile plain at the crossroads of civilizations, Irbil, dominated by its massive citadel, has seen many empires come and go. Irbil, also called Erbil or Hewlêr and known as Arbela in Classical times, claims to be the world's oldest continuously inhabited city, and it certainly is among the oldest, outlasting Ur, Bablylon, Nineveh, and other storied capitals. It has known Hurrians, Gutians, and Akkadians. It was fought over by the Sumerians, and under the Assyrians it was home to a great temple of Ishtar. It was owned by the Medes, who may be the ancestors of today's Kurds. It was conquered by the Persians, who in turn were conquered by Alexander the Great. The Romans made it the capital of the Roman province of Assyria.

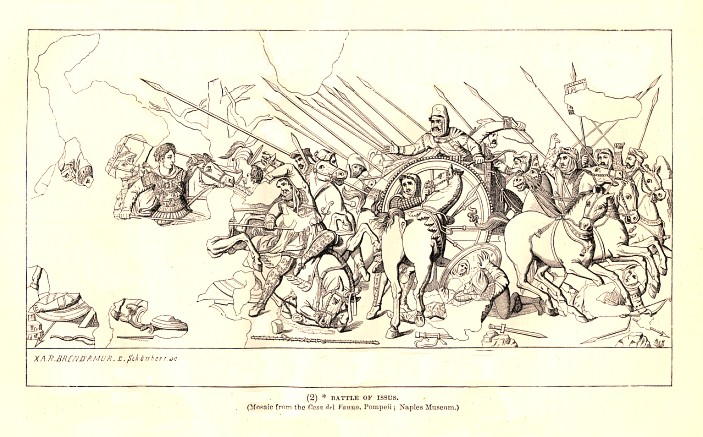

Alexander definitively defeated the Persian king Darius near Irbil at Gaugamela in 331 B.C. Outnumbered by the Persians, whose most fearsome weapon was the chariot fitted with attached scythes that cut down anyone in their path, Alexander cleverly drew off Darius' right and left wings in vain pursuit of his own left and right wings, maneuvering the Persians into uncleared ground where their cavalry could not operate efficiently and making a clear path to attack up the middle. These tactics were similar to those he previously employed against Darius at the battle of Issus, in present-day Turkey.

A very pampered camel

Plutarch, in his Parallel Lives of eminent Greeks and Romans, was fond of enlivening his biographies with gossipy anecdotes. In his life of Alexander, he tells a charming story about the etymology of the place name "Gaugamela," which supposedly meant "the camel's house." He tells how "an ancient king" (he provides no ethnicity) escaped his enemies on a "swift camel." The word translated here as "swift" is dromás, "a runner," hence a kámelos dromás is a camel bred for running fast — the origin of our word dromedary! The king rewarded the camel with her own house, and income and care for life. Plutarch goes on to describe Alexander's preparations for battle, consisting of secret holy rites and animal sacrifices. But of course it was tactics, not mysterious rites, that won the war.

Below, in Greek and English, is Plutarch's story about the camel and Alexander's ritual preparations. For more about Irbil and the excavations that are taking place there, see "Erbil Revealed" by Andrew Lawler in the September/October 2014 issue of Archaeology, available online on the website of the Archaeological Institute of America.

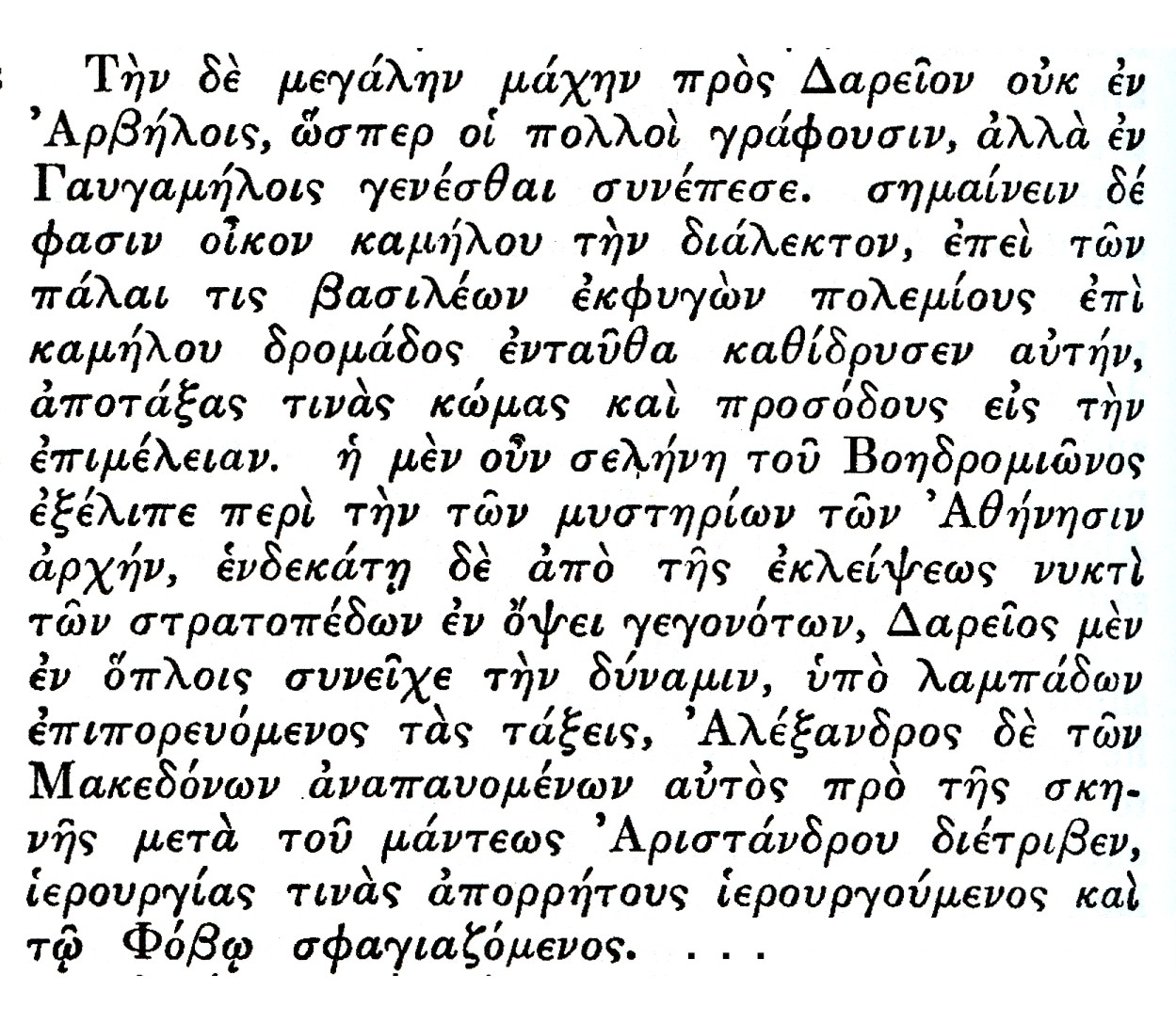

Plutarch, Alexander 31.3-4

|

Why was it called Gaugamela?The great battle against Darius took place not at Arbela, as most write, but at Gaugamela. They say that the name means "house of the camel," because one of the ancient kings, fleeing his enemies on a swift camel, gave her a home there, assigning certain villages and revenues for her care. Well, the moon, in the month Boedromion, had an eclipse around the beginning of the Mysteries at Athens, and on the eleventh night after the eclipse, the armies being within sight of each other, Darius kept his forces under arms, and reviewed the ranks by torchlight. But Alexander, while his Macedonians slept, spent the time in front of his tent with the seer Aristander, performing certain secret holy rites and making sacrifices to Fear. . . . |

Darius at the battle of Issus, mosaic from the Casa del Fauno, Pompeii. (Image from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Quotation for July, 2014

Odysseus in Arkansas: Meeting new acquaintances far from the sea (Odyssey Book 11) |

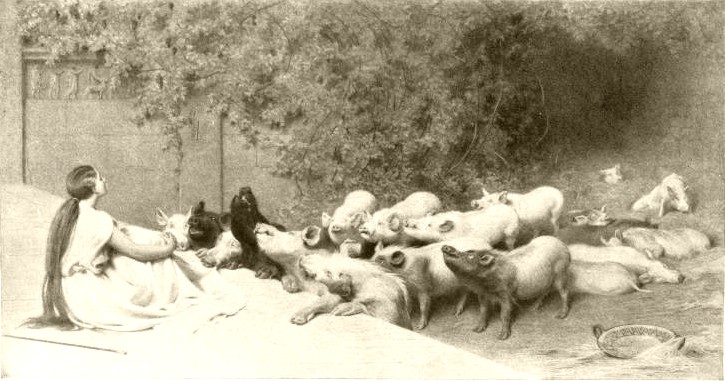

Briton Rivière, Circe and the Companions of Ulysses, 1871. The original painting by Rivière has dropped from sight, but this reproduction, in both black and white and colorized versions, is widely available on the Internet. Rivière was well known for his paintings of animals. Circe directed Odysseus (Latin "Ulysses") to go to the Underworld to consult the seer Teiresias about his future.

Prequels and sequels to the Trojan War

In the movies, it's called a franchise. Audiences are eager to know the further adventures of favorite heroes and heroines. After the initial blockbuster, there are sequels. What new bad guys were vanquished by Superman? What happened to Harry Potter after he grew up and had a family? Then come the "prequels," telling what happened before the main story. How did Spiderman get his spider powers? Who was Darth Vader before he became Darth Vader?

Ancient Greek oral epic, the popular equivalent of our movies and cable TV, was no different. Homer's Iliad and Odyssey are, for us, the story of the Trojan War and its aftermath, but there were other poems called the Epic Cycle, composed by various singers, that told what happened to Paris and Helen, Odysseus and Penelope, before and after the events of the two great epics. The Cypria, for example, told the story of the Judgment of Paris, in which the Trojan prince is awarded Helen as a prize by Aphrodite for declaring her the most beautiful goddess, thus starting the Trojan War. Another, the Nostoi ("Returns") told the adventures of Agamemnon, Menelaus, Diomedes, and other Greek heroes after the war. Other "franchises" were the Theban Cycle of epic poems about Oedipus, Antigone, and the Seven Against Thebes, the saga of Jason and the Argonauts, and stories about Theseus and Heracles. All these epics are lost, but the stories are known from short digests, from shorter poems like the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod's Theogony and Works and Days, and from the plays of Athenian dramatists who drew on the now lost epics for inspiration. Vergil's Latin Aeneid is another sequel to the Iliad.

Odysseus' adventures with his oar foretold by Teiresias in the Underworld

The final poem in the Epic Cycle was the Telegony, which told of Odysseus' later adventures and death. After disposing of the Suitors, Odysseus travels far inland, and dies, wounded in a fight with Telegonus, his own son by the goddess Circe, who does not recognize his father (a situation similar to Oedipus' killing of Laius). Bizarrely, Telegonus marries Penelope and Telemachus, Odysseus' son by Penelope, marries Circe.

We know the outline of the Telegony from Book 11 of the Odyssey. Odysseus and his men disembark on the island of Aeaea, where the goddess Circe turns the men into pigs (Book 10, illustrated above). Returning the men to their human form, Circe wines and dines them for a year. Finally, she lets them leave, but Odysseus must go to the Underworld to ask the shade of the Theban seer Teiresias to foretell his fate. In one of the great ghost stories of all literature, Odysseus visits the land of the dead. Teiresias tells Odysseus that after he kills the Suitors, he must journey far inland carrying an oar, until he meets a people who know nothing of the sea, and mistake the oar for a paddle-shaped winnowing fan, used by farmers to separate grain from chaff. Then he is to perform a sacrifice to Poseidon, return home, and make offerings to all the gods. Then he is to expect death "from the sea." This incident, used by both Aeschylus and Sophocles in (lost) plays, is often interpreted as a reference to Telegonus, who kills his father with a spear tipped with a fish bone.

Far from the sea, my maritime hat is unfamiliar

I recently had my own Odyssean moment, carrying a symbol of the sea into the grain lands of inland America. I was attending a convention of the National Railway Historical Society in Springdale, Arkansas. We went on rail excursions and took plenty of pictures. We were guests of the Arkansas and Missouri Railroad, which serves a thriving industrial area of the Ozarks, in a landscape of deep wooded valleys and fields dominated by towering grain elevators. As usual, I wore a broad-brimmed sun hat that I bought on the aircraft carrier John F. Kennedy when she visited New York during Fleet Week of 2005, as she made her farewell tour just before decommissioning. Embroidered on its crown are the initials "JFK" in the shape of an aircraft carrier viewed head-on, with planes taking off from her deck (see below). The "J" forms the starboard side, with its "island" or control structure, the "K" is the overhanging port side, and the "F" is the flat deck in the middle. I am accustomed to perfect strangers complimenting my attire, often just with a "Nice hat!" but sometimes with a nostalgic comment like "I served two years on that ship!" So in Arkansas I was surprised when a puzzled fellow excursionist asked "What does 'JFK' mean?" I explained, more or less to the stranger's satisfaction, the maritime origins of my hat.

Suddenly, I was Odysseus with his oar. I, too, carried a symbol of the sea to a land of grain, far from oceans and ships. Those who fill Springdale's granaries use John Deere combines rather than the winnowing fan. But what had been for me just a quaint myth assumed an immediate reality.

Below, in Greek and English, are the words of Teiresias's prophecy to Odysseus describing his ultimate fate.

Odyssey 11.119-137

|

Teiresias foretells Odysseus' fate". . . But when you have killed the suitors in your halls |

"JFK" initials in the shape of an aircraft carrier, embruidered on a hat. Jet planes take off from the deck, and a birdlike helicopter hovers in the upper left corner.

Quotation for June, 2014

For the 70th anniversary of D-Day, the departure of the Athenian fleet for Syracuse, described by Thucydides |

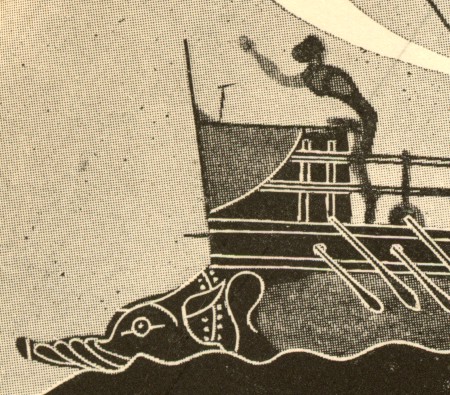

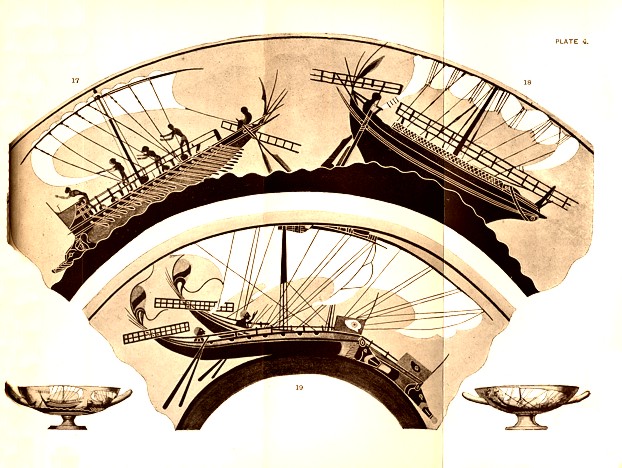

Illustration adapted from Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships , 1895. (Top) war ship and merchant ship, about 500 B.C.. From a painted vase found at Vulci in Etruria, in the British Musuem. (Bottom) two war ships, about 500 B.C. From a painted vase by Nicosthenes, found at Vulci in Etruria, in the Louvre.

Two gallant flotillas, at Normandy on D-Day and in ancient Athens

An enormous force of ships and men, provided with every modern armament, spearheading history's greatest invasion, meticulously planned over many months. The result is a bloody apocalypse, thousands of dead littering the beach, invaders drowned in their tanks before they can reach the shore, landing craft exploding on hidden mines. Somehow the planning went terribly wrong.

This June we commemmorate the 70th anniversary of the Allied landing in Normandy in World War II. Of the five landing beaches along the north coast of France, Omaha Beach, assaulted on June 5, 1944, has assumed mythic proportions for its scene of catastrophe. Bomber runs meant to soften defenses missed their mark, landing craft landed at the wrong spot, infantry burdened by overloaded backpacks were cut down as they disembarked. Although the Nazis believed the invasion would take place at the narrower channel at Calais, the entire coast had been well fortified by the efforts of Erwin Rommel, known as the Desert Fox for his earlier exploits in North Africa. The first waves of soldiers were mowed down as they came ashore, in a self-described "suicide mission." Over 9000 military dead, mostly from the Normandy invasion, are buried in the American cemetery overlooking Omaha Beach.

Ultimately, the Allies clawed their way ashore, and World War II ended with an Allied victory.

But we are put in mind of another gallant naval invasion, begun with high hopes and a belief in the invaders' invincibility, which took place almost 2500 years ago. This was the disastrous expedition of the Athenians against the Sicilian city of Syracuse in the waning years of the Peloponnesian War.

The Athenian expedition to Syracuse

The fifth century B.C. in ancient Greece is bookended by two great wars. The Persian Wars, chronicled by Herodotus, led to the hegemony of Athens and the foundation of the Athenian Empire. The Peloponnesian War, between Athens and allied city-states on the one hand, and Sparta (Athens' erstwhile ally) and cities allied with Sparta on the other, described magnificently by Thucydides, led to the dissolution of that empire. Athens survived as a center of learning, science, and philosophy, but her reign as a "global" political power came to an end.

The fleet sets out in a party atmosphere

The expedition to Syracuse began with an appeal by the Sicilian city of Segesta to Athens in 416 B.C. for aid in its war with another Sicilian city, Selinus. There was also an appeal from the Leontines, who were at war with Syracuse, a Sicilian colony of Corinth, a city allied with Sparta and a commercial foe of Athens. The Segestans deceived the Athenians into believing that they had great wealth with which they could finance an invasion. Sicily was of little importance to Athens, whose interests lay in the older Greek world of the eastern Mediterranean. But some young Athenian leaders saw an opportunity to increase the power and empire of Athens, with attendant greater glory. These leaders included the charismatic Alcibiades, perhaps best known to us as a character in Plato's Symposium, in which he tries drunkenly to seduce Socrates. The older, cautious general Nicias opposed the idea, and pointed out the enormous size of the force that would be needed, hoping to dissuade the Athenian people from the venture. The ploy backfired. The Athenians happily voted to send one hundred triremes instead of the sixty originally asked for. Nicias, Alcibiades, and Lamachus were appointed leaders. The fleet departed with much celebration, the ships racing each other out of the harbor as crowds onshore cheered.

Catastrophe

Things went bad quickly. Alcibiades was recalled to Athens on a charge, perhaps true, perhaps unwarranted, of mutilating sacred statues of Hermes and celebrating a mock version of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Lamachus advised immediately attacking Syracuse, but cautious Nicias dithered and wasted time, building fortification walls and fighting small skirmishes, giving Syracuse time to regroup and seek help from Corinth and Sparta. Alcibiades avenged himself by defecting to Sparta, advising the Spartans on their conduct of the war. More ships arrived from Athens as reinforcements, to no avail. Finally, the Athenian ships, with their long prows suited for fighting in open water, were penned in Syracuse harbor by the shorter, stouter ships of their opponents. The remnants of the Athenians tried to escape overland, but most were killed or sold into slavery. A few were allowed to escape because of their ability to recite favorite selections from the plays of Euripides.

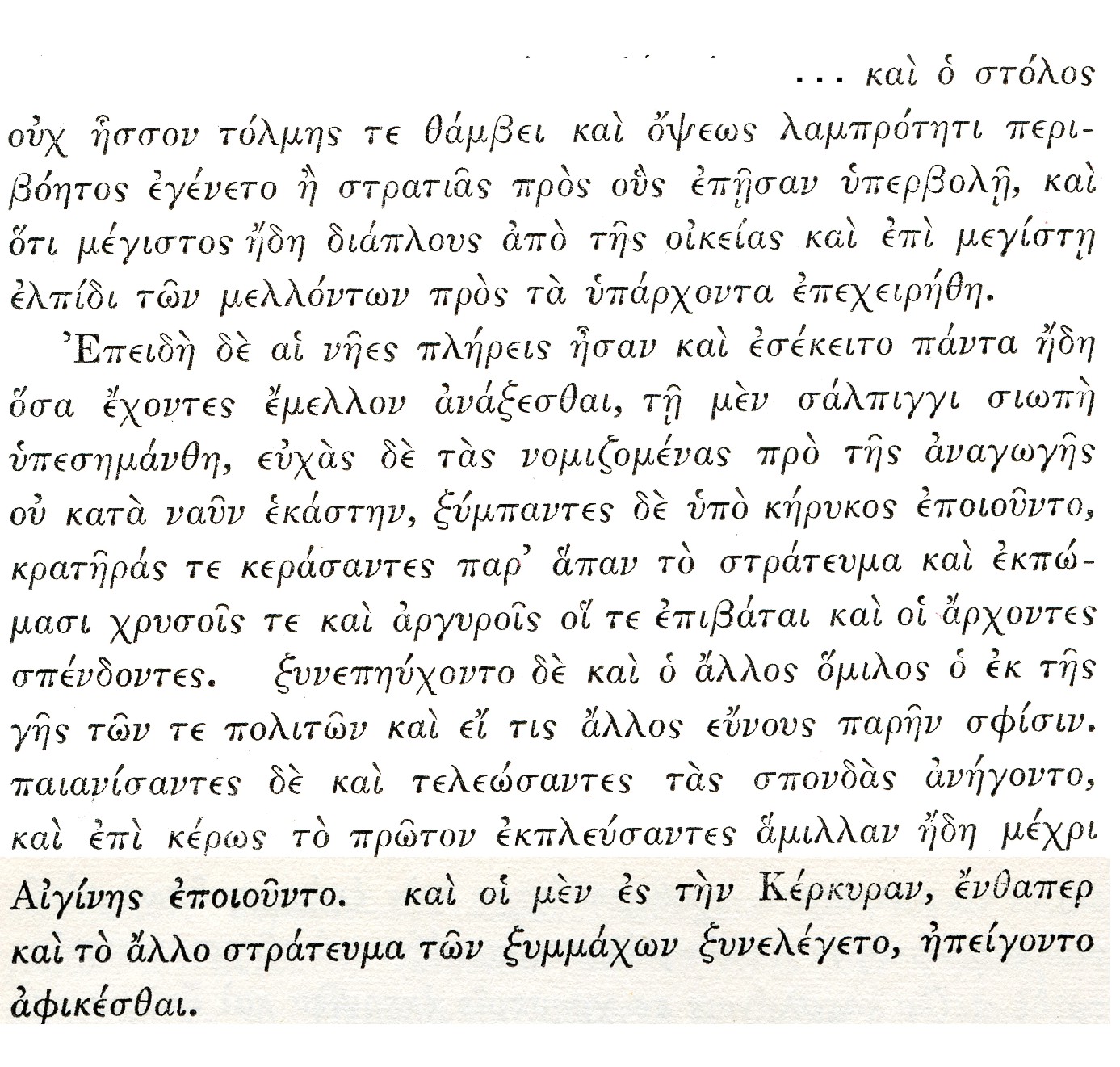

Below, in Greek and English, is Thucydides' description of the splendid departure of the Athenian fleet.

Theucydides Histories 6.31-32

|

A dazzling display by the Athenian navy. . . Indeed, the expedition became famous not less for the wonder of its boldness and the splendor of its appearance than for the superiority of its army in comparison to those whom they attacked, and because it was their longest voyage away from home and was attempted with the greatest hopes in comparison to their resources.When the ships were fully manned and everything was on board with which they intended to set sail, the trumpet commanded silence, and all offered prayers customary for putting out to sea, not ship by ship but all together led by a herald, and wine-bowls were mixed throughout the force and libations were offered in gold and silver drinking cups by the fighting men and officers. The rest of the crowd on shore joined in their prayers, as well as citizens and anyone else present who wished them well. Concluding their hymn and finishing their libations, they put out to sea, sailing out in a column at first, then racing each other as far as Aegina. And so they hurried to reach Corcyra, where the rest of the force was gathering. |

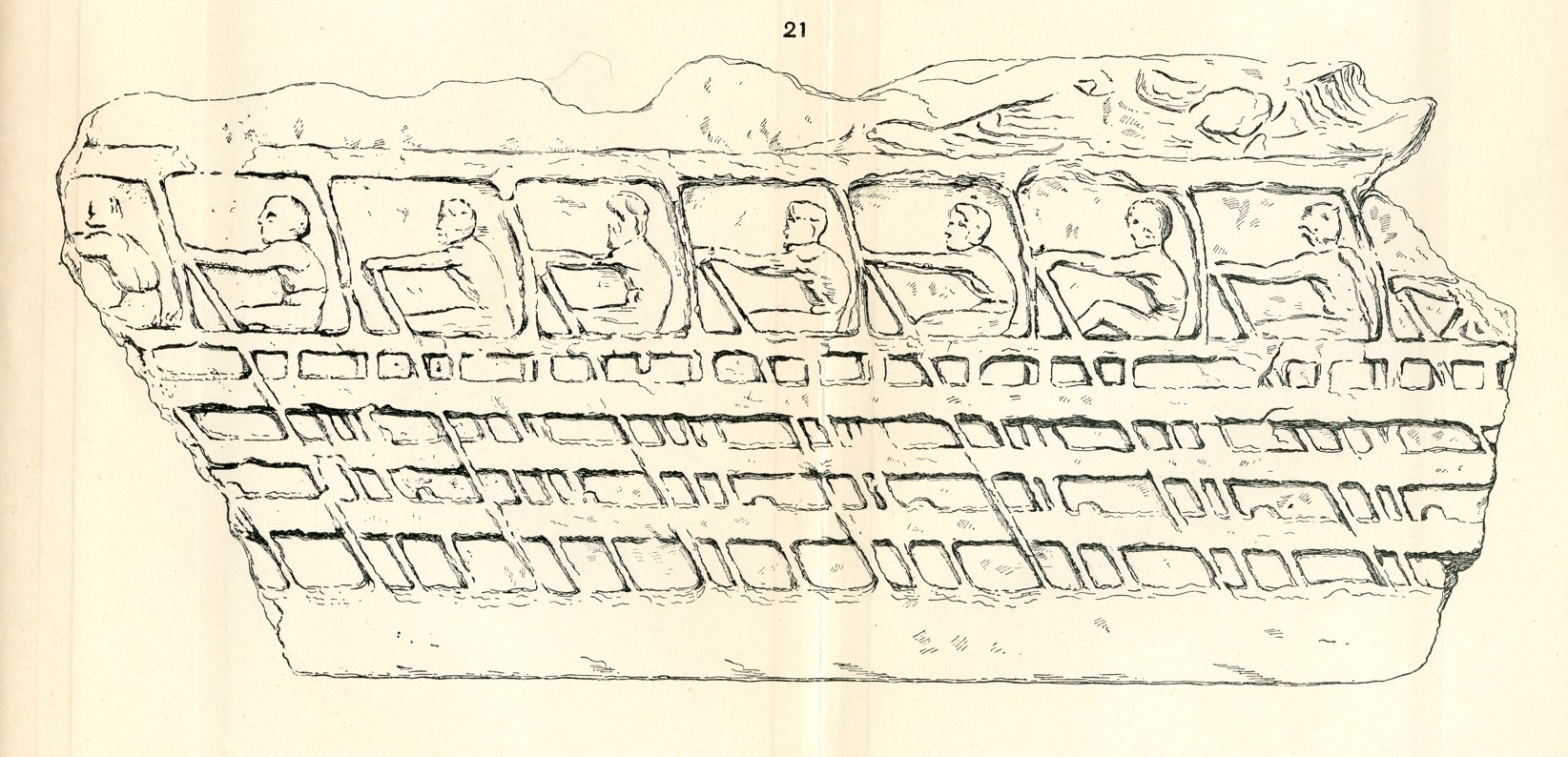

Illustration from Cecil Torr, Ancient Ships , 1895. Waist of a war ship, about 400 B.C. From a fragment of a relief found on the Acropolis at Athens, in the Acropolis Museum. drawn from a cast.

Quotation for May, 2014

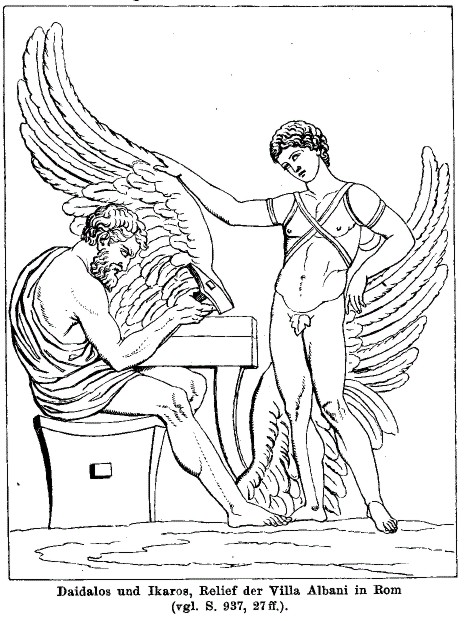

For the anniversary of Charles Lindbergh's flight, Ovid tells the tale of Daedalus and Icarus |

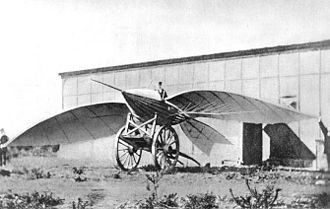

Early attempts to fly by flapping like a bird's wings. (Top) Jean-Marie LeBris, Albatros II, 1868; (bottom) Otto Lilienthal, Ornithopter, 1894.

Aviation's origins — maybe older than we think

On May 20, 1927, Charles Lindbergh took off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island for the first solo non-stop flight across the Atlantic, landing at Le Bourget Field in Paris on May 21. Others, in fact, had crossed the Atlantic by air (or tried to), with a copilot, or with stops, or flying a shorter route (say, Newfoundland to Ireland), and in 1924 four aircraft of the U.S. Army Air Service set off on the first round the world flight (three completed the journey). Of course, the modern history of flight goes far back beyond the Wright Brothers' first controlled powered heavier than air flight in 1903. Designs that allow humans to take to the air go back centuries, perhaps millennia, many taking the form of an ornithopter, which achieves lift by flapping like a bird. Leonardo da Vinci designed such a machine, and Otto Lilienthal's 1894 version is depicted above. Many have tried to fly by jumping off a tower, often with disastrous or lethal results. The Russian inventor Alexander Lodyguine, who later invented a pre-Edison incandescent light bulb, as a little boy fitted wings to his sister Julia and pushed her off the roof! (She only hurt her ankle. The story was recorded by his wife, my great-aunt Alma.)

But the full story of human flight probably reaches back to the first time a hominid watched a bird. Legends of human flight come from various parts of the world, including India and China. Best known in the Western world is that of Daedalus and Icarus, the inventor who fashioned wings of feathers, wax and twine, and his foolish son who flew too close to the sun so that his wings melted.

Daedalus the master inventor

Daedalus the legendary craftsman was credited with an amazing number of inventions, including lifelike statues, waterworks, and fortresses, not to mention the Cretan labyrinth in which the Minotaur was kept, and the wooden cow built for King Minos' wife Pasiphae so that she could mate with a bull, by whom she gave birth to the Minotaur. Held against his will by Minos, he fashioned the wings by which he and Icarus fled from Crete. The name "Daedalus," related to the stem daidal- meaning "a cunningly wrought work of art," may not have been the actual name of a man but merely descriptive, and one man undoubtedly did not invent all the innovations ascribed to him. But legends and myths often turn out to have more than a core of truth. The Trojan War was considered a fairy tale until the disovery by Schliemann of Troy and Mycenae. Homer describes Hephaestus' golden robot assistants, but we know of actual automata built by Heron of Alexandria and other Hellenistic inventors. As for clever mechanisms, the Antikythera Mechanism of 100 B.C. has proved to be an early computer, a work of such sophistication that it undoubtedly had earlier prototypes. It seems more than likely that at least one curious inventor known as "Daedalus" "The Craftsman," was tempted to imitate the birds.

Icarus the reckless boy

Two major surviving sources for the myth of Daedalus and Icarus are Ovid's Metamorphoses and the Library of Apollodorus. Ovid, as he often does, dwells on the pathos of the story, the worried father and the reckless boy, presented here more as a heedless child, playing with the feathers and wax, than as the handsome young man often depicted in art. Ovid describes the wonderment of spectators, who think the flying men must be gods. Following his loss of Icarus, Daedalus is confronted by a partridge, emblematic of Daedalus' darker side. The bird was the transformed form of his nephew Perdix, son of his sister, whom Daedalus murdered out of jealousy because of Perdix' skill as an inventor. Apollodorus (who calls the nephew "Talos," with a mother named "Perdix") tells us that escape from the charge of murder was Daedalus' reason for being in Crete in the first place (Apollodorus III.xv.8).

Below, in Latin and English, are verses 183-220 from Book 8 of Ovid's Metamorphoses, which describe how Daedalus made the wings, layering the feathers from smallest to largest, "like a set of Pan-pipes," and his worries, which turned out to be well-founded, about his son.

OvidMetamorphoses 8.183-220 . . .Daedalus interea Creten longumque perosus exilium tactusque loci natalis amore clausus erat pelago. "terras licet" inquit "et undas obstruat: et caelum certe patet; ibimus illac: omnia possideat, non possidet aera Minos." dixit et ignotas animum dimittit in artes naturamque novat. nam ponit in ordine pennas a minima coeptas, longam breviore sequenti, ut clivo crevisse putes: sic rustica quondam fistula disparibus paulatim surgit avenis; tum lino medias et ceris alligat imas atque ita conpositas parvo curvamine flectit, ut veras imitetur aves. puer Icarus una stabat et, ignarus sua se tractare pericla, ore renidenti modo, quas vaga moverat aura, captabat plumas, flavam modo pollice ceram mollibat lusuque suo mirabile patris impediebat opus. postquam manus ultima coepto inposita est, geminas opifex libravit in alas ipse suum corpus motaque pependit in aura; instruit et natum "medio" que "ut limite curras, Icare," ait "moneo, ne, si demissior ibis, unda gravet pennas, si celsior, ignis adurat: inter utrumque vola. nec te spectare Booten aut Helicen iubeo strictumque Orionis ensem me duce carpe viam!" pariter praecepta volandi tradit et ignotas umeris accommodat alas. inter opus monitusque genae maduere seniles, et patriae tremuere manus; dedit oscula nato non iterum repetenda suo pennisque levatus ante volat comitique timet, velut ales, ab alto quae teneram prolem produxit in aera nido, hortaturque sequi damnosasque erudit artes et movet ipse suas et nati respicit alas. hos aliquis tremula dum captat harundine pisces, aut pastor baculo stivave innixus arator vidit et obstipuit, quique aethera carpere possent, credidit esse deos. . . |

Daedalus has a sense of foreboding. . .Daedalus, meanwhile, detesting Crete and his long exile, and moved by love of his native land, was shut in by the sea. "Let Minos," he said, "obstruct land and waves, the sky lies open; we will go that way. Let him be master of all things, he is not master of the air." He spoke, and devotes his mind to unknown arts and remakes nature. For he places feathers in a row, beginning with the smallest, with long next to short, so that you would think they had grown upon a slope. Just so a rustic pan-pipe rises gradually with unequal reeds. Then with thread and wax he fastens them at the middle and bottom and thus arranged he bends them with a slight curve, to imitate real birds. The boy Icarus stood next to him and ignorant that he was handling his own danger, with beaming face now caught at feathers moved by a wandering breeze, now softened the yellow wax with his thumb, and by his play impeded his father's wondrous work. When the final touches had been put on the undertaking, the artisan himself balanced his body on twin wings and hung in the breeze made by their motion. Then he instructed his son: "I warn you to run a middle course, Icarus," he said, "lest, if you go lower, the waves weigh down the feathers, if higher, lest the fire burn them. Fly between both. And I command you not to go off looking at Bootes or Helice or the drawn sword of Orion but with me as leader take your course." Simultaneously, he imparts the precepts of flight and fits unaccustomed wings on shoulders. During the work and admonitions, the old man's cheeks were wet, and his fatherly hands trembled. He gave kisses to his son, never again to be repeated, and lifted up by his wings he flew on ahead, but feared for his companion, like the bird who has led forth her tender progeny from the high nest into the air. He exhorts his son to follow and instructs him in those pernicious skills, as he moves his own wings and looks back at his son's. Now some man angling for fish wih quivering rod, or a shepherd leaning on his staff or a plowman on his plow handle saw them and, standing stupefied, thought those who could navigate the air were gods. . . |

Daedalus and Icarus. (Image from Roscher, Ausführliches Lexikon der Griechischen und Römischen Mythologie, 1890.)

Quotation for April, 2014

Ovid, in his Fasti, discusses the origin of the name "April" |

Venus on a sea shell, from the Casa dei Venus, Pompeii. (Photo by Stephen Haynes, from Wikipedia.) The month of April was sacred to Venus, as were the myrtile and the rose.

April belongs to Venus

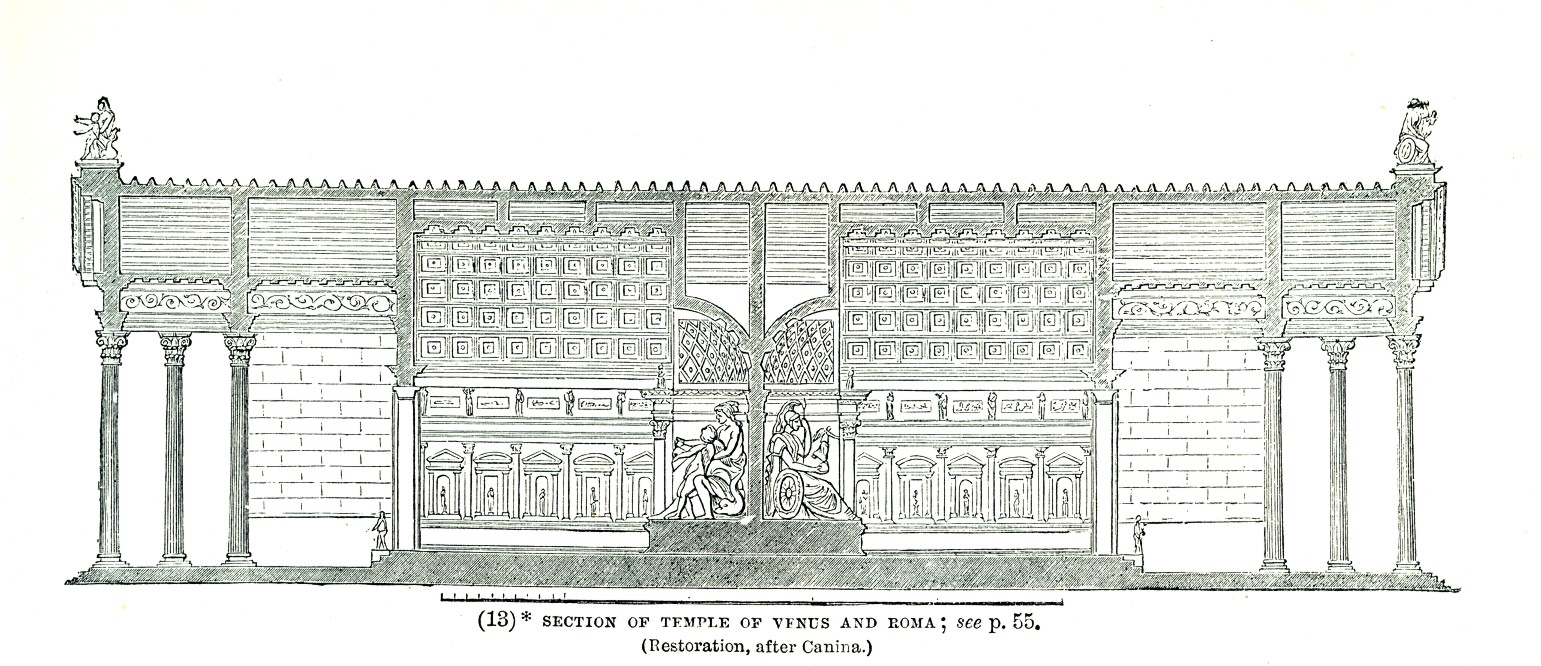

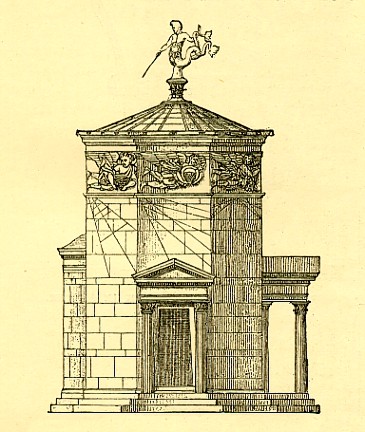

Venus was an old Italian divinity, associated with the bounty of gardens and harvests. She became identified with the Greek goddess Aphrodite as a goddess of love, sex, fertility, and prosperity, with all her associated myths, including her birth from the sea, her association with Mars (Greek Ares) the god of war, and her being the mother of the hero Aeneas by the Trojan prince Anchises. Through this last myth, Venus was regarded as the ancestress of the Roman people, especially under the Roman Emperors, as Julius Caesar claimed direct descent from Aeneas (see Vergil's Aeneid). The emperor Hadrian erected an enormous temple to Venus and Rome (now long gone; see the reconstruction at the bottom of this article). The statues of Venus and Roma were placed back-to-back, emphasizing the fact that AMOR is ROMA spelled backwards!

The month of April was sacred to Venus, a time of blossoming and budding of trees and vines. Ovid, in his Fasti, or Roman Calendar, includes a long hymn to Venus in his month of April, celebrating her as not only a goddess of love and fertility, but a giver of all arts, culture, and civilization. He mocks those who would "deprive" Venus of her month of April by deriving the name from aperio "to open," a reference to the "opening up" of buds and the "softening" of the earth after a harsh winter. Of course, every line of his poem actually proves the truth of the (probably accurate) derivation of the name, as he rhapsodizes over the budding trees, the mating animals, and the calm seas that invite the mariner locked up all winter by storms.

A hymn to Venus

Below, in Latin and English, are lines 85-132 of Book IV of Ovid's Fasti. Venus' injury, referred to in line 120, was caused by the Greek hero Diomedes. The conquest of two goddesses by a "Trojan judge" is, of course, the Judgment of Paris, in which the Trojan prince judged Aphrodite more beautiful than Hera or Athena and received Helen of Troy as his reward, thus starting the entire Trojan War. Venus is the "grand-daughter-in-law of Assaracus," who was the grandfather of Anchises, by whom she became the mother of Aeneas.

OvidFasti IV.85-132 .Quo non livor adit? sunt qui tibi mensis honorem eripuisse velint invideantque, Venus. nam quia ver aperit tunc omnia, densaque cedit frigoris asperitas, fetaque terra patet, Aprilem memorant ab aperto tempore dictum, quem Venus iniecta vindicat alma manu. illa quidem totum dignissima temperat orbem; illa tenet nullo regna minora deo, iuraque dat caelo, terrae, natalibus undis, perque suos initus continet omne genus. illa deos omnes (longum est numerare) creavit; illa satis causas arboribusque dedit; illa rudes animos hominum contraxit in unum et docuit iungi cum pare quemque sua. quid genus omne creat volucrum, nisi blanda voluptas? nec coeant pecudes, si levis absit amor. cum mare trux aries cornu decertat; at idem frontem dilectae laedere parcit ovis. deposita sequitur taurus feritate iuvencam, quem toti saltus, quem nemus omne tremit. vis eadem, lato quodeumque sub aequore vivit, servat et innumeris piscibus implet aquas. prima feros habitus homini detraxit: ab illa venerunt cultus mundaque cura sui. primus amans carmen vigilatum nocte negata dicitur ad clausas concinuisse fores, eloquiumque fuit duram exorare puellam, proque sua causa quisque disertus erat. mille per hanc artes motae; studioque placendi, quae latuere prius, multa reperta ferunt. hanc quisquam titulo mensis spoliare secundi audeat? a nobis sit furor iste procul. quid, quod ubique potens templisque frequentibus aucta, urbe tamen nostra ius dea maius habet? pro Troia, Romane, tua Venus arma ferebat, cum gemuit teneram cuspide laesa manum caelestesque duas Troiano iudice vicit (a! nolim victas hoc meminisse deas!), Assaracique nurus dicta est, ut scilicet olim magnus Iuleos Caesar haberet avos. nec Veneri tempus quam ver erat aptius ullum vere nitent terrae, vere remissus ager, nunc herbae rupta tellure cacumina tollunt, nunc tumido gemmas cortice palmes agit. et formosa Venus formoso tempore digna est, utque solet, Marti continuata suo est; vere monet curvas materna per aequora puppes ire nec hibernas lam timuisse minas. . . |

April is yours, O Venus.. How far will envy not go? There are those who wish to snatch from you the honor of the month and spite you, Venus. For since spring opens all things, and the hard rigidity of frost recedes, and the fertile earth lies exposed, they say that April is named for the season of opening [aperio], a month that bountiful Venus, laying her hand upon it, claims as her own. She deservedly regulates the entire world, she rules a kingdom second to no god, she gives laws to heaven, earth, and her native waves, and through her initiative she preserves every species. She created all the gods (it were long to enumerate them); she gave their origins to the sowed crops and trees; she brought together the uncivilized minds of men and taught them to join each with his mate. What creates the entire species of birds, if not alluring pleasure? Nor would cattle come together, if lighthearted love were absent. The ferocious ram contends with horns against another male, but forbears to injure the forehead of a beloved ewe. The bull lays aside his fierceness to follow the heifer, he before whom every pasture, every grove trembles. The same force preserves whatever lives beneath the broad sea and fills the waters with innumerable fish. That force removed from man his savage appearance, from it came civilized clothing and attention to cleanliness. A lover is said to have been the first to sing a wakeful song at closed doors of one who has denied him nightly entrance. Eloquence it was to persuade the hard-hearted girl, and every man became skilful in pleading his own case. A thousand arts have been set in motion by this goddess. By eagerness to please, it is said that many inventions that before lay hidden have been discovered. Who would dare to despoil her of her title to the second month? Let that madness be far from us. Also, while everywhere she is powerful and honored with crowded temples, nevertheless in our city the goddess has greater authority. For your Troy, o Roman, Venus bore arms, when she groaned, injured by a spear in her delicate hand, and she defeated two divinities by the verdict of a Trojan judge (a! would that the defeated goddesses had not remembered this!) She was called the grand-daughter-in-law of Assaracus, so that one day great Caesar would have Julian forebears. Nor for Venus was any season more fitting than spring. In spring the earth glistens, in spring the fields are soft. Now the plant blades thrust their tops through the burst soil; now the vine-shoot pushes its buds through the swelling bark. Lovely Venus is worthy of the lovely season, and as she is accustomed, is joined with her Mars. In spring she bids the curved ships to go across her maternal sea and not fear the threats of winter. . . |

Section through the Temple of Venus and Roma built by Hadrian, based on the restoration by Canina. Construction was begun in 121 A.D., finished under Antoninus Pius in 141. Probably destroyed by earthquake in the 9th century, rebuilt as a church around 850. Only ruins remain today. (Illustration from Seyffert, A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.)

Quotation for March, 2014

Vladimir Putin Among the Hyperboreans:

|

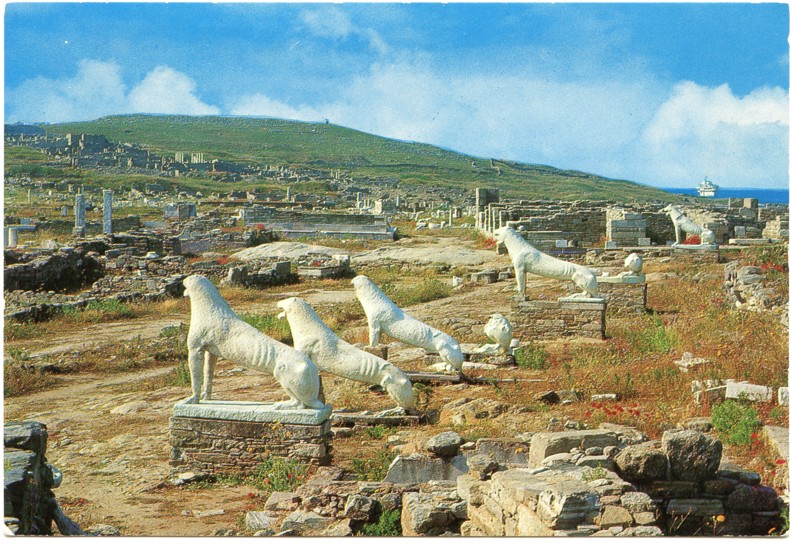

The Terrace of the Lions at Delos was dedicated to Apollo by the people of Naxos before 600 B.C. Of a dozen or so lions, only seven remain in place today. One, removed by the Venetians, is to be found today by the main gate of the Venetian Arsenal. (Illustration froma a postcard.)

Crimea, Scythian gold, and the mythic North

Vladimir Putin's seizure of Crimea from Ukraine and its subsequent annexation by Russia put the Black Sea on the world's radar screen. But this is just the latest chapter in a saga of migrations, conquests, and shifting populations that stretches for millennia across Eurasia. In antiquity large swaths of territory were controlled by the Scythians, of Iranian origin, famed today for the spectacular gold jewelry, silver, and other objects found in locations from Afghanistan and Iran to Crimea and Romania. Their influence may have reached China and Japan. Their western territory, including parts of today's Ukraine and northeastern Balkans, was inhabited by the related Sarmatians. The Roman poet Ovid, lamenting his exile in frozen Tomis on the Black Sea (modern Constanţa, Romania) describes living with Sarmatians, Bessi, and Getae, as well as Greek colonists. In the thirteenth century, the Mongols under Ghengis Khan and his successors ruled an empire that stretched from China across Asia and Russia to eastern Europe. In 1853-1856 Russia lost the Crimean War against an alliance including the Ottoman Empire, France, and Britain, a war immortalised in Tennyson's "The Charge of the Light Brigade." Russia later rebuilt its naval base at Sebastopol.

North of all known tribes, the Greeks believed, lived the Hyperboreans, situated "beyond Boreas, the North Wind", living long lives of bliss where the sun never sets. Every year, the Hyperboreans brought offerings of first fruits to the temple of Apollo on Delos. Perhaps word had arrived of the long summer Arctic days, but there was no awareness that in winter the sun never rises!

The Hyperborean Maidens' mission to Delos

Delos, rocky little island, cult sanctuary since pre-Greek antiquity, was known as the birthplace of Apollo and was sacred to him. It became the center of the Delian League, the confederacy of Greek states formed after the defeat of the Persians. Later, the Delian League morphed into the Athenian Empire, when its headquarters were moved to Athens. Legend had it that the Hyperboreans originally sent offerings of wheat sheaves to Apollo in care of two young women, whom Herodotus names as Hyperoche and Laodice. To protect them, several young men went along. The young people never returned, but died in Delos. So the Hyperboreans changed their method, sending their offerings to Delos by relay, passing them first to the Scythians, thence by stages to Dodona and Euboea, and eventually to Delos, a practice followed in Herodotus' day. To honor the memory of the Hyperboreans, young Delian women, before marriage, as well as young men, offer locks of hair at their tomb before the temple of Artemis. Herodotus also tells a story of two other Hyperborean maidens, Arge and Opis, who came before Hyperoche and Laodice. In this version, the latter pair brought offerings to Eileithuia, goddess of childbirth. Callimachus, from whom we get our Quotation of the Month, tells yet another version.

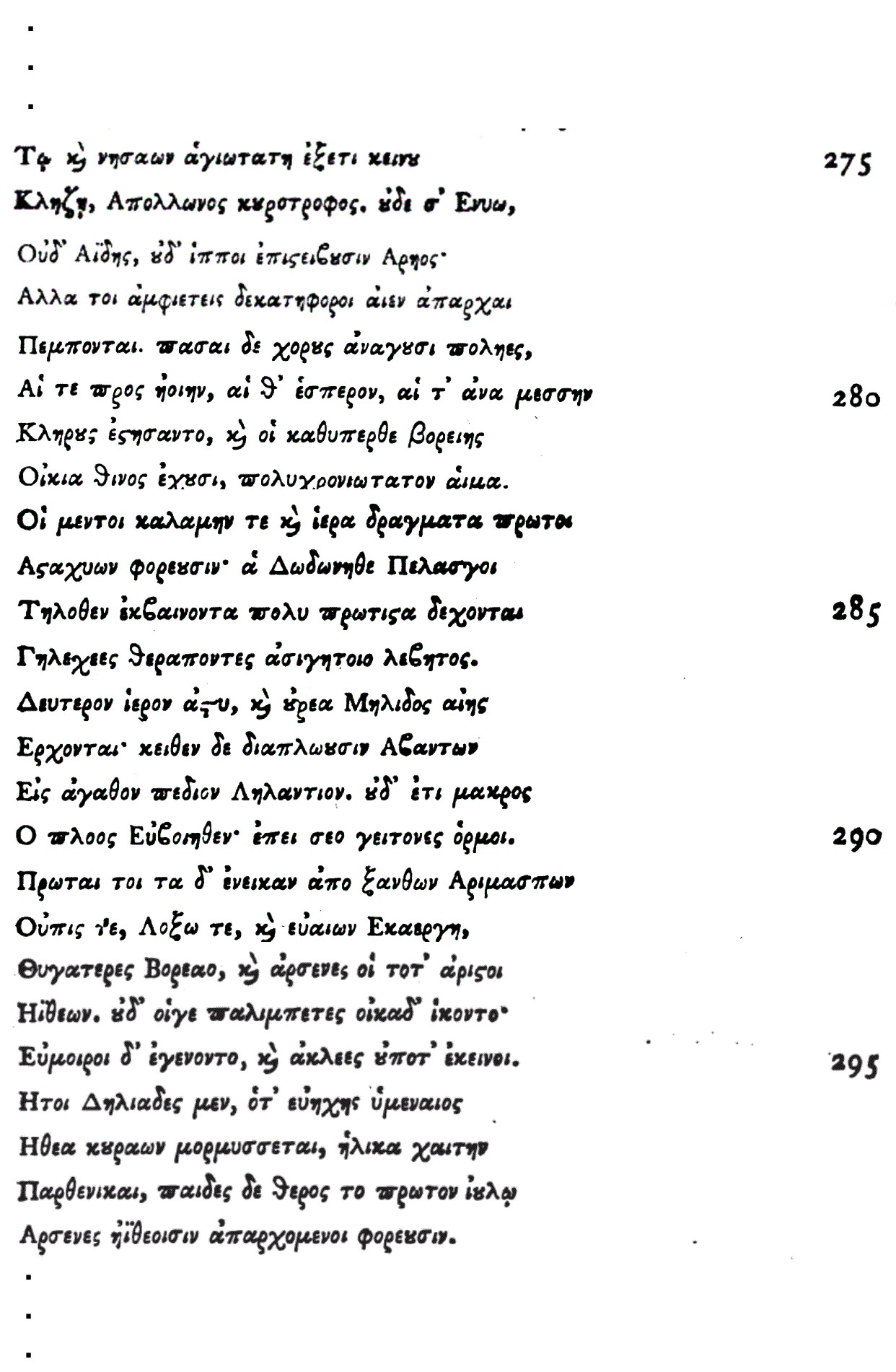

Callimachus' Hymn to Delos

The Alexandrian poet Callimachus (ca. 310-ca.240 B.C.), in his Hymn to Delos, tells much the same tale as the "Delian" portion of the ancient Homeric Hymn to Apollo. Leto searches for a place to give birth to her son Apollo (and, not emphasized, her daughter Artemis). Leto must escape the wrath of Hera, whose threats and persecution against potential birthing sites are elaborated by Callimachus. He also makes Delos a wandering island, rooted in no place. Only the spunky little island, a wanderer like herself, ignores the threats and accepts Leto. Apollo is born, fixes Delos to the sea bed, and founds a temple to which all cities bring their first fruits and their choral song, including the Hyperboreans, "that long-lived race." He names the Hyperborean maidens as Upis, Loxo, and Hecaerge. Before a wedding, the young girls dedicate a lock of hair to the Hyperborean maidens, and the young men dedicate their first beards to the lost Hyperborean youths.

Here, in Greek and English, is Callimachus' telling of the legend of the relay of gifts from the Hyperboreans to Delos. Delos is addressed directly in the poem. Enyo is the goddess of war, companion of Ares, god of war. The "never-silent cauldron" in the temple at Dodona may have been a resonant bowl, used as a gong. The Arimaspians, another legendary people, seem to be used interchangeably with the Hyperboreans.

Note: The Greek text may look a little odd; it is taken from an edition by H.W. Tytler of 1793, with its quaint old-fashioned ligatures: Omicron + upsilon is printed as a single character, with the "u" above the "o"; sigma + tau is likewise represented as one character, like a flat-topped sigma; the letter pi often looks like a Roman "w" with a flat top; beta unravels into two stacked loops; "kai" ("and") is abbreviated to a kappa with an affixed squiggle. ("The Works of Callimachus, translated into English verse, the Hymns and Epigrams from the Greek, with the Coma Berenices from the Latin of Catullus, with the original text, and notes carefully selected from former commentators, and additional observations," by H.W. Tytler, M.D.)

Callimachus Hymn to Delos 275-299

|

The legend of the Hyperborean Maidens.. So ever since [Apollo's birth], you are famed as holiest of islands, nursemaid of Apollo. Not Enyo or Hades or the horses of Ares tread upon you. But every year tithes of first fruits are sent to you. To you all cities lead choirs, those who cast their lot toward morning, those toward evening, those toward midday, and those who have their homes above the Boreal shore, a most long-lived race. They indeed first bring the stalks and holy sheaves of corn. These the Pelasgians from Dodona are much the first to receive, brought from afar, they, who sleeping on the ground, serve the never-silent cauldron. Second, the offerings arrive at the holy town and mountains of the Malian land; Thence they sail to the Abantes' good Lelantian plain, nor is it a long voyage [to Delos] from Euboea, since their harbors are your neighbors. The first to bring offerings from the blond-haired Arismaspians were Upis and Loxo and happy Hecaerge, daughters of Boreas, and men who were the best of youths. But they, not returning, never came home. Their fate, however, was a happy one, and they are never without glory, Indeed the girls of Delos, when the sweet-sounding bridal hymn agitates the girls' abodes, offer like-aged hair [for the maidens], while the boys bring their first summer harvest of cheek-down as an offering for the youths. . . |

Tower of the Winds in Athens, 1st century B.C. Representations of the Winds, including Boreas, the North Wind, encircle the tower. This structure, once surmounted by a figure of Triton as a weathervane, also included a water clock and a sundial engraved upon its walls. (Illustration from Seyffert, A Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, 1899.

Quotation for February (and the beginning of March), 2014

In honor of the Winter Olympics, we celebrate, with Pindar, the festivities around the games (they make Zeus's eagle fall asleep) |

Jupiter (the Roman Zeus), with his sceptre and eagle. The famous statue of Zeus by Phidias, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, depicted the eagle sitting on the top of the sceptre. Phidias' statue is long gone, but in this painting from Pompeii, Jupiter's eagle has hopped down and looks up eagerly, perhaps wanting to be fed. (Museo archeologico nazionale di Napoli (inv. nr. 9551), from the Casa dei Dioscuri. Image from Wikipedia.)

Winter Games and Summer Games

Snowboarding was not part of the ancient Olympic Games! The Winter Olympics have just been completed in Sochi, Russia, and the Paralympics for physically challenged athletes are about to start, also in Sochi. It is now the beginning of March, and the March Madness of college basketball will soon begin. The Quotation of the Month for February is a little late, but the Polar Vortex has given us in the Midwest and Northeast a questionable gift of deep snowdrifts and zero temperatures, and your author has spent way too much time shoveling the stuff.

Olympian, Nemean, Isthmian, and Pythian Games

It may seem odd to some that the Summer and Winter Olympics now occur in different years, but the precedent is ancient. Although the name "Olympics" alone survives in common modern parlance (and successive "Olympiads" were used by the ancient Greeks themselves for dating purposes) the Olympic Games, held not in the major city Athens but in an actual place called Olympia, were not the only great athletic festivals. Three other great Panhellenic festivals, open to all Greeks, were the Isthmian, Nemean, and Pythian, held on the years between the Olympian in constant rotation. The oldest, the Olympian, organized in 776 B.C., was held at Zeus's sanctuary at Olympia in the northern Peloponnese, the southern lobe of the Greek peninsula. The Nemean Games (founded in 573 B,C.), also honored Zeus, and were held at Nemea, also in the Peloponnese, south of Corinth. The Isthmian Games (founded in 581)were held at Poseidon's sanctuary on the Isthmus of Corinth. Nemean and Isthmian Games were held both the year before and the year after the Olympics. The Pythian, the only major games held in northern Greece, founded in 582 B.C., took place at Delphi at the sanctuary of Apollo, where he was said to have slain the dragon Pytho, where the Delphic Oracle was also situated. The Pythian Games were held in the third year of each Olympiad. They grew out of a local music festival, at which a hymn was always sung celebrating the god's victory over the monster. Music and dance contests remained a part of the Pythian Games, along with athletic and horse racing competitions.

Celebrating the celebration

Nor should we be amazed that sometimes it seems that more attention, TV coverage (and money) is spent on opening and closing ceremonies, pageantry, and entertainment than on actual sweaty bodies competing for the prizes. The great Theban poet Pindar composed some of the most glorious choral odes in the Greek language for victors in all four great Panhellenic games. They blaze with gold and splendor, though the music and dance that surrounded them are gone. Each morphs quickly into myth, with tales of gods, giants, and nymphs associated with the lineage of the winnerr. At the end we emerge to praise the glorious victor. Sweaty bodies are barely mentioned.

The eagle lulled to sleep

This month's Quotation is from the opening of Pindar's First Pythian Ode, composed for Hieron, founder of the town of Aetna in Sicily, whose entry won the chariot race in 470 B.C. Pindar begins by celebrating the lyre, which accompanies the ode and its attendant dance. Such are its golden charms that Zeus's eagle, king of birds, is lulled to sleep, his fluid back undulating to the rhythm of the performance. The fire of Zeus's thunderbolt goes out, and Ares, god of war, lays aside his weapons and falls asleep.

Here, in Greek and English, are the opening strophe and antistrophe of Pindar's First Pythian.

Pindar First Pythian 1-12

|

The eagle of Zeus is lulled to sleep

Golden lyre, joint possession of Apollo and the |

The Stadium at Delphi, where the Pythian Games were held starting in about 450 B.C.. In Pindar's time, the games were held on the plain below the mountain, and horse races were always held there. Delphi, including the stadium seen here, is perched on a shelf of land between Mount Parnassus and the deep ravine below that leads to the plain. The other buildings of the Delphic sanctuary, including the temple that was the seat of the Delphic Oracle, are located downhill from the new stadium, out of sight in this picture. (Illustration from Hanns Holdt and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, Griechenland, 1928.)

Quotation for January, 2014Happy New Year! Enjoy!

While winter storms rage, stay inside, celebrate, crack jokes, and play games (a Latin poem by Jacob Bigelow, 1808) |

A Romantic conception of a Roman banquet.

The Polar Vortex blankets the land — stock up on food and games

Once again, the Polar Vortex (or is it a wayward jet stream?) descends menacingly over North America. It sounds like something out of science fiction. Or out of Aristophanes, in whose Clouds "Socrates" explains to Strepsiades that it is not Zeus but a great "Vortex" (dinos) that causes the weather. The serious theory behind this, as opposed to Aristophanes' parody, originated with the pre-Socratic philosopher Anaxagoras (c. 500-428 B.C.), who said that elements making up the universe are separated and differentiated by a "vortex" or whirling motion.

A Latin poem from early America

This month's Quotation of the Month comes from early America. The writing of Latin verse did not end in antiquity, or even in the Middle Ages, nor was it confined to the European continent. Our Quotation is a poem published anonymously in 1808, but which has been attributed to Jacob Bigelow (1787-1879), professor of materia medica at Harvard and president of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. It appears in the collection Early American Latin Verse, admirably edited by Leo M. Kaiser (Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1984). Titled Hyems Convivio Sublevanda, it bids us relieve winter's onslaught with food, drink, and the company of friends — but skip the tobacco!

Hyems Convivio SublevandaDum ruit tectis superante nimboatra tempestas, furit atque ventus, creber et pulsis crepitat fenestris grandinis ictus, horreat nauta in pelago prehensus, horreatque expers chlamydis viator horreat, si quem foribus focisque expulit uxor. Me tamen salvo, furit imber et nix, nil nocet frigus, crepitante flamma, dumque apud mensam sedeo biboque inter amicos. Turbinis stridorem imitamur intus; cum fremit ventus, fremimus vicissim. Si fluunt imbres, fluitet Falernum amnibus aequis. Jam jocos tempusque agitare salsos, jam juvat risus stepitusque ludi; frigida et nox fit calida, atque fiunt fervidi amici. At procul sint invidia atque rixae, fumus et tetri o tabaci, mentibus ne quam noceat simultas, naribus aer. |

Alleviate Winter with ConvivialityWhile the black tempest descendsupon roofs with overwhelming storm-clouds and the wind rages, and repeated blows of hail clatter as they strike the windows, let the sailor quake when caught at sea, let the traveler quake who lacks a cloak, let the man quake, whose wife has driven him from home and hearth. But I am safe, rain and snow fall furiously, but cold does not harm me, while the fire crackles, and as long as I sit at the table and drink among friends. Inside, we imitate the whirlwind's clangor; when the wind roars, we roar in turn. If the rain flows, let Falernian wine flow forth in equal streams. Now is the time to toss about witty jokes, now laughter delights us and the din of play, the frigid night becomes warm, and friends become intense. But may envy and quarrel be far away, as well as smoke of foul tobacco, lest dissension harm our minds, or the air our noses. |

Wall painting of a banquet scene from Pompeii.

<---- Go back to first Quotations page . . . Go to Quotations for 2013 ---->

Copyright © Cora Angier Sowa. All rights reserved.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Send e-mail to Cora Angier Sowa.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Return to Minerva Systems home page.

Last Modified: